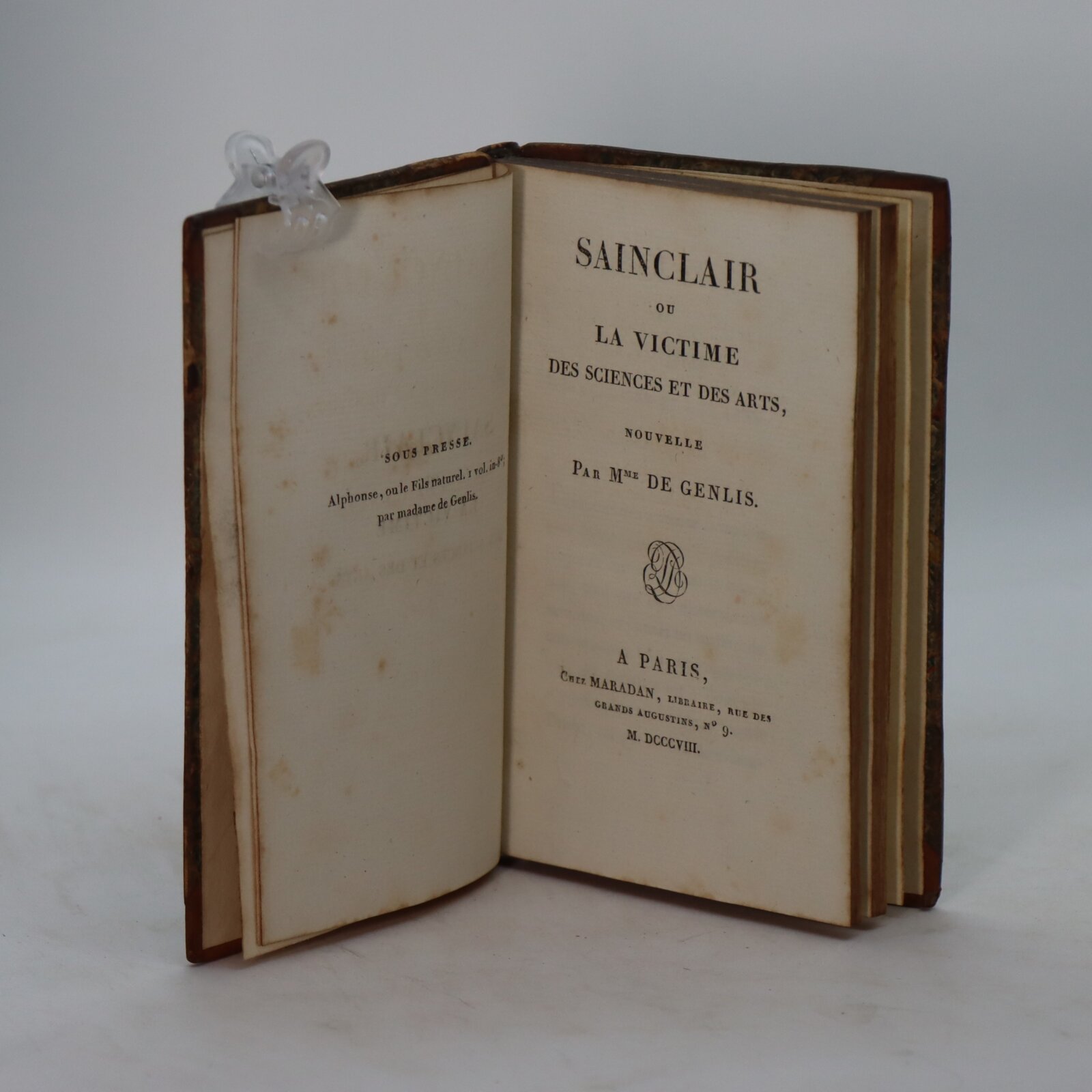

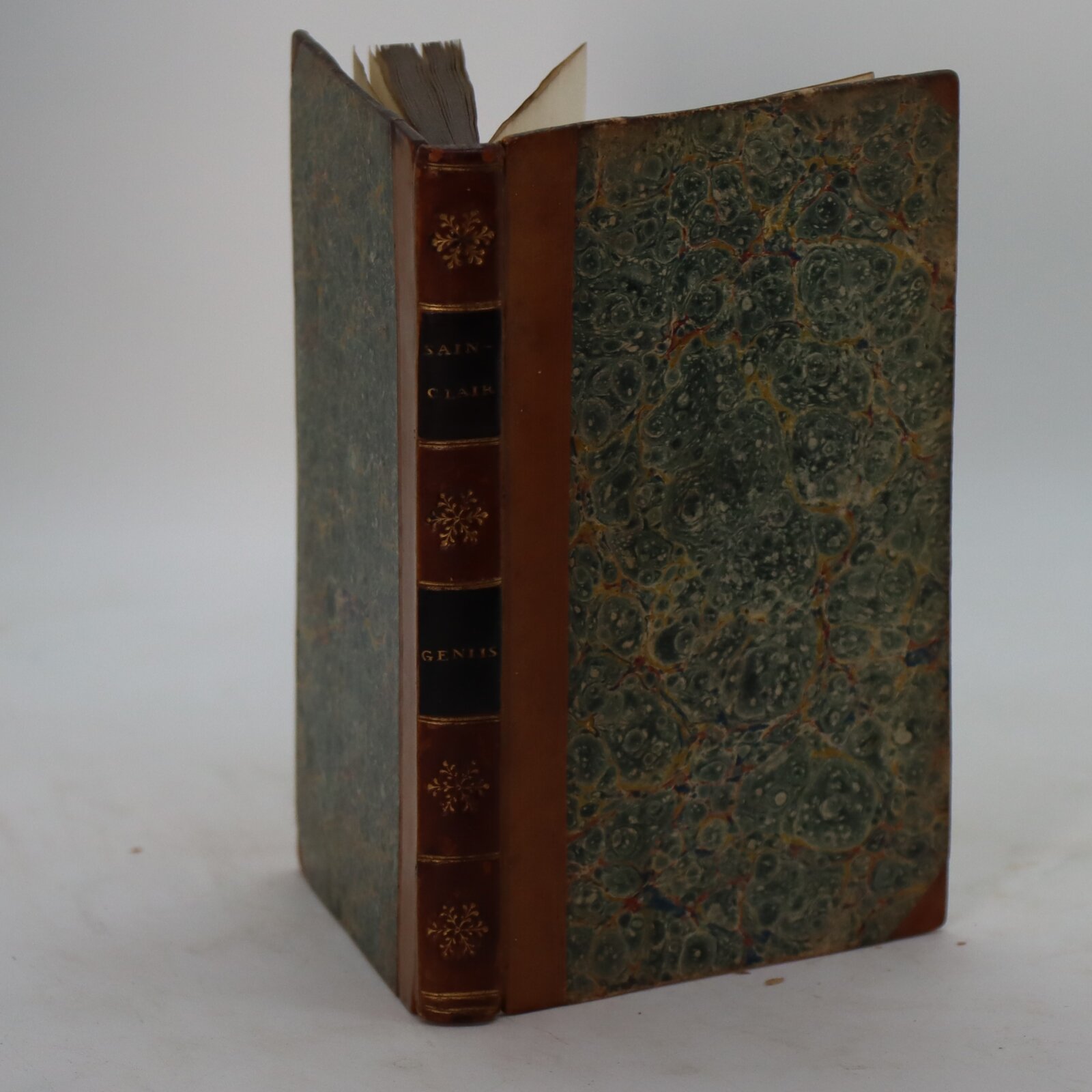

Sainclair. Genlis.

By Mme De Genlis

Printed: 1808

Publisher: Maradan. Paris

| Dimensions | 9 × 14 × 1 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: French

Size (cminches): 9 x 14 x 1

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

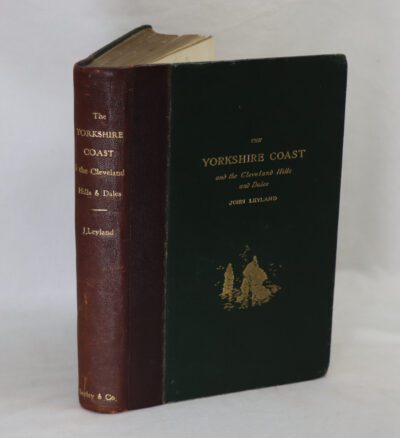

Tan calf spine with green marbled boards. Black title plates with gilt lettering and emblems.

It is the intent of F.B.A. to provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this book offered so to almost stimulate your feel and touch on the book. If requested, more traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

One of her many books: though she is famed for her children’s work, Madame de Genlis had a libertine reputation and she wrote erotica

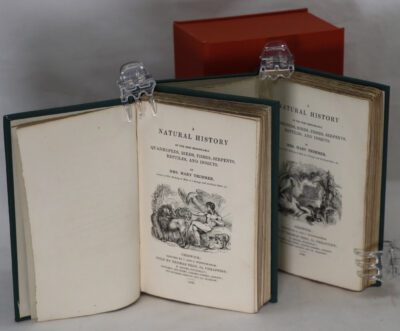

Madame de Genlis wrote many educational ways in which she explained her methods and drew attention to the benefits of practical and observation-based teaching. She herself was a naturalist and observed plants. Thus, the genus of carnivorous plants Genlisea (trap traps) was named after her.

Madame de Genlis was said to have one outstanding talent, it would have been writing. She was a prolific writer, and one person noted she loved it so much ‘she would have invented the inkstand… if the inkstand had been uninvented.’ It was said of her that her pieces were diverse enough to be enjoyed by princes or lackeys and that she “essayed almost every style, from the fugitive piece to the bulky alphabetical compilation, from the roman-poeme to the treatise on domestic economy and the collection of receipts for the kitchen.”

Caroline-Stéphanie-Félicité, Madame de Genlis (25 January 1746 – 31 December 1830) was a French writer of the late 18th and early 19th century, known for her novels and theories of children’s education. She is now best remembered for her journals and the historical perspective they provide on her life and times. In Britain, she was best known for her children’s works, which many welcomed as they presented many of Rousseau’s methods, while attacking his principles. They also avoided libertinism and Roman Catholicism, concepts often associated with the French by the British, who appreciated her innovative educational methods, particularly her morality plays. According to Magdi Wahba, another reason for her popularity was the belief she was as moral as the Baronne d’Almane in Adèle et Théodore. They discovered this was not the case when she fled to London in 1791 but while she lost the esteem of some, including Frances Burney, it had little effect on her book sales.

Jane Austen was familiar with her works, although she returned the novel ‘Alphonsine’ to the Lending Library, claiming it “did not do. We were disgusted in twenty pages, as, independent of a bad translation, it has indelicacies which disgrace a pen hitherto so pure”. However, in Emma her heroine suggests her governess would raise her own daughter the better for having practised upon her, “like La Baronne d’Almane on La Countesse d’Ostalis in Madame de Genlis’ Adelaide and Theodore”. Modern critics claim other themes addressed by Genlis appear in both Emma and Northanger Abbey. Austen continued to read (and lend out) her works however, complaining in 1816 for example that she couldn’t “read Olimpe et Theophile without being in a rage. It is really too bad! – Not allowing them to be happy together when they are married.” Austen’s nieces Anna and Caroline also drew inspiration for their own writings from Madame de Genlis.

British women writers of the late eighteenth century were particularly inspired by Genlis’s novel of education Adèle et Théodore, which Anna Letitia Barbauld compared to Rousseau’s Emile as a type of “preceptive fiction.” Anna Barbauld admired Genlis’s “system of education, the whole of which is given in action” with “infinite ingenuity in the various illustrative incidents.” Clara Reeve described Genlis’s educational program as “the most perfect of any” in Plans of Education (1794), an epistolary work loosely based on Genlis’s novel. Adelaide O’Keeffe’s Dudley(1819) was modeled directly after Genlis’s work, and other texts such as Anna Letitia Barbauld and John Aikin’s Evenings at Home were inspired by Genlis’s Tales of the Castle, a “spin-off” of Adèle et Théodore. As Donelle Ruwe notes, Genlis’s emphasis on the mother as a powerful educating heroine was inspirational, but so too were her books’ demonstrations of how to create homemade literacy objects such as flash cards and other teaching aids.

——————————————–

As gouverneur, Madame de Genlis instituted teaching techniques that were unusual and forward-thinking for the times. For example, history was taught with the help of slides using an early image projector called a magic lantern, and botany studies were conducted by a real botanist while the children went out for their daily walk. Madame de Genlis also believed her students should be self-reliant, sleep on hard beds, and get plenty of exercise. In fact, once she reportedly put lead in the boots of Louis-Philippe, the boy who would grow up to be Louis Philippe I (King of France from 1830 to 1848), and made him walk for miles.

Madame de Genlis was reputedly also a strict taskmaster when it came to learning and education. Her students’ activities began as early as 6.30 in the morning, and the children were kept busy all day. Subjects the children studied included literature, mythology, mathematics, chemistry, geography, physics, and anatomy. Foreign languages were also greatly emphasized, and the children practiced them regularly learning Italian from the chambermaid, German from the gardener, and English from the valet. Yet despite her strictness, her students adored her and sweetly called her ‘Bonne Amie’ or ‘Maman Genlis’.

Madame de Genlis also provided plenty of first-hand experiences and hands-on lessons for her pupils. Field trips were an important part of her curriculum. This resulted in the children visiting a variety of places that included factories, artist studios, and furniture manufacturers. The children also took numerous educational vacations to places such as Normandy, Chantilly, or Spa. Moreover, after the attack by revolutionaries on the Bastille, she took the children to visit the infamous site.

From the garden terrace of her friend Beaumarchais, Mme de Genlis, surrounded by her pupils, watched ‘men, women, and children working with unprecedented ardour’ at the demolition of the fortress…And she shared the joy of the destroyers at the fall of the fortress, on which, so she said, she had never been able to look without a shudder, remembering the arbitrary imprisonments within its walls.

The children’s religious instructions were also not neglected. Madame de Genlis read the Bible to the children faithfully for an hour a day, and when Louis-Philippe was slated to receive his first communion, she undertook to prepare himself for the event. To prepare him, however, she stepped on toes and her pushiness was ‘vociferously protested by the chaplain, l’abbé Guoyt, and seen by many others…as an arrogant usurpation of his theological function.’

Want to know more about this item?

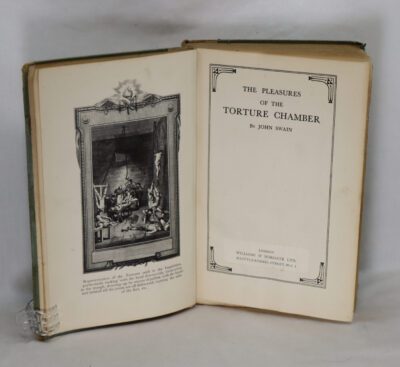

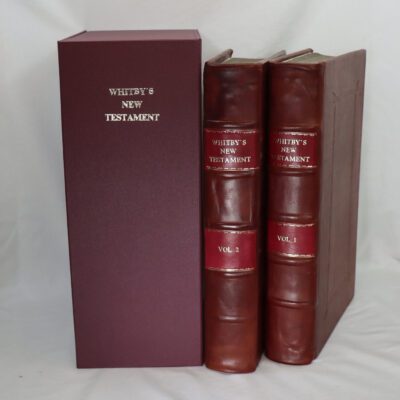

Related products

Share this Page with a friend