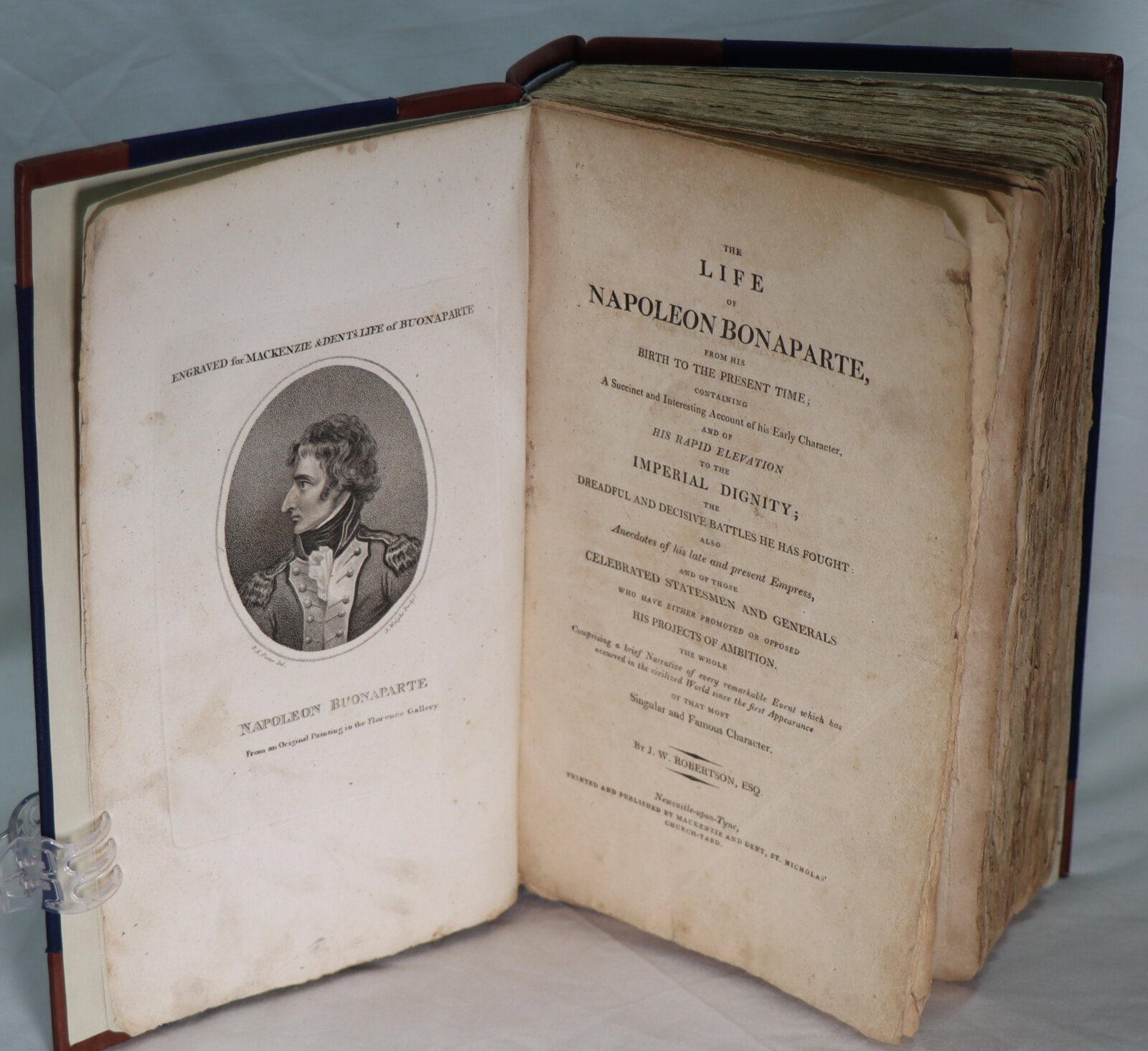

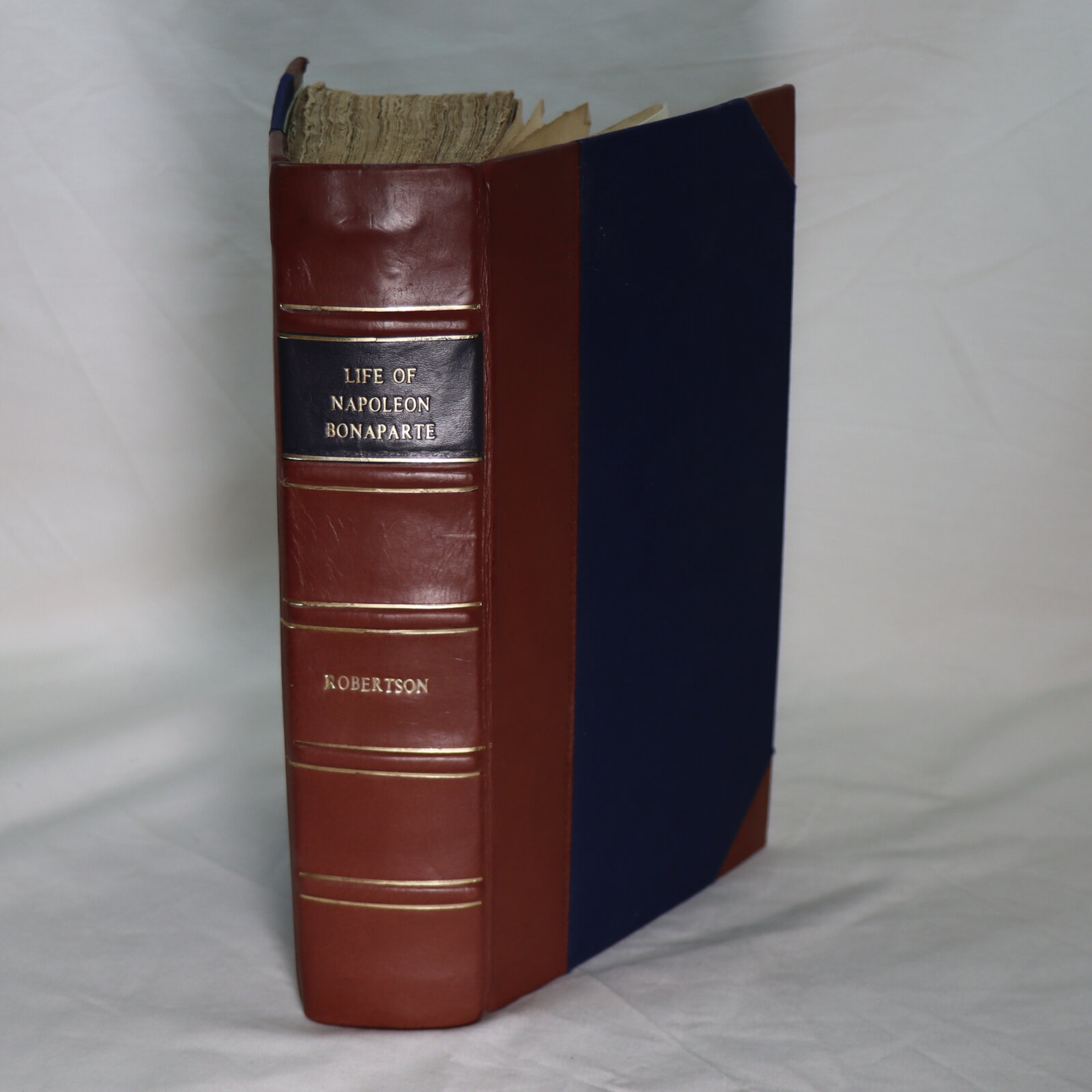

The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte.

By J W Robertson

Printed: 1816

Publisher: Mackenzie & Dent. Newcastle-upon-Tyne

| Dimensions | 15 × 24 × 5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 15 x 24 x 5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

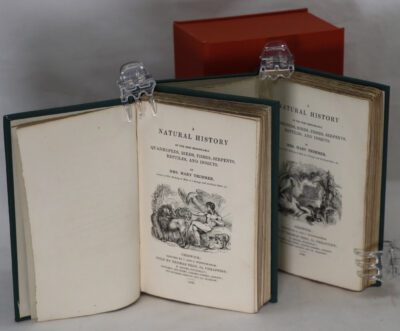

Rebound with brown calf spine, black title plate, gilt banding and title. Navy cloth boards.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Two unique books, fine 1815 & 1816 copy’s superbly rebound by Mr. Brian Cole. There are no others the same. These great works by J W Robertson’s are the first sympathetic Napoleonic editions to be printed in English, both British Newcastle editions were widely plagiarized especially in Delaware, USA where printers based in Wilmington and New Castle churned out thousands of copies to an admiring US public. Nowadays it is forgotten that Britain and the USA had been actively at war since 1812 and that Napoleon in 1803 was responsible for the Louisiana Purchase which doubled the geographic size of the United States. It is also widely not remembered that Newcastle on Tyne was a British literary centre with J W Robertson being a disciple of Dugald Stewart, the Scot with French connections whose input contributed to the US constitution (in 1985 I, Martin Frost, gave Edenside, Dugald Stewart’s estate and Adam Mansion House at Kelso to my first wife for love and affection).

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase totalled 2,144,480 square kilometres (827,987 square miles), doubling the size of the United States.

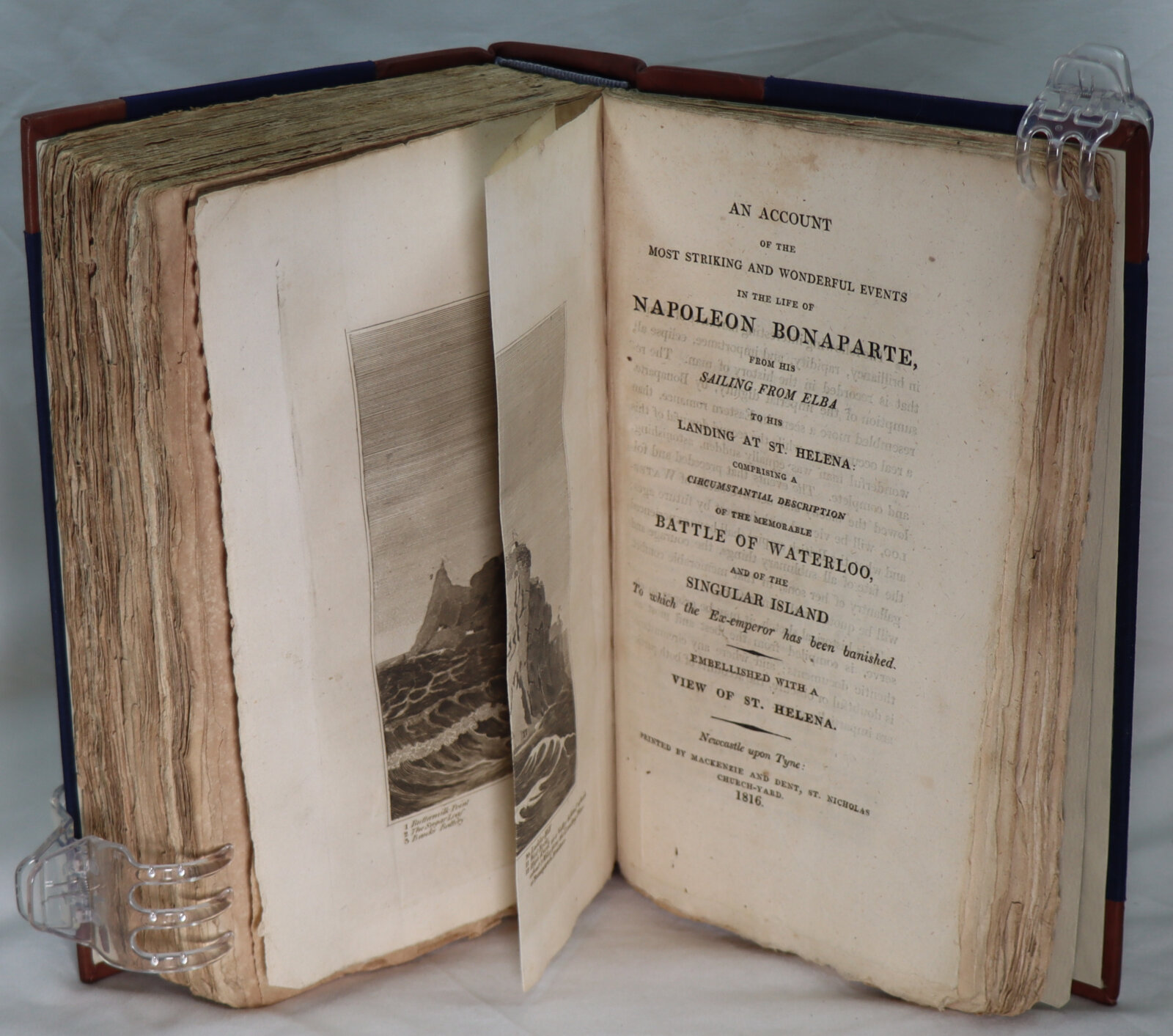

These two books are rebound into one. Hardcover. No marks or writing, clean tight; brown leather spine as per our excellent photographs. One subtitle: Containing a succinct and interesting account of his early character and of his rapid elevation to imperial dignity; second subtitle an account of the most striking and wonderful events in the life of Napoleon Bonaparte from his sailing from Elba to his landing at St. Helena, with fold out etching of the Island of St. Helena dated 1816.

Note: Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of the French, who spent the majority of his life at war against the United Kingdom, became one of the most admired military heroes in British popular culture. For example, in Master Timothy’s Bookcase, G. W. M. Reynolds described him as “the hero of a thousand battles—that meteor which blazed so brightly, and which so long terrified all the nations of the universe with its supernal lustre” (205–06) For a quarter of a century, between 1793 and 1815, Britain had been at war with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, until he was finally defeated at Waterloo. Yet from the moment of his defeat, this great man captivated the British public.

Scene in Plymouth Sound in August 1815: The Bellerophon with Napoleon Aboard at Plymouth (26 July-4 August 1815). John James Chalon (1778-1854). 1817.

When Napoleon surrendered to Captain Maitland in 1815 he was taken to Plymouth aboard HMS Bellerophon. The ship was docked at Plymouth for two weeks with the emperor confined on board. Hundreds of people flocked to the harbour, however, to see if they could catch a glimpse of the great man. The good natured Napoleon relished his new found popularity among the English and made sure he appeared every evening at 6:30 p.m. to wave to his ‘fans’.

Napoleon in Plymouth Sound, August 1815 (Napoleon on Board the Bellerophon at Plymouth). Jules Girardet (1856–1946) 1817. Oil.

Napoleon’s stay at Plymouth was depicted in an 1816 painting by John James Chalon, a Swiss artist working in England, while a later work by the French painter Jules Girardet entitled Napoleon in Plymouth Sound, August 1815 depicted similar scenes of adoring fans clamouring round the Bellerophon in small boats to catch a glimpse of the man. The cordial manner with which the emperor was received by the public led some of the authorities to fear that maybe these throngs of fans were secret revolutionaries. The authorities’ fears were unfounded. Although there were some protests in England in the post-war period, many of which were connected to the campaign for universal male suffrage, very few British radicals would have considered themselves Bonapartist in any sense. Similarly, we find Sir Walter Scott, one of the most celebrated authors of the nineteenth century, writing his nine-volume The Life of Napoleon Buonaparte, Emperor of the French (1827), which, in his own words, was an account of “the most wonderful man and the most extraordinary events of the last thirty years … his splendid personal qualities – his great military actions and political services to France” (I, 1). Upon the book’s first publication, there were some dissenting voices raised against Scott’s depiction of the emperor. These criticisms came from prominent members of the Tory party – a party which boasted among its ranks Napoleon’s conqueror, Duke Wellington. Most of the objections centred upon what Scott’s critics saw as too favourable a gloss on Napoleon’s life. Yet Scott, perhaps anticipating some of his critics, remarked in his preface that Napoleon should be seen for the great man that he was because “the term of hostility is ended when the battle has been won and the foe exists no longer.” Scott’s was obviously a mature and sensible view to take in an era which had witnessed the birth of British nationalism and the denigration of the French in English popular prints. In fact, Scott’s biography of the general did much to cement Napoleon’s posthumous reputation as a great military leader. His biography was reprinted many times throughout the nineteenth century, and to his critics, good-natured as ever, Scott simply responded that “I could have done it better … if I could have written at more leisure, and with a mind more at ease” (Quoted Lockhart IV, 127).

J. G. Lockhart, Walter Scott’s son-in-law and biographer, emulated his relative by writing another much shorter Life of Napoleon (1851), which also was reissued in numerous formats, being abridged for a younger audience as a ‘Gift Edition’ by the publisher, Bickers and Sons in the 1890s. Lockhart praised Napoleon as a man who, although he fought for the wrong side, could be admired for the following reasons: “He recast the art of war … he gave both permanency and breadth to the French Revolution. His reign, short as it was, was sufficient to make it impossible that the offensive privileges of caste should ever be revived in France … he broke down the barriers of custom and prejudice; and revolutionised the spirit of the continent” (495).

The radical, G. W. M. Reynolds, who was enthusiastic about all things French, made Napoleon the hero of a short story entitled “A Tale of the French Revolution,” which appeared in Sherwood’s Monthly Miscellany in 1838, and one of Reynolds’s later novels entitled Pickwick Abroad; or, The Tour in France (1839), a pastiche of Charles Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, includes a sympathetic depiction of the Emperor (49).

Mr. Pickwick Meeting Napoleon from Pickwick Abroad; or, The Tour in France.

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French emperor and military commander who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led successful campaigns during the Revolutionary Wars. He was the leader of the French Republic as First Consul from 1799 to 1804, then of the French Empire as Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814, and briefly again in 1815. His political and cultural legacy endures as a celebrated and controversial leader. He initiated many enduring reforms, but has been criticized for his authoritarian rule. He is considered one of the greatest military commanders in history and his wars and campaigns are still studied at military schools worldwide. However, historians still debate whether he was responsible for the Napoleonic Wars in which between three and six million people died.

Napoleon was born on the island of Corsica into a family descended from Italian nobility. He was resentful of the French monarchy, and supported the French Revolution in 1789 while serving in the French army, trying to spread its ideals to his native Corsica. He rose rapidly in the ranks after saving the governing French Directory by firing on royalist insurgents. In 1796, he began a military campaign against the Austrians and their Italian allies, scoring decisive victories, and became a national hero. Two years later he led a military expedition to Egypt that served as a springboard to political power. He engineered a coup in November 1799 and became First Consul of the Republic. In 1804, to consolidate and expand his power, he crowned himself Emperor of the French.

Differences with the United Kingdom meant France faced the War of the Third Coalition by 1805. Napoleon shattered this coalition with victories in the Ulm campaign and at the Battle of Austerlitz, which led to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1806, the Fourth Coalition took up arms against him. Napoleon defeated Prussia at the battles of Jena and Auerstedt, marched the Grande Armée into Eastern Europe, and defeated the Russians in June 1807 at Friedland, forcing the defeated nations of the Fourth Coalition to accept the Treaties of Tilsit. Two years later, the Austrians challenged the French again during the War of the Fifth Coalition, but Napoleon solidified his grip over Europe after triumphing at the Battle of Wagram.

Hoping to extend the Continental System, his embargo against Britain, Napoleon invaded the Iberian Peninsula and declared his brother Joseph the King of Spain in 1808. The Spanish and the Portuguese revolted in the Peninsular War aided by a British army, culminating in defeat for Napoleon’s marshals. Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia in the summer of 1812. The resulting campaign witnessed the catastrophic retreat of Napoleon’s Grande Armée. In 1813, Prussia and Austria joined Russian forces in a Sixth Coalition against France, resulting in a large coalition army defeating Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig. The coalition invaded France and captured Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate in April 1814. He was exiled to the island of Elba, between Corsica and Italy. In France, the Bourbons were restored to power.

Napoleon escaped in February 1815 and took control of France. The Allies responded by forming a Seventh Coalition, which defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815. The British exiled him to the remote island of Saint Helena in the Atlantic, where he died in 1821 at the age of 51.

Napoleon had a lasting impact on the world, bringing modernizing reforms to France and Western Europe and stimulating the development of nation states. He also sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803, doubling the size of the United States. However, his mixed record on civil rights and exploitation of conquered territories adversely affect his reputation.

In the 1790’s Newcastle was the country’s fourth largest print centre after London, Oxford and Cambridge, and the Literary and Philosophical Society of 1793, with its erudite debates and large stock of books in several languages, predated the London Library by half a century. Some founder members of the Literary and Philosophical Society were abolitionists.

Dugald Stewart FRSE FRS (22 November 1753 – 11 June 1828) was a Scottish philosopher and mathematician. Today regarded as one of the most important figures of the later Scottish Enlightenment, he was renowned as a populariser of the work of Francis Hutcheson and of Adam Smith. Trained in mathematics, medicine and philosophy, his lectures at the University of Edinburgh were widely disseminated by his many influential students. In 1783 he was a joint founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In most contemporary documents he is referred to as Prof Dougal Stewart.

It is by now accepted that James Mill’s History of British India, which exercised such influence over the British image of India and Indians throughout the nineteenth century, was cast in the mould of ‘philosophical history’, the kind of historical writing typical of the Scottish Enlightenment By the 1790s such an approach was faught at Edinburgh by Dugald Stewart, and in Glasgow by John Millar; and their teachings and writings did much to form Mill’s approach, overlaid though it later was by the Benthamite political message. The characteristics of ‘ philosophical history’ can be identified. Writers of the Scottish Enlightenment were concerned to apply to the study of man and society methods of enquiry comparable to those of the natural sciences, and this, for them, involved the formulation of general laws on the basis of observation, and the available evidence about the history, economy, culture, and political institutions of different societies. Certain guidelines were evolved. The starting point was the close interrelationship between all aspects of men’s life within society, between the economy, government, culture, and social life of a people. Secondly, a civilisation, by which was implied all these aspects of a society, could be located on an evolutionary scale, a ladder of civilizations running from ‘rudeness’ to ‘refinement’.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend