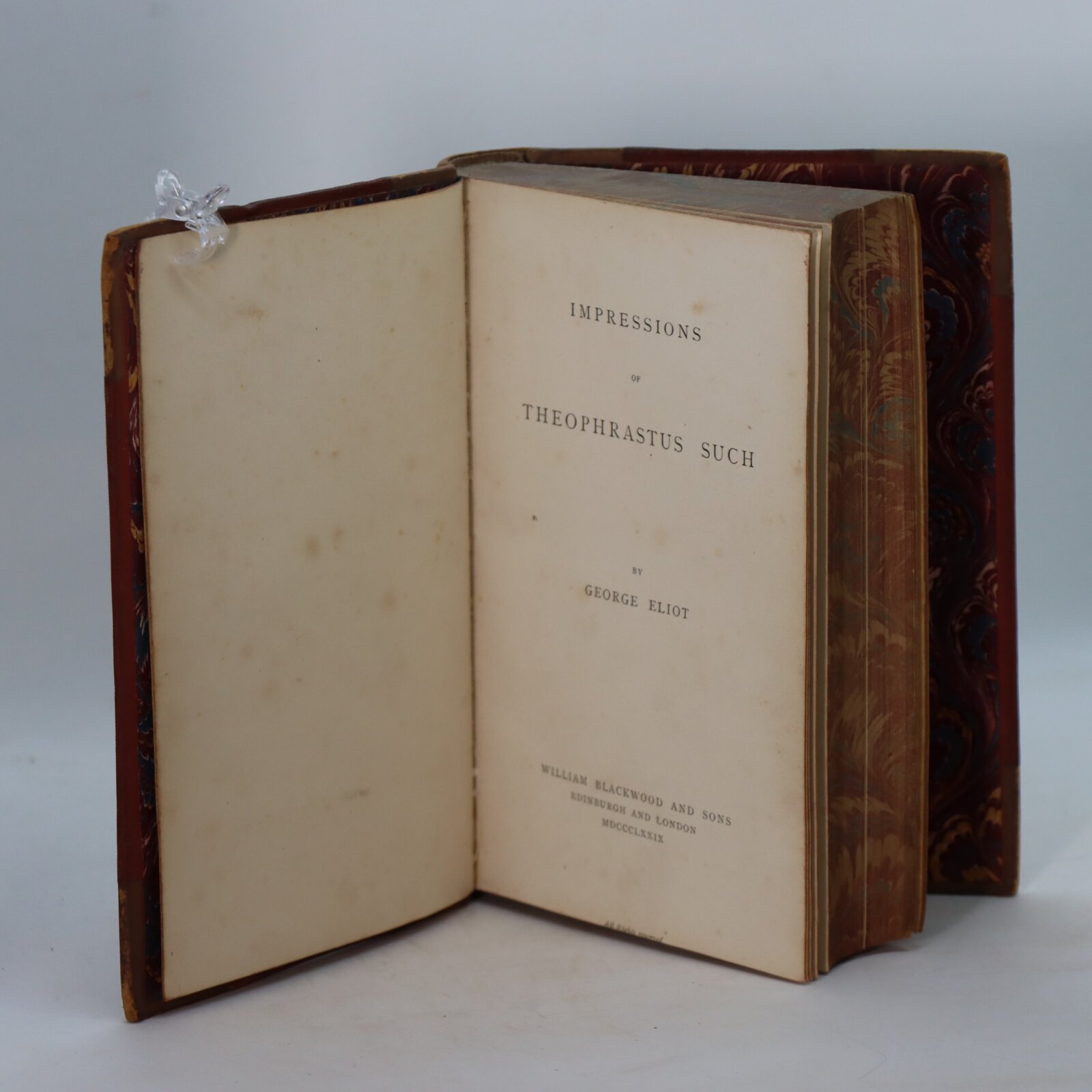

Impressions of Theophrastus Such.

By George Eliot

Printed: 1879

Publisher: William Blackwood. London

Edition: first edition

| Dimensions | 14 × 20 × 3.5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 14 x 20 x 3.5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

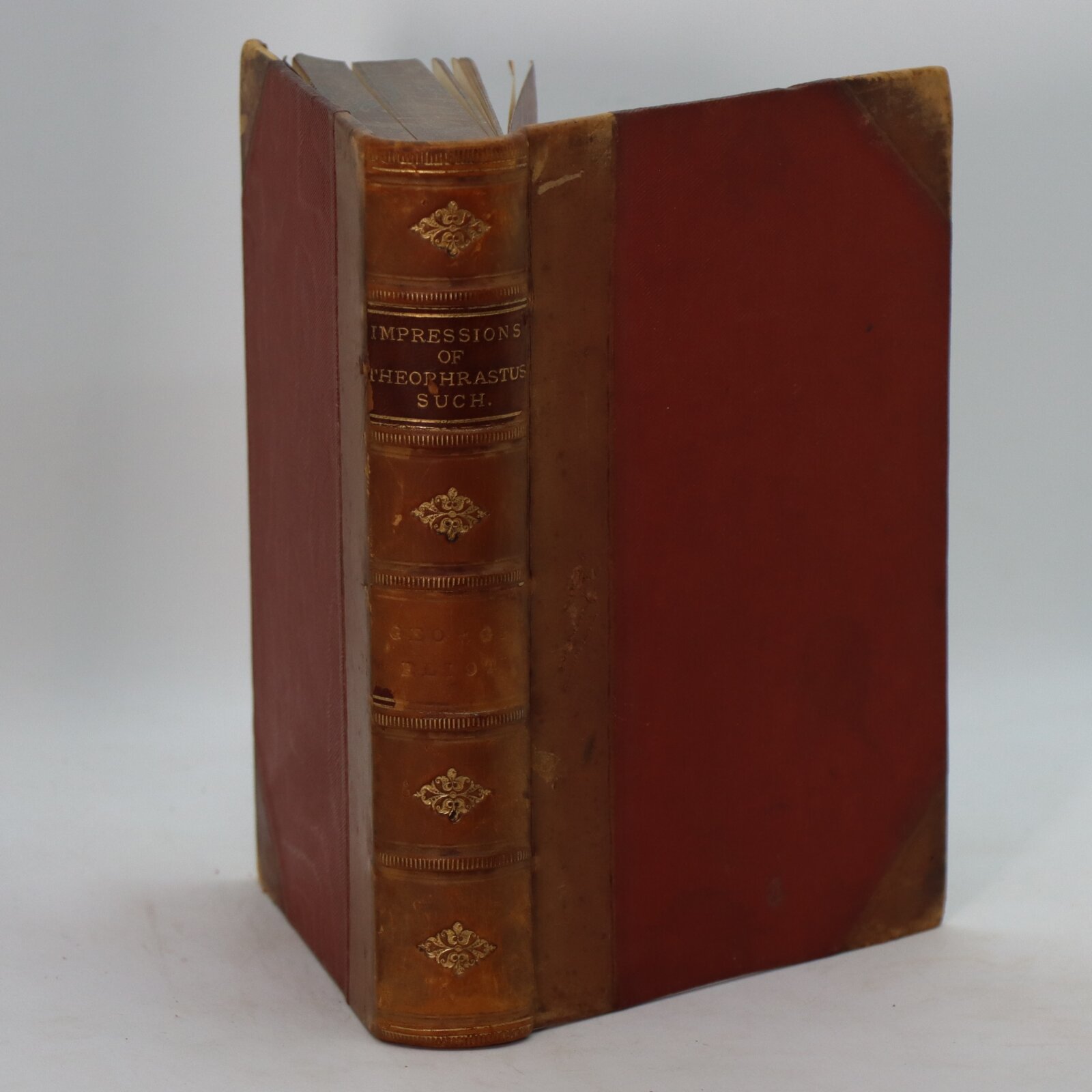

Tan half binding with red cloth boards. Brown title plate with gilt lettering, banding and emblems.

It is the intent of F.B.A. to provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this book offered so to almost stimulate your feel and touch on the book. If requested, more traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

First Edition

Impressions of Theophrastus Such is a work of fiction by George Eliot (Marian Evans), first published in 1879. It was Eliot’s last published writing and her most experimental, taking the form of a series of literary essays by an imaginary minor scholar whose eccentric character is revealed through his work. In a series of eighteen sometimes satirical character studies, Theophrastus Such focuses on various types of people he has observed in society. Usually, Theophrastus Such acts as a first-person narrator, but at several points, the voice of Theophrastus Such is lost or becomes confused with Eliot’s omniscient perspective. Some readers have identified biographical similarities between Eliot herself and the upbringing and temperament Theophrastus Such claims as his own. In her letters, George Eliot describes herself using many of the same terms.

At the time of Impressions of Theophrastus Such’s publication, the audience of George Eliot had not been expecting another work from the authoress’ pen until she had finished her late husband’s (George Henry Lewes) literary project. Though many reviews expressed their initial excitement for the book, they also expressed their disappointment. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph compared the work to “those numerous preliminary sketches which a painter makes in the course of elaborating a great picture.” The Chicago Daily Tribune likewise saw Impressions of Theophrastus Such as the possible groundwork for another of George Eliot’s novels, never to be fully realized. This reviewer notes the similarities between the essays in Impressions of Theophrastus Such with excerpts scattered throughout George Eliot’s works. Many of the reviews acknowledge the writing within Impressions of Theophrastus Such to be clever but its long-windedness and inability to evoke an emotional response renders little enjoyment for the readers. The London Echo, The Standard, and The Pall Mall Gazette comment upon the last chapter of Impressions of Theophrastus Such (Ch. XVIII “The Modern Hep! Hep! Hep!), discussing George Eliot’s novel Daniel Deronda and how the authoress presents Jews within her works. The Pall Mall Gazette believed this chapter to be the only section harkening back to the skill and style displayed in George Eliot’s celebrated works. The Standard believed Theophrastus Such showed a brilliance in its satirical and humorous hints but lacked depth, giving off an ephemeral air and distancing readers from the book’s characters.

Impressions of Theophrastus Such is not one of George Eliot’s most studied works, many researchers focus on her novels, but there have been a few essays discussing the significance and symbolism contained within the series of literary essays.

Emily Butler-Probst’s essay, “They Read with Their Own Eye from Nature’s Own Book: Imagining Whales in Impressions of Theophrastus Such” (2021), focuses on the chapter concerning Proteus Merman (Ch. III “How We Encourage Research”), where a group of academics refuse to acknowledge Merman’s theories because he is not one of them. Butler-Probst builds on many of the connections between George Henry Lewes and Proteus Merman from Dr. Beverley Park Rilett’s 2016 article “George Henry Lewes, the Real Man of Science Behind George Eliot’s Fictional Pedants,” which is referenced in the summary on Ch. III, though Butler-Probst’s article goes on to highlight Lewes’s influences beyond character inspiration to include Eliot’s allusions to Lewes’s Seaside Studies content.

Scott C. Thompson, in his 2018 essay, “Subjective Realism and Diligent Imagination: G.H. Lewes’s Theory of Psychology and George Eliot’s Impressions of Theophrastus Such,” speaks of the progression of George Eliot’s realism in her novels, from the perceptive observations in her early works to the complex social groups built into her later writings. Though it does have a cast of characters acting out scenes and exchanging dialogue, Impression of Theophrastus Such does not tell a story, as did her novels. Thompson especially points out George Eliot’s deviation in her decision to write her last work in first-person rather than the third-person narrator of her novels and how this changed her usual characters from “fully realized and psychologically complex” to “typified [and] one-dimensional”.

Another recent article, “George Eliot’s Last Stand: Impressions of Theophrastus Such” (2016) by Rosemarie Bodenheimer explores how contemporary readers felt about the change in style, and explores whether Impressions of Theophrastus Such is meant to be read as a fictional narrative fiction. She also delineates the significance and views of Theophrastus Such as the narrator. According to Bodenheimer, readers felt betrayed by the change of tune in George Eliot’s works; along with several other recent scholars, Bodenheimer argues for reading Impressions of Theophrastus Such as a work of fiction, noting that Theophrastus is a “self-reflexive fictional character whose failings and contradictions are the real subject of the book”. The book was written in the form of reflexive essays, but it is still fiction because the people and events Theophrastus Such observes are imagined.

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrote seven novels: Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1862–63), Felix Holt, the Radical (1866), Middlemarch (1871–72) and Daniel Deronda (1876). Like Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, she emerged from provincial England; most of her works are set there. She is known for their realism, psychological insight, sense of place and detailed depiction of the countryside.

Although female authors were published under their own names during her lifetime, she wanted to escape the stereotype of women’s writing being limited to lighthearted romances or other lighter fare not to be taken very seriously. She also wanted to have her fiction judged separately from her already extensive and widely known work as a translator, editor, and critic. Another factor in her use of a pen name may have been a desire to shield her private life from public scrutiny, thus avoiding the scandal that would have arisen because of her relationship with the married George Henry Lewes.

Middlemarch was described by the novelist Virginia Woolf as “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people” and by Martin Amis and Julian Barnes as the greatest novel in the English language.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend