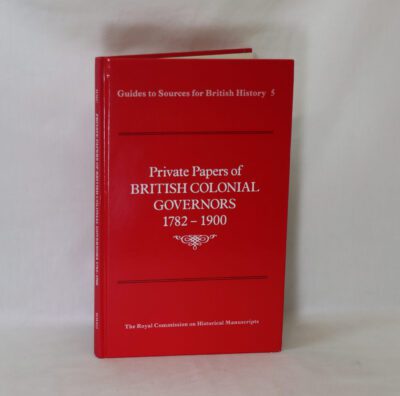

The Mind in the Cave.

By David Lewis-Williams

ISBN: 9780500770443

Printed: 2012

Publisher: Thames & Hudson. London

Edition: Reprint

| Dimensions | 16 × 24 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 16 x 24 x 3

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

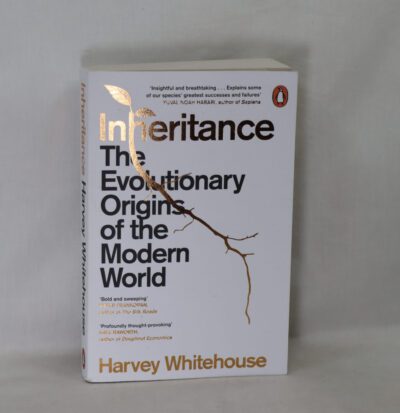

Softback. Brown spine with white title. Buffalo cave drawing on the front board.

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feel and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art is a 2002 study of Upper Palaeolithic European rock art written by the archaeologist David Lewis-Williams, then a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lewis-Williams opens The Mind in the Cave with a preface, in which he outlines the methodology that he is working with, and emphasises his position that “we do not have to explain everything to explain something”, what he calls “Three Caves: Three Time-Bytes”, brief page-long narratives set in the Upper Palaeolithic sites of the Volp Caves, the Niaux Cave and Chauvet Cave. In the first chapter, entitled "Discovering Human Antiquity", Lewis-Williams explores the early

scholarly understanding of Upper Palaeolithic art, stemming from the increased interest in the origins of the human species sparked by the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. He proceeds to discuss early attempts to analyse both portable and parietal art, and the early belief that cave paintings were forgeries, being too sophisticated to have been produced by “primitive” humans, before scholars eventually came to accept their authenticity. Finally, he notes the developments in radiocarbon dating, which enabled far more accurate dating of archaeological sites, allowing scholars to appreciate the exact antiquity of the Upper Palaeolithic. Chapter two, “Seeking Answers”, proceeds to examine the various different interpretative approaches that scholars have taken to the Upper Palaeolithic cave art of Europe. Noting the problems innate with using the term “art”, he nevertheless believes it can still be used in this context with caution. From there, he looks at the early claims that rejected symbolic-religious explanations, instead adopting an “art for art’s sake” approach, and then its fall from academic credibility. He then discusses the claims that the artworks did have symbolic meanings, being either totemic or representative of sympathetic magic, both arguments made from ethnographic parallels with modern hunter-gatherer communities such as those of Australia. Lewis-Williams goes on to discuss structuralist interpretations of the artworks, such as those first advocated by Giambattista Vico and Ferdinand de Saussure, and later reformulated by the likes of Max Raphael, Annette Laming-Emperaire and André Leroi-Gourhan.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend