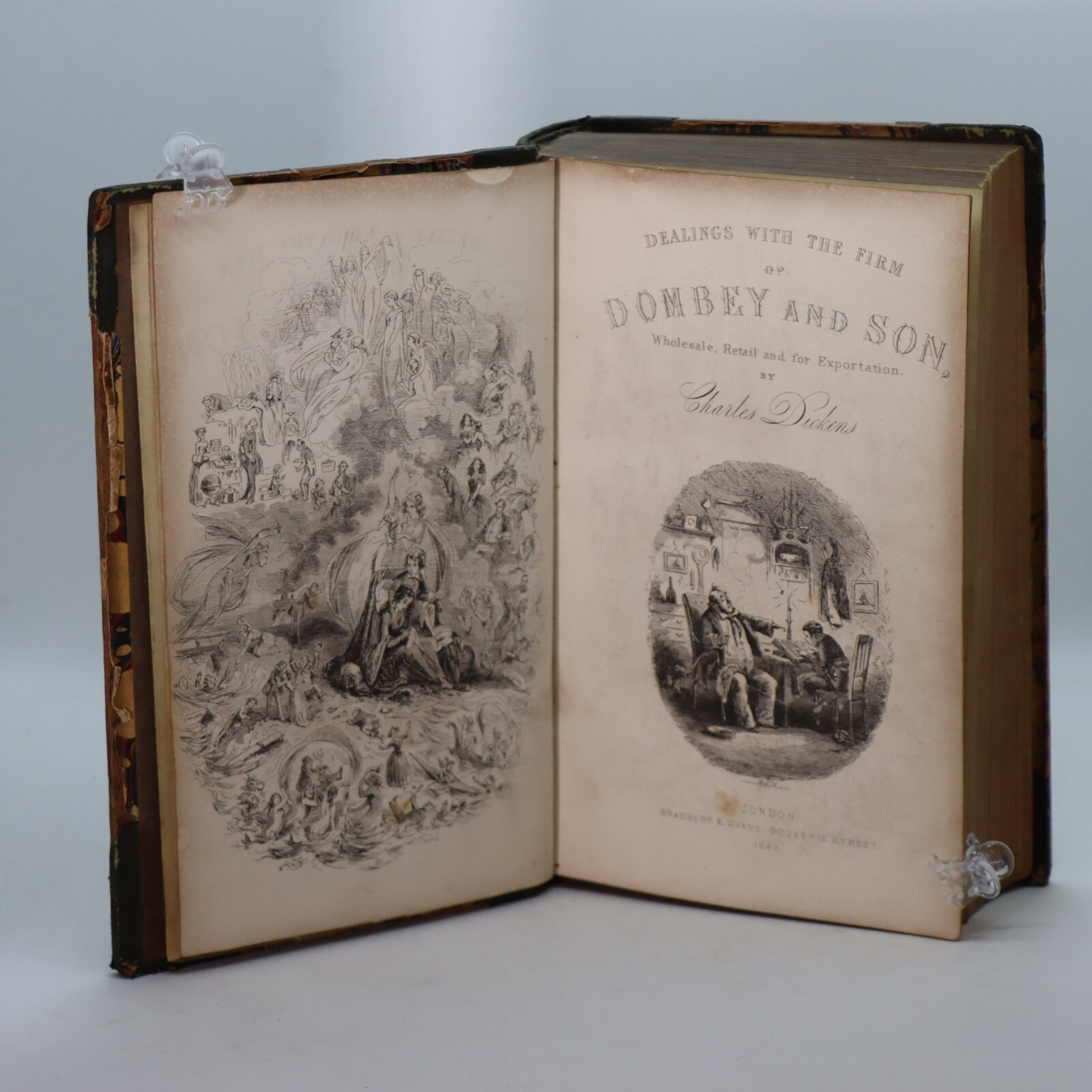

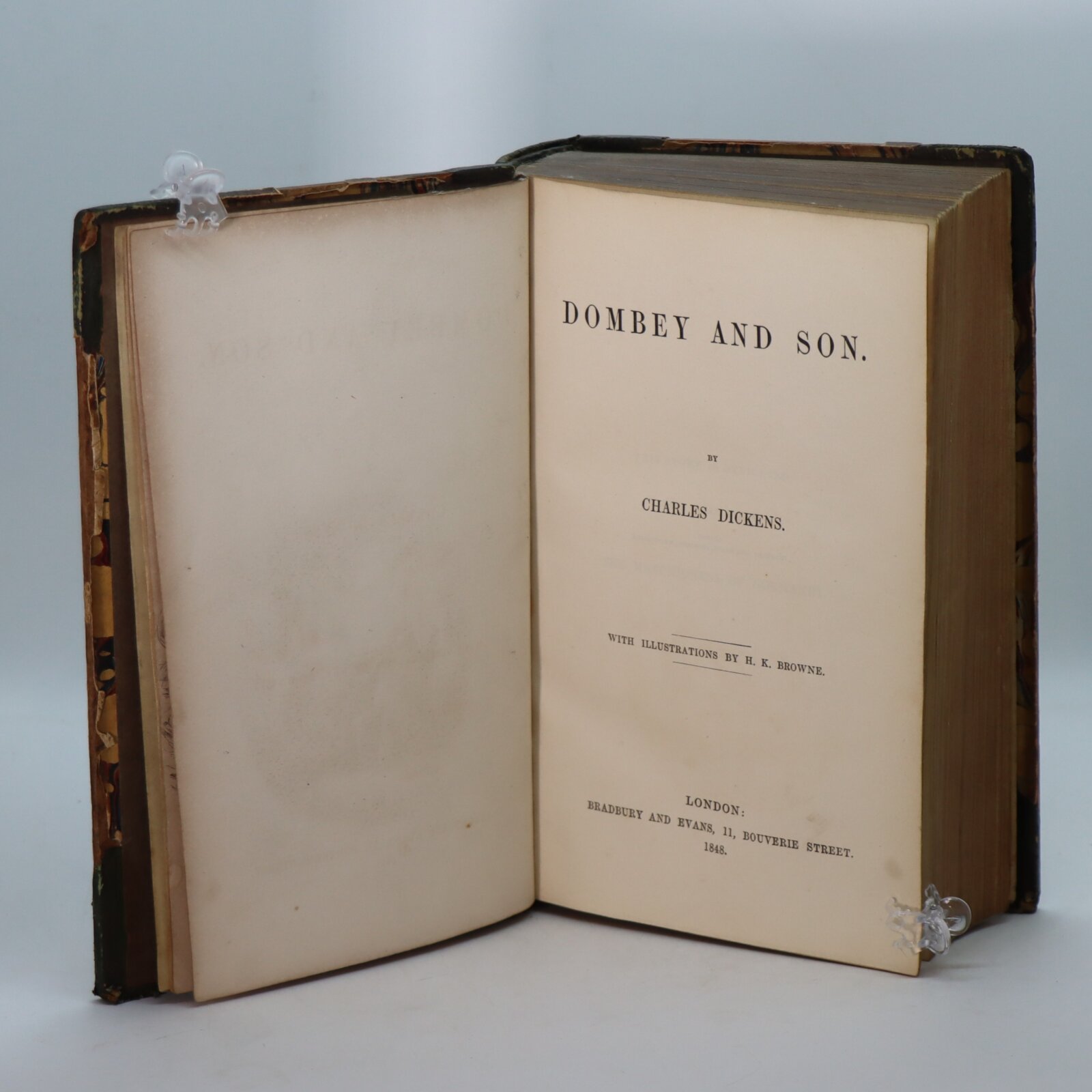

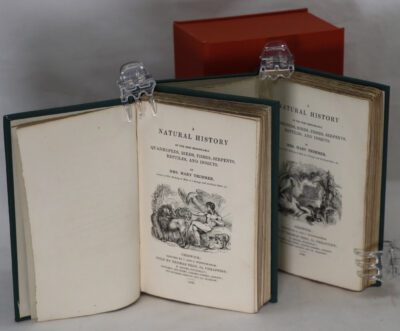

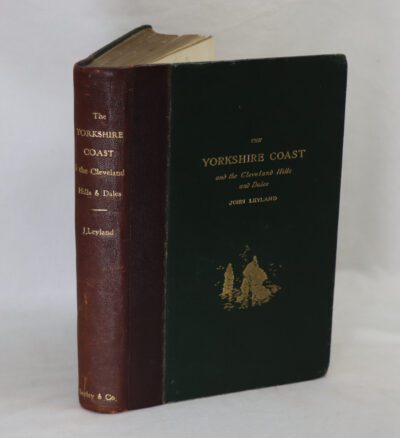

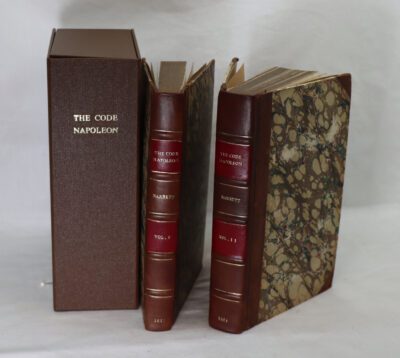

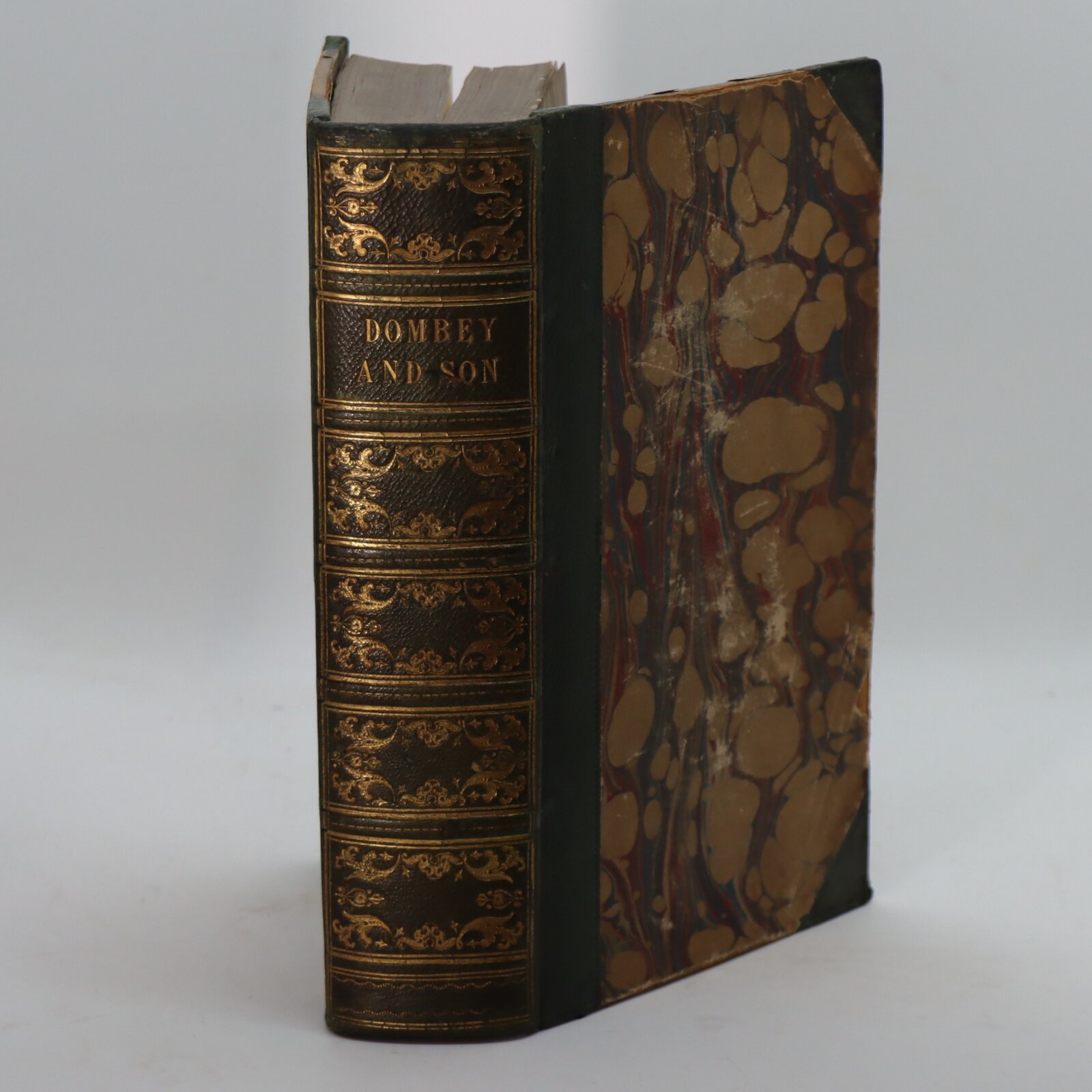

Dombey and Son. 1848.

By Charles Dickens

Printed: 1848

Publisher: Bradbury & Evans. London

Edition: First edition

| Dimensions | 15 × 22 × 5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 15 x 22 x 5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Your items

Item information

Description

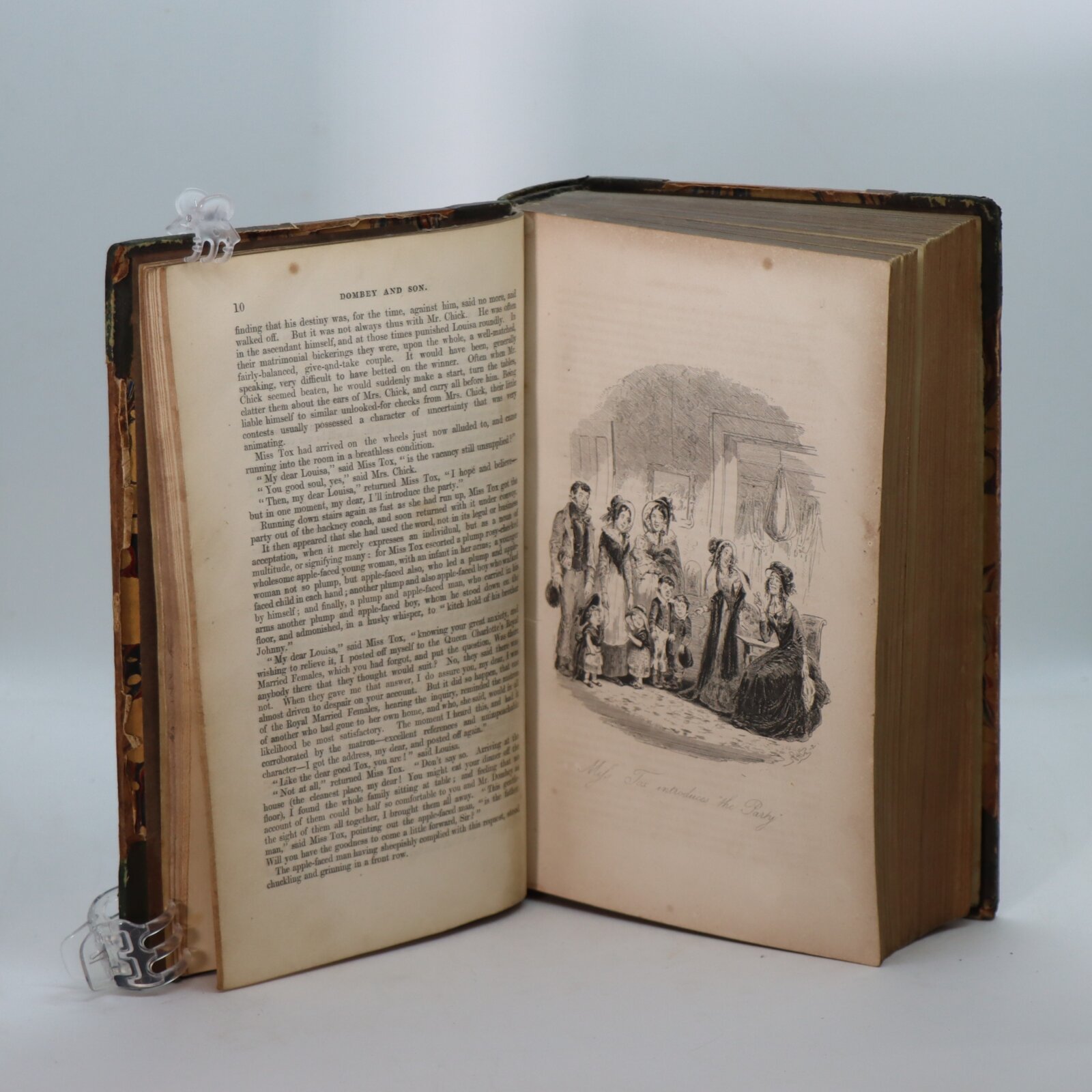

Red Leather spine and corners. Red and blue marbled paper boards Gilt title, banding and decoration on the spine. Illustrations by Phiz.

It is the intent of F.B.A. to provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this book offered so to almost stimulate your feel and touch on the book. If requested, more traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Very Good condition, Hablot K Browne “Phiz” (illustrator). First Edition

Dombey and Son is a novel by English author Charles Dickens. It follows the fortunes of a shipping firm owner, who is frustrated at the lack of a son to follow him in his footsteps; he initially rejects his daughter’s love before eventually becoming reconciled with her before his death.

The story features many Dickensian themes, such as arranged marriages, child cruelty, betrayal, deceit, and relations between people from different British social classes. The novel was first published in monthly parts between 1846 and 1848, with illustrations by Hablot Knight Browne (“Phiz”).

Dombey and Son appeared in monthly parts from 1 October 1846 to 1 April 1848 and in one volume in 1848. Its full title is Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son: Wholesale, Retail and for Exportation. Dickens started writing the book in Lausanne, Switzerland, before returning to England, via Paris, to complete it.

PLOT SUMMARY

The story concerns Paul Dombey, the wealthy owner of the shipping company of the book’s title, whose dream is to have a son to continue his business. The book begins when his son is born and Dombey’s wife dies shortly after giving birth. Following the advice of Mrs Louisa Chick, his sister, Dombey employs a wet nurse named Mrs Richards (Toodle). Dombey already has a six-year-old daughter Florence, but, bitter at her not having been the desired boy, he neglects her continually. One day, Mrs Richards, Florence, and her maid, Susan Nipper, secretly pay a visit to Mrs Richard’s house in Staggs’s Gardens so that Mrs Richards can see her children. During this trip, Florence becomes separated from them and is kidnapped for a short time by Good Mrs Brown, before being returned to the streets. She makes her way to Dombey and Son’s offices in the city and there is found and brought home by Walter Gay, an employee of Mr Dombey, who first introduces her to his uncle, the navigation instrument maker Solomon Gills, at his shop The Wooden Midshipman.

The child, named Paul after his father, is a weak and sickly child, who does not socialise normally with others; adults call him “old fashioned”. He is intensely fond of his sister Florence, who is deliberately neglected by her father as a supposedly irrelevant distraction. Paul is sent to the seaside at Brighton for his health, where he and Florence lodge with the ancient and acidic Mrs Pipchin. Finding his health beginning to improve there, Mr Dombey keeps him at Brighton and has him educated there at Dr and Mrs Blimber’s school, where he and the other boys undergo both an intense and arduous education under the tutelage of Mr Feeder, B.A. and Cornelia Blimber. It is here that Paul is befriended by a fellow pupil, the amiable but weak-minded Mr Toots.

Here, Paul’s health declines even further in this “great hothouse” and he finally dies, still only six years old. Dombey pushes his daughter away from him after the death of his son, while she futilely tries to earn his love. In the meantime, young Walter is sent off to fill a junior position in the firm’s counting house in Barbados through the manipulations of Mr Dombey’s confidential manager, Mr James Carker, “with his white teeth”, who sees him as a potential rival through his association with Florence. His boat is reported lost and he is presumed drowned. Walter’s uncle leaves to go in search of Walter, leaving his great friend Captain Edward Cuttle in charge of The Midshipman. Meanwhile, Florence is now left alone with few friends to keep her company.

Dombey goes to Leamington Spa with a new friend, Major Joseph B. Bagstock. The Major deliberately sets out to befriend Dombey to spite his neighbour in Princess’s Place, Miss Tox, who has turned cold towards him owing to her hopes – through her close friendship with Mrs Chick – of marrying Mr Dombey. At the spa, Dombey is introduced via the Major to Mrs Skewton and her widowed daughter, Mrs Edith Granger. Mr Dombey, on the lookout for a new wife since his son’s death, considers Edith a suitable match due to her accomplishments and family connections; he is encouraged by both the Major and her avaricious mother, but obviously feels no affection for her. After they return to London, Dombey remarries, effectively “buying” the beautiful but haughty Edith as she and her mother are in a poor financial state. The marriage is loveless; his wife despises Dombey for his overbearing pride and herself for being shallow and worthless. Her love for Florence initially prevents her from leaving, but finally she conspires with Mr Carker to ruin Dombey’s public image by running away together to Dijon. They do so after her final argument with Dombey in which he once again attempts to subdue her to his will. When he discovers that she has left him, he blames Florence for siding with her stepmother, striking her on the breast in his anger. Florence is forced to run away from home. Highly distraught, she finally makes her way to The Midshipman where she lodges with Captain Cuttle as he attempts to restore her to health. They are visited frequently by Mr Toots and his prizefighter companion, the Chicken, since Mr Toots has been desperately in love with Florence since their time together in Brighton.

Dombey sets out to find his wife. He is helped by Mrs Brown and her daughter, Alice, who, as it turns out, was a former lover of Mr Carker. After being transported as a convict for criminal activities, which Mr Carker had involved her in, she is seeking her revenge against him now that she has returned to England. Going to Mrs Brown’s house, Dombey overhears the conversation between Rob the Grinder – who is in the employment of Mr Carker – and the old woman as to the couple’s whereabouts and sets off in pursuit. In the meantime, in Dijon, Mrs Dombey informs Carker that she sees him in no better a light than she sees Dombey, that she will not stay with him, and she flees their apartment. Distraught, with both his financial and personal hopes lost, Carker flees from his former employer’s pursuit. He seeks refuge back in England, but being greatly overwrought, accidentally falls under a train and is killed.

After Carker’s death, it is discovered that he had been running the firm far beyond its means. This information is gleaned by Carker’s brother and sister, John and Harriet, from Mr Morfin, the assistant manager at Dombey and Son, who sets out to help John Carker. He often overheard the conversations between the two brothers in which James, the younger, often abused John, the older, who was just a lowly clerk and who is sacked by Dombey because of his filial relationship to the former manager. As his nearest relations, John and Harriet inherit all Carker’s ill-gotten gains, to which they feel they have no right. Consequently, they surreptitiously give the proceeds to Mr Dombey, through Mr Morphin, who is instructed to let Dombey believe that they are merely something forgotten from the general wreck of his fortunes. Meanwhile, back at The Midshipman, Walter reappears, having been saved by a passing ship after floating adrift with two other sailors on some wreckage. After some time, he and Florence are finally reunited – not as “brother” and “sister” but as lovers, and they marry prior to sailing for China on Walter’s new ship. This is also the time when Sol Gills returns to The Midshipman. As he relates to his friends, he received news whilst in Barbados that a homeward-bound China trader had picked up Walter and so had returned to England immediately. He said he had sent letters whilst in the Caribbean to his friend Ned Cuttle c/o Mrs MacStinger at Cuttle’s former lodgings, and the bemused Captain recounts how he fled the place, thus never receiving them.

Florence and Walter depart, and Sol Gills is entrusted with a letter, written by Walter to her father, pleading for him to be reconciled towards them both. A year passes and Alice Brown has slowly been dying despite the tender care of Harriet Carker. One night Alice’s mother reveals that Alice herself is the illegitimate cousin of Edith Dombey (which accounts for their similarity in appearance when they both meet). In a chapter entitled “Retribution”, Dombey and Son goes bankrupt. Dombey retires to two rooms in his house and all its contents are put up for sale. Mrs Pipchin, for some time the housekeeper, dismisses all the servants and she herself returns to Brighton, to be replaced by Mrs Richards. Dombey spends his days sunk in gloom, seeing no-one, and thinking only of his daughter:

He thought of her as she had been that night when he and his bride came home. He thought of her as she had been in all the home events of the abandoned house. He thought, now, that of all around him, she alone had never changed. His boy had faded into dust, his proud wife had sunk into a polluted creature, his flatterer and friend had been transformed into the worst of villains, his riches had melted away, the very walls that sheltered him looked on him as a stranger; she alone had turned the same, mild gentle look upon him always. Yes, to the latest and the last. She had never changed to him – nor had he ever changed to her – and she was lost.

However, one day Florence returns to the house with her baby son, Paul, and is lovingly reunited with her father.

Dombey accompanies his daughter to her and Walter’s house where he slowly starts to decline, cared for by Florence and Susan Nipper, now Mrs Toots. They receive a visit from Edith’s Cousin Feenix who takes Florence to Edith for one final time – Feenix sought Edith out in France, and she returned to England under his protection. Edith gives Florence a letter, asking Dombey to forgive her crime before her departure to the South of Italy with her elderly relative. As she says to Florence, “I will try, then to forgive him his share of the blame. Let him try to forgive me mine!”

The final chapter (LXII) sees Dombey now a white-haired old man “whose face bears heavy marks of care and suffering; but they are traces of a storm that has passed on for ever, and left a clear evening in its track”. Sol Gills and Ned Cuttle are now partners at The Midshipman, a source of great pride to the latter, and Mr and Mrs Toots announce the birth of their third daughter. Walter is doing well in business, having been appointed to a position of great confidence and trust, and Dombey is the proud grandfather of both a grandson and granddaughter whom he dotes on. The book ends with the moving lines:

“Dear grandpapa, why do you cry when you kiss me?”

He only answers, “Little Florence! Little Florence!” and smooths away the curls that shade her earnest eyes.

Dombey and Son was conceived first and foremost as a continuous novel. A letter from Dickens to Forster on 26 July 1846 shows the major details of the plot and theme already substantially worked out. According to the novelist George Gissing,

Dombey was begun at Lausanne, continued at Paris, completed in London, and at English seaside places; whilst the early parts were being written, a Christmas story, The Battle of Life, was also in hand, and Dickens found it troublesome to manage both together. That he overcame the difficulty—that, soon after, we find him travelling about England as member of an amateur dramatic company—that he undertook all sorts of public engagements and often devoted himself to private festivity—Dombey going on the while, from month to month—is matter enough for astonishment to those who know anything about artistic production. But such marvels become commonplaces in the life of Charles Dickens.

There is some evidence to suggest that Dombey and Son was inspired by the life of Christopher Huffam, Rigger to His Majesty’s Navy, a gentleman and head of an established firm, Huffam & Son. Charles Dickens’ father, John Dickens, at the time a clerk in the Navy Pay Office, asked the wealthy, well-connected Huffam to act as godfather to Charles. This same Huffam family appeared later in Charles Palliser’s 1989 The Quincunx, a homage to the Dickensian novel form.

As with most of Dickens’ work, a number of socially significant themes are to be found in this book. In particular the book deals with the then-prevalent common practice of arranged marriages for financial gain. Other themes to be detected within this work include child cruelty (particularly in Dombey’s treatment of Florence), familial relationships, and as ever in Dickens, betrayal and deceit and the consequences thereof. Another strong central theme, which the critic George Gissing elaborates on in detail in his 1925 work The Immortal Dickens, is that of pride and arrogance, of which Paul Dombey senior is the extreme exemplification in Dickens’ work.

Gissing makes a number of points about certain key inadequacies in the novel, not the least that Dickens’s central character is largely unsympathetic and an unsuitable vehicle and also that after the death of the young Paul Dombey the reader is somewhat estranged from the rest of what is to follow. He notes that “the moral theme of this book was Pride—pride of wealth, pride of place, personal arrogance. Dickens started with a clear conception of his central character and of the course of the story in so far as it depended upon that personage; he planned the action, the play of motive, with unusual definiteness, and adhered very closely in the working to this well-laid scheme”. However, he goes on to write that “Dombey and Son is a novel which in its beginning promises more than its progress fulfils” and gives the following reasons why:

Impossible to avoid the reflection that the death of Dombey’s son and heir marks the end of a complete story, that we feel a gap between Chapter XVI and what comes after (the author speaks of feeling it himself, of his striving to “transfer the interest to Florence”) and that the narrative of the later part is ill-constructed, often wearisome, sometimes incredible. We miss Paul, we miss Walter Gay (shadowy young hero though he be); Florence is too colourless for deep interest, and the second Mrs Dombey is rather forced upon us than accepted as a natural figure in the drama. Dickens’s familiar shortcomings are abundantly exemplified. He is wholly incapable of devising a plausible intrigue and shocks the reader with monstrous improbabilities such as all that portion of the denouement in which old Mrs Brown and her daughter are concerned. A favourite device with him (often employed with picturesque effect) was to bring into contact persons representing widely severed social ranks; in this book the “effect” depends too often on “incidences of the boldest artificiality,” as nearly always we end by neglecting the story as a story, and surrendering ourselves to the charm of certain parts, the fascination of certain characters.

Characters in the novel

Karl Ashley Smith, in his introduction to Wordsworth Classics’ edition of Dombey and Son, makes some reflections on the novel’s characters. He believes that Dombey’s power to disturb comes from his belief that human relationships can be controlled by money, giving the following examples to support this viewpoint:

He tries to prevent Mrs Richards from developing an attachment to Paul by emphasising the wages he pays her. Mrs Pipchin’s small talk satisfies him as “the sort of thing for which he paid her so much a quarter” (p.132). Worst of all, he effectively buys his second wife and expects that his wealth and position in society will be enough to keep her in awed obedience to him. Paul’s questions about money are only the first indication of the naivety of his outlook.

However, he also believes that the satire against this man is tempered with compassion.

Smith also draws attention to the fact that certain characters in the novel “develop a pattern from Dickens’s earlier novels, whilst pointing the way to future works”. One such character is Little Paul who is a direct descendant of Little Nell. Another is James Carker, the ever-smiling manager of Dombey and Son. Smith notes there are strong similarities between him and the likes of Jaggers in Great Expectations and, even more so, the evil barrister, Mr Tulkinghorn, in Bleak House:

From Fagin (Oliver Twist) onwards, the terrifying figure exerting power over others by an infallible knowledge of their secrets becomes one of the author’s trademarks … James Carker’s gentlemanly businesslike respectability marks him out as the ancestor of Tulkinghorn in Bleak House and even of Jaggers in Great Expectations. And his involvements in the secrets of others leads him to as sticky an end as Tulkinghorn’s. The fifty-fifth chapter, where he is forced to flee his outraged employer, magnificently continues the theme of the guilt-hunted man from Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist and Jonas’s restless sense of pursuit in Martin Chuzzlewit. There is always a strong sense in Dickens of the narrative drive of discovery catching up with those who deal in darkness.

Gissing looks at some of the minor characters in the novel and is particularly struck by that of Edward (Ned) Cuttle.

Captain Cuttle has a larger humanity than his roaring friend [Captain Bunsby], he is the creation of humour. That the Captain suffered dire things at the hands of Mrs MacStinger is as credible as it is amusing, but he stood in no danger of Bunsby’s fate; at times he can play his part in a situation purely farcical, but the man himself moves on a higher level. He is one of the most familiar to us among Dickens’s characters, an instance of the novelist’s supreme power, which (I like to repeat) proves itself in the bodying forth of a human personality henceforth accepted by the world. His sentences have become proverbs; the mention of his name brings before the mind’s eye an image of flesh and blood – rude, tending to the grotesque, but altogether lovable. Captain Cuttle belongs to the world of Uncle Toby, with, to be sure, a subordinate position. Analyse him as you will, make the most of those extravagances which pedants of to-day cannot away with, and in the end you will still be face to face with something vital – explicable only as the product of genius.

Charles John Huffam Dickens FRSA (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world’s best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era. His works enjoyed unprecedented popularity during his lifetime and, by the 20th century, critics and scholars had recognised him as a literary genius. His novels and short stories are widely read today.

Born in Portsmouth, Dickens left school to work in a factory when his father was incarcerated in a debtors’ prison. Despite his lack of formal education, he edited a weekly journal for 20 years, wrote 15 novels, five novellas, hundreds of short stories and non-fiction articles, lectured and performed readings extensively, was an indefatigable letter writer, and campaigned vigorously for children’s rights, education and other social reforms.

Dickens’s literary success began with the 1836 serial publication of The Pickwick Papers, a publishing phenomenon—thanks largely to the introduction of the character Sam Weller in the fourth episode—that sparked Pickwick merchandise and spin-offs. Within a few years Dickens had become an international literary celebrity, famous for his humour, satire and keen observation of character and society. His novels, most of them published in monthly or weekly instalments, pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication. Cliffhanger endings in his serial publications kept readers in suspense. The instalment format allowed Dickens to evaluate his audience’s reaction, and he often modified his plot and character development based on such feedback. For example, when his wife’s chiropodist expressed distress at the way Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield seemed to reflect her disabilities, Dickens improved the character with positive features. His plots were carefully constructed and he often wove elements from topical events into his narratives. Masses of the illiterate poor would individually pay a halfpenny to have each new monthly episode read to them, opening up and inspiring a new class of readers.

His 1843 novella A Christmas Carol remains especially popular and continues to inspire adaptations in every artistic genre. Oliver Twist and Great Expectations are also frequently adapted and, like many of his novels, evoke images of early Victorian London. His 1859 novel A Tale of Two Cities (set in London and Paris) is his best-known work of historical fiction. The most famous celebrity of his era, he undertook, in response to public demand, a series of public reading tours in the later part of his career.

The term Dickensian is used to describe something that is reminiscent of Dickens and his writings, such as poor social or working conditions, or comically repulsive characters.

Dickens gave recitals of his work in FBA’s Bar Street’s neighbouring street in Scarborough.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend