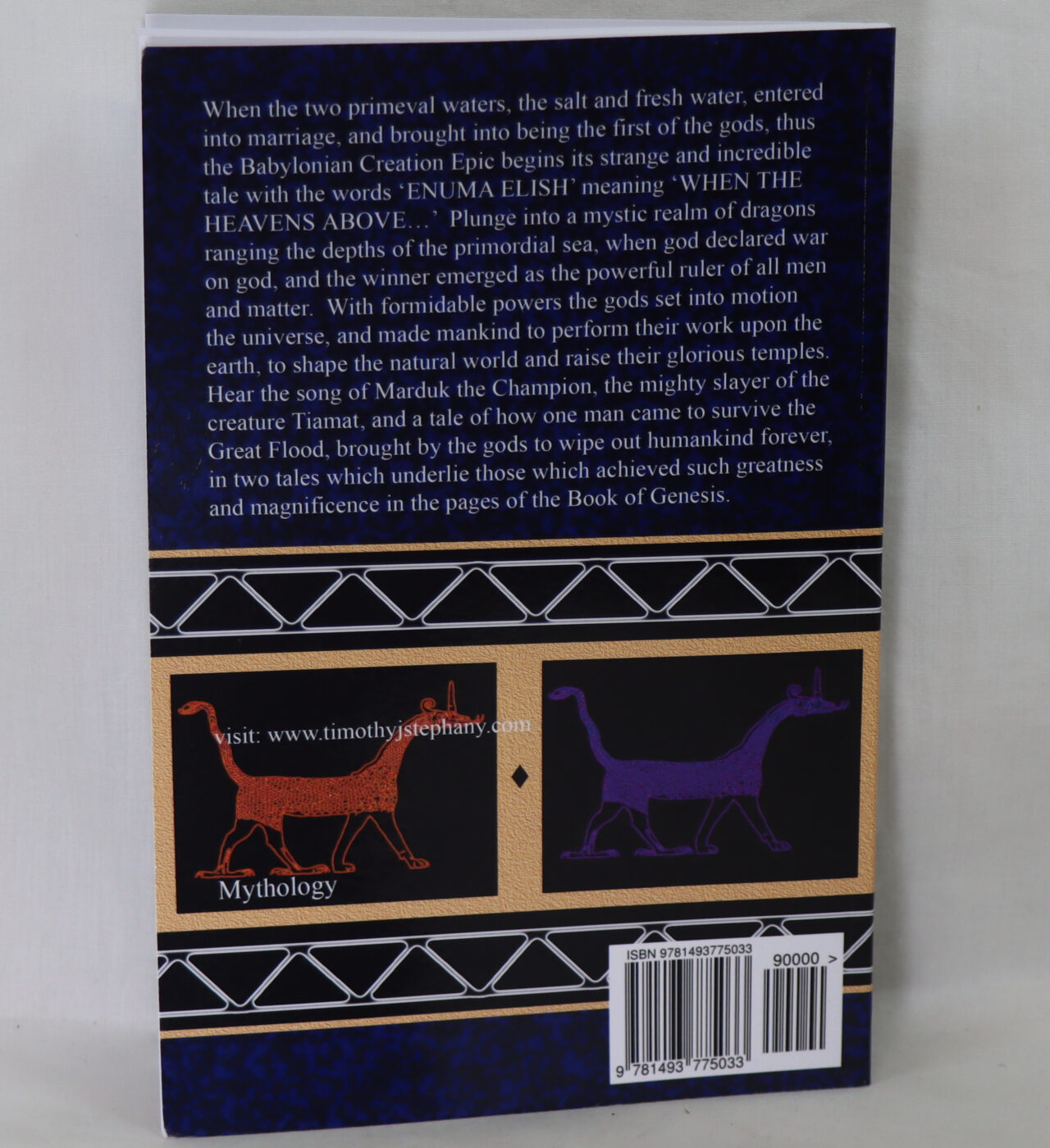

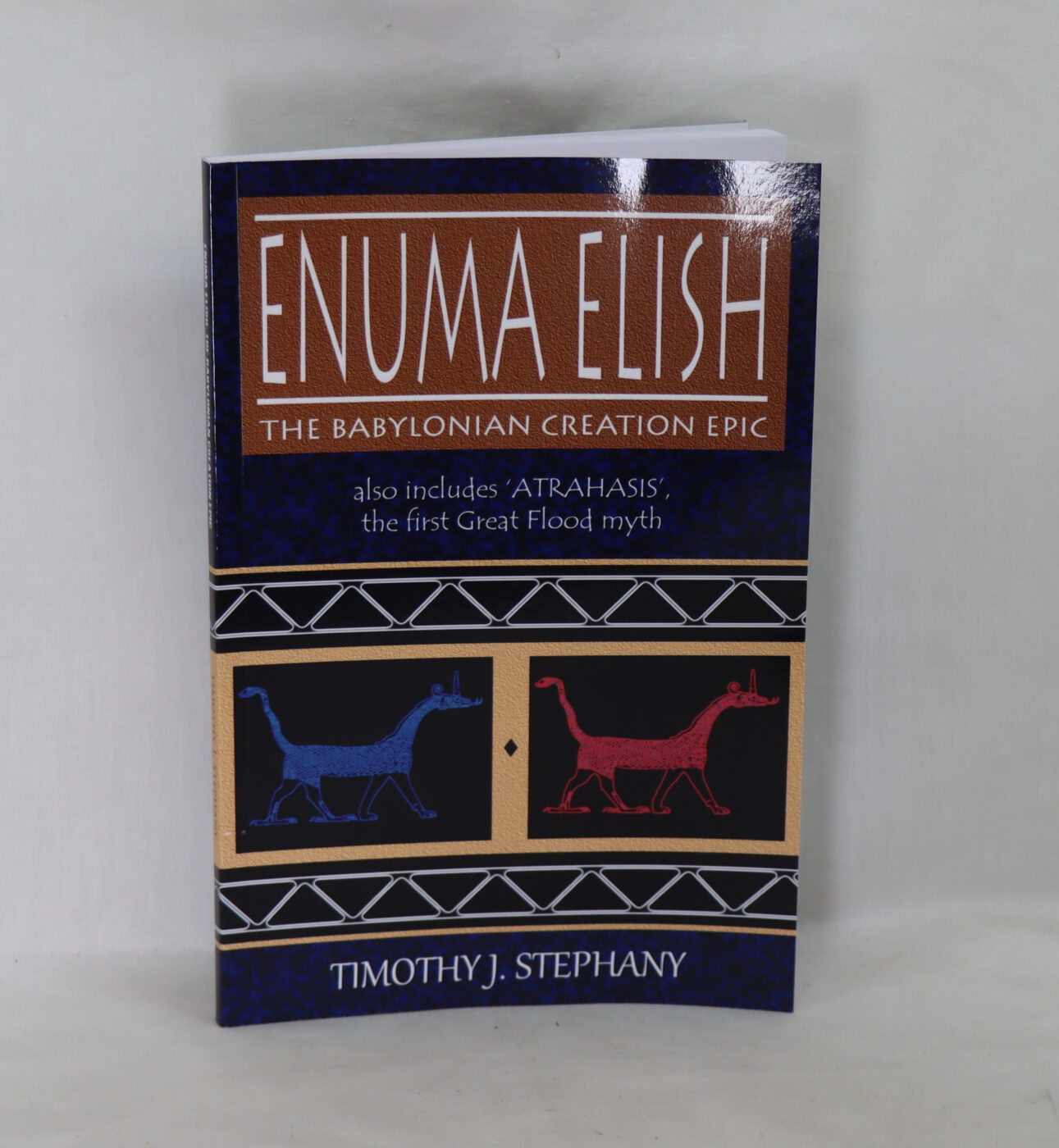

Enuma Elish. The Babylonian Creation Epic.

By Timothy J Stephany

ISBN: 9781493775033

Printed: 2014

Publisher: Timothy J Stephany.

| Dimensions | 15 × 23 × 1 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 15 x 23 x 1

Condition: As new (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Paperback. Black cover with white title drawn images.

- We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- This new book has a £3 discount when collected from our shop

For conditions, please view our photographs. When the two primeval waters, the salt and fresh water, entered into marriage, and brought into being the first of the gods, thus the Babylonian Creation Epic begins its strange and incredible tale with the words ‘ENUMA ELISH’ meaning ‘WHEN THE HEAVENS ABOVE…’ Plunge into a mystic realm of dragons ranging the depths of the primordial sea, when god declared war on god, and the winner emerged as the powerful ruler of all men and matter. With formidable powers the gods set into motion the universe, and made mankind to perform their work upon the earth, to shape the natural world and raise their glorious temples. Hear the song of Marduk the Champion, the mighty slayer of the creature Tiamat, and a tale of how one man came to survive the Great Flood, brought by the gods to wipe out humankind forever, in two tales which underlie those which achieved such greatness and magnificence in the pages of the Book of Genesis.

Review: Viewed in a modern hindsight, creation myths have been attempts to explain the inexplicable, yet for the people of their time, they were explanations, in much the same way that we now look to scientists for explanations; the Enuma Elish is one such ‘explanation’. Jung pointed to their psychological significance, while Cambell demonstrated a remarkable uniformity in the elements from which these myths were composed, almost independent of the cultures in which they were found, suggesting that something was known that we now do not know, and our only record are the myths themselves, and it is the power that these myths still seem to have when heard, that contributes to their mystery. Sarna’s brilliant book ‘Understanding Genesis’, makes it very clear that the early Hebrew writers were well aware of contemporary cultural traditions, but as they were ‘pagan’ there was an attempt to distance Hebraic accounts from similar ones, and in the case of the Psalms, to distinguish Hebraic perspectives from contemporary analogues.

The introduction to this translation makes it very clear that the old myths did not go away or disappear. If Isaiah can allude to characters in those myths, then it is clear that such allusions would not have taken place if the people had not understood what the allusion referred to. Factual information about the tablets on which the myth was written are kept to the minimum. Stephany avoids a Cambell – type of approach, although he does once refer to Norse Mythology and Hindu Mythology. To include all possible sources or analogues – he does not mention Hesiod or the ancient Egyptians, would have resulted in a massive introduction, which would have detracted from the simple beauty in this translation.

Want to know more about this item?

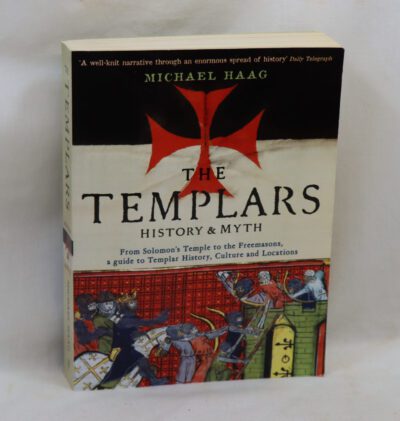

Related products

Share this Page with a friend