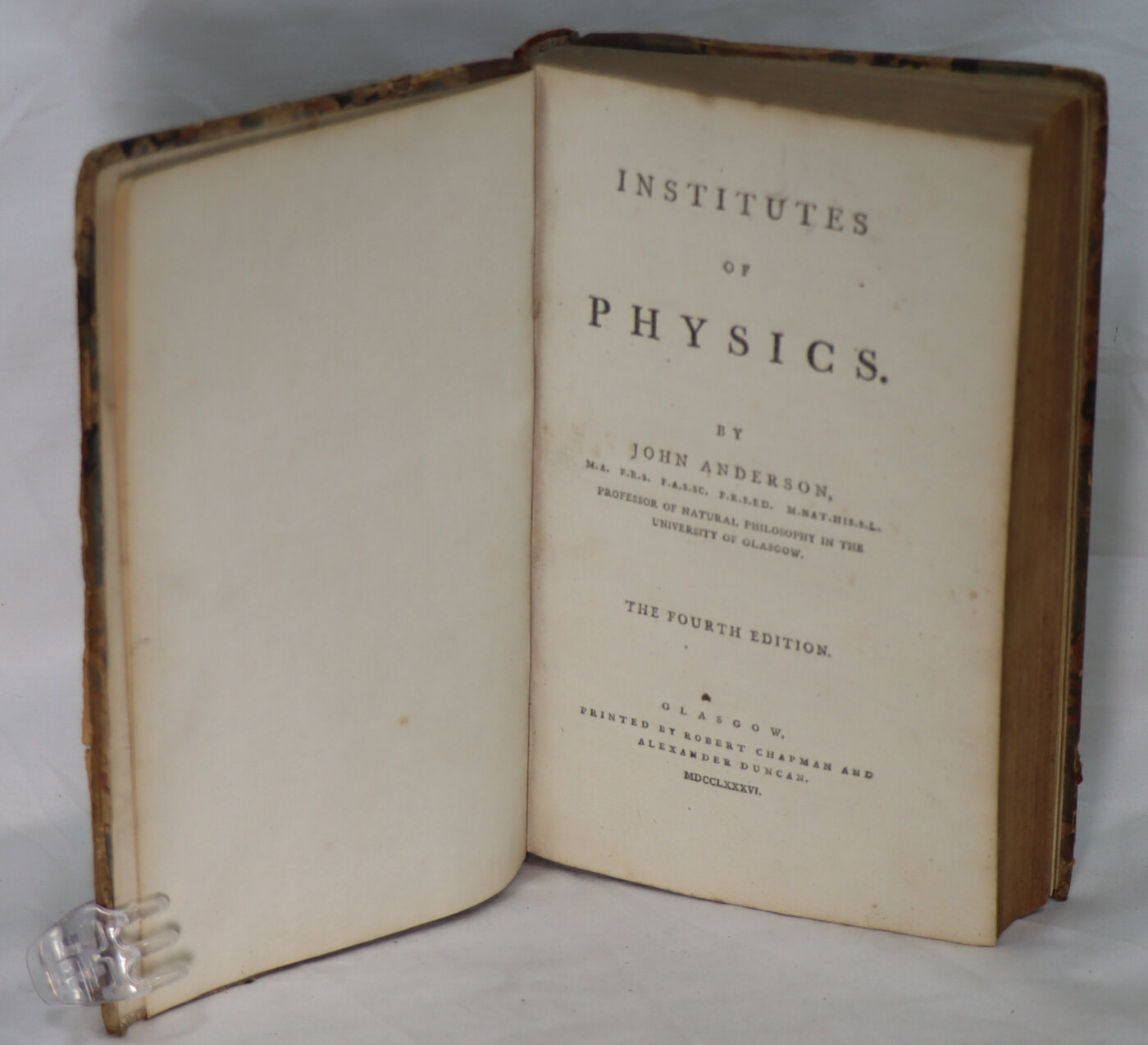

Institutes of Physics.

By John Anderson

Printed: 1786

Publisher: University of Glasgow. Glasgow

Edition: Fourth edition

| Dimensions | 14 × 21 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 14 x 21 x 3

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

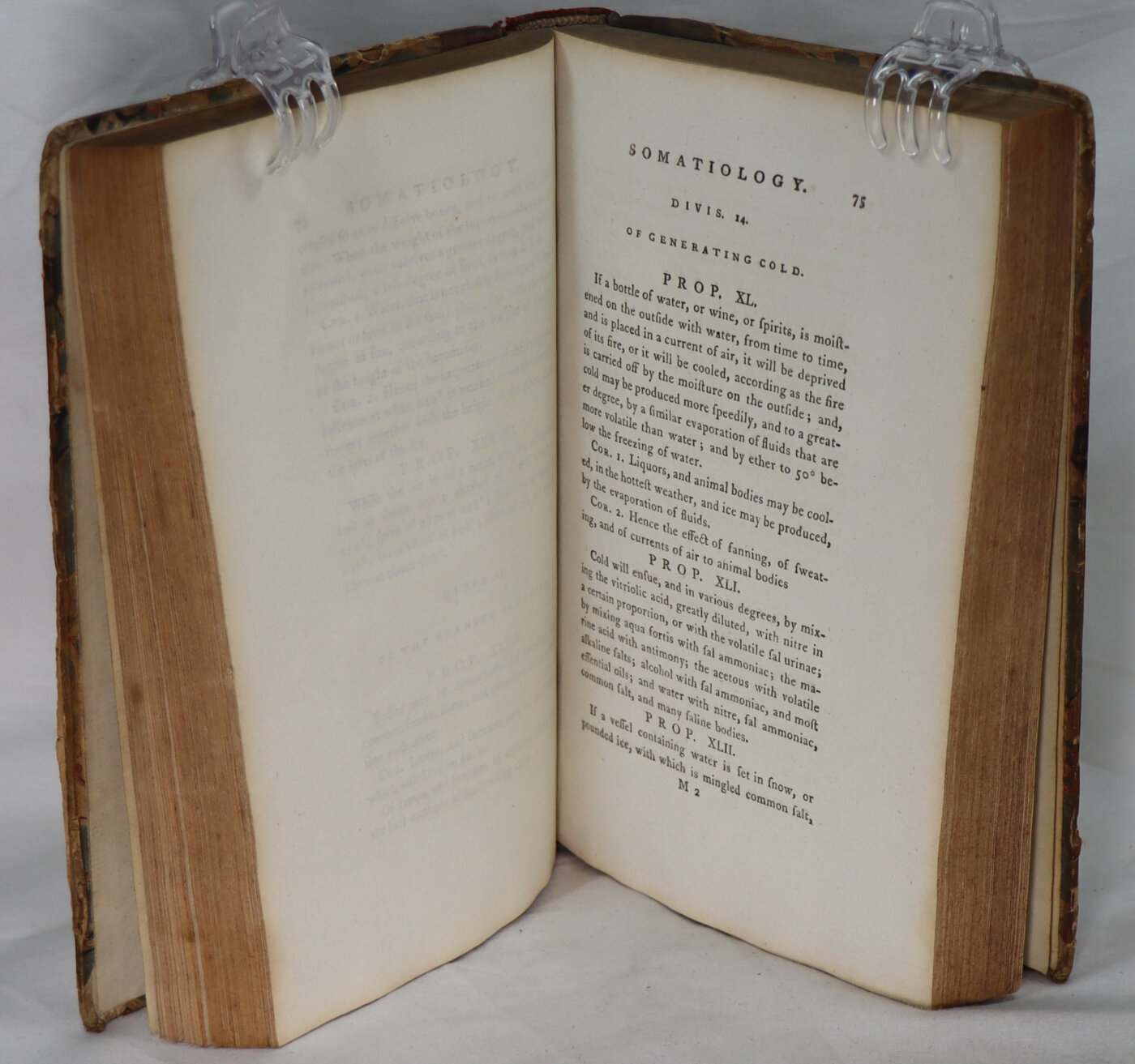

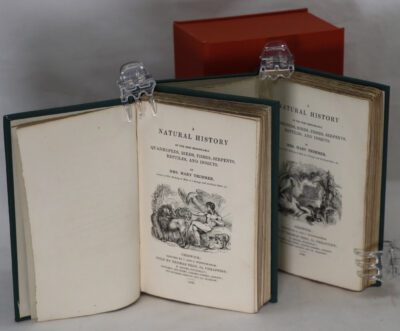

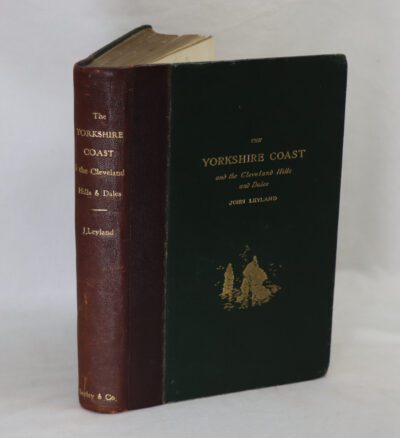

Tan calf spine with gilt banding. Title plate missing. Blue and tan marbled boards.

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

Note: This book carries the £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list.

£139.00

A lovely and very well kept example of this famous book. View the pictures and see for yourself the quality of this fine book.

John Anderson FRSE FRS FSAScot (26 September 1726 – 13 January 1796) was a Scottish natural philosopher and liberal educator at the forefront of the application of science to technology in the industrial revolution, and of the education and advancement of working men and women. He was a joint founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and was the posthumous founder of Anderson’s College (later Anderson’s Institution), which ultimately evolved into the University of Strathclyde.

Anderson was born at the manse at Rosneath, Dunbartonshire, the son of Margaret Turner (d. 1784) and Rev James Anderson. His father and grandfather were prominent ministers of the church. After his father’s death he was raised by his aunt in Stirling, where he attended grammar school.

He graduated with an MA from the University of Glasgow in 1745.

During the Jacobite Rising of 1745 he served as an officer in the Hanoverian Army.

From 1755-57 he was Professor of Ecclesiastical History in the University of Glasgow, and from 1757 to 1796 Professor of Natural Philosophy. He is the longest-serving natural philosophy lecturer during the 18th century.

In 1760, Anderson was appointed to the more congenial post of professor of natural philosophy at the University of Glasgow. He began to concentrate on physics. He had a love of experiments, practical mechanics and inventions. He encouraged James Watt in his development of steam power. He was acquainted with Benjamin Franklin, and in 1772 he installed the first lightning conductor in Glasgow.

Anderson also wrote the pioneering textbook Institutes of Physics published in 1786, which went through five editions in ten years. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and this brought him into contact with many of the leading scientists of the day.

A pioneer of vocational education for working people. His greatest love though was in providing “useful learning” to the working class, especially in the application of science to industry. He did this alongside his University duties, by providing non-academic lectures for artisans during the evenings. In these popular lectures he concentrated on experiments and demonstrations, and from his predilection for setting off explosions and fireworks, he acquired the nickname “Jolly Jack Phosphorus”.

Radical politics: Anderson was also known for his radical political views and was a supporter of the French Revolution. In 1791 he invented a new type of six-pound gun, which was presented to the National Convention in Paris as “the gift of Science to Liberty”. While he was in France, neighbouring Germany, fearing the spread of radical politics to its territory, imposed a blockade on French newspapers. Anderson suggested sending pamphlets on the wind to Germany attached to small hydrogen balloons, and this was done, with each balloon bearing an inscription translated as “O’er hills and dales, and lines of hostile troops, I float majestic, bearing the laws of God and Nature to oppressed men, and bidding them with arms their rights maintain.”

Founder of a university: Building on the lectures for artisans, he bequeathed his property for the foundation of a school in Glasgow devoted to “useful learning”, called Anderson’s Institution or Andersonian University. As an example of its success it enabled a young millworker, David Livingstone, to become a famous missionary doctor and the foremost explorer of his day. The Institution underwent various name-changes and a number of mergers with other colleges before arriving at its current form as the University of Strathclyde, which honours Anderson in the name of the physics building and the main library, the Andersonian Library. The city centre campus is named the John Anderson Campus.

John Anderson died in Glasgow at the age of 69.

He is buried with his grandfather in Ramshorn Cemetery on Ingram Street in Glasgow. On 13 January 1996 representatives from the University of Glasgow laid a wreath to mark the bicentennial of Anderson’s death.

—————————————–

In 1788, the American statesman and scientist, Benjamin Franklin, returned to spend his last years at home in Philadelphia. Franklin was afflicted with ‘the Gout and Stone’, which caused him to largely withdraw from public life until his death in 1790. However, he endeavored to keep up his correspondence, and managed to reply to a letter he received in February 1788 from Mr John Anderson of Glasgow College. This letter (ref: GB 249/OA/2/6) is our featured item for September, as this month the University of Strathclyde will be visited by the ‘Friends of Franklin’ from Philadelphia, who are touring Scotland in Franklin’s footsteps.

Benjamin Franklin came to Scotland twice, in 1759 and 1771. He was especially keen to visit the country’s seats of learning, and on both occasions he spent time with the Professor of Natural Philosophy at Glasgow College, John Anderson. In 1759, Anderson accompanied Franklin on a trip to Dunkeld, Perth and St Andrews, where Franklin was presented with an honorary diploma. During this journey, the gentlemen probably had much to discuss in the field of natural philosophy, for Anderson must have been fascinated by his fellow scientist’s experiments with electricity and lightning.

But Anderson and Franklin had a great deal more in common, as they shared a concern for the dissemination of useful and practical knowledge. Franklin’s efforts in this regard, which culminated in the creation of the University of Pennsylvania, had commenced in 1749 with the publication of his paper ‘Proposals for the Education of Youth in Pennsylvania’, in which he argued:

“As to their Studies, it would be well if they could be taught ever[y] Thing that is useful, and ever[y] Thing that is ornamental: But Art is long, and their Time is short. It is therefore propos’d that they learn those Things that are likely to be most useful and most ornamental. Regard being had to the several Professions for which they are intended.”

Franklin’s radical proposal to deliver a more practical and useful form of education is still espoused by the modern day University of Pennsylvania.

Franklin’s example may have inspired John Anderson to set up his ‘anti-toga’ classes for the working men and women of Glasgow, and to leave instructions in his Will for the foundation of a new educational establishment after his death. In 1796, Anderson’s Institution was duly established by his trustees, and has evolved into the present day University of Strathclyde. This excerpt from the Will echoes Franklin’s own proposals for Pennsylvania, with Anderson envisaging that

“…from these small beginnings, this institution may become a seminary of Sound Religion; Useful Learning; and Liberality of Sentiment.”

To this day, Strathclyde remains guided by Anderson’s concept of a ‘place of useful learning’.

When Franklin returned to Scotland in 1771, he again visited John Anderson, who gave him a tour of the Glasgow College lecture halls and experimental laboratories. As they progressed from room to room, they most likely discussed Anderson’s plans to erect a lightning conductor on the College building, both to protect the building and to facilitate electrical experiments. The conductor was erected on the College steeple in 1772 and was the first of its kind in Glasgow. Anderson’s personal collection of books – which he bequeathed to form the original library of Anderson’s Institution – includes a fairly comprehensive section on eighteenth-century natural philosophy and electricity.

In 1786, Anderson published the first complete edition of his Institutes of Physics. He enclosed a copy of this work when he wrote to Franklin in February 1788, believing that it “may amuse you; and be [of] use to some young Lecturer in Philadelphia: for, from the experience of thirty years, I am convinced that the plan is good…” Anderson’s letter also comments on the second volume of Sir John Dalrymple’s Memoirs [of Great Britain and Ireland], and gives his opinion on carronades.

Franklin’s reply to the letter is brief, but he declared himself “much pleased with your Institutes [of Physics]; and I think your Remarks on the History [Dalrymple’s Memoirs of Great Britain and Ireland] are just”. It is a testament to their enduring friendship and to Anderson’s warm hospitality that Franklin personally replied to Anderson, despite his failing health. Though often viewed as an eccentric, meddlesome character, John Anderson was clearly an inspirational teacher – a quality prized and encouraged by Benjamin Franklin.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend