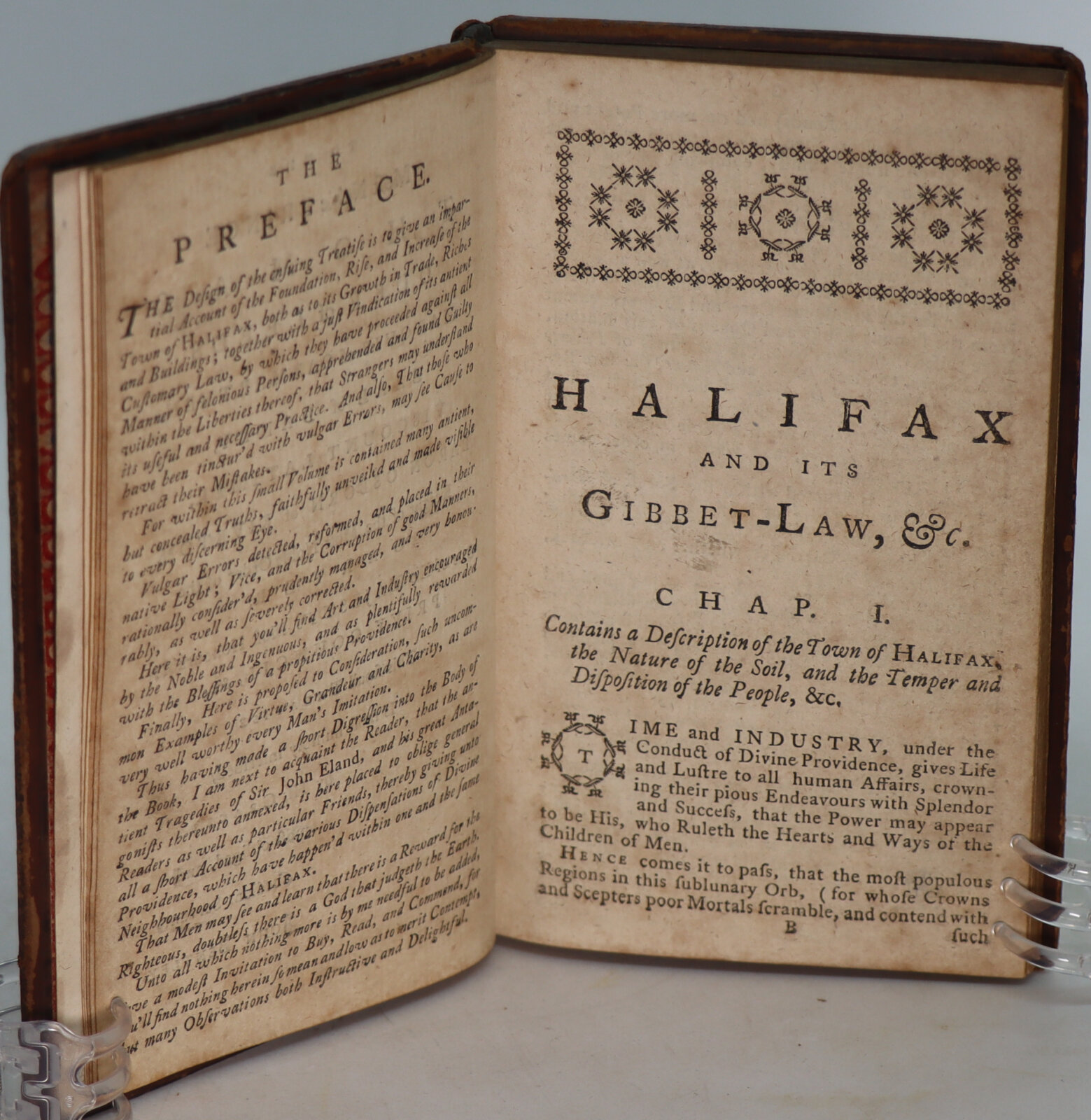

Halifax and it's Gibbet-Law.

By B Boothroyd

Printed: circa 1780

Publisher: B Boothroyd. Pontefract

| Dimensions | 10 × 16 × 1 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 10 x 16 x 1

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Your items

Item information

Description

Brown calf binding with tan title plate, gilt banding. decoration and title on the spine . Gilt decorative edging on the boards.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Believed to be one of earliest renditions of this most famous book, published after 1761. Condition: Very Good. An engraved frontispiece depicting the town and its gibbet, some uniform light browning to the paper throughout, Title page to first part has no date of publication, second part dated 1761 and includes ‘A Short but Full Account of the Lives and Deaths of Wilkin Lockwood and Adam Beaumont, Esqs, and what Travels and Adventures happened unto them after the Battle with Eland Men in Anely Wood, as the same is Recorded in a very Ancient Manuscript’. Bound in contemporary full tree calf with gilt decoration to boards, spine with gilt decoration.

This book was first published in 1708. According to Upcott the author was a physician named Dr. Samuel Midgley, “who wrote it… while in Halifax jail for debt, where he died in 1695. His poverty prevented his printing it; and John Bentley (under whose name the volume is generally known), who was Clerk of Halifax Church, claimed the honour of it after his death.” Chapter I contains a description of town customs and traditions; chapter II discusses the laws of Halifax and defends the Gibbet Law which states that any felon caught with stolen commodities valued at thirteen pence half-penny shall, following his condemnation, be led to the town gibbet and have his head cut off; chapter III offers a narrative of trying felons in Halifax. The second part of the book contains a separate title page “Revenge upon revenge: or, an historical narrative of the tragical practices of Sir John Eland, of Eland, High Sheriff of the County of York…” (Halifax, 1761), which recounts some of the misdeeds surrounding the “Elland Feud,” particularly the murder of Sir Robert Beaumont by Sir John Eland and the subsequent killing of Eland by Beaumont s son.

Halifax was also a part of the manor of Wakefield. The lord of the manor of Wakefield had certain long-held privileges that gave him the right to have thieves that stole 13 1/2d and over executed.

Around 100 people were executed by this law and 53 of them were executed by the gibbet. The Halifax gibbet looked very similar to the French guillotine apart from the blade which was axe-shaped instead of triangular. It was also never sharpened which meant it relied on the weight and drop to sever the head by tearing.

Dr. Samuel Midgley (16?? – 1695), a physician of Luddenden. He was continually in prison for debt – three times at Halifax. He met Oliver Heywood whilst in jail [1685]. Whilst in jail, Midgley wrote ‘History of Halifax’ and ‘Halifax and its Gibbet Law placed in its True Light’. Midgley died in Halifax jail [18th July 1695]. His father died one month later. After Midgley’s death, the books were published after 1761 by William Bentley.

The Gibbet and the Maiden: a very British Punishment

In the days before modern policing, the authorities relied on the public’s fear of punishment as a means to keep law and order. No punishment was more feared than the instruments of execution known as The Gibbet and the Maiden. Here we take a look at these British ‘guillotines’ in use more than two centuries before the French Revolution!

Everyone has heard of ‘Madame Guillotine’. She was used during the French Revolution to execute the condemned as quickly and painlessly as possible. People of the time were moving away from more brutal techniques of the medieval period such as breaking on the wheel and the axe. These old methods were seen as barbaric and slow. Before the beheading machines, it was common for criminals to be beheaded with an axe or a sword. This method wasn’t always reliable. It depended on the blade being sharp, the strength of the executioner and his aim. There are many famous cases where executions did not go as planned. Here are some well-known ones.

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury was 65 years old when she was executed in 1541. She was one of the last surviving descendants of the Plantagenet dynasty, with a rival Catholic claim to the English throne. The usual executioner was away on the day she was to be beheaded, so a young and inexperienced executioner stood in. He did not do a good job; it was said that he hacked at her neck and shoulders and it took him ten blows to get the job done.

Mary, Queen of Scots was executed for treason in 1587. She was executed by a man named Bull. Poor Bull did not do the best job on this very important execution. His first swing missed her neck and hit the back of her head. The next swing was true but a little bit of sinew was left and had to be cut away. When he then picked up the severed head with what he thought was her hair, it turned out she was wearing a wig and her head fell to the floor. Additionally, her little lap dog was hiding in her skirts the whole time.

Jack Ketch was not a victim but an executioner during the reign of Charles II and James II. He was a well known botcher of executions. His execution of Lord Russell in 1683 went very badly, taking him many blows to get the job done. It was so bad that Ketch wrote a pamphlet apologising for it. Another well known mishap of his was on the illegitimate son of Charles II, James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, who was executed for his part in the Monmouth Rebellion to overthrow his uncle James II. James was said to have asked Ketch to deal only one blow, knowing that he had done such a bad job in the past. Ketch again didn’t manage it in one blow. After the first swing, James rose and looked reproachfully at Ketch then laid his head down again. It took five to seven blows to get it done.

So you can see why people would want a more efficient form of punishment, hence the guillotine. But the guillotine was not the first of its type. In Britain there were two well-known examples of early forms of guillotines.

The Maiden was made in Edinburgh in 1564 and over its 145 years of service it was used in 150 executions. It was gifted to Edinburgh by the Lord Provost and the magistrates of the city. It was a flat pack design so was not a constant fixture on the streets of Edinburgh. It was brought out when needed and then packed away. The lead weighted blade would be lifted by the rope which was then attached to a trigger. Once the trigger was released the blade would fall quickly due to the weight. People from all over Scotland were brought to Edinburgh to be beheaded by The Maiden. The crimes of the executed included murder, incest, stealing, treason, adultery, forgery and robbery.

An interesting and possibly ironic fact is that one of the well-known victims, James Douglas 4th Earl of Morton, may have been the person that came up with the idea of using a machine. He was executed for his part in the murder of Lord Darnley, husband of Mary, Queen of Scots. He was not arrested until 13 years after the murder.

Another well-known victim was Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll. He was not the only member of his family to be executed on The Maiden. His father was executed 24 years earlier for complicity in the death of King Charles I. Archibald was executed for his part in a plot to overthrow James I (James VI in Scotland). His plot was organised in parallel with the Monmouth rebellion. If you compare Archibald’s execution with Monmouth’s, it shows how two executions that happened within a month of each other could go very differently. Archibald died quickly and effectively with minimum suffering, whereas James would have been in pain and suffered.

At the end of the life of The Maiden it was stored away, but eventually found and is now on display at the National Museum of Scotland.

A replica of the Halifax Gibbet on its original site, 2008, with St Mary’s Catholic church, Gibbet Street, in the background

Another guillotine-style machine used in Britain was the Halifax gibbet. Some believe that the gibbet was the precursor to the Scottish Maiden. Though the exact date of the creation is unknown, it is believed to have been erected in the 16th century. It might seem strange that Halifax had a specialist beheading machine while other larger cities like London and York did not. But in the 16th century Halifax was an important centre of the English wool trade. The people of Halifax made woollen cloth which was a major source of income for the market town and for England. For this reason, it was important to protect the wool trade in the city.

Halifax was also a part of the manor of Wakefield. The lord of the manor of Wakefield had certain long-held privileges that gave him the right to have thieves that stole 13 1/2d and over executed. Around 100 people were executed by this law and 53 of them were executed by the gibbet. The Halifax gibbet looked very similar to the French guillotine apart from the blade which was axe-shaped instead of triangular. It was also never sharpened which meant it relied on the weight and drop to sever the head by tearing.

The gibbet was so well known that it was mentioned in a famous proverb called the thieves’ litany: “From Hull, from Halifax, from hell, ’tis thus, From all these three, good Lord delivers us”. However there was a way to escape the gibbet. If you got your head out before the axe fell and managed to run the mile to cross the parish boundary, you were free to go. You wouldn’t be brought back to continue the execution but you were banished, and if you crossed back over the boundary at any time you would be executed. Two men are known to have managed it. One never came back but the other did after seven years, thinking that because he’d escaped he was pardoned. He was not! He was executed as soon as he returned. A local legend about the gibbet says that during one execution a woman was riding by with a load of hampers. As she went by the gibbet, the execution happened and the head of the victim flew off the stand and either landed in a hamper or bit and held on to her apron.

The last execution was in 1650. Not long after Oliver Cromwell had the gibbet dismantled and the stand that it sat on was not found until 1839. There is a modern replica in the place of the original.

Though beheading by axe and sword did not always go to plan, it was still seen as the most reliable and painless way to execute a criminal, which is why it was mostly used on the noble classes. This is what makes the Halifax gibbet and The Maiden so unique in the UK as they were used to punish the common classes. The last beheading in the UK was in 1747 when it was replaced by hanging as the country’s main execution method. This remained the case right up to the last execution in the UK in 1964.

Print of the Halifax Gibbet in use, from Thomas Allen’s A New and Complete History of the County of York (1829)

History – The earliest known record of punishment by decapitation in Halifax is the beheading of John of Dalton in 1286,but official records were not maintained until the parish registers began in 1538. Between then and 1650, when the last executions took place, 56 men and women are recorded as having been decapitated. The total number of executions identified since 1286 is just short of 100.

Local weavers specialised in the production of kersey, a hardwearing and inexpensive woollen fabric that was often used for military uniforms; by the 16th century Halifax and the surrounding Calder Valley was the largest producer of the material in England. In the final part of the manufacturing process the cloth was hung outdoors on large structures known as tenterframes and left to dry, after having been conditioned by a fulling mill. Daniel Defoe wrote a detailed account of what he had been told of the gibbet’s history during his visit to Halifax in Volume 3 of his A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain, published in 1727. He reports that “Modern accounts pretend to say, it [the gibbet] was for all sorts of felons; but I am well assured, it was first erected purely, or at least principally, for such thieves as were apprehended stealing cloth from the tenters; and it seems very reasonable to think it was so”. Eighteenth-century historians argued that the area’s prosperity attracted the “wicked and ungovernable”; the cloth, left outside and unattended, presented easy pickings, and hence justified severe punishment to protect the local economy. James Holt on the other hand, writing in 1997, sees the Halifax Gibbet Law as a practical application of the Anglo-Saxon law of infangtheof. Royal assizes were held only twice a year in the area; to bring a prosecution was “vastly expensive”, and the stolen goods were forfeited to the Crown, as they were considered to be the property of the accused. But the Halifax Gibbet Law allowed “the party injured, to have his goods restored to him again, with as little loss and damage, as can be contrived; to the great encouragement of the honest and industrious, and as great terror to the wicked and evil doers.” The Halifax Gibbet’s final victims were Abraham Wilkinson and Anthony Mitchell. Wilkinson had been found guilty of stealing 16 yards (15 m) of russet-coloured kersey cloth, 9 yards (8.2 m) of which, found in his possession, was valued at “9 shillings at the least”, and Mitchell of stealing and selling two horses, one valued at 9 shillings and the other at 48 shillings. The pair were found guilty and executed on the same day, 30 April 1650. Writing in 1834 John William Parker, publisher of The Saturday Magazine, suggested that the gibbet might have remained in use for longer in Halifax had the bailiff not been warned that if he used it again he would be “called to public account for it”. Midgley comments that the final executions “were by some persons in that age, judged to be too severe; thence came it to pass, that the gibbet, and the customary law, for the forest of Hardwick, got its suspension”. Oliver Cromwell finally ended the exercise of Halifax Gibbet Law. To the Puritans it was “part of ancient ritual to be jettisoned along with all the old feasts and celebrations of the medieval world and the Church of Rome”. Moreover, it ran counter to the Puritan objection to imposing the death penalty for petty theft; felons were subsequently sent to the Assizes in York for trial. Noteable, Thomas Osborne, 1st Duke of Leeds, narrowly missed execution on the gibbet.

Thomas Osborne, 1st Duke of Leeds, KG (20 February 1632 – 26 July 1712) was an English Tory politician and peer. During the reign of Charles II of England, he was the leading figure in the English government for roughly five years in the mid-1670s. Osborne fell out of favour due to corruption and other scandals. He was impeached and eventually imprisoned in the Tower of London for five years until James II of England was accessed in 1685. In 1688, he was one of the Immortal Seven who invited William of Orange to depose James II during the Glorious Revolution. Osborne was again the leading figure in England’s government for a few years in the early 1690s before dying in 1712.

It is uncertain when the Halifax Gibbet was first introduced, but it may not have been until some time in the 16th century; before then decapitation would have been carried out by an executioner using an axe or a sword. The device, which seems to have been unique in England, consisted of two 15-foot (4.6 m) tall parallel beams of wood joined at the top by a transverse beam. Running in grooves within the beams was a square wooden block 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 m) in length, into the bottom of which was fitted an axe head weighing 7 pounds 12 ounces (3.5 kg). The whole structure sat on a platform of stone blocks, 9 feet (2.7 m) square and 4 feet (1.2 m) high, which was ascended by a flight of steps. A rope attached to the top of the wooden block holding the axe ran over a pulley at the top of the structure, allowing the block to be raised. The rope was then fastened by a pin to the structure’s stone base.The gibbet could be operated by cutting the rope supporting the blade or by pulling out the pin that held the rope. If the offender was to be executed for stealing an animal, a cord was fastened to the pin and tied to either the stolen animal or one of the same species, which was then driven off, withdrawing the pin and allowing the blade to drop. In an early contemporary account of 1586 Raphael Holinshed attests to the efficiency of the gibbet, and adds some detail about the participation of the onlookers:

‘In the nether end of the sliding block is an axe keyed or fastened with an iron into the wood, which being drawn up to the top of the frame is there fastened by a wooden pin … unto the middest of which pin also there is a long rope fastened that cometh down among the people, so that when the offender hath made his confession, and hath laid his neck over the nethermost block, every man there present doth either take hold of the rope (or putteth forth his arm so near to the same as he can get, in token that he is willing to see true justice executed) and pulling out the pin in this manner, the head block wherein the axe is fastened doth fall down with such violence, that if the neck of the transgressor were so big as that of a bull, it should be cut in sunder at a stroke, and roll from the body by a huge distance.’

An article in the September 1832 edition of The Imperial Magazine describes the victim’s final moments:

‘The persons who had found the verdict, and the attending clergymen, placed themselves on the scaffold with the prisoner. The fourth psalm was then played round the scaffold on the bagpipes, after which the minister prayed with the prisoner till he received the final stroke.’

In Thomas Deloney’s novel Thomas of Reading (1600) the invention of the Halifax Gibbet is attributed to a friar, who proposed the device as a solution to the difficulty of finding local residents willing to act as hangmen.

Although the guillotine as a method of beheading is most closely associated in the popular imagination with late 18th-century Revolutionary France, several other decapitation devices had long been in use throughout Europe. It is uncertain whether Dr Guillotin was familiar with the Halifax Gibbet. A 16th century device constructed in Edinburgh is called the Maiden. It dates from 1564, and those it executed included James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton in 1584. The story, published sixty years later, was that he had been responsible for its introduction after seeing the Halifax Gibbet, but this story is unsupported. The Maiden was stored and is now on display in the National Museum of Scotland. It is rather shorter than the Halifax Gibbet, standing only 10 feet (3.0 m) tall, the same height as the French guillotine.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend