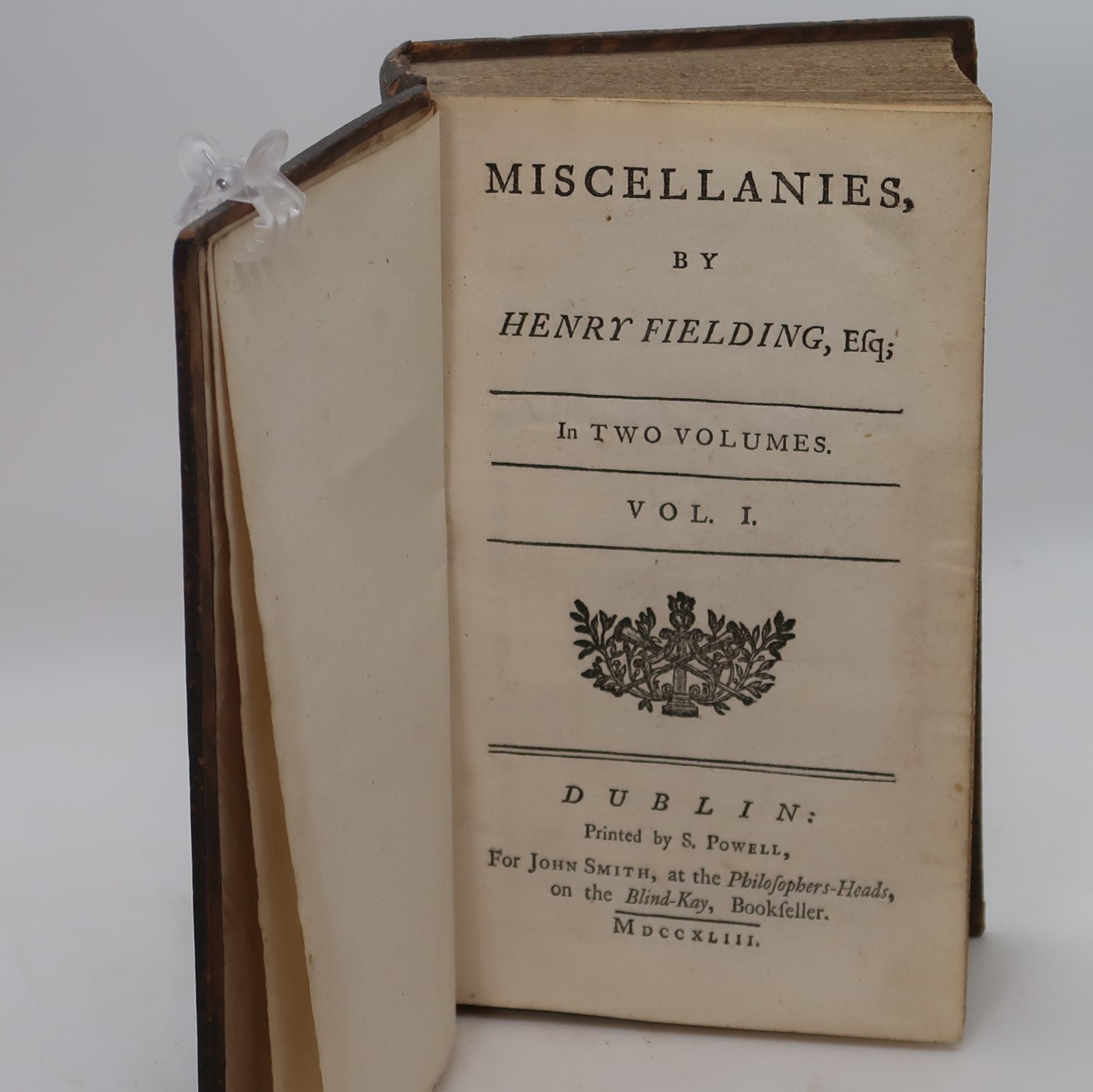

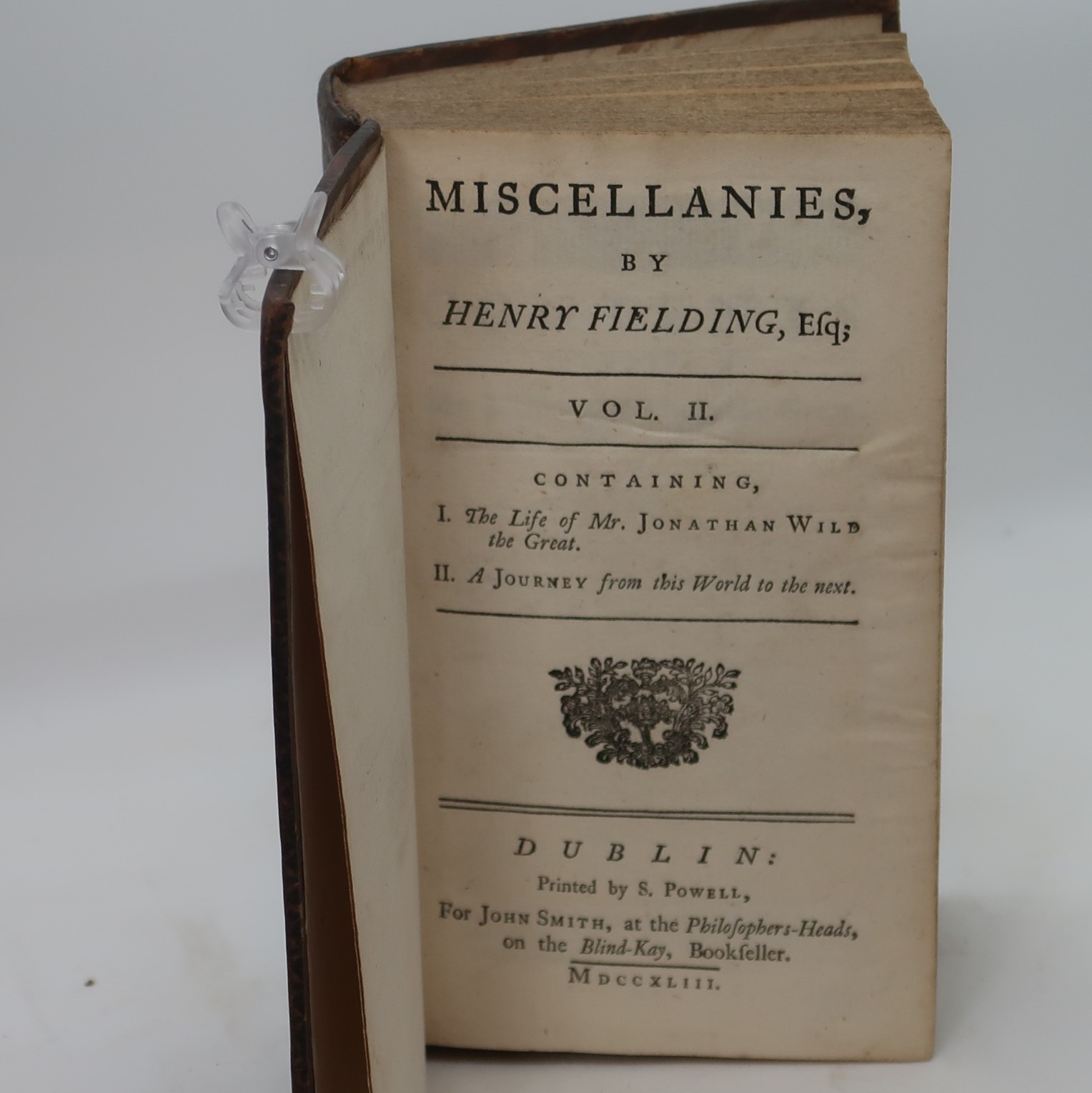

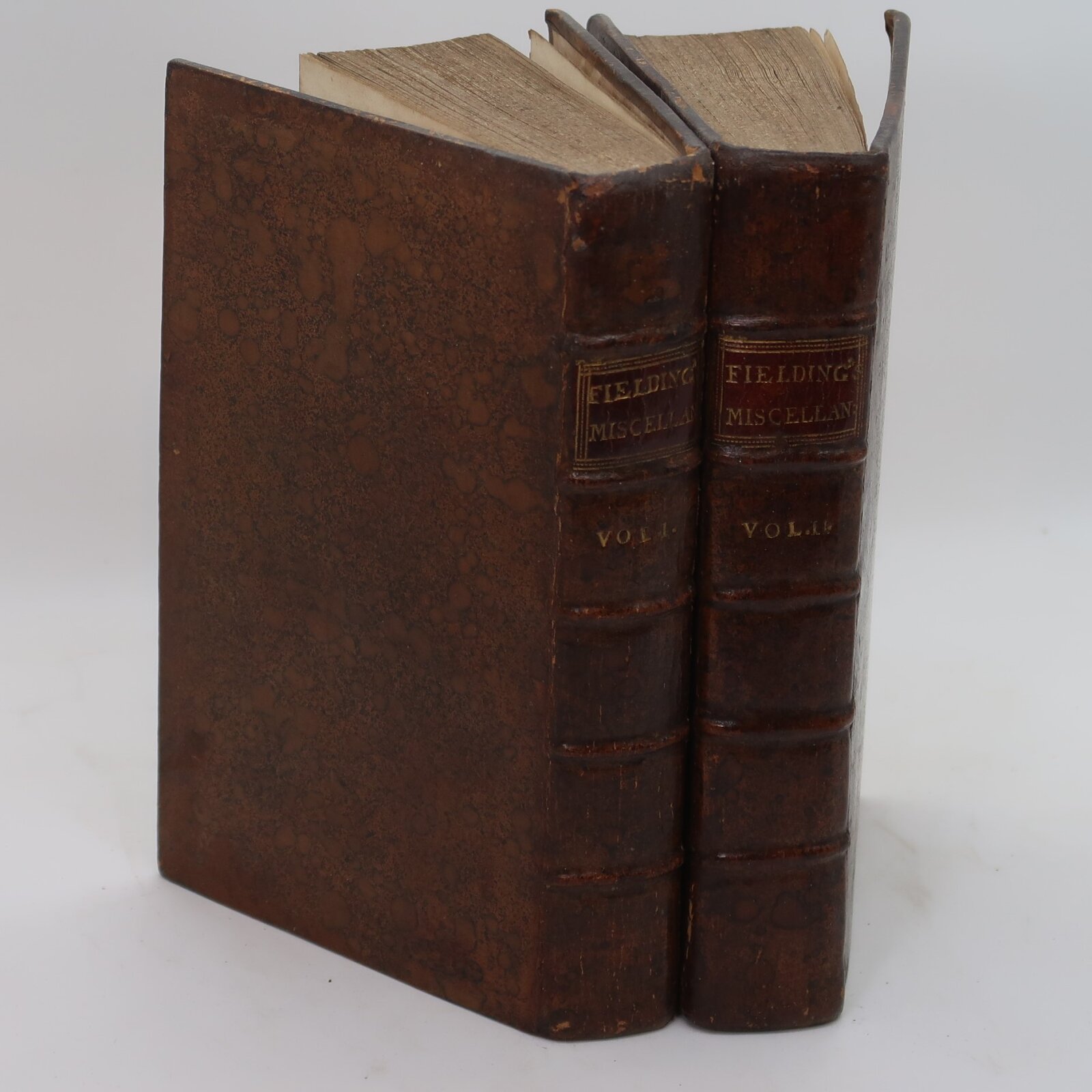

Fielding's Miscellany. Volumes I. & II.

By Henry Fielding.

Printed: 1743

Publisher: John Smith. Dublin

Edition: First and only Dublin edition

| Dimensions | 11 × 18 × 3.5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 11 x 18 x 3.5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Item information

Description

Brown speckled calf binding with red title plate and gilt lettering on the spine.

The first and only Dublin edition.

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist and dramatist known for his earthy humour and satire. His comic novel Tom Jones is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders of the traditional English novel. He also holds a place in the history of law enforcement, having used his authority as a magistrate to found the Bow Street Runners, London’s first intermittently funded, full-time police force.

The Theatrical Licensing Act of 1737 is said to be a direct response to his activities in writing for the theatre. Although the play that triggered the act was the unproduced, anonymously authored The Golden Rump, Fielding’s dramatic satires had set the tone. Once it was passed, political satire on stage became all but impossible. Fielding retired from the theatre and resumed his legal career to support his wife Charlotte Craddock and two children by becoming a barrister, joining the Middle Temple in 1737 and being called to the bar there in 1740.

Fielding’s lack of financial acumen meant the family often endured periods of poverty, but were helped by Ralph Allen, a wealthy benefactor, on whom Squire Allworthy in Tom Jones would be based. Allen went on to provide for the education and support of Fielding’s children after the writer’s death.

Fielding never stopped writing political satire and satires of current arts and letters. The Tragedy of Tragedies (for which Hogarth designed the frontispiece) was, for example, quite successful as a printed play. Based on his earlier Tom Thumb, this was another of Fielding’s irregular plays published under the name of H. Scriblerus Secundus, a pseudonym intended to link himself ideally with the Scriblerus Club of literary satirists founded by Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope and John Gay.He also contributed several works to journals.

From 1734 to 1739, Fielding wrote anonymously for the leading Tory periodical, The Craftsman, against the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole.His patron was the opposition Whig MP George Lyttelton, a boyhood friend from Eton to whom he later dedicated Tom Jones. Lyttelton followed his leader Lord Cobham in forming a Whig opposition to Walpole’s government called the Cobhamites, which included another of Fielding’s Eton friends, William Pitt. In The Craftsman, Fielding voiced an opposition attack on bribery and corruption in British politics. Despite writing for the opposition to Walpole, which included Tories as well as Whigs, Fielding was “unshakably a Whig” and often praised Whig heroes such as the Duke of Marlborough and Gilbert Burnet.

Fielding dedicated his play Don Quixote in England to the opposition Whig leader Lord Chesterfield. It appeared on 17 April 1734, the same day writs were issued for the general election. He dedicated his 1735 play The Universal Gallant to Charles Spencer, 3rd Duke of Marlborough, a political follower of Chesterfield. The other prominent opposition paper, Common Sense, founded by Chesterfield and Lyttelton, was named after a character in Fielding’s Pasquin (1736). Fielding wrote at least two articles for it in 1737 and 1738.

Fielding continued to air political views in satirical articles and newspapers in the late 1730s and early 1740s. He was the main writer and editor from 1739 to 1740 for the satirical paper The Champion, which was sharply critical of Walpole’s government and of pro-government literary and political writers. He sought to evade libel charges by making its political attacks so funny or embarrassing to the victim that a publicized court case would seem even worse. He later became chief writer for the Whig government of Henry Pelham.

Fielding took to novel writing in 1741, angered by Samuel Richardson’s success with Pamela. His first success was an anonymous parody of that novel, called Shamela. This follows the model of Tory satirists of the previous generation, notably Swift and Gay.

Fielding followed this with Joseph Andrews (1742), an original work supposedly dealing with Pamela’s brother, Joseph. His purpose, however, was more than parody, for as stated in the preface, he intended a “kind of writing which I do not remember to have seen hitherto attempted in our language.” In what Fielding called a “comic epic poem in prouse”, he blended two classical traditions: that of the epic, which had been poetic, and that of the drama, but emphasizing the comic rather than the tragic. Another distinction of Joseph Andrews and the novels to come was use of everyday reality of character and action, as opposed to the fables of the past. While begun as a parody, it developed into an accomplished novel in its own right and is seen as Fielding’s debut as a serious novelist. In 1743, he published a novel in the Miscellanies volume III (which was the first volume of the Miscellanies): The Life and Death of Jonathan Wild, the Great, which is sometimes counted as his first, as he almost certainly began it before he wrote Shamela and Joseph Andrews. It is a satire of Walpole equating him and Jonathan Wild, the gang leader and highwayman. He implicitly compares the Whig party in Parliament with a gang of thieves run by Walpole, whose constant desire to be a “Great Man” (a common epithet with Walpole) ought to culminate in the antithesis of greatness: hanging.

His anonymous The Female Husband (1746) fictionalizes a case in which a female transvestite was tried for duping another woman into marriage; this was one of several small pamphlets costing sixpence. Though a minor piece in Fielding’s curve, it reflects his preoccupation with fraud, shamming and masks.

His greatest work is The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749), a meticulous comic novel with elements of the picaresque and the Bildungsroman, telling a convoluted, hilarious tale of how a foundling came into a fortune. The plot is too ingenious for a simple summary; it tells of Tom’s alienation from his foster father, Squire Allworthy, and his sweetheart, Sophia Western, and his reconciliation with them after lively and dangerous adventures on the road and in London. It triumphs as a presentation of English life and character in the mid-18th century. Every social type is represented and through them every shade of moral behaviour. Fielding’s varied style tempers the basic seriousness of the novel and his authorial comment before each chapter adds a dimension to a conventional, straightforward narrative.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend