Holbein's Dance of Death.

By John Holbein

Printed: 1803

Publisher: John Scott & Thomas Ostell. London

Language: English, French

Size (cminches): 17 x 20 x 2.5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Item information

Description

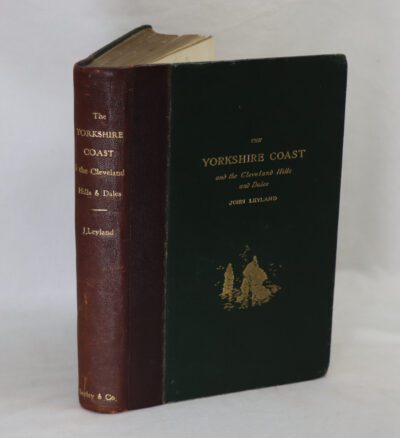

Red leather binding with raised banding, gilt decoration and title on the spine. Gilt ‘Cambridge panel’ on the boards.

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

Note: This book carries the £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list.

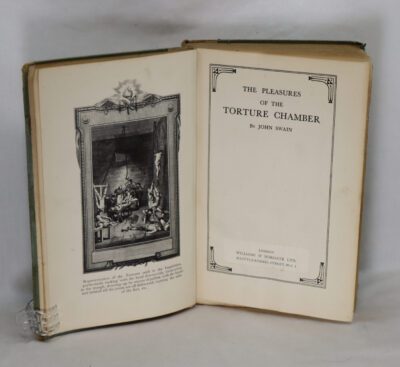

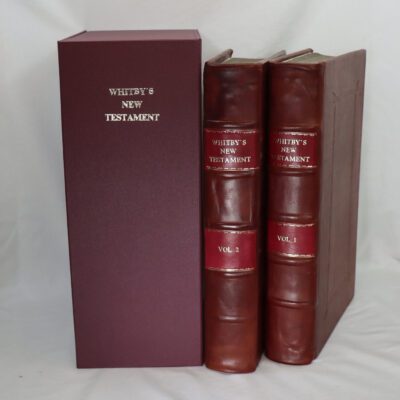

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. “Descriptions of each plate in French and English, with the Scripture Text from which the designs were taken. Printed by W. Smith and Co. King Street, Seven Dials, for John Scott, No. 447, Strand: & Thomas Ostell, No. 3, Ave Maria Lane 1803”. Engraved frontispiece, engraved title, engraved portrait of Holbein. Full leather cover with embossed design and gilt decoration. This is a very hard to find rare book.

Note: this book is lovingly reset in its original papers by the expert bookbinder, Brian Cole. It is again in fantastic condition which ought to see out a further two hundred years.

The Dance of Death (1493) by Michael Wolgemut, from the Nuremberg Chronicle of Hartmann Schedel

The Danse Macabre, also called the Dance of Death, is an artistic genre of allegory from the Late Middle Ages on the universality of death.

The Danse Macabre consists of the dead, or a personification of death, summoning representatives from all walks of life to dance along to the grave, typically with a pope, emperor, king, child, and laborer. The effect is both frivolous and terrifying, beseeching its audience to react emotionally. It was produced as memento mori, to remind people of the fragility of their lives and how vain the glories of earthly life. Its origins are postulated from illustrated sermon texts; the earliest recorded visual scheme (apart from 14th century Triumph of Death paintings) was a now-lost mural at Holy Innocents’ Cemetery in Paris dating from 1424 to 1425.

Hans Holbein the Younger (Hans Holbein der Jüngere; c. 1497 – between 7 October and 29 November 1543) was a German-Swiss painter and printmaker who worked in a Northern Renaissance style, and is considered one of the greatest portraitists of the 16th century. He also produced religious art, satire, and Reformation propaganda, and he made a significant contribution to the history of book design. He is called “the Younger” to distinguish him from his father Hans Holbein the Elder, an accomplished painter of the Late Gothic school.

Holbein was born in Augsburg but worked mainly in Basel as a young artist. At first, he painted murals and religious works, and designed stained glass windows and illustrations for books from the printer Johann Froben. He also painted an occasional portrait, making his international mark with portraits of humanist Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam. When the Reformation reached Basel, Holbein worked for reformist clients while continuing to serve traditional religious patrons. His Late Gothic style was enriched by artistic trends in Italy, France, and the Netherlands, as well as by Renaissance humanism. The result was a combined aesthetic uniquely his own.

Holbein travelled to England in 1526 in search of work with a recommendation from Erasmus. He was welcomed into the humanist circle of Thomas More, where he quickly built a high reputation. He returned to Basel for four years, then resumed his career in England in 1532 under the patronage of Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell. By 1535, he was King’s Painter to Henry VIII of England. In this role, he produced portraits and festive decorations, as well as designs for jewellery, plate, and other precious objects. His portraits of the royal family and nobles are a record of the court in the years when Henry was asserting his supremacy over the Church of England.

Holbein’s art was prized from early in his career. French poet and reformer Nicholas Bourbon (the elder) dubbed him “the Apelles of our time”, a typical accolade at the time. Holbein has also been described as a great “one-off” in art history since he founded no school. Some of his work was lost after his death, but much was collected and he was recognized among the great portrait masters by the 19th century. Recent exhibitions have also highlighted his versatility. He created designs ranging from intricate jewellery to monumental frescoes.

Holbein’s art has sometimes been called realist, since he drew and painted with a rare precision. His portraits were renowned in their time for their likeness, and it is through his eyes that many famous figures of his day are pictured today, such as Erasmus and More. He was never content with outward appearance, however; he embedded layers of symbolism, allusion, and paradox in his art, to the lasting fascination of scholars. In the view of art historian Ellis Waterhouse, his portraiture “remains unsurpassed for sureness and economy of statement, penetration into character, and a combined richness and purity of style’.

Renowned for his Dance of Death series, the famous designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543) were drawn in 1526 while he was in Basel. They were cut in wood by the accomplished Formschneider (block cutter) Hans Lützelburger.

William Ivins (quoting W. J. Linton) writes of Lützelburger’s work wrote:

“‘Nothing indeed, by knife or by graver, is of higher quality than this man’s doing.’ For by common acclaim the originals are technically the most marvelous woodcuts ever made.”

These woodcuts soon appeared in proofs with titles in German. The first book edition, containing forty-one woodcuts, was published at Lyons by the Treschsel brothers in 1538. The popularity of the work, and the currency of its message, are underscored by the fact that there were eleven editions before 1562, and over the sixteenth century perhaps as many as a hundred unauthorized editions and imitations. Ten further designs were added in later editions.

The Dance of Death (1523–26) refashions the late-medieval allegory of the Danse Macabre as a reformist satire, and one can see the beginnings of a gradual shift from traditional to reformed Christianity. That shift had many permutations however, and in a study Natalie Zemon Davis has shown that the contemporary reception and afterlife of Holbein’s designs lent themselves to neither purely Catholic or Protestant doctrine, but could be outfitted with different surrounding prefaces and sermons as printers and writers of different political and religious leanings took them up. Most importantly, “The pictures and the Bible quotations above them were the main attractions […] Both Catholics and Protestants wished, through the pictures, to turn men’s thoughts to a Christian preparation for death.“.

The 1538 edition which contained Latin quotations from the Bible above Holbein’s designs, and a French quatrain below composed by Gilles Corrozet (1510–1568) actually did not credit Holbein as the artist. It bore the title: Les simulachres & / HISTORIEES FACES / DE LA MORT, AUTANT ELE/gammēt pourtraictes, que artifi/ciellement imaginées. / A Lyon. / Soubz l’escu de COLOIGNE. / M.D. XXXVIII. (“Images and Illustrated facets of Death, as elegantly depicted as they are artfully conceived.”) These images and workings of death as captured in the phrase “histories faces” of the title “are the particular exemplification of the way death works, the individual scenes in which the lessons of mortality are brought home to people of every station.”

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend