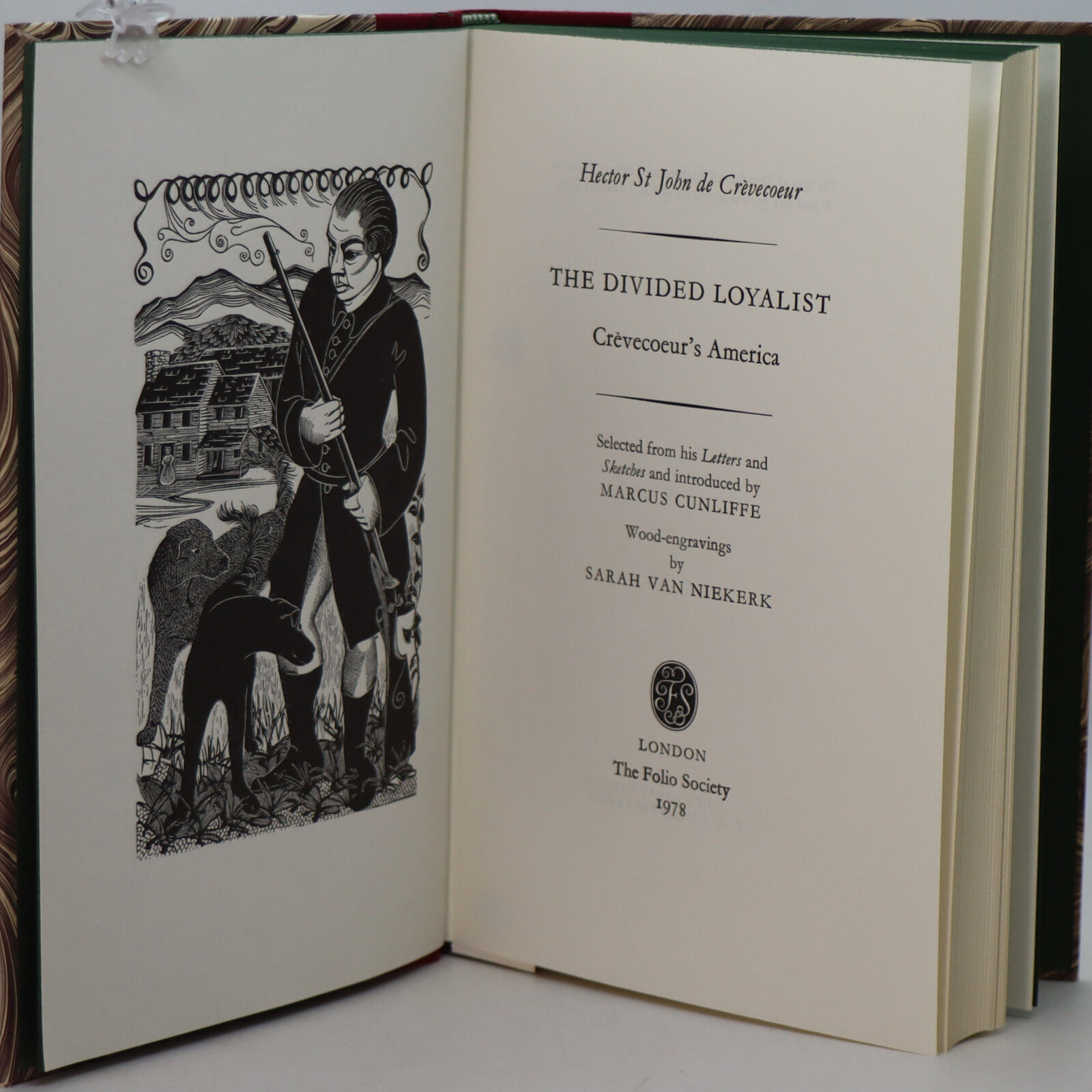

The Divided Loyalist.

By Hector St John Crevecoeur

ISBN: 9780192838988

Printed: 1978

Publisher: The Folio Society. London

| Dimensions | 16 × 24 × 2.5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 16 x 24 x 2.5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

In a fitted box. Maroon cloth spine with gilt title. Red and brown marbled boards.

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Extracts from “Letters from an American Farmer” & “Sketches from 18th century America” by the son of an English settler in Pennsylvania.

Michel Guillaume Jean de Crèvecœur December 31, 1735 – November 12, 1813), naturalized in New York as John Hector St. John, was a French American writer. Crèvecœur was born on December 31, 1735, in Caen, Normandy, France, to the Comte and Comtesse de Crèvecœur (Count and Countess of Crèvecœur). In 1755 he migrated to New France in North America. There, he served in the French and Indian War as a cartographer in the French Colonial Militia, rising to the rank of lieutenant. Following the defeat of the French Army by the British in 1759, he moved to the Province of New York, where he took out citizenship, adopted the English-American name of John Hector St. John, and in 1770 married an American woman, Mehitable Tippet, the daughter of a New York merchant. He bought a sizable farm in the Greycourt area of Chester, NY, a small town in Orange County, New York. He named his farm “Pine Hill” and prospered as a farmer. He also travelled about, working as a surveyor. He started writing about life in the American colonies and the emergence of an American society.

In 1779, during the American Revolution, St. John tried to leave the country to return to France because of the faltering health of his father. Accompanied by his son, he crossed British-American lines to enter British-occupied New York City, where he was imprisoned as an American spy for three months without a hearing. Eventually, he was able to sail for Britain, and was shipwrecked off the coast of Ireland. From Britain, he sailed to France, where he was briefly reunited with his father. After spending some time recovering at the family estate, he visited Paris and the salon of Sophie d’Houdetot.

In 1782, in London, he published a volume of narrative essays entitled Letters from an American Farmer. The book quickly became the first literary success by an American author in Europe and turned Crèvecœur into a celebrated figure. He was the first writer to describe to Europeans – employing many American English terms – the life on the American frontier and to explore the concept of the American Dream, portraying American society as characterized by the principles of equal opportunity and self-determination. His work provided useful information and understanding of the “New World” that helped create an American identity in the minds of Europeans by describing an entire country rather than another regional colony. The writing celebrated American ingenuity and the uncomplicated lifestyle. It described the acceptance of religious diversity in a society being created from a variety of ethnic and cultural backgrounds. His application of the Latin maxim “Ubi panis ibi patria” (Where there is bread, there is my country) to early American settlers also shows an interesting insight. He once praised the middle colonies for “fair cities, substantial villages, extensive fields…decent houses, good roads, orchards, meadows, and bridges, where an hundred years ago all was wild, woody, and uncultivated.”

The original edition, published near the end of the American Revolutionary War, was rather selective in the letters that were included, omitting those that were negative or critical. Norman A. Plotkin argues “it was intended to serve the English Whig cause by fostering an atmosphere conducive to reconciliation.” The book excluded all but one of the letters written after the beginning of the war and also earlier ones that were more critical. Crèvecœur himself sympathized with the Whig cause. His wife’s family remained loyal to the Crown and later fled to Nova Scotia. With regard to French politics, Crèvecœur was a liberal, a follower of the philosophes, and dedicated his book to Abbé Raynal, who he said “viewed these provinces of North America in their true light, as the asylum of freedom; as the cradle of future nations, and the refuge of distressed Europeans.” Plotkin notes that “extremists in the American colonies who violated this principle, incurred Crèvecœur’s harshest criticism, although the severest of these criticisms were considered unsuitable for publication at the time.”

In 1883 his great-grandson, Robert de Crèvecoeur, published a biography for which he used previously unpublished letters and manuscripts passed down by the family. Although it received little notice in France, its existence came to the attention of W. P. Trent of Columbia University, who in 1904 published a reprint of Letters of an American Farmer. In 1916, Crèvecœur’s first American biographer, Julia Post Mitchell, who had access to all the manuscripts, was able to make a more balanced assessment, writing that Crèvecoeur addressed “problems in political economy which European governments were trying in vain to solve.” He was “…illustrating his theories from American conditions,” and was not just “…a garrulous apologist of American life.” The additional manuscripts were published in 1925.

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend