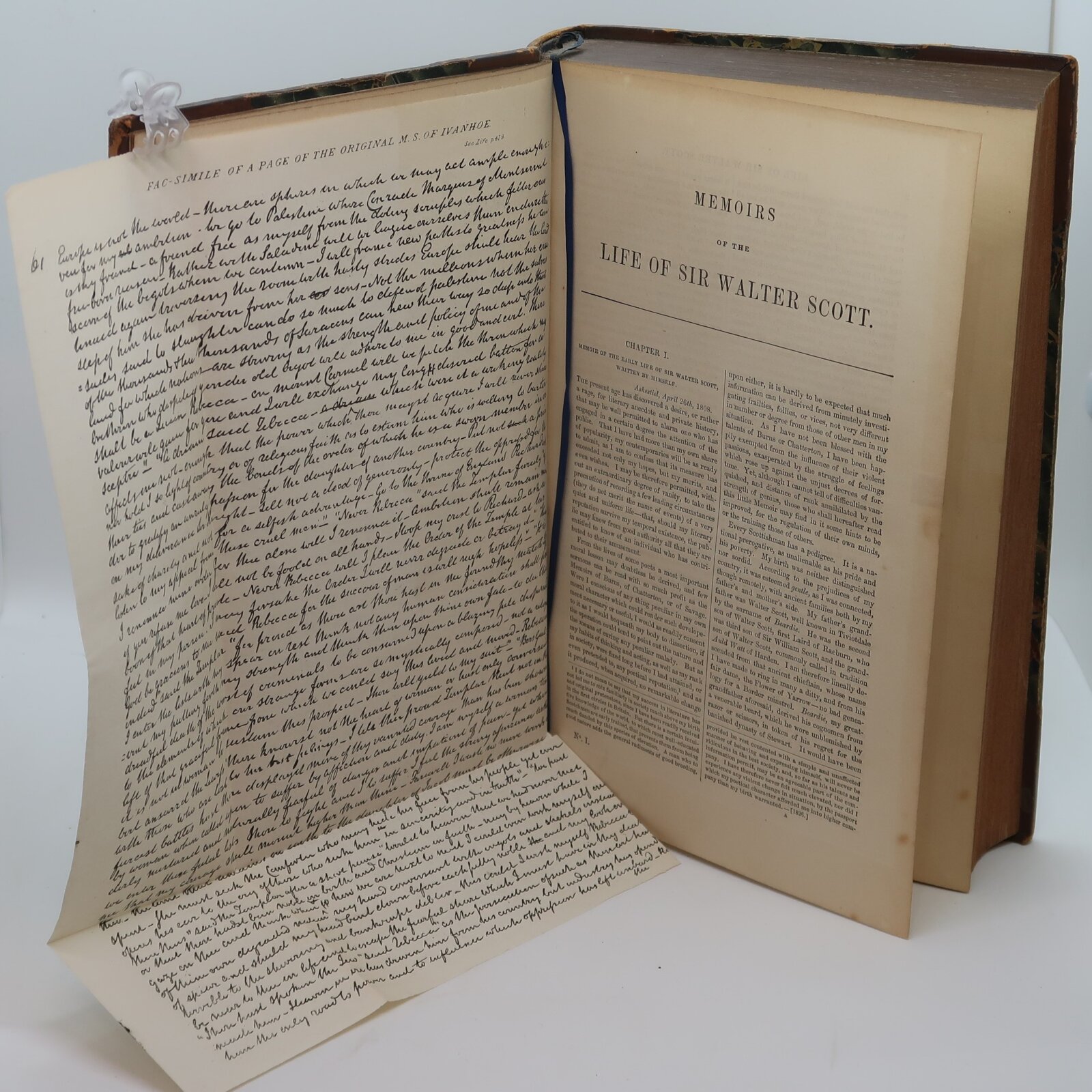

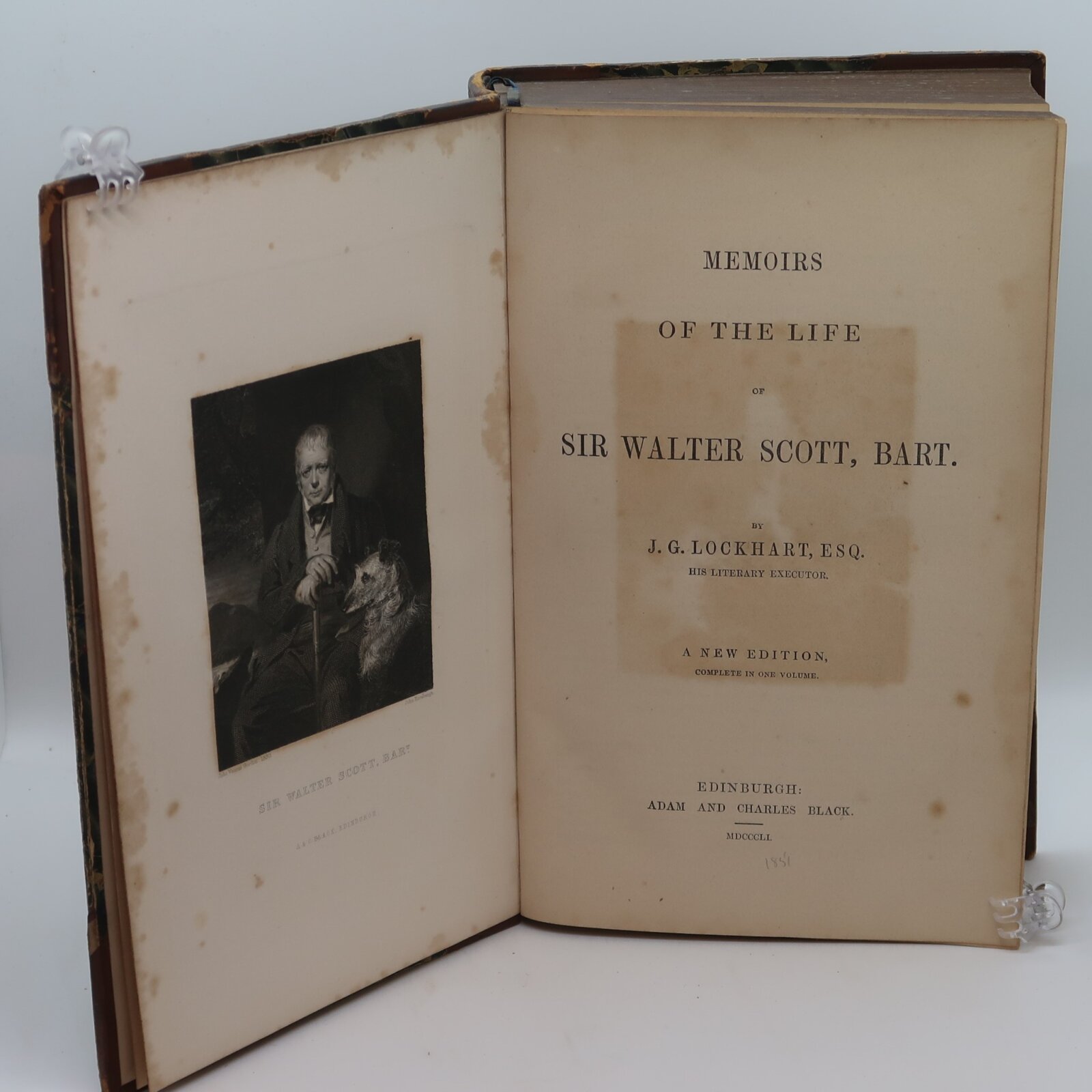

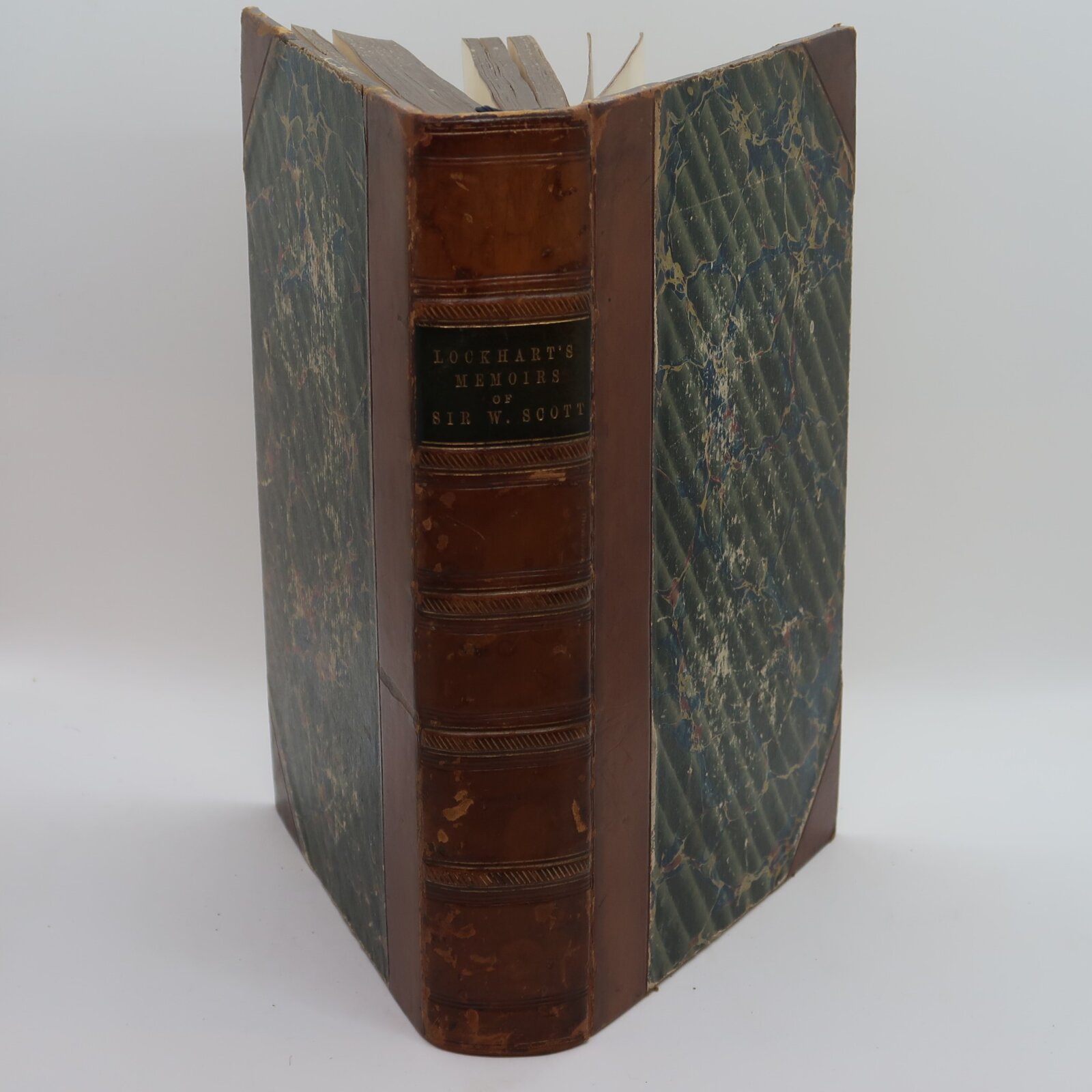

Lockhart's Memoirs of Sir Walter Scott.

By J G Lockhart

Printed: 1851

Publisher: Adam & Charles Black. Edinburgh

Edition: new edition

| Dimensions | 17 × 25 × 5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 17 x 25 x 5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

Tan leather spine with green title plate, gilt banding and title. blue marbled boards.

Lockhart’s major work, and the one for which he is known, is the Life of Sir Walter Scott (7 vols, 1837–1838; 2nd ed., 10 vols., 1839). This biography included the publishing of a great number of Scott’s letters. Thomas Carlyle assessed it in a criticism contributed to the London and Westminster Review (1837). Lockhart’s account of the business transactions between Scott and the Ballantynes and Constable caused an outcry; and in the discussion that followed he showed bitterness in his pamphlet The Ballantyne Humbug handled. The Life of Scott has been called, after Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, the most admirable biography in the English language. The proceeds, which were considerable, Lockhart resigned for the benefit of Scott’s creditors.

John Gibson Lockhart (12 June 1794 – 25 November 1854) was a Scottish writer and editor. He is best known as the author of the seminal, and much-admired, seven-volume biography of his father-in-law Sir Walter Scott: Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart.

In 1818, Lockhart met Sir Walter Scott, who introduced him to his family. Lockhart married Scott’s eldest daughter Sophia in April 1820. It was a happy marriage, with winters spent in Edinburgh and summers at Chiefswood, a cottage on Scott’s Abbotsford estate, where the Lockhart’s first child John Hugh ‘Johnnie’ was born. John Hugh was born with spina bifida and spent much of his time with his grandfather, listening to Scott’s stories about Scottish history, hence Scott’s book Tales of a grandfather. Johnnie died in 1831, at age eleven. A baby girl born to the Lockharts died soon after birth. Sir Walter died in 1832; Sophia died suddenly in 1837, at age 38. Lockhart struggled with the loss of his parents and sister. His third child was Walter Scott Lockhart, who became an army officer, but fell into a bad company, ruined his health, and died in his father’s arms in January 1853 at the age of 26. Lockhart became seriously depressed, almost starving himself to death. He resigned his editorship of the Quarterly Review and spent some time in Italy but returned without recovering his health.

He moved back to Scotland to live with his only surviving child Charlotte, who was settled at Abbotsford with her husband James Hope-Scott. The two had converted to Catholicism, which made for an uncomfortable atmosphere in the home (Charlotte would die in childbirth in 1858, at age 30). Lockhart died a few weeks after his arrival at Abbotsford, on November 25, 1854. He was buried at Dryburgh Abbey, beside his son and father-in-law.

His obituary in The Times, dated December 9, 1854, included the paragraph “Endowed with the very highest order of manly beauty, both of features and expression, he retained the brilliancy of youth and a stately strength of person comparatively unimpaired in ripened life; and then, though sorrow and sickness suddenly brought on a premature old age which none could witness unmoved, yet the beauty of the head and of the bearing so far gained in melancholy loftiness of expression what they lost in animation, that the last phase, whether to the eye of painter or of anxious friend, seemed always the finest.”

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet FRSE FSAScot (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish historical novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, Waverley, Old Mortality, The Heart of Mid-Lothian and The Bride of Lammermoor, and the narrative poems The Lady of the Lake and Marmion. He had a major impact on European and American literature. As an advocate, judge and legal administrator by profession, he combined writing and editing with daily work as Clerk of Session and Sheriff-Depute of Selkirkshire. He was prominent in Edinburgh’s Tory establishment, active in the Highland Society, long a president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1820–1832), and a vice president of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (1827–1829). His knowledge of history and literary facility equipped him to establish the historical novel genre and as an exemplar of European Romanticism. He became a baronet “of Abbotsford in the County of Roxburgh”, Scotland, on 22 April 1820; the title became extinct on his son’s death in 1847.

Although he continued to be extremely popular and widely read, both at home and abroad, Scott’s critical reputation declined in the last half of the 19th century as serious writers turned from romanticism to realism, and Scott began to be regarded as an author suitable for children. This trend accelerated in the 20th century. For example, in his classic study Aspects of the Novel (1927), E. M. Forster harshly criticized Scott’s clumsy and slapdash writing style, “flat” characters, and thin plots. In contrast, the novels of Scott’s contemporary Jane Austen, once appreciated only by the discerning few (including, as it happened, Scott himself) rose steadily in critical esteem, though Austen, as a female writer, was still faulted for her narrow (“feminine”) choice of subject matter, which, unlike Scott, avoided the grand historical themes traditionally viewed as masculine.

Nevertheless, Scott’s importance as an innovator continued to be recognised. He was acclaimed as the inventor of the genre of the modern historical novel (which others trace to Jane Porter, whose work in the genre predates Scott’s) and the inspiration for enormous numbers of imitators and genre writers both in Britain and on the European continent. In the cultural sphere, Scott’s Waverley novels played a significant part in the movement (begun with James Macpherson’s Ossian cycle) in rehabilitating the public perception of the Scottish Highlands and its culture, which had been formerly been viewed by the southern mind as a barbaric breeding ground of hill bandits, religious fanaticism, and Jacobite risings.

Scott served as chairman of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and was also a member of the Royal Celtic Society. His own contribution to the reinvention of Scottish culture was enormous, even though his re-creations of the customs of the Highlands were fanciful at times. Through the medium of Scott’s novels, the violent religious and political conflicts of the country’s recent past could be seen as belonging to history—which Scott defined, as the subtitle of Waverley (“‘Tis Sixty Years Since”) indicates, as something that happened at least 60 years earlier. His advocacy of objectivity and moderation and his strong repudiation of political violence on either side also had a strong, though unspoken, contemporary resonance in an era when many conservative English speakers lived in mortal fear of a revolution in the French style on British soil. Scott’s orchestration of King George IV’s visit to Scotland, in 1822, was a pivotal event intended to inspire a view of his home country that, in his view, accentuated the positive aspects of the past while allowing the age of quasi-medieval blood-letting to be put to rest, while envisioning a more useful, peaceful future.

After Scott’s work had been essentially unstudied for many decades, a revival of critical interest began in the middle of the 20th century. While F. R. Leavis had disdained Scott, seeing him as a thoroughly bad novelist and a thoroughly bad influence (The Great Tradition [1948]), György Lukács (The Historical Novel [1937, trans. 1962]) and David Daiches (Scott’s Achievement as a Novelist [1951]) offered a Marxian political reading of Scott’s fiction that generated a great deal of genuine interest in his work. These were followed in 1966 by a major thematic analysis covering most of the novels by Francis R. Hart (Scott’s Novels: The Plotting of Historic Survival). Scott has proved particularly responsive to Postmodern approaches, most notably to the concept of the interplay of multiple voices highlighted by Mikhail Bakhtin, as suggested by the title of the volume with selected papers from the Fourth International Scott Conference held in Edinburgh in 1991, Scott in Carnival. Scott is now increasingly recognised not only as the principal inventor of the historical novel and a key figure in the development of Scottish and world literature, but also as a writer of a depth and subtlety who challenges his readers as well as entertaining them.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend