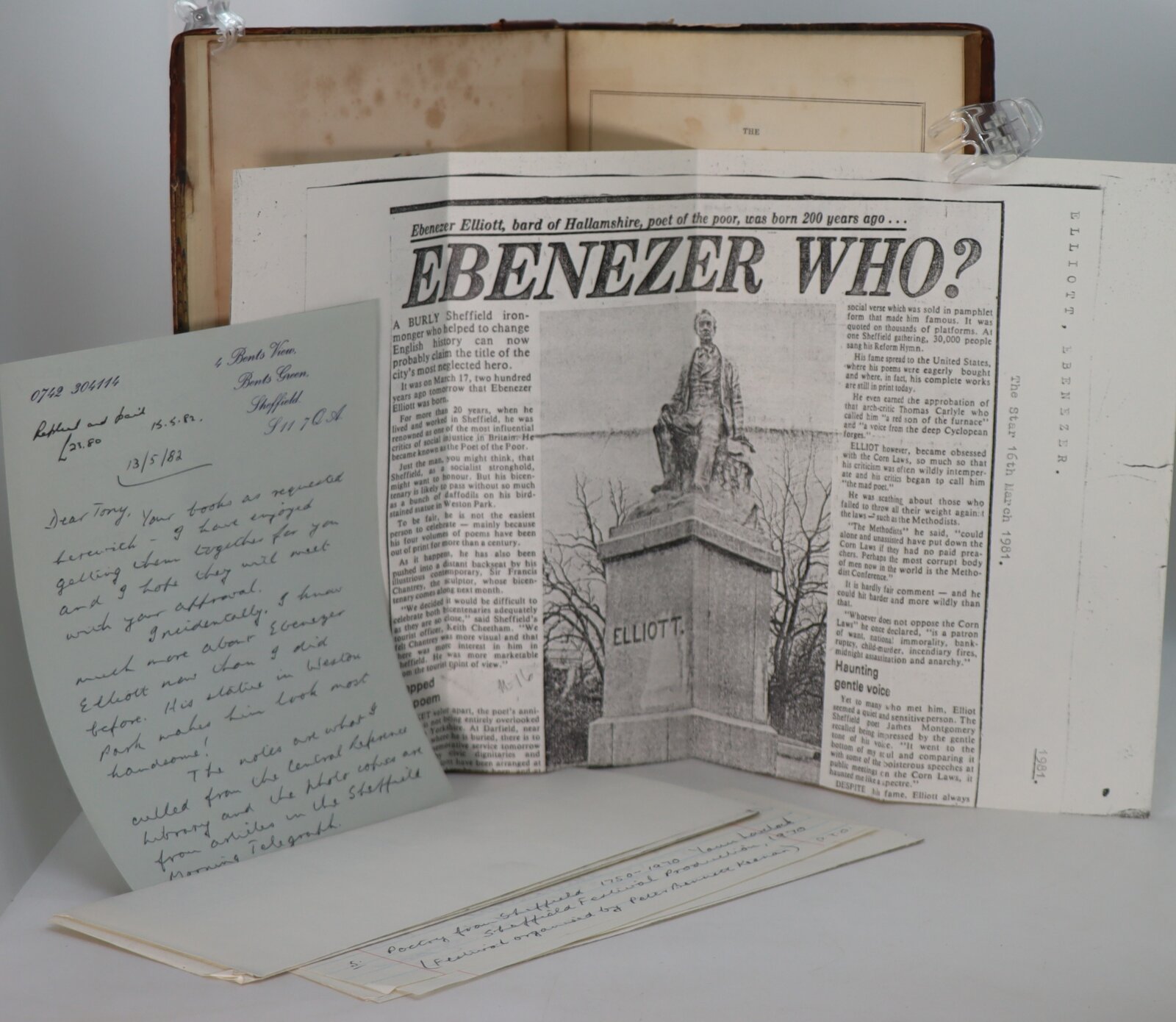

The Works of Ebenezer Elliott.

By Ebenezer Elliott

Printed: 1840

Publisher: William Tait. Edinburgh

| Dimensions | 17 × 26 × 1.5 cm |

|---|

Language: Not stated

Size (cminches): 17 x 26 x 1.5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

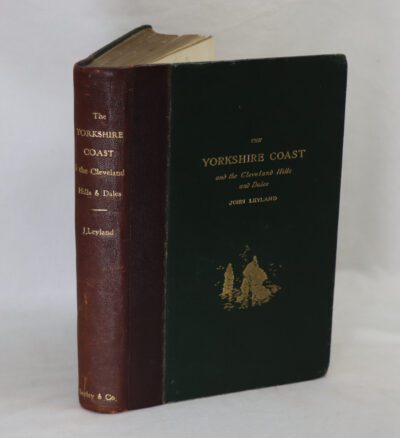

Tan leather spine with black title plate and gilt title. Red and brown marbled boards.

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Very scarce early work containing much ephemera relating to this great man Ebenezer Elliott (17 March 1781 – 1 December 1849) was an English poet, known as the Corn Law rhymer for his leading the fight to repeal the Corn Laws, which were causing hardship and starvation among the poor. Though a factory owner himself, his single-minded devotion to the welfare of the labouring classes won him a sympathetic reputation long after his poetry ceased to be read. Elliott’s poems often seem naive or archaic to the modern reader who gets the impression that Elliott is struggling to write verse – the more he wrestles, the worse he becomes! In a fragment of autobiography printed in The Athenaeum (12 January 1850)

he says that he was entirely self-taught, and attributes his poetic development to long country walks undertaken in search of wildflowers, and to a collection of books, including the works of Young, Barrow, Shenstone and John Milton, bequeathed to his father. His son-in-law, John Watkins, gave a more detailed account in "The Life, Poetry and Letters of Ebenezer Elliott", published in 1850. One Sunday morning, after a heavy night’s drinking, Elliott missed chapel and visited his Aunt Robinson, where he was enthralled by some colour plates of flowers from Sowerby’s English Botany. When his aunt encouraged him to make his own flower drawings, he was pleased to find he had a flair for it. His younger brother, Giles, whom he had always admired, read him a poem from James Thomson’s ‘The Seasons’, which described polyanthus and auricular flowers, and this was a turning point in Elliott’s life. He realised he could successfully combine his love of nature, and his talent for drawing, by writing poems and decorating them with flower illustrations. In 1798, aged 17, he wrote his first poem, ‘Vernal Walk’, in imitation of James Thompson. He was also influenced by George Crabbe, Lord Byron and the Romantic poets and Robert Southey, who later became Poet Laureate. In 1808 Elliott wrote to Southey asking for advice on getting published. Southey’s welcome reply began a correspondence over the years that reinforced his determination to make a name for himself as a poet. They only met once, but exchanged letters until 1824, and Elliott declared it was Southey who had taught him the art of poetry. Other early poems were Second Nuptials and Night, or the Legend of Wharncliffe, which was described by the Monthly Review as the "Ne plus ultra of German horror and bombast". His Tales of the Night, including The Exile and Bothwell, were of more merit and brought him commendations. His earlier volumes of poems, dealing with romantic themes, received much unfriendly comment, and the faults of Night, the earliest of these, were

pointed out in a long and friendly letter (30 January 1819) from Southey to the author. Elliott had married Frances (Fanny) Gartside in 1806 and they eventually had 13 children. He invested his wife’s fortune in his father’s share of the iron foundry, but the affairs of the family firm were then in a desperate condition and money difficulties hastened his father’s death. Elliott lost everything and went bankrupt in 1816. In 1819 he obtained funds from his wife’s sisters and began another business as an iron dealer in Sheffield. This prospered, and by 1829 he had become a successful iron merchant and steel manufacturer. Paul Rodgers gave the opinion that Elliott ‘has been sorely handled by the painters and engravers…. The published portraits convey scarcely any idea at all of the man.’ Of those that remain, two have been attributed to John Birch, who painted other Sheffield worthies too. One shows him seated with a scroll in his left hand and spectacles dangling from the right. The other has him seated on a boulder, clasping an open book in his lap, with the narrow valley of Black Brook in the background. This spot above the river Rivelin was a favourite of Elliott’s and he is said to have carved his name on a boulder there. A drawing of Elliott by the Scottish artist Margaret Gillies is now in the National Portrait Gallery, London. She had accompanied William Howitt in 1847, when he visited the poet for another interview, and her work was reproduced to illustrate it in Howitt’s Journal. Another seated portrait, book in lap, ‘may be a better picture,’ thought Rodgers, ”but is still less like him.’

Elliott is seated on a rock in Neville Burnard’s statue of him, which was also thought a poor likeness. In its issue on 22 July 1854, The Sheffield Independent reported, ‘Many of the persons in Sheffield who have a vivid remembrance of the features of Ebenezer Elliott will feel disappointed that, in this case, the sculptor had not given a more exact similitude of the man as he

lived,’ but goes on to surmise that this is meant to be a ‘somewhat idealised representation of the Corn Law Rhymer’. In 1875, the work was removed from the city centre to Weston Park, where it remains. The statue figures no more clearly in John Betjeman’s poem ‘An Edwardian Sunday, Broomhill, Sheffield’. ‘Your own Ebenezer,’ he apostrophizes, ‘Looks down from his height/ On back street and alley/ And chemical valley’, which he certainly does not. The poet’s final city dwelling in 1834–1841 was in Upperthorpe, not Broomhill, and bears a blue plaque today. Furthermore, the inscription on the pedestal simply reads Elliott, with no mention of his given name. This is noted, among others, by the Sheffield poet Stanley Cook (1922–1991) in his tribute to the relocated statue. ‘It was not this dog’s convenience wrote the poems,’ he comments, ‘But a man could be put together from passers-by’ still angry at remaining injustices. Rotherham, Elliott’s birthplace, was slower to honour him. In 2009 a work by Martin Heron was erected on what is now known as Rhymer’s Roundabout, near Rotherham. Entitled ‘Harvest’, it depicts stylised ears of corn blowing in the wind, as an allusion to the ‘Corn Law Rhymes’. That same year the

new Wetherspoons pub in Rotherham was named The Corn Law Rhymer and in March 2013 a blue plaque commemorating the poet was placed on the town’s medical walk-in centre, marking the site of the iron foundry where he was born.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend