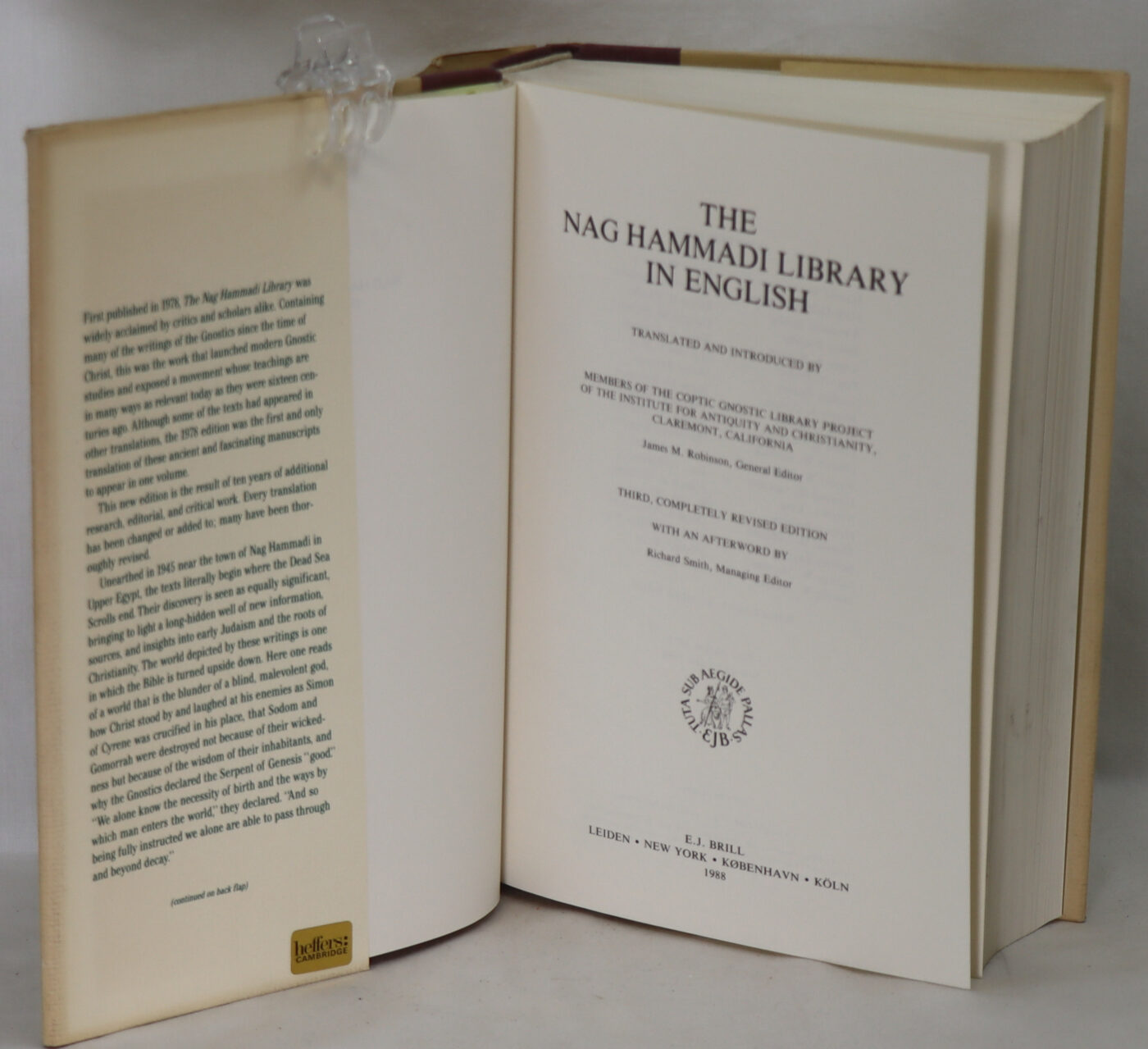

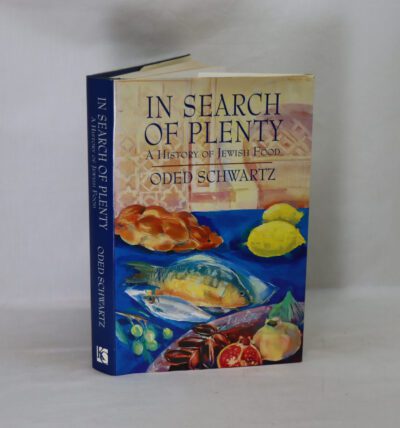

The Nag Hammadi Library in English.

Printed: 1988

Publisher: E J Brill. Leiden

Edition: Revised edition

| Dimensions | 17 × 25 × 5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 17 x 25 x 5

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

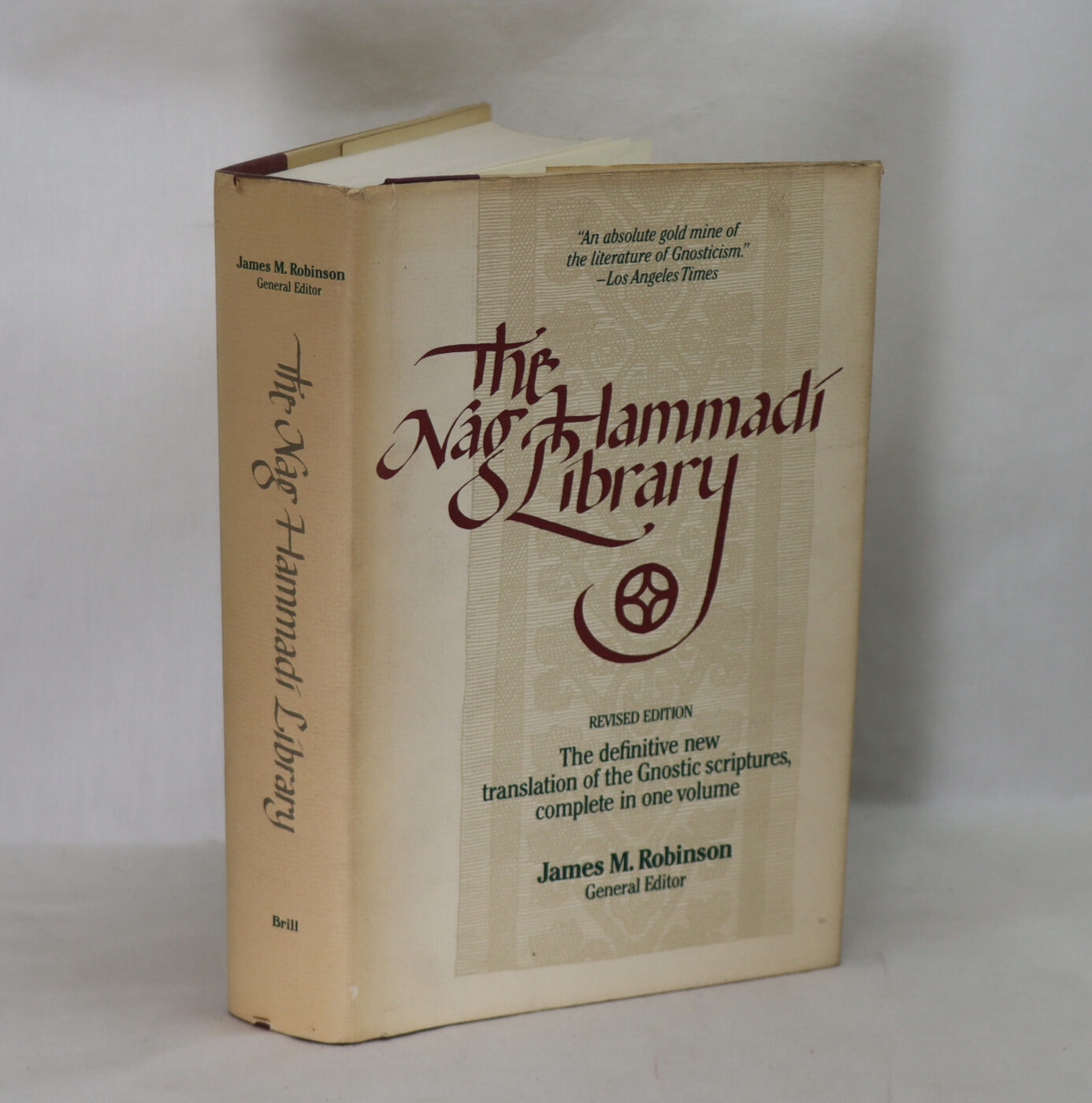

In the original dust jacket. Purple cloth spine with silver title. Beige boards.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

For the near fine condition, please view our photographs. A fantastic copy of the revised Edition. pgs.549, a clean tight copy. The Nag Hammadi library (also known as the Chenoboskion Manuscripts and the Gnostic Gospels) is a collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945. Twelve leather-bound papyrus codices (and a tractate from a thirteenth) buried in a sealed jar were found by an Egyptian farmer named Muhammed al-Samman and others in late 1945. The writings in these codices comprise 52 mostly Gnostic treatises, but they also include three works belonging to the Corpus Hermeticum and a partial translation/alteration of Plato’s Republic. In his introduction to The Nag Hammadi Library in English, James Robinson suggests that these codices may have belonged to a nearby Pachomian monastery and were buried after Saint Athanasius condemned the use of non-canonical books in his Festal Letter of 367 A.D. The Pachomian hypothesis has been further expanded by Lundhaug & Jenott (2015, 2018) and further strengthened by Linjamaa (2024). In his 2024 book, Linjamaa argues that the Nag Hammadi library was used by a small intellectual monastic elite at a Pachomian monastery, and that they were used as a smaller part of a much wider Christian library.

The contents of the codices were written in the Coptic language. The best-known of these works is probably the Gospel of Thomas, of which the Nag Hammadi codices contain the only complete text. After the discovery, scholars recognized that fragments of these sayings attributed to Jesus appeared in manuscripts discovered at Oxyrhynchus in 1898 (P. Oxy. 1), and matching quotations were recognized in other early Christian sources. Most interpreters date the writing of the Gospel of Thomas to the second century, but based on much earlier sources. The buried manuscripts date from the 3rd and 4th centuries. The Nag Hammadi codices are now housed in the Coptic Museum in Cairo, Egypt.

Although the manuscripts discovered at Nag Hammadi are generally dated to the 4th century, there is some debate regarding the original composition of the texts.

-

The Gospel of Thomas is held by most to be the earliest of the “gnostic” gospels composed. Scholars generally date the text to the early to mid-2nd century. The Gospel of Thomas, it is often claimed, has some gnostic elements but lacks the full gnostic cosmology. However, even the description of these elements as “gnostic” is based mainly upon the presupposition that the text as a whole is a “gnostic” gospel, and this idea itself is based upon little other than the fact that it was found along with gnostic texts at Nag Hammadi. Some scholars including Nicholas Perrin argue that Thomas is dependent on the Diatessaron, which was composed shortly after 172 by Tatian in Syria. Others contend for an earlier date, with a minority claiming a date of perhaps 50 AD, citing a relationship to the hypothetical Q document among other reasons.

-

The Gospel of Truth and the teachings of the Pistis Sophia can be approximately dated to the early 2nd century as they were part of the original Valentinian school, though the gospel itself is 3rd century.

-

Documents with a Sethian influence (like the Gospel of Judas, or outright Sethian like Coptic Gospel of the Egyptians) can be dated substantially later than 40 and substantially earlier than 250; most scholars giving them a 2nd-century date. More conservative scholars using the traditional dating method would argue in these cases for the early 3rd century.

-

Some gnostic gospels (for example Trimorphic Protennoia) make use of fully developed Neoplatonism and thus need to be dated after Plotinus in the 3rd century.

James McConkey Robinson (June 30, 1924 – March 22, 2016) was an American scholar who retired as Professor Emeritus of Religion at Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, California, specializing in New Testament Studies and Nag Hammadi Studies. He was a member of the Jesus Seminar and arguably the most prominent Q and Nag Hammadi library scholar of the twentieth century. He was also a major contributor to The International Q Project, acting as an editor for most of their publications. Particularly, he laid the groundwork for John S. Kloppenborg’s foundational work into the compositional history of Q, by arguing its genre as an ancient wisdom collection. He also was the permanent secretary of UNESCO’s International Committee for the Nag Hammadi codices. He is known for his work on the Medinet Madi library, a collection of Coptic Manichaean manuscripts. He has received criticism from philosopher and apologist William Lane Craig regarding his views on Jesus’ resurrection appearances. Robinson argued that these appearances had their origins in second-century Gnosticism. Craig argues that there is no reason to believe that all of these experiences were luminous, and even if they were, that they were interpreted as non-physical appearances.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend