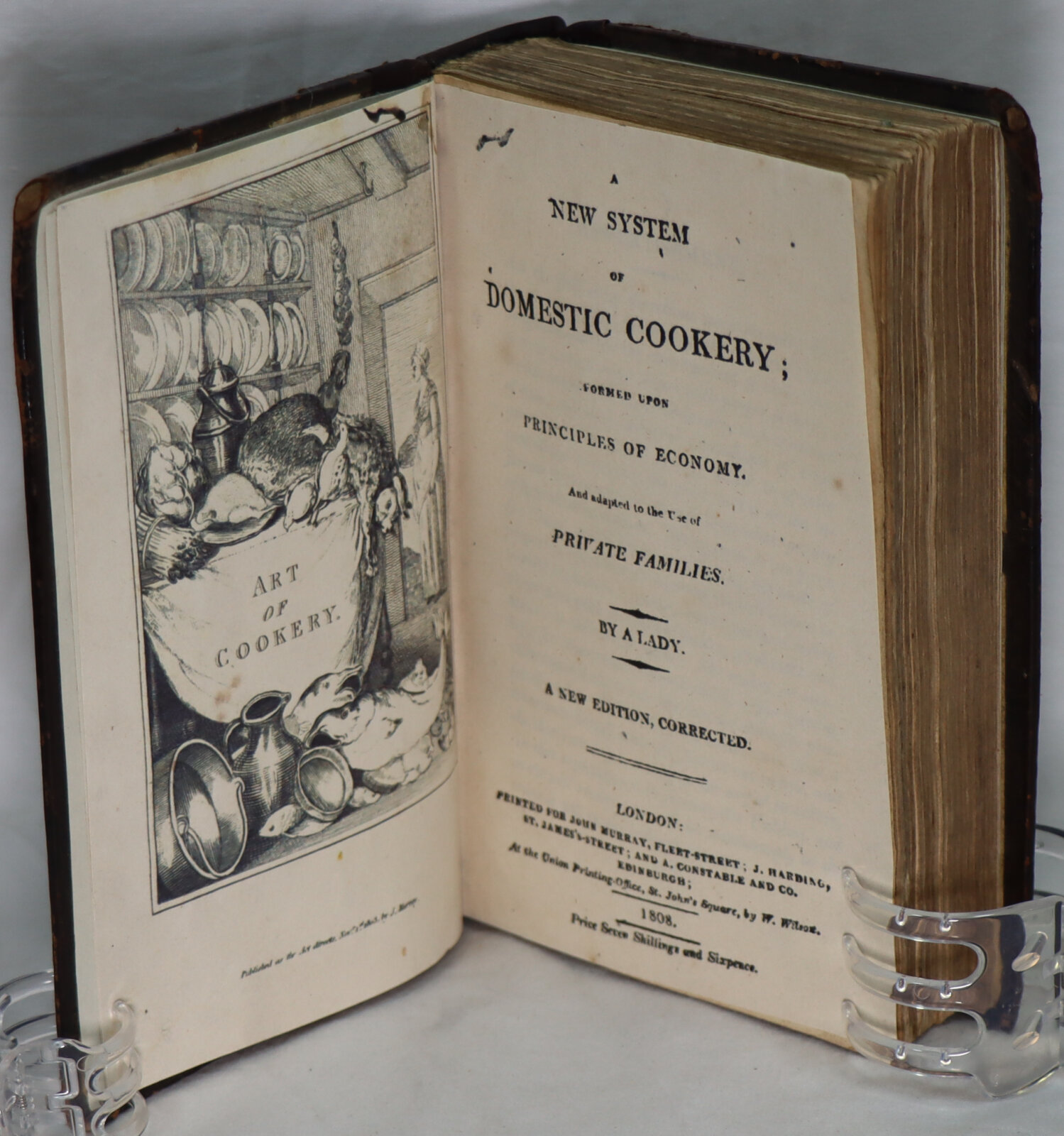

Domestic Cookery.

By Maria Rundell

Printed: 1808

Publisher: John Murray. London

Edition: New edition, corrected

| Dimensions | 11 × 16 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 11 x 16 x 3

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

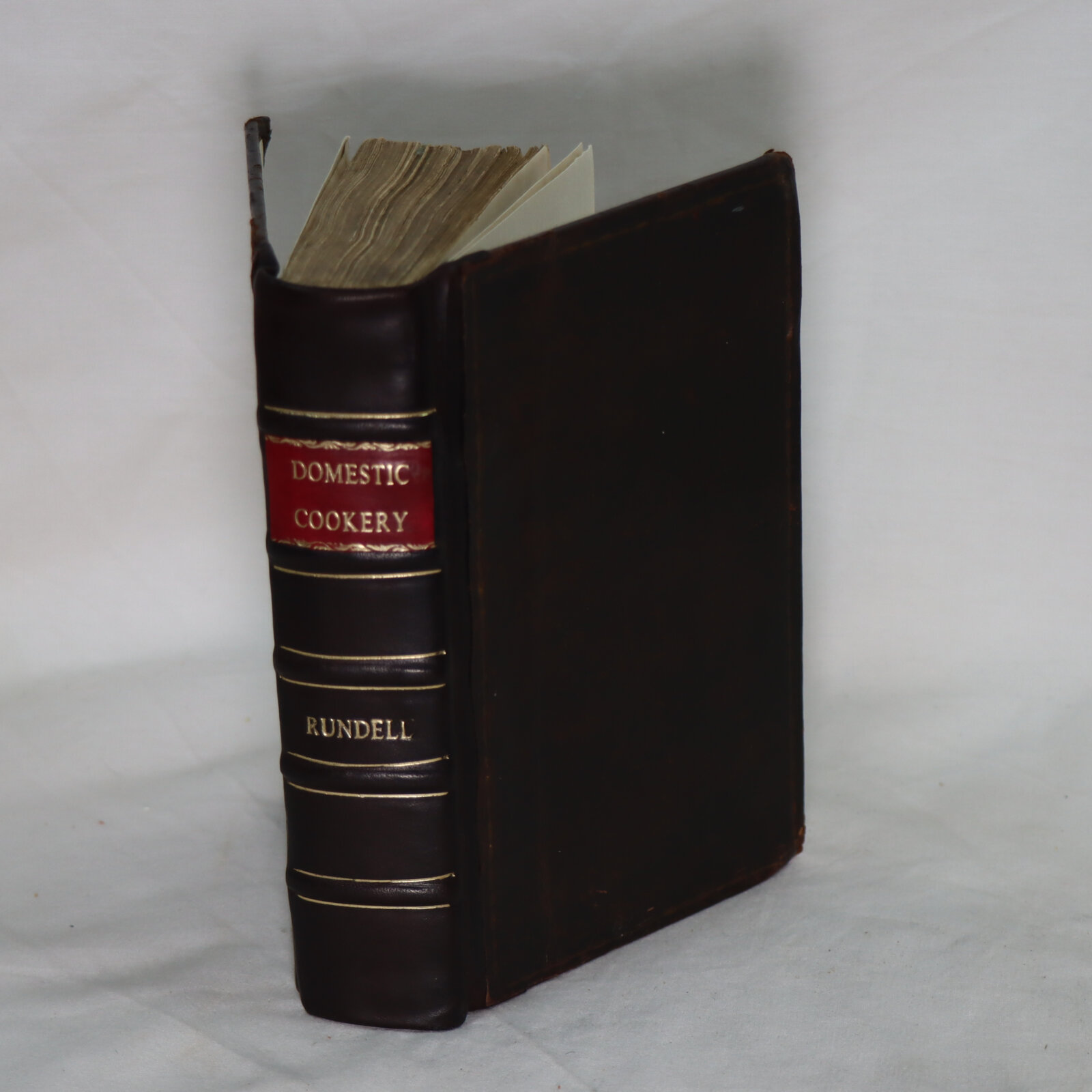

Restored. Brown leather binding with red and black title plate on the rebacked spine.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Full leather and completely restored to a ‘new condition’ by Brian Cole. A truly superb book.

A New System of Domestic Cookery, first published in 1806 by Maria Rundell (1745 – 16 December 1828), was the most popular English cookbook of the first half of the nineteenth century; it is often referred to simply as “Mrs Rundell”, but its full title is A New System of Domestic Cookery: Formed Upon Principles of Economy; and Adapted to the Use of Private Families. Mrs Rundell has been called “the original domestic goddess” and her book “a publishing sensation” and “the most famous cookery book of its time”. It ran to over 67 editions; the 1865 edition had grown to 644 pages, and earned two thousand guineas.

The first edition of 1806 was a short collection of Mrs Rundell’s recipes published by John Murray. It went through dozens of editions, both legitimate and pirated, in both Britain and the United States, where the first edition was published in 1807. The frontispiece typically credited the authorship to “A Lady”. Later editions continued for some forty years after Mrs Rundell’s death. The author Emma Roberts (c. 1794–1840) edited the 64th edition, adding some recipes of her own.

Sales of A New System of Domestic Cookery helped to found the John Murray publishing empire. Sales in Britain were over 245,000; worldwide, over 500,000; the book stayed in print until the 1880s. When Rundell and Murray fell out, she approached a rival publisher, Longman’s, leading to a legal battle.

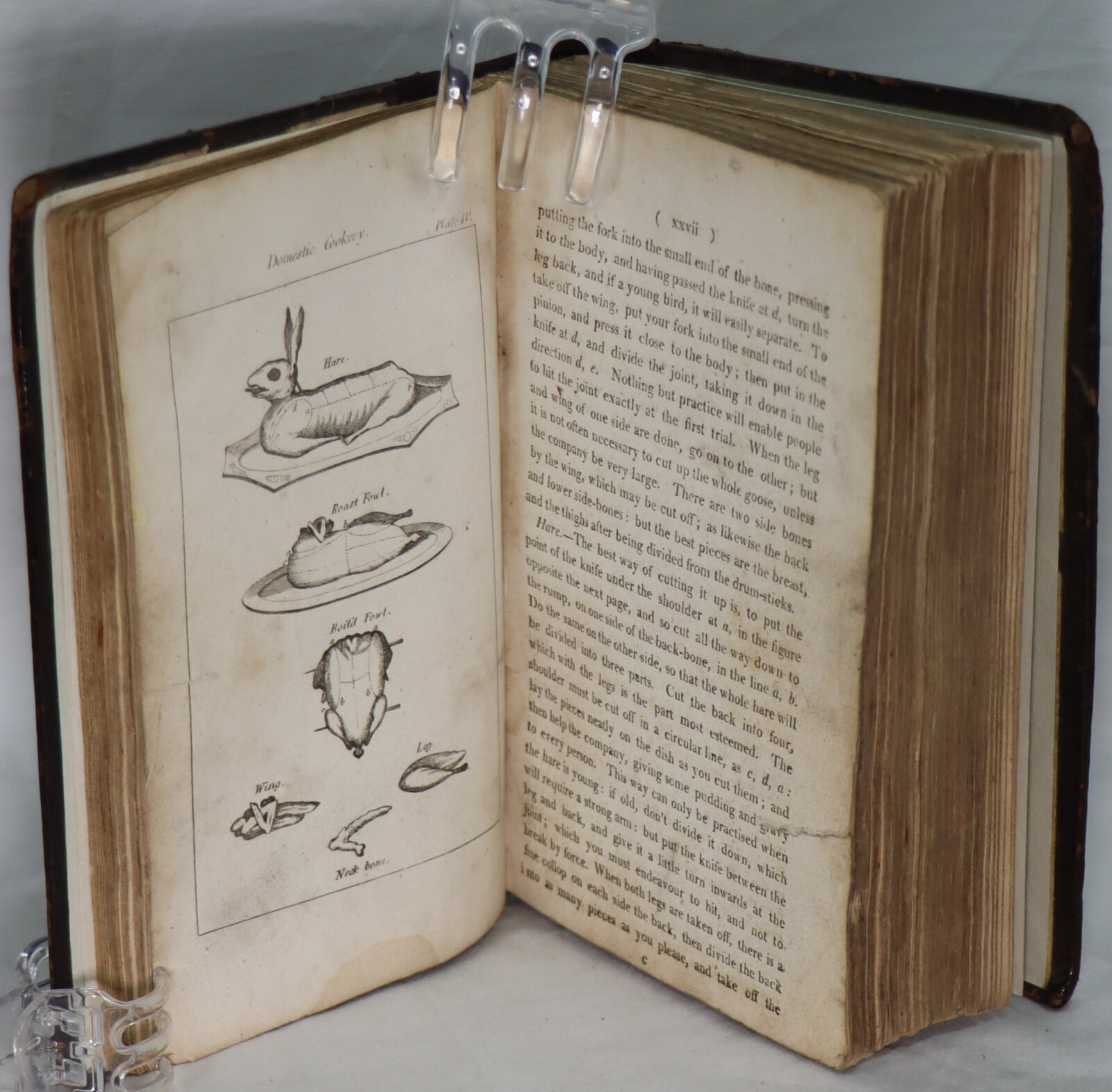

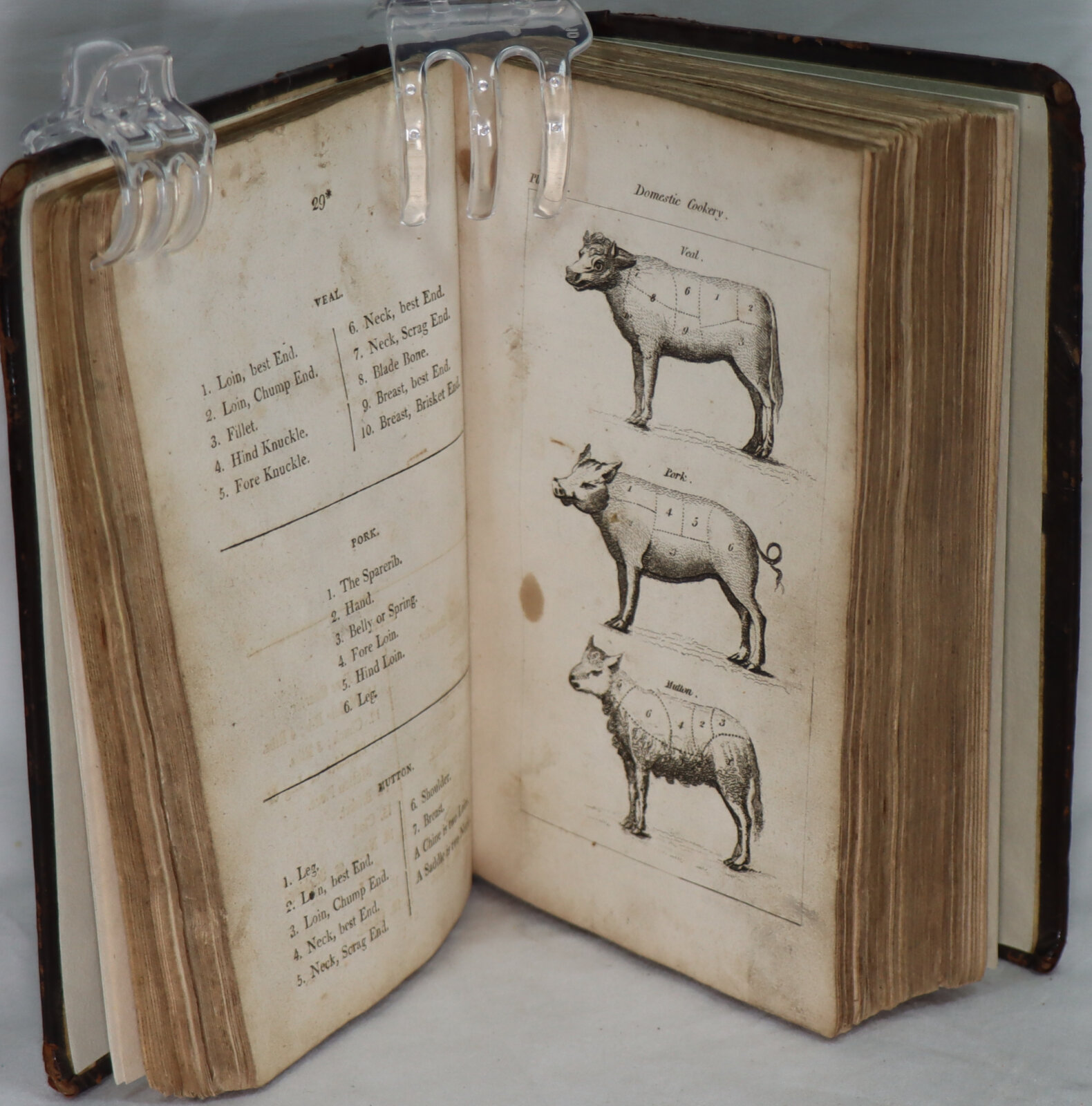

In contrast to the relative disorder of English eighteenth century cookery books such as Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife (1727) or Elizabeth Raffald’s The Experienced English Housekeeper (1769), Mrs Rundell’s text is strictly ordered and neatly subdivided. Where those books consist almost wholly of recipes, Mrs Rundell begins by explaining techniques of economy (“A minute account of the annual income and the times of payment should be kept in writing”), how to carve, how to stew, how to season, to “Look clean, be careful and nice in work, so that those who have to eat might look on”, how to choose and use steam-kettles and the bain-marie, the meanings of foreign terms like pot-au-feu (“truly the foundation of all good cookery”), all the joints of meat, the “basis of all well-made soups”, so it is page 65 before actual recipes begin.

Severin Carrell, writing in The Guardian, calls Mrs Rundell “the original domestic goddess” and her book “a publishing sensation” of the early nineteenth century, as it sold “half a million copies and conquered America”, as well as helping to found the John Murray publishing empire. For all that, Carrell notes, both “the most famous cookery book of its time” and Rundell herself vanished into obscurity.

Elizabeth Grice, writing in The Daily Telegraph, similarly calls Mrs Rundell “a Victorian domestic goddess”, though without “Nigella’s sexual frisson, or Delia’s uncomplicated kitchen manners”. Grice points out that “at 61, she was too old to act the pouting goddess” to sell her book, but “sell it did, in vast numbers, as a lifeline to cash-strapped middle-class English households that were desperate to keep up appearances but they were having trouble with the staff.” She says that compared to Eliza Acton “who could write better” (as in her 1845 book, Modern Cookery for Private Families), and the “ubiquitous” Mrs Beeton, Mrs Rundell “has unfairly slipped from view”.

Alan Davidson, in the Oxford Companion to Food writes that “It did not include many novel features, although it did have one of the first English recipes for tomato sauce.”

Maria Eliza Rundell (née Ketelby; 1745 – 16 December 1828) was an English writer. Little is known about most of her life, but in 1805, when she was over 60, she sent an unedited collection of recipes and household advice to John Murray, of whose family—owners of the John Murray publishing house—she was a friend. She asked for, and expected, no payment or royalties.

Murray published the work, A New System of Domestic Cookery, in November 1805. It was a huge success and several editions followed; the book sold around half a million copies in Rundell’s lifetime. The book was aimed at middle-class housewives. In addition to dealing with food preparation, it offers advice on medical remedies and how to set up a home brewery and includes a section entitled “Directions to Servants”. The book contains an early recipe for tomato sauce—possibly the first—and the first recipe in print for Scotch eggs. Rundell also advises readers on being economical with their food and avoiding waste.

In 1819 Rundell asked Murray to stop publishing Domestic Cookery, as she was increasingly unhappy with the way the work had declined with each subsequent edition. She wanted to issue a new edition with a new publisher. A court case ensued, and legal wrangling between the two sides continued until 1823, when Rundell accepted Murray’s offer of £2,100 for the rights to the work.

Rundell wrote a second book, Letters Addressed to Two Absent Daughters, published in 1814. The work contains the advice a mother would give to her daughters on subjects such as death, friendship, how to behave in polite company and the types of books a well-mannered young woman should read. She died in December 1828 while visiting Lausanne, Switzerland.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend