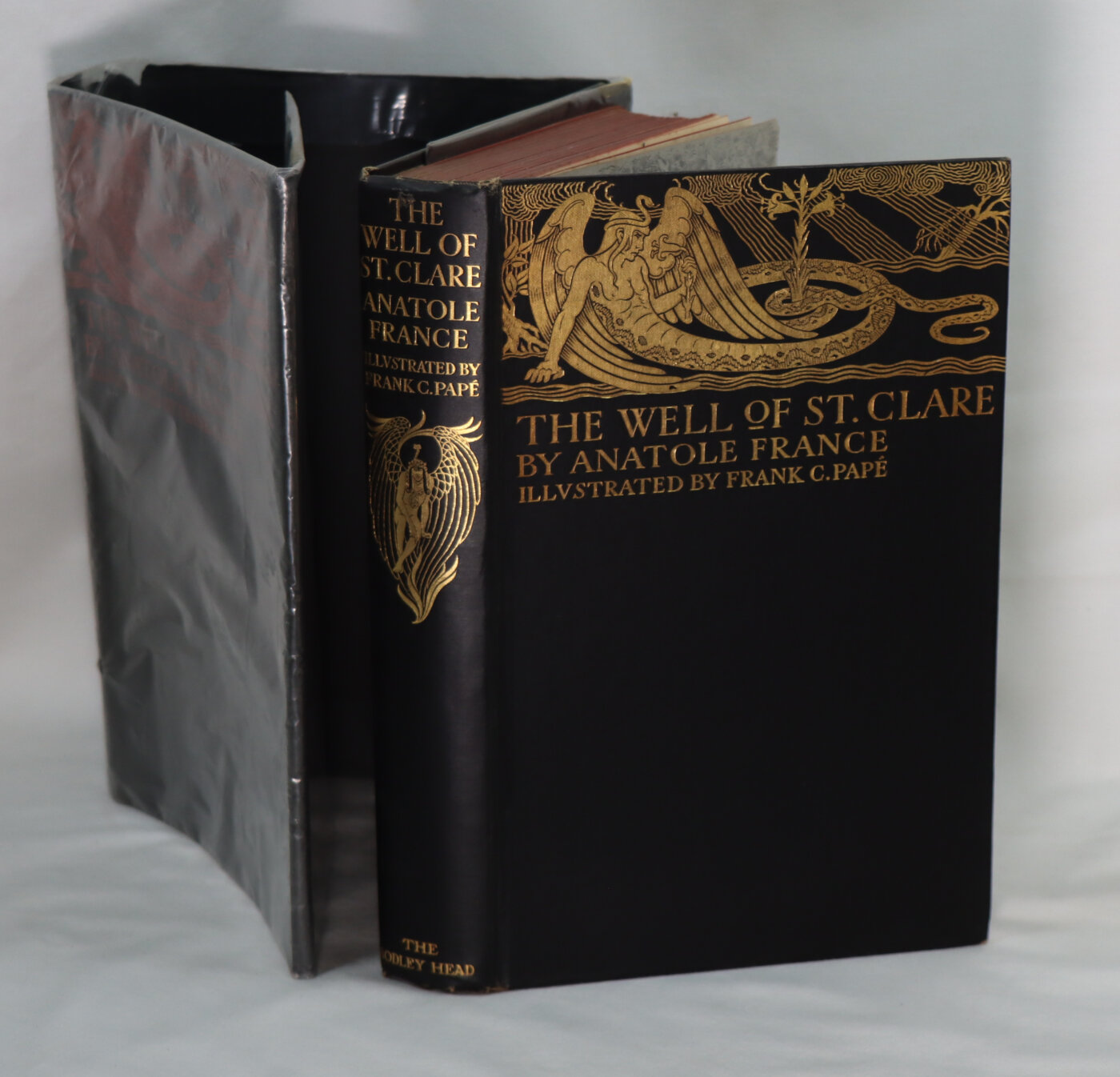

The Well of St Clare.

By Anatole France

Printed: 1958

Publisher: The Bodley Head. London

Edition: Illustrated edition

| Dimensions | 17 × 25 × 4 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 17 x 25 x 4

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

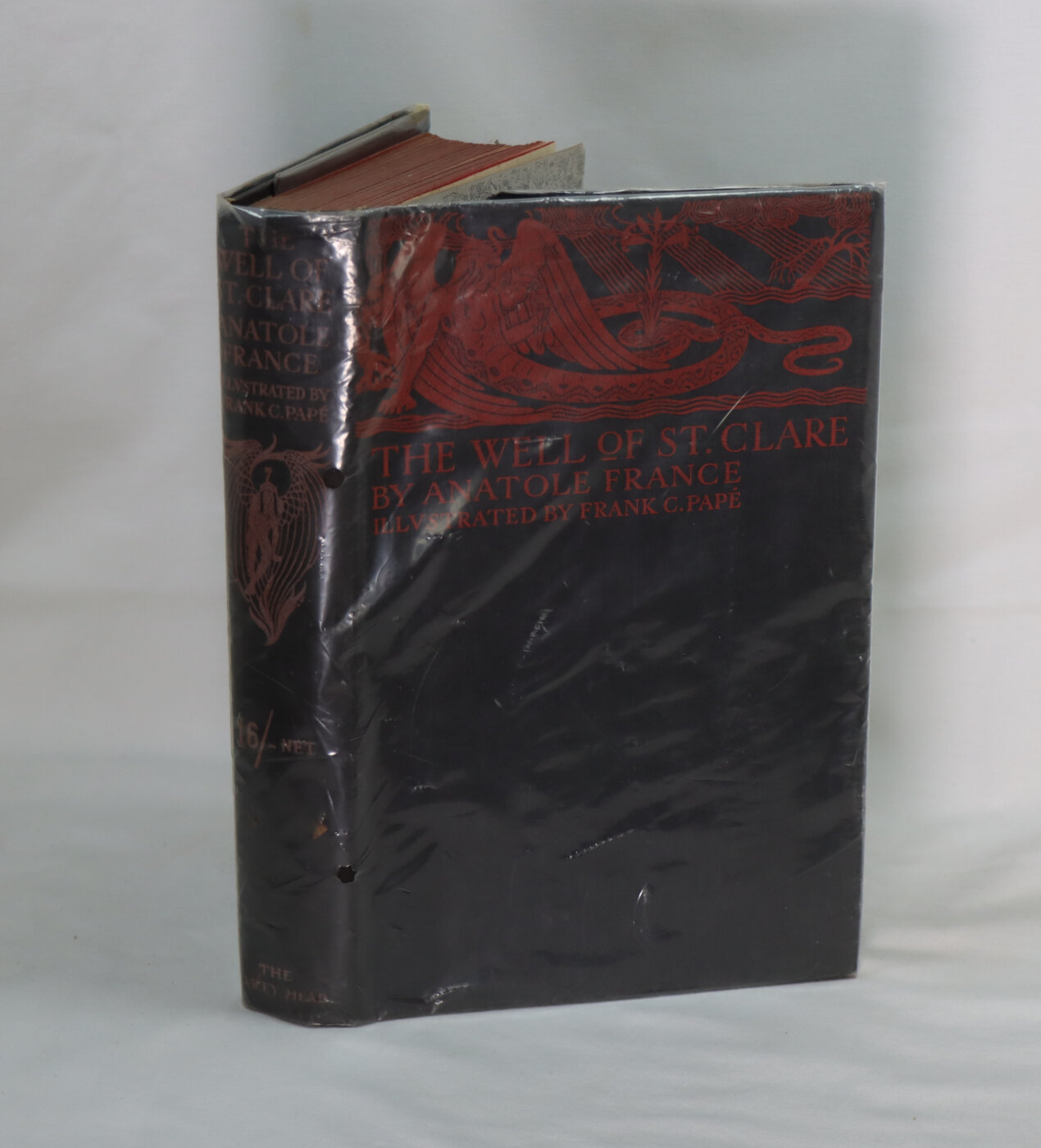

In the original dust cover (with an extra clear cover). Black cloth binding with gilt title and decoration on the spine and front board.

-

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

-

Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list.

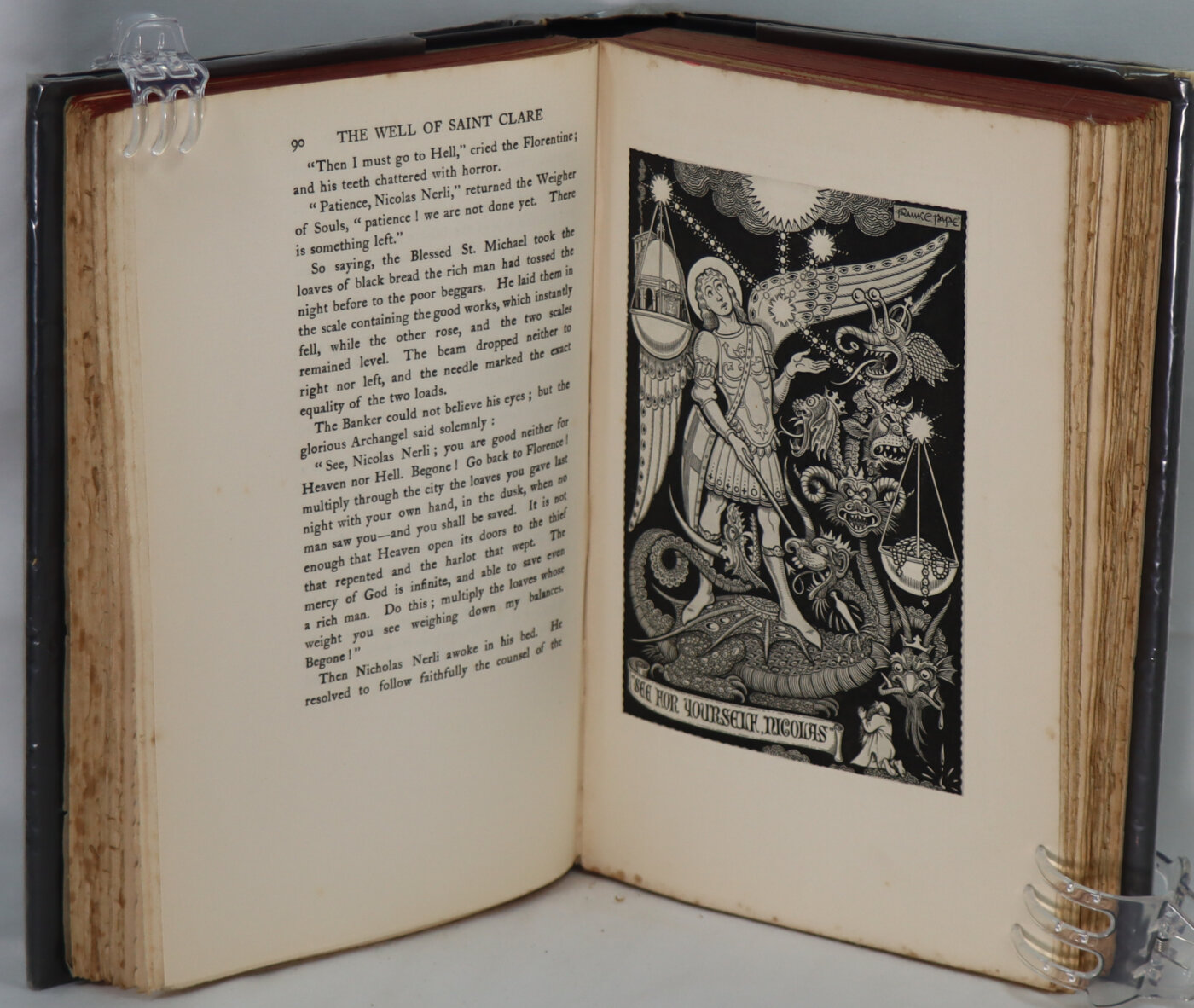

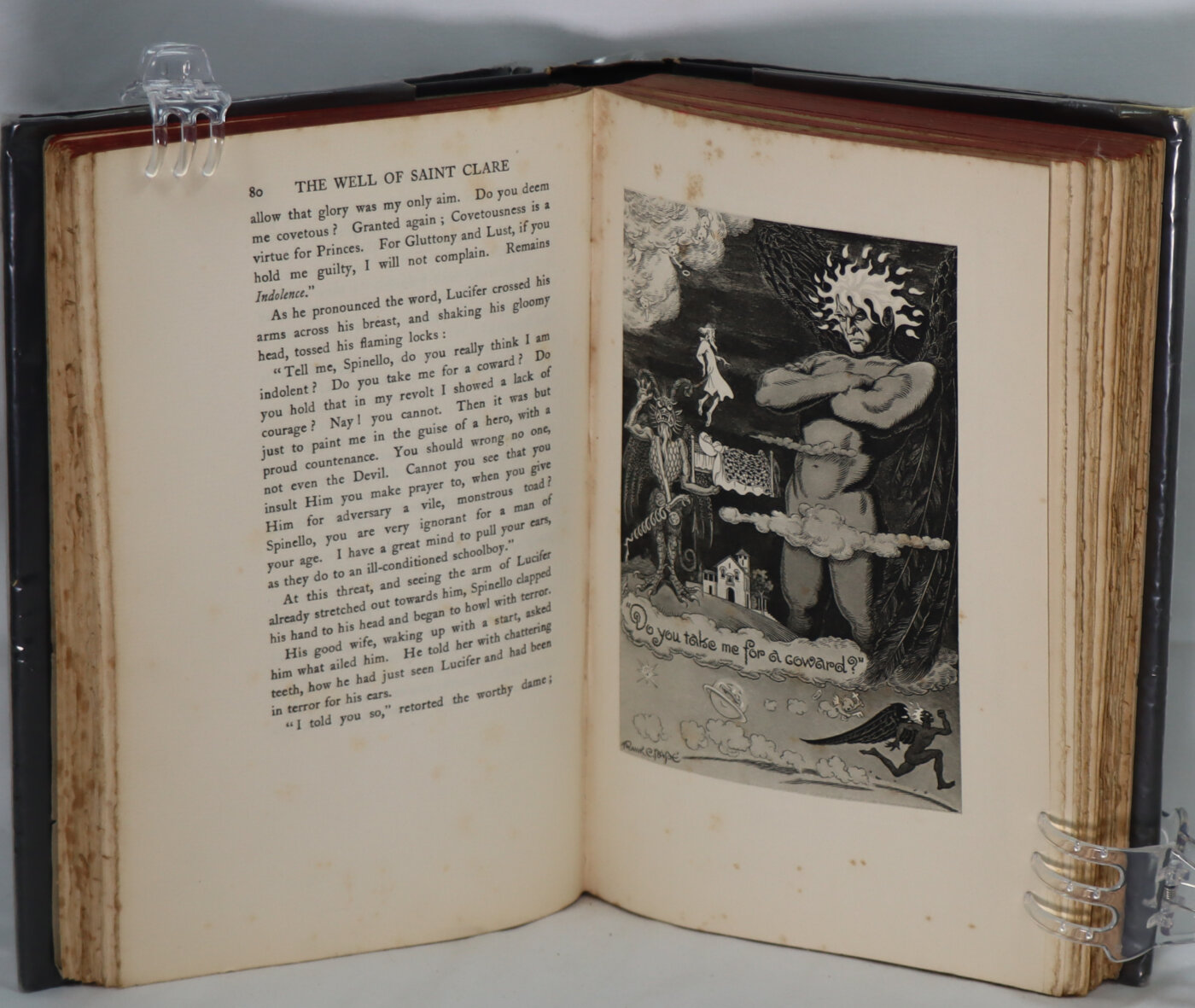

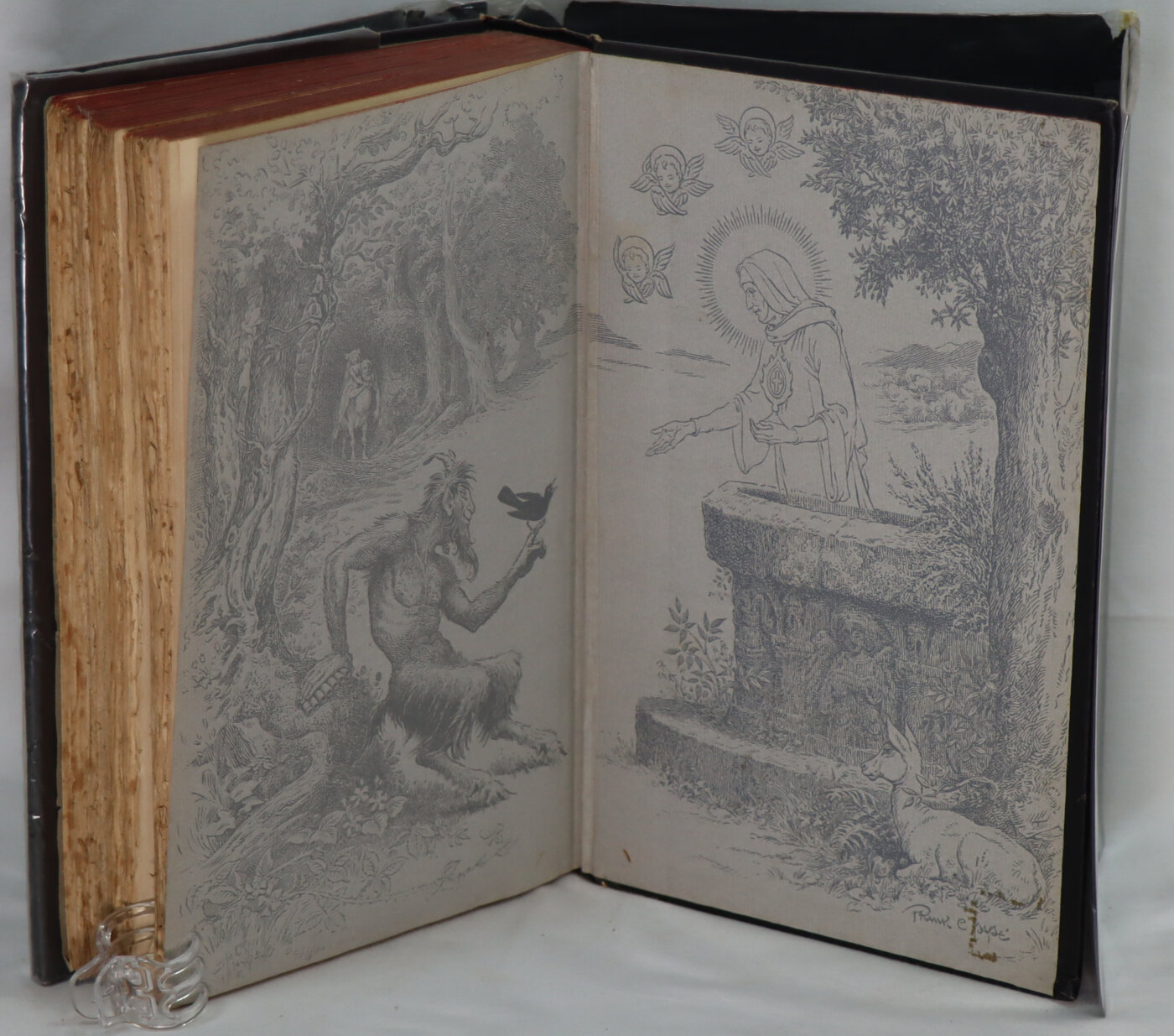

First Edition (Illustrated). Illustrated with decorations and twelve full-page black-and-white drawings by Frank C. PAPE; decorated endpapers. This work has been reissued many times in many formats, but nothing compares with owning a copy in an early original state. More images and/or description can be sent on request.

——————

The irony of Anatole France when he writes about Christianity is always tempered by a respect for its cultural importance. He sends it up but by putting it in a larger context of European myth and legend. France’s target is not Christian culture but the Christian clericalism that uses that culture to promote itself. Christian belief, for him, is in a continuous line of artistic development from ancient Greece to the late nineteenth century. This makes it an object of critical admiration rather than derision.

The Well of St. Clare is a jewel of ironic praise for Christianity. The narrator’s narrator, the Reverend Father Adone Doni, is an eccentric Franciscan friar who puts his faith in the Spirit but not in the hierarchy of the Church. He tells stories of the medieval Church while sitting in the evening by the abandoned well associated with the Franciscan St. Clare. His stories are not of Christian superiority but of Christian continuity with that which existed before anyone had ever heard of “the Galilean.”

The initial tale of the Tomb of San Satori sets the scene. The occupant of that place of veneration is not a Christian martyr, or doer of good works. He is an ancient satyr, the last of his kind, who existed on not unfriendly terms with the original Christian immigrants to the region of Sienna who had driven away the native nymphs associated originary creatures. Like so much else, the satyr was gradually assimilated into the Christian cult. For him the transition from the Age of Jupiter, to the Age of Saturn, to the Age of the Galilean is simply history, not a movement toward some better or even different world. So despite his questionable genetic and moral status, he has morphed into a Christian sage.

Ghosts are commonplace in the stories of Father Adone. They are the carriers of culture as they appear in dreams and apparitions. So the ghost of a young Roman girl, Julia Læta, appears in the Florentine Guido Cavalcanti’s story. Julia is buried in a tomb which pre-dates the establishment of the church of which her graveyard forms a part. She is effectively a member of the Community of Saints which includes those dead long before the advent of Christianity. Guido’s ambition after dreaming about her is to join her pre-Christian band.

The story of Spinello of Arrezo is an account of why culture is the matrix of religion, not the other way round. As an artist, it is Spinello who interprets religious doctrine to the masses in a way that was far more powerful than any preacher or academic theologian. Once again it is through a dream that Spinello is informed about the truth of Lucifer, the fallen angel and traditional source of all evil. The Angel of Darkness has been unfairly maligned through bad portraiture, he discovers. An injustice has been done to the one who has been tagged as the source of injustice. The truth kills the poor man.

On the surface, the story of Nicholas Nerli is somewhat different. Nicholas, a devious and corrupt businessman, maintains his good name by patronage and benefactions. But his spiritual salvation, made apparent in a dream of his death, is assured by the relatively inexpensive distribution of bread to the poor. The apparent moral: If you’re going to be a crook, at least be an efficient one. The message applies implicitly as well to one’s discretionary spending: Ensure that it goes to what is culturally significant and applied with good taste. Mere money is inadequate for the cause.

Many other stories are built around the art or artistic techniques of ancient Greece and their use in Italian churches – tesseræ of molten glass, impastos, and mosaics for example. It is the artists, sculptors, writers, and men (and some women) of taste who are the ones who make religion palatable, understandable, and respectable. They work for the Church because the Church has the money, either from its own coffers or those of its benefactors. But the artistic inspiration and traditions are classical in origin, and consequently pagan. Artistry, therefore, slowly but persistently alters the substance of Christianity.

From the tone of the Reverend Father Adone, such an evolution of Christianity is not a bad thing. His approving view of the medieval church is that it was healthily cosmopolitain, inevitably so given the taste and intellect of those who ran it. Ultimately it is art – with its intellect, historical sensitivity, and creative skill – which leads the Church in a sort of continuous renovation. The fact that the Church sees things the other way round is an innocent conceit which is easily tolerated.

Irony, of course, is most delicious when served without heavy sauces or seasonings. France is a master of the light ironic touch, its chef de cuisine one might say.

Anatole France (born François-Anatole Thibault, 16 April 1844 – 12 October 1924) was a French poet, journalist, and novelist with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters. He was a member of the Académie Française, and won the 1921 Nobel Prize in Literature “in recognition of his brilliant literary achievements, characterized as they are by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament”. France is also widely believed to be the model for narrator Marcel’s literary idol Bergotte in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time.

The son of a bookseller, France, a bibliophile, spent most of his life around books. His father’s bookstore specialized in books and papers on the French Revolution and was frequented by many writers and scholars. France studied at the Collège Stanislas, a private Catholic school, and after graduation he helped his father by working in his bookstore. After several years, he secured the position of cataloguer at Bacheline-Deflorenne and at Lemerre. In 1876, he was appointed librarian for the French Senate.

France began his literary career as a poet and a journalist. In 1869, Le Parnasse contemporain published one of his poems, “La Part de Madeleine”. In 1875, he sat on the committee in charge of the third Parnasse contemporain compilation. As a journalist, from 1867, he wrote many articles and notices. He became known with the novel Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard (1881). Its protagonist, skeptical old scholar Sylvester Bonnard, embodied France’s own personality. The novel was praised for its elegant prose and won him a prize from the Académie Française.

In La Rotisserie de la Reine Pedauque (1893) France ridiculed belief in the occult, and in Les Opinions de Jérôme Coignard (1893), France captured the atmosphere of the fin de siècle. He was elected to the Académie Française in 1896.

France took a part in the Dreyfus affair. He signed Émile Zola’s manifesto supporting Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer who had been falsely convicted of espionage. France wrote about the affair in his 1901 novel Monsieur Bergeret.

France’s later works include Penguin Island (L’Île des Pingouins, 1908) which satirizes human nature by depicting the transformation of penguins into humans – after the birds have been baptized by mistake by the almost-blind Abbot Mael. It is a satirical history of France, starting in Medieval times, going on to the author’s own time with special attention to the Dreyfus affair and concluding with a dystopian future. The Gods Are Athirst (Les dieux ont soif, 1912) is a novel, set in Paris during the French Revolution, about a true-believing follower of Maximilien Robespierre and his contribution to the bloody events of the Reign of Terror of 1793–94. It is a wake-up call against political and ideological fanaticism and explores various other philosophical approaches to the events of the time. The Revolt of the Angels (La Revolte des Anges, 1914) is often considered France’s most profound and ironic novel. Loosely based on the Christian understanding of the War in Heaven, it tells the story of Arcade, the guardian angel of Maurice d’Esparvieu. Bored because Bishop d’Esparvieu is sinless, Arcade begins reading the bishop’s books on theology and becomes an atheist. He moves to Paris, meets a woman, falls in love, and loses his virginity causing his wings to fall off, joins the revolutionary movement of fallen angels, and meets the Devil, who realizes that if he overthrew God, he would become just like God. Arcade realizes that replacing God with another is meaningless unless “in ourselves and in ourselves alone we attack and destroy Ialdabaoth.” “Ialdabaoth”, according to France, is God’s secret name and means “the child who wanders”.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921. He died on 13 October 1924 and is buried in the Neuilly-sur-Seine Old Communal Cemetery near Paris.

On 31 May 1922, France’s entire works were put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (“List of Prohibited Books”) of the Catholic Church. He regarded this as a “distinction”. This Index was abolished in 1966.

Personal life: In 1877, France married Valérie Guérin de Sauville, a granddaughter of Jean-Urbain Guérin, a miniaturist who painted Louis XVI. Their daughter Suzanne was born in 1881 (and died in 1918).

France’s relations with women were always turbulent, and in 1888 he began a relationship with Madame Arman de Caillavet, who conducted a celebrated literary salon of the Third Republic. The affair lasted until shortly before her death in 1910.

After his divorce, in 1893, France had many liaisons, notably with a Madame Gagey, who committed suicide in 1911.

In 1920, France married for the second time, to Emma Laprévotte.

France had socialist sympathies and was an outspoken supporter of the 1917 Russian Revolution. However he also vocally defended the institution of monarchy as more inclined to peace than bourgeois democracy, saying in relation to efforts to end the First World War that “a king of France, yes a king, would have had pity on our poor, exhausted, bloodied nation. However democracy is without a heart and without entrails. When serving the powers of money, it is pitiless and inhuman.” In 1920, he gave his support to the newly founded French Communist Party. In his book The Red Lily, France famously wrote, “The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal loaves of bread.”

Reputation: The English writer George Orwell defended France and declared that his work remained very readable, and that “it is unquestionable that he was attacked partly from political motives”.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend