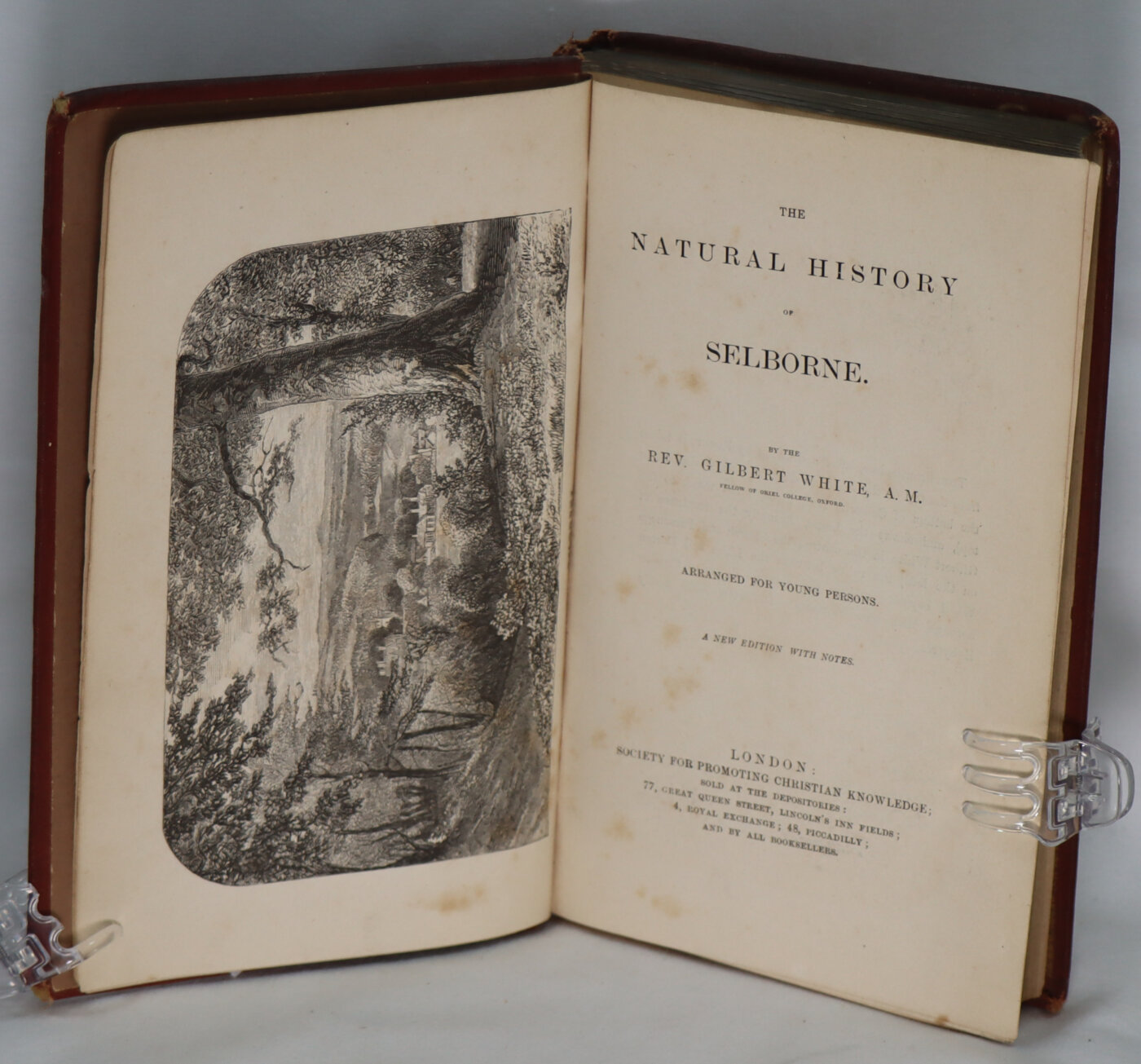

The Natural History of Selborne.

By Rev Gilbert White

Printed: 1833

Publisher: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. London

| Dimensions | 14 × 20 × 2.5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 14 x 20 x 2.5

Condition: Good (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

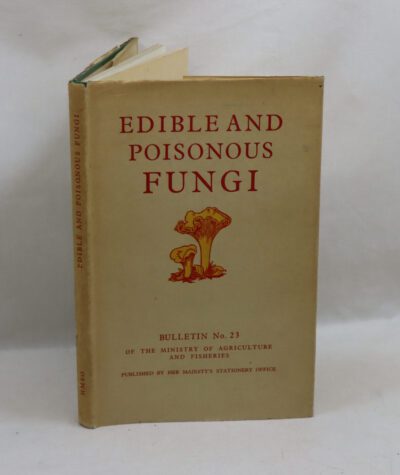

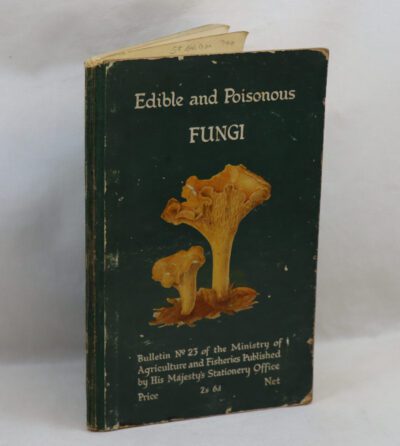

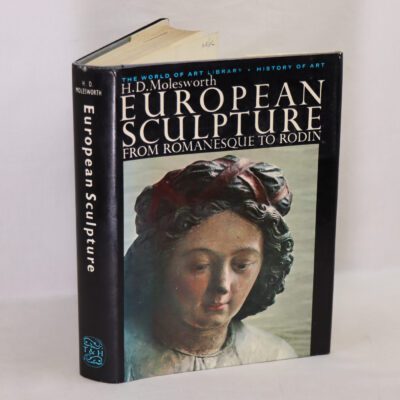

Brown cloth binding with gilt title on the spine and front board.

-

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

-

Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list.

THE NATURAL HISTORY OF SELBORNE. ARRANGED FOR YOUNG PERSONS: Rev. Gilbert White: Publication Date: 1833: Relatively rare.

Condition: Very good. 1833, London, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, new edition, ppx + 345, black and white illustrations, brown cloth, gilt illustration.

The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, or just The Natural History of Selborne is a book by English parson-naturalist Gilbert White (1720–1793). It was first published in 1789 by his brother Benjamin. It has been continuously in print since then, with nearly 300 editions up to 2007.

The book was published late in White’s life, compiled from a mixture of his letters to other naturalists—Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington; a ‘Naturalist’s Calendar’ (in the second edition) comparing phenology observations made by White and William Markwick of the first appearances in the year of different animals and plants; and observations of natural history organized more or less systematically by species and group. A second volume, less often reprinted, covered the antiquities of Selborne. Some of the letters were never posted, and were written for the book.

White’s Natural History was at once well received by contemporary critics and the public, and continued to be admired by a diverse range of nineteenth and twentieth century literary figures. His work has been seen as an early contribution to ecology and in particular to phenology. The book has been enjoyed for its charm and apparent simplicity, and the way that it creates a vision of pre-industrial England.

The original manuscript has been preserved and is displayed in the Gilbert White museum at The Wakes, Selborne.

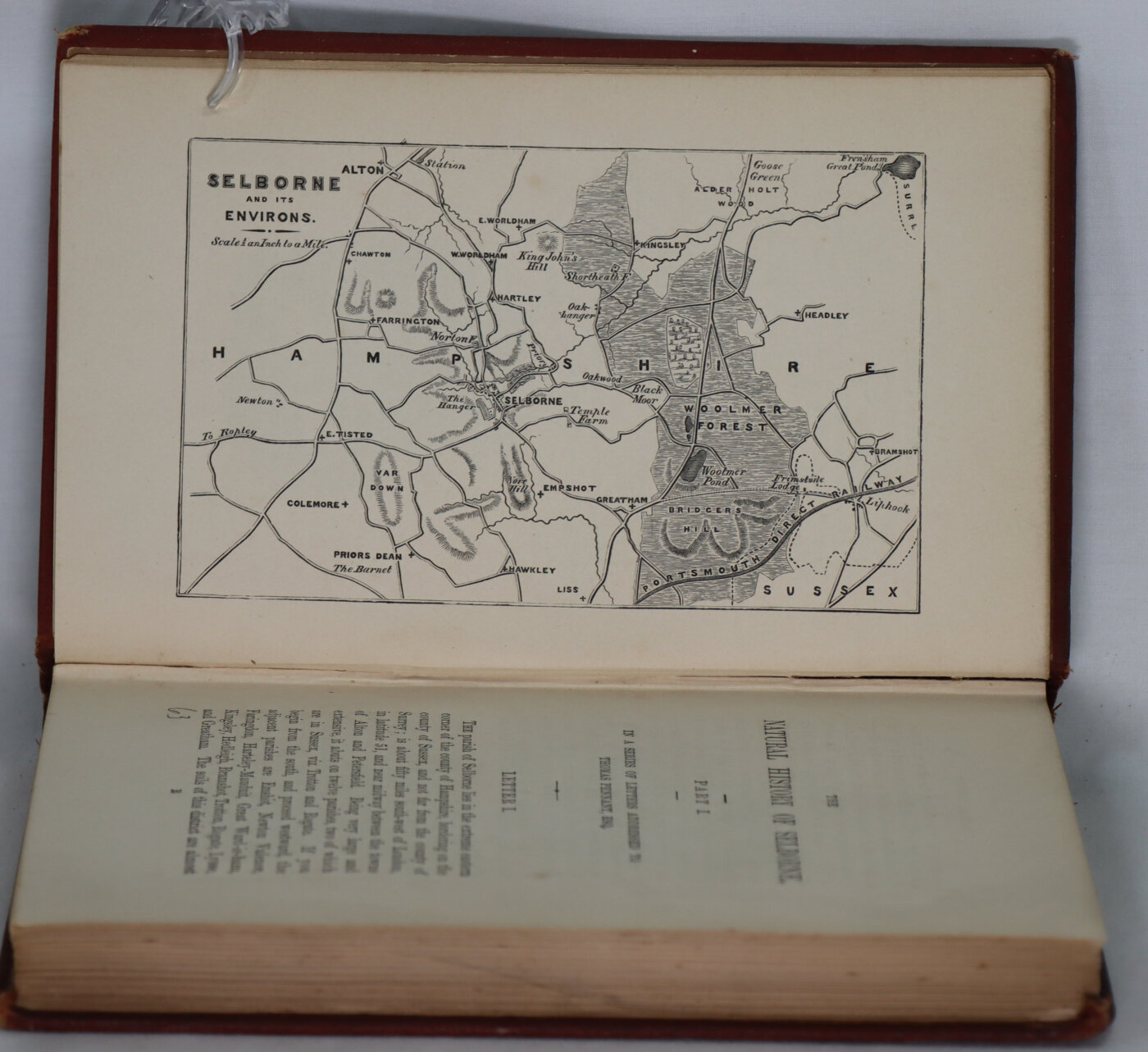

The main part of the book, the Natural History, is presented as a compilation of 44 letters nominally to Thomas Pennant, a leading British zoologist of the day, and 66 letters to Daines Barrington, an English barrister and Fellow of the Royal Society. In these letters, White details the natural history of the area around his family home at the vicarage of Selborne in Hampshire.

Many of the ‘letters’ were never posted, and were written especially for the book. Patrick Armstrong, in his book The English Parson-Naturalist, notes that in particular, “an obvious example is the first, nominally to Thomas Pennant, but which is clearly contrived, as it introduces the parish, briefly summarizing its position, geography and principal physical features.” White’s biographer, Richard Mabey, estimates that up to 46 out of 66 ‘letters to Daines Barrington’ “were probably never sent through the post”; Mabey explains that it is hard to be more precise, because of White’s extensive editing. Some letters are dated although never sent. Some dates have been altered. Some letters have been cut down, split into shorter ‘letters’, merged, or distributed in small parts into other letters. A section about insect-eating birds in a letter sent to Barrington in 1770 appears in the book as letter 41 to Pennant. Personal remarks have been removed throughout. Thus, while the book is genuinely based on letters to Pennant and Barrington, the structure of the book is a literary device.

As a compilation of letters and other materials, the book as a whole has an uneven structure. The first part is a diary-like sequence of ‘letters’, with the breaks and wanderings that naturally follow. The second is a calendar, organized by phenological events around the year. The third is a collection of observations, organised by animal or plant group and species, with a section on meteorology. The apparently rambling structure of the book is in fact bracketed by opening and closing sections, arranged like the rest as letters, which “give form and scale and even a semblance of narrative structure to what would otherwise have been a shapeless anthology.”

The unposted Letter 1 begins:

The parish of Selborne lies in the extreme eastern corner of the county of Hampshire, bordering on the county of Sussex, and not far from the county of Surrey; is about fifty miles south-west of London, in latitude fifty-one, and near mid-way between the towns of Alton and Petersfield. Being very large and extensive, it abuts twelve parishes, two of which are in Sussex—viz, Trotton and Rogate. … The soils of this district are almost as varied and diversified as the views and aspects. The high part of the south-west consists of a vast hill of chalk, rising three hundred feet above the village, and is divided into a sheep-down, the high wood and a long hanging wood, called The Hanger. The covert of this eminence is altogether beech, the most lovely of all forest trees, whether we consider its smooth rind or bark, its glossy foliage, or graceful pendulous boughs. The down, or sheepwalk, is a pleasing park-like spot, of about one mile by half that space, jutting out on the verge of the hill-country, where it begins to break down into the plains, and commanding a very engaging view, being an assemblage of hill, dale, wood-lands, heath, and water. The prospect is bounded to the south-east and east by the vast range of mountains called the Sussex Downs, by Guild-down near Guildford, and by the Downs round Dorking, and Reigate in Surrey, to the north-east, which altogether, with the country beyond Alton and Farnham, form a noble and extensive outline.

“No novelist could have opened better”, wrote Virginia Woolf; “Selborne is set solidly in the foreground.’

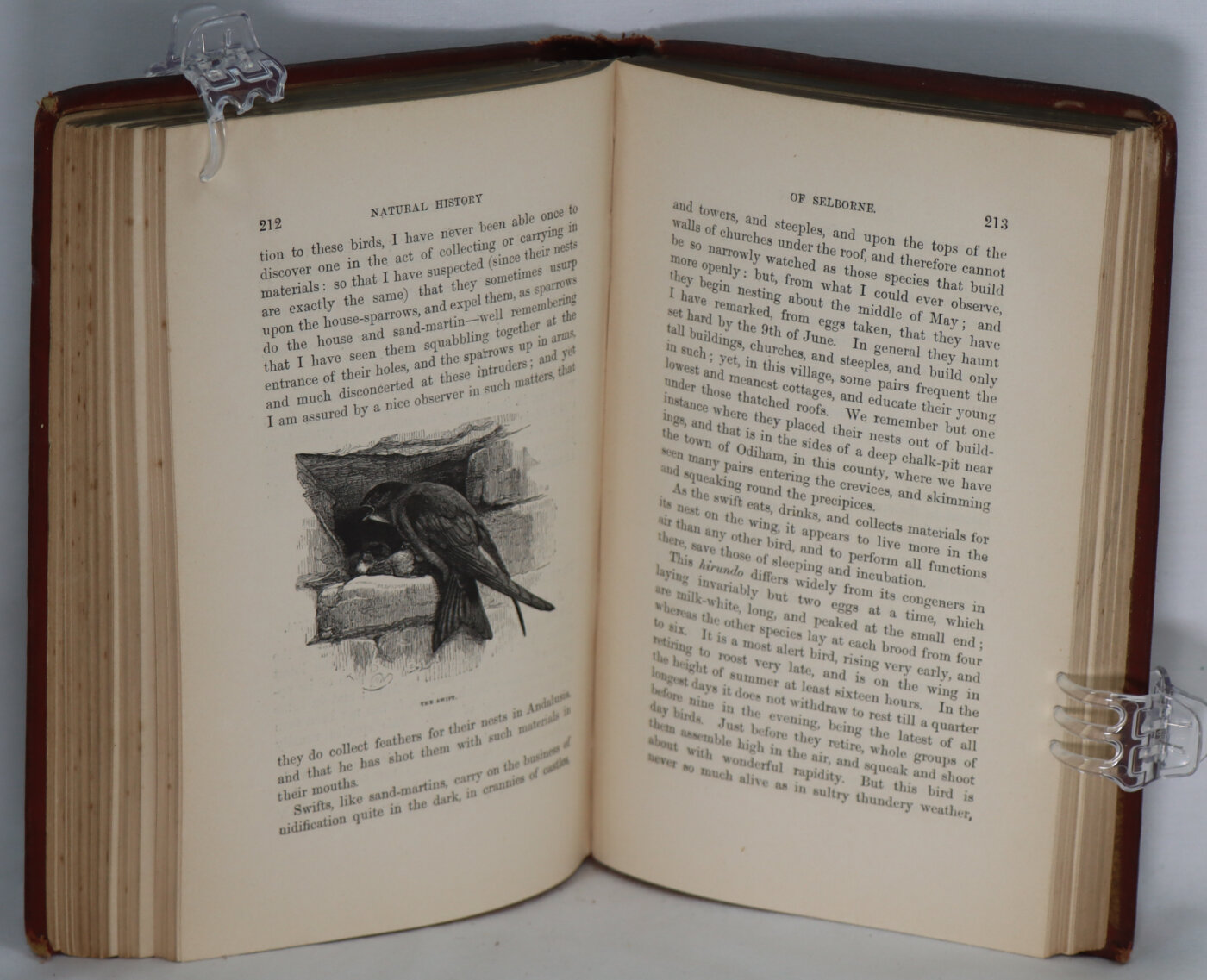

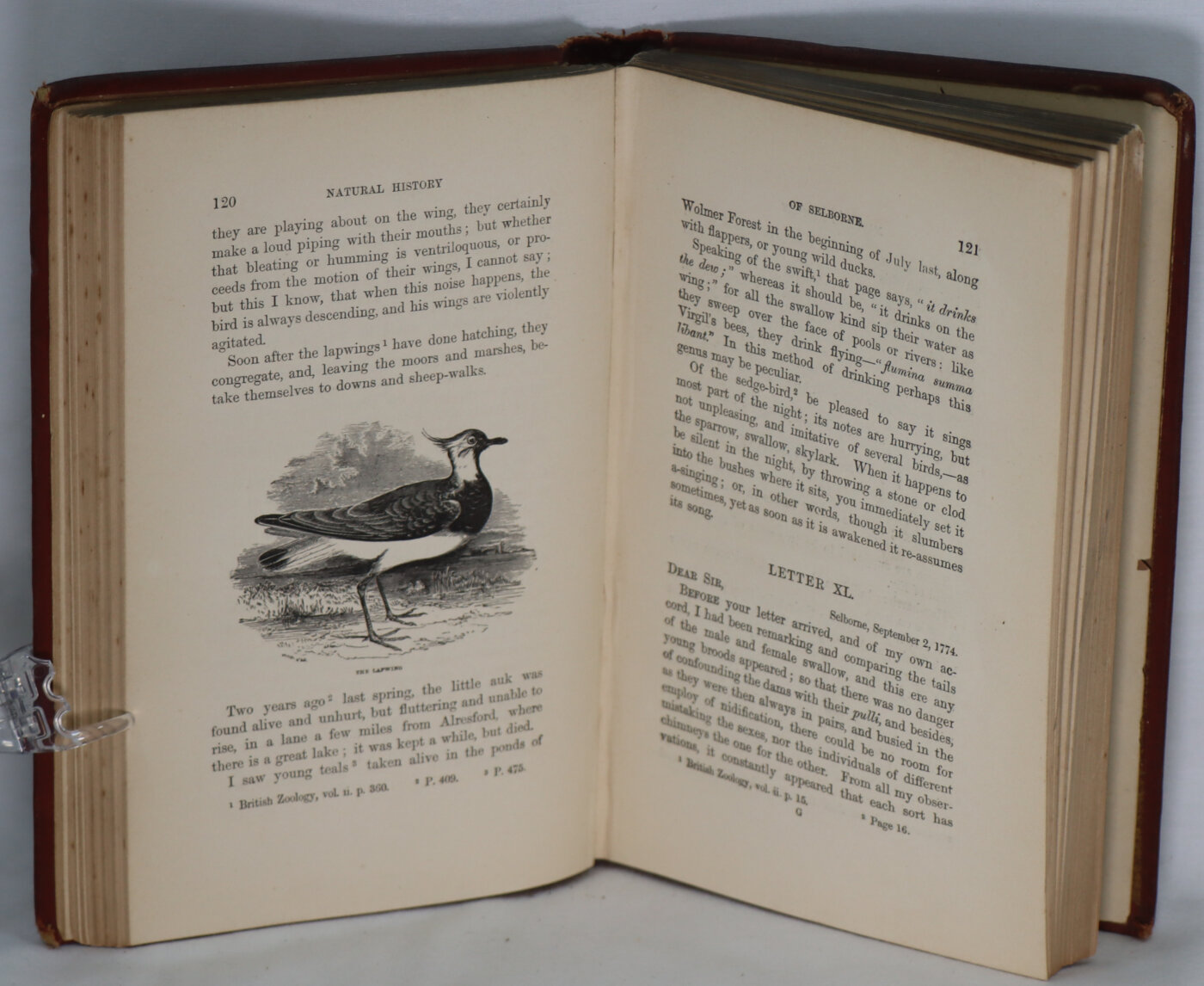

The first edition was illustrated with paintings by the Swiss artist Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, engraved by W. Angus and acquainted. Grimm had lived in England since 1768, and was quite a famous artist, costing 2 1⁄2 guineas per week. In the event, he stayed in Selborne for 28 days, and White recorded that he worked very hard on 24 of them. White also described Grimm’s method, which was to sketch the landscape in lead pencil, then to put in the shading, and finally to add a light wash of watercolour. The illustrations were engraved (signed at lower right) by a variety of engravers including William Angus and Peter Mazell.

Gilbert White (18 July 1720 – 26 June 1793) was a “parson-naturalist”, a pioneering English naturalist, ecologist, and ornithologist. He is best known for his Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne.

Legacy: White has often been seen as an amateur “country writer”, especially by the scientific community. However, he has been called “the indispensable precursor to those great Victorians who would transform our ideas about life on Earth, especially in the undergrowth – Lyell, Spencer, Huxley and Darwin.” He is also under-rated as a pioneer of modern scientific research methods, particularly fieldwork. As Mabey argues, the blending of scientific and emotional responses to Nature was White’s greatest legacy: “it helped foster the growth of ecology and the realisation that humans were also part of the natural scheme of things.”

The White family house in Selborne, The Wakes, now contains the Gilbert White Museum, a registered charity. The Selborne Society was founded in 1895 to perpetuate the memory of Gilbert White. It purchased land by the Grand Union Canal at Perivale in West London to create the first Bird Sanctuary in Britain, known as Perivale Wood. In the 1970s, Perivale Wood became a Local Nature Reserve. This initiative was led by a group of young naturalists, notably Edward Dawson and Peter Edwards, Kevin Roberts and Andrew Duff. It was designated by Ealing Borough Council under the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. Flora Thompson, the countryside novelist, said of White: “It is easy to imagine him, this very first of English nature writers, the most sober and modest, yet happiest of men.”

White is quoted by Merlyn in The Once and Future King by T.H. White and in The Boy in Grey by Henry Kingsley, in which White’s thrush appears as a character. A documentary about White, presented by historian Michael Wood, was broadcast by BBC Four in 2006. White is commemorated in the inscription on one of eight bells installed in 2009 at Holybourne, Hampshire and in the Perivale Wood Local Nature Reserve, which is dedicated to his memory. The Reserve is owned and managed by the Selborne Society, named to commemorate White’s Natural History. White’s frequent accounts of a tortoise inherited from his aunt in The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne form the basis for Verlyn Klinkenborg’s book, Timothy; or, Notes of an Abject Reptile (2006), and for Sylvia Townsend Warner’s The Portrait of a Tortoise (1946).

A stained glass window portraying St Francis of Assisi in Selborne church commemorates Gilbert White. It was designed by Horace Hinckes and was installed in 1920.

White’s influence on artists is celebrated in the exhibition Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists taking place in spring 2020 at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester to mark the 300th anniversary of his birth, and including artworks by Thomas Bewick, Eric Ravilious and John Piper, amongst others.

White is credited with perhaps the earliest written record of the word “golly”, in a journal entry from 1775. Finally, the OED gives White credit for first having used x to represent a kiss in a letter written in 1763.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend