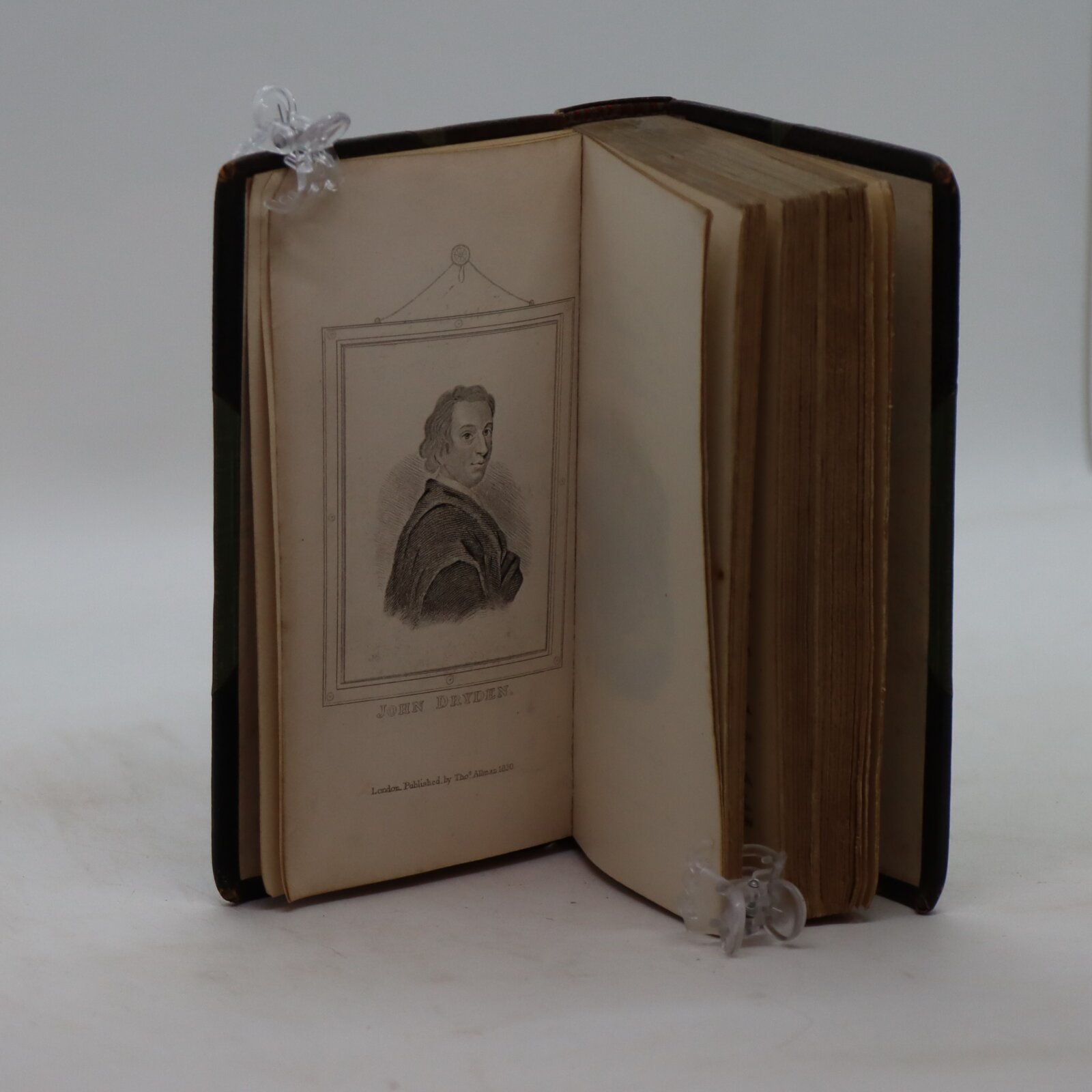

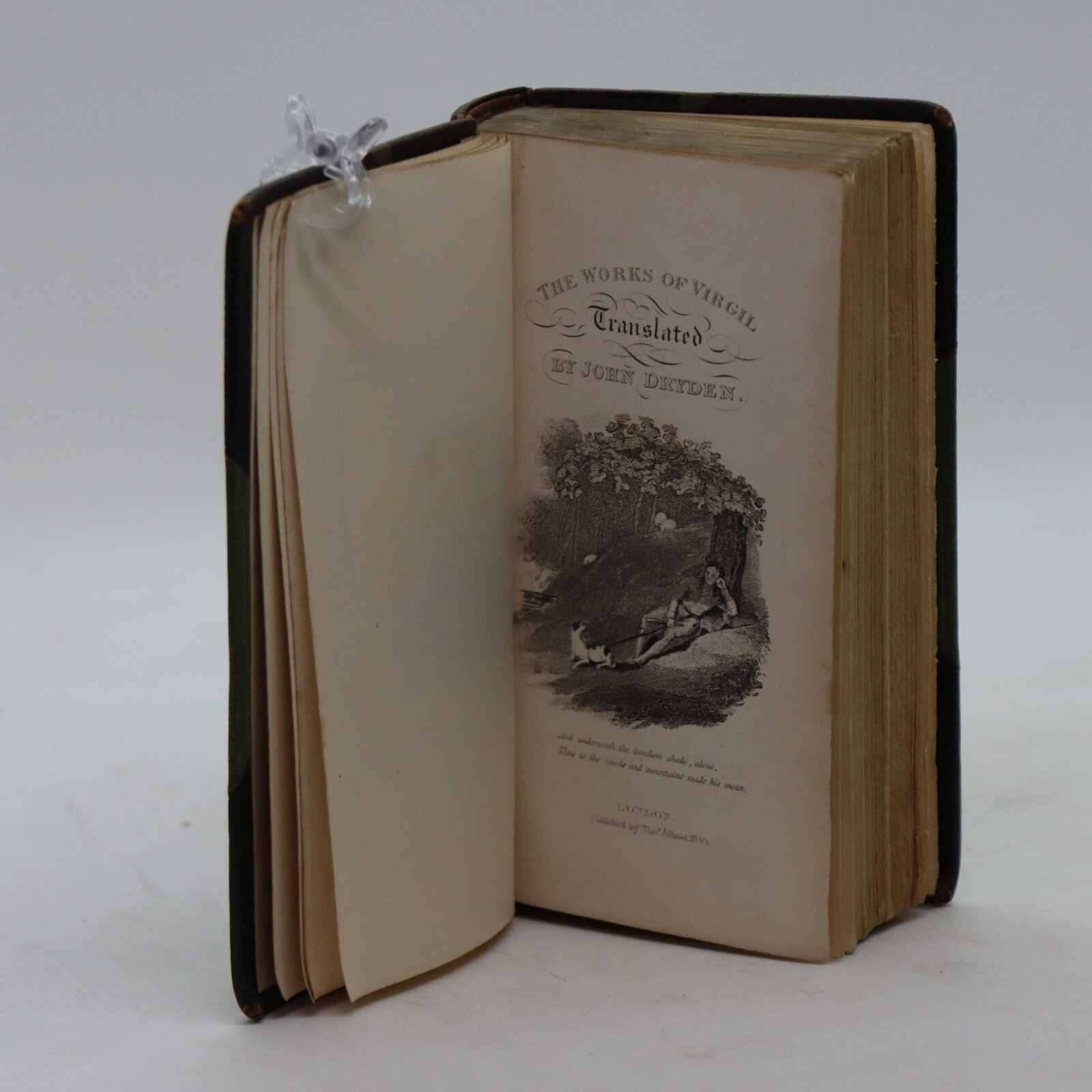

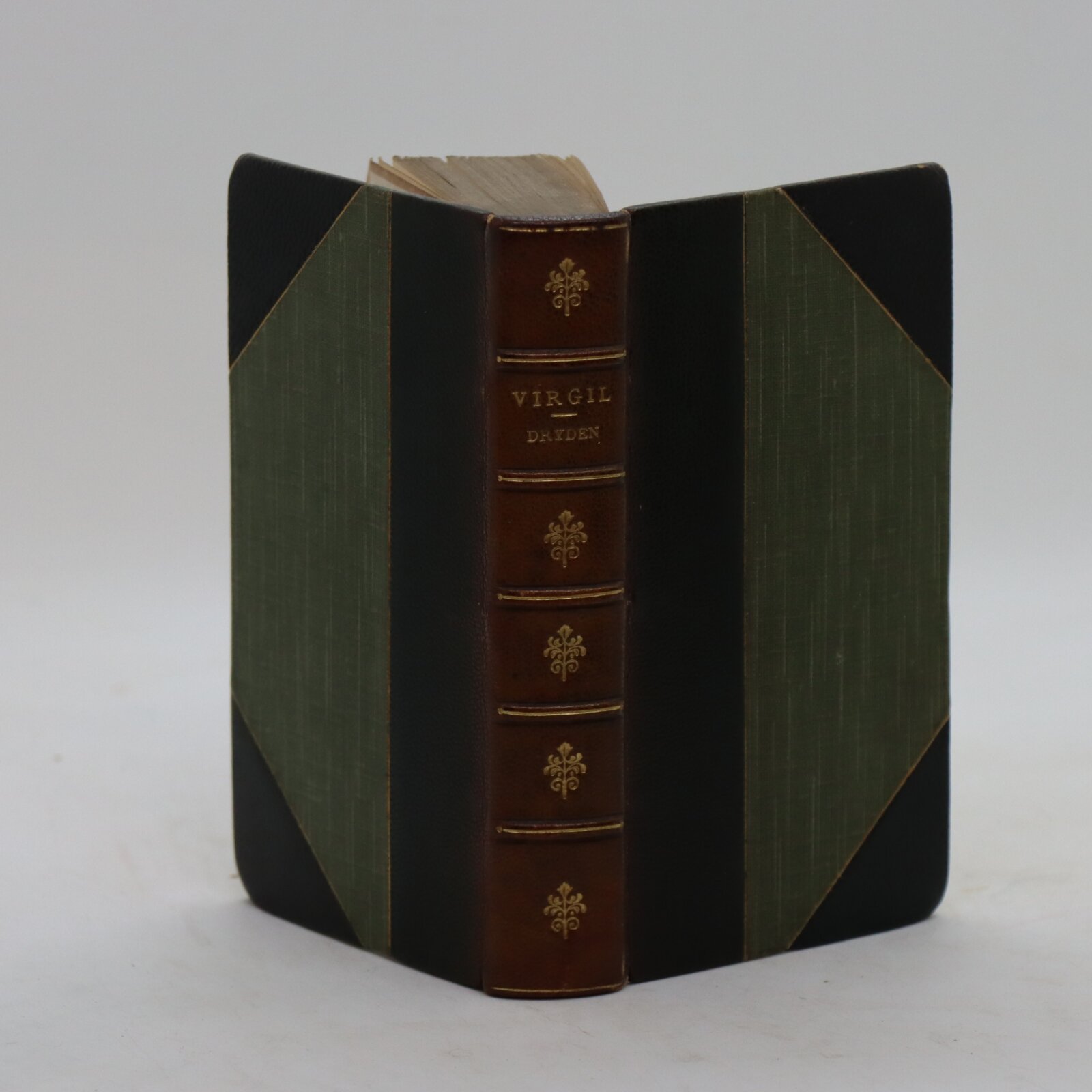

Virgil. Dryden.

By John Dryden

Printed: 1841

Publisher: Thomas Allman. London

| Dimensions | 8 × 15 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 8 x 15 x 3

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

Green calf binding with green cloth boards. Spine (faded to brown) has gilt banding and title with emblems.

A treasured early Victorian copy

Publius Vergilius Maro traditional dates 15 October 70 – 21 September 19 BC usually called Virgil or Vergil in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: the Eclogues (or Bucolics), the Georgics, and the epic Aeneid. A number of minor poems, collected in the Appendix Vergiliana, were attributed to him in ancient times, but modern scholars consider his authorship of these poems as dubious.

Virgil’s work has had wide and deep influence on Western literature, most notably Dante’s Divine Comedy, in which Virgil appears as the author’s guide through Hell and Purgatory.

Virgil has been traditionally ranked as one of Rome’s greatest poets. His Aeneid is also considered a national epic of ancient Rome, a title held since composition.

John Dryden 9 August 1631 – 1 May] 1700 was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who was appointed England’s first Poet Laureate in 1668. On 1 December 1663 Dryden married Lady Elizabeth Howard (died 1714). The marriage was at St. Swithins, London, and the consent of the parents is noted on the licence, though Lady Elizabeth was then about twenty-five. She was the object of some scandals, well or ill founded; it was said that Dryden had been bullied into the marriage by her playwright brothers. A small estate in Wiltshire was settled upon them by her father. The lady’s intellect and temper were apparently not good; her husband was treated as an inferior by those of her social status. Both Dryden and his wife were warmly attached to their children. They had three sons: Charles (1666–1704), John (1668–1701), and Erasmus Henry (1669–1710). Lady Elizabeth Dryden survived her husband but went insane soon after his death. Though some have historically claimed to be from the lineage of John Dryden, his three children had no children themselves.

Dryden is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden. Romanticist writer Sir Walter Scott called him “Glorious John”.

What Dryden achieved in his poetry was neither the emotional excitement of the early nineteenth-century romantics nor the intellectual complexities of the metaphysicals. His subject matter was often factual, and he aimed at expressing his thoughts in the most precise and concentrated manner. Although he uses formal structures such as heroic couplets, he tried to recreate the natural rhythm of speech, and he knew that different subjects need different kinds of verse. In his preface to Religio Laici he says that “the expressions of a poem designed purely for instruction ought to be plain and natural, yet majestic… The florid, elevated and figurative way is for the passions; for (these) are begotten in the soul by showing the objects out of their true proportion…. A man is to be cheated into passion, but to be reasoned into truth.”

Translation style

While Dryden had many admirers, he also had his share of critics, Mark Van Doren among them. Van Doren complained that in translating Virgil’s Aeneid, Dryden had added “a fund of phrases with which he could expand any passage that seemed to him curt.” Dryden did not feel such expansion was a fault, arguing that as Latin is a naturally concise language it cannot be duly represented by a comparable number of words in English. “He…recognized that Virgil ‘had the advantage of a language wherein much may be comprehended in a little space’ (5:329–30). The ‘way to please the best Judges…is not to Translate a Poet literally; and Virgil least of any other’ (5:329).”

For example, take lines 789–795 of Book 2 when Aeneas sees and receives a message from the ghost of his wife, Creusa.

iamque vale et nati serva communis amorem.’

haec ubi dicta dedit, lacrimantem et multa volentem

dicere deseruit, tenuisque recessit in auras.

ter conatus ibi collo dare bracchia circum;

ter frustra comprensa manus effugit imago,

par levibus ventis volucrique simillima somno.

sic demum socios consumpta nocte reviso

Dryden translates it like this:

I trust our common issue to your care.’

She said, and gliding pass’d unseen in air.

I strove to speak: but horror tied my tongue;

And thrice about her neck my arms I flung,

And, thrice deceiv’d, on vain embraces hung.

Light as an empty dream at break of day,

Or as a blast of wind, she rush’d away.

Thus having pass’d the night in fruitless pain,

I to my longing friends return again

Dryden’s translation is based on presumed authorial intent and smooth English. In line 790 the literal translation of haec ubi dicta dedit is “when she gave these words.” But “she said” gets the point across, uses half the words, and makes for better English. A few lines later, with ter conatus ibi collo dare bracchia circum; ter frustra comprensa manus effugit imago, he alters the literal translation “Thrice trying to give arms around her neck; thrice the image grasped in vain fled the hands,” in order to fit it into the metre and the emotion of the scene.

In his own words,

The way I have taken, is not so streight as Metaphrase, nor so loose as Paraphrase: Some things too I have omitted, and sometimes added of my own. Yet the omissions I hope, are but of Circumstances, and such as wou’d have no grace in English; and the Addition, I also hope, are easily deduc’d from Virgil’s Sense. They will seem (at least I have the Vanity to think so), not struck into him, but growing out of him. (5:529)

In a similar vein, Dryden writes in his Preface to the translation anthology Sylvae:

Where I have taken away some of [the original authors’] Expressions, and cut them shorter, it may possibly be on this consideration, that what was beautiful in the Greek or Latin, would not appear so shining in the English; and where I have enlarg’d them, I desire the false Criticks would not always think that those thoughts are wholly mine, but that either they are secretly in the Poet, or may be fairly deduc’d from him; or at least, if both those considerations should fail, that my own is of a piece with his, and that if he were living, and an Englishman, they are such as he wou’d probably have written.

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend