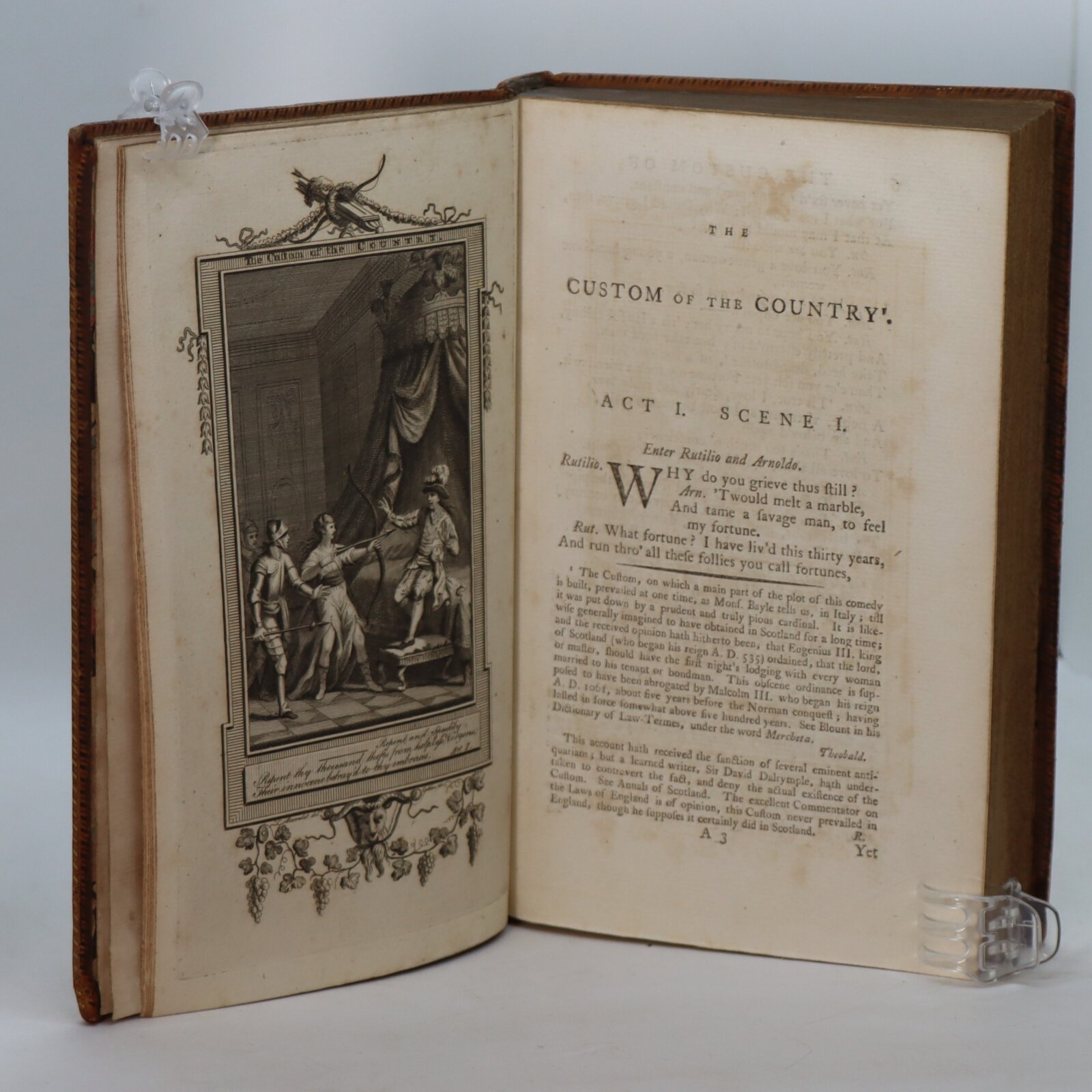

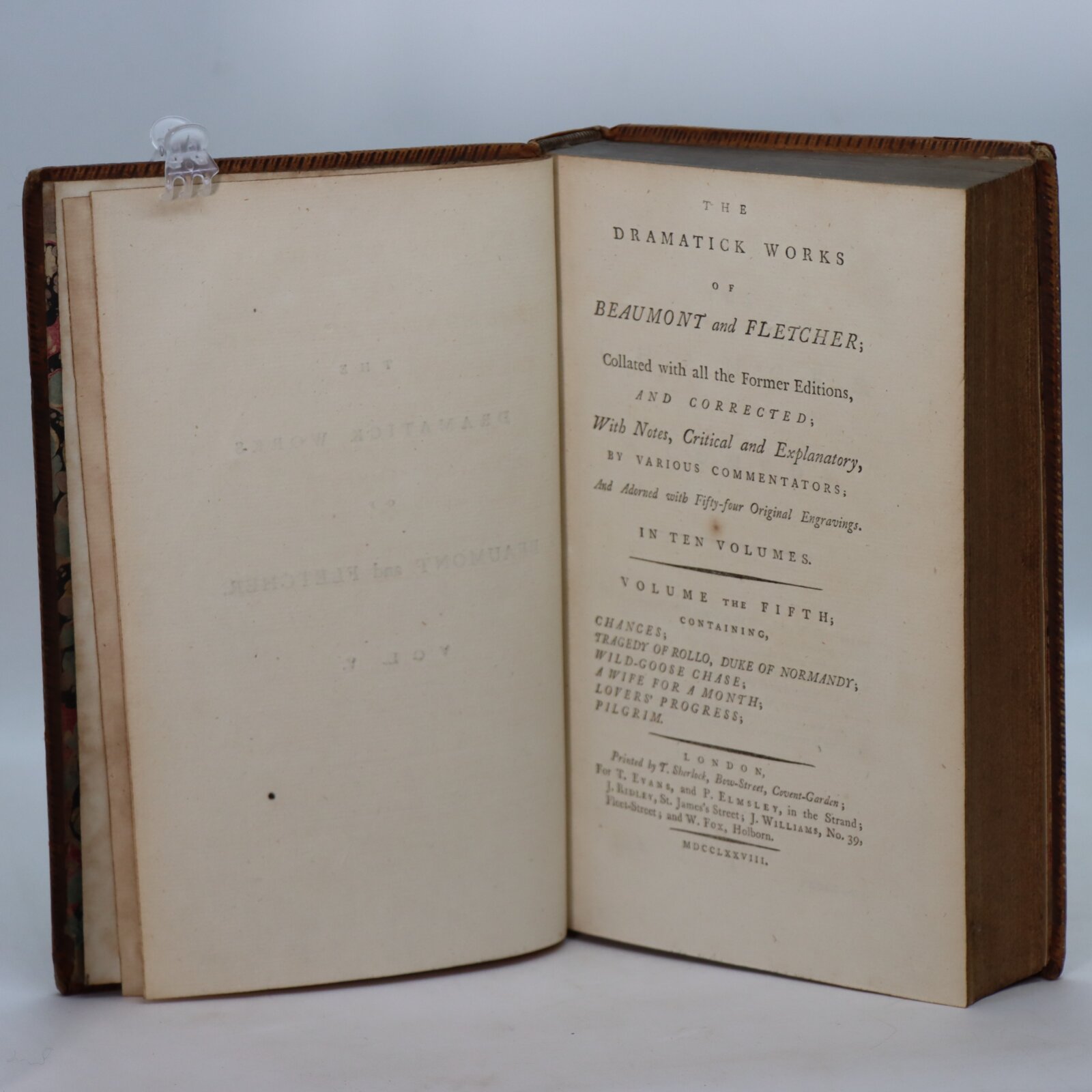

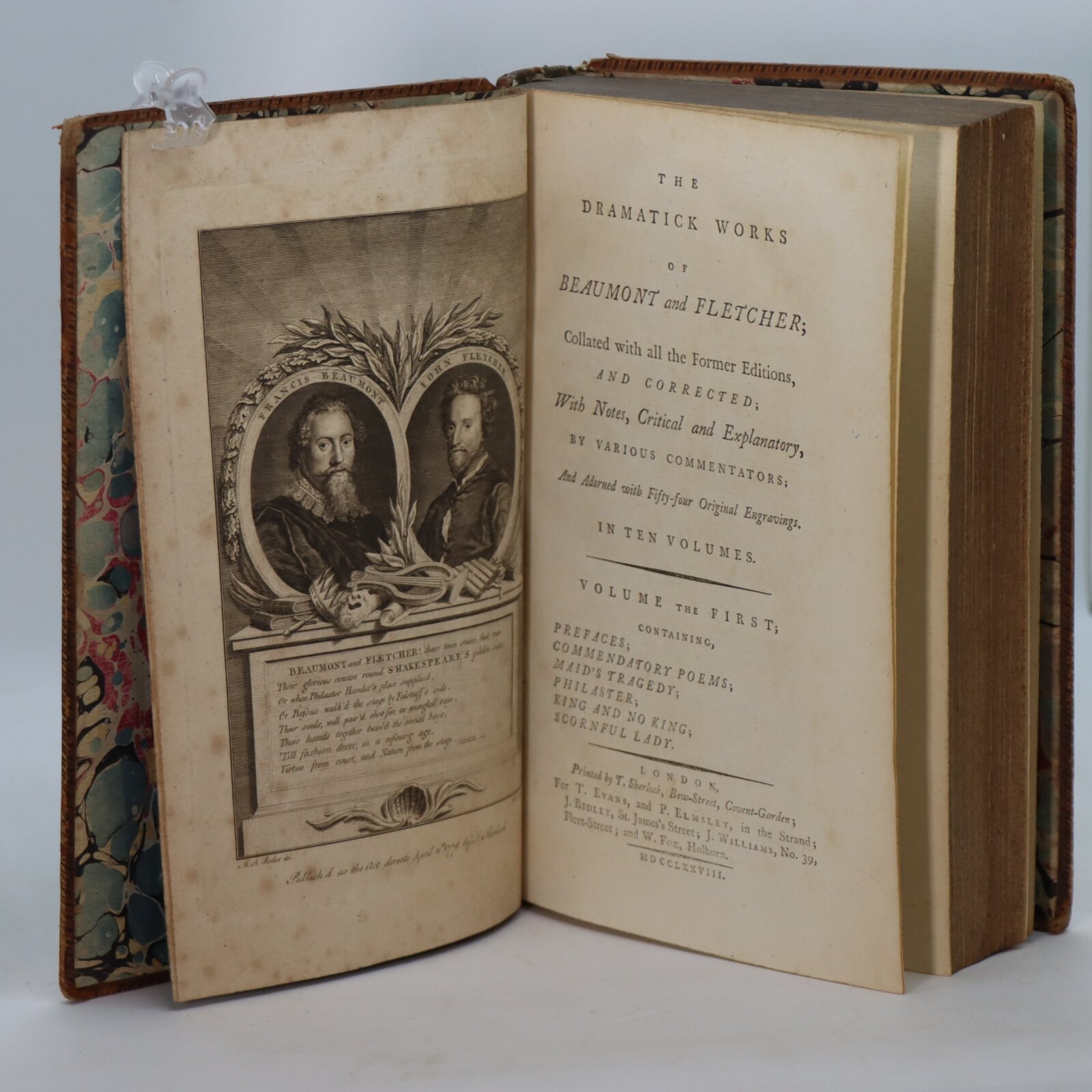

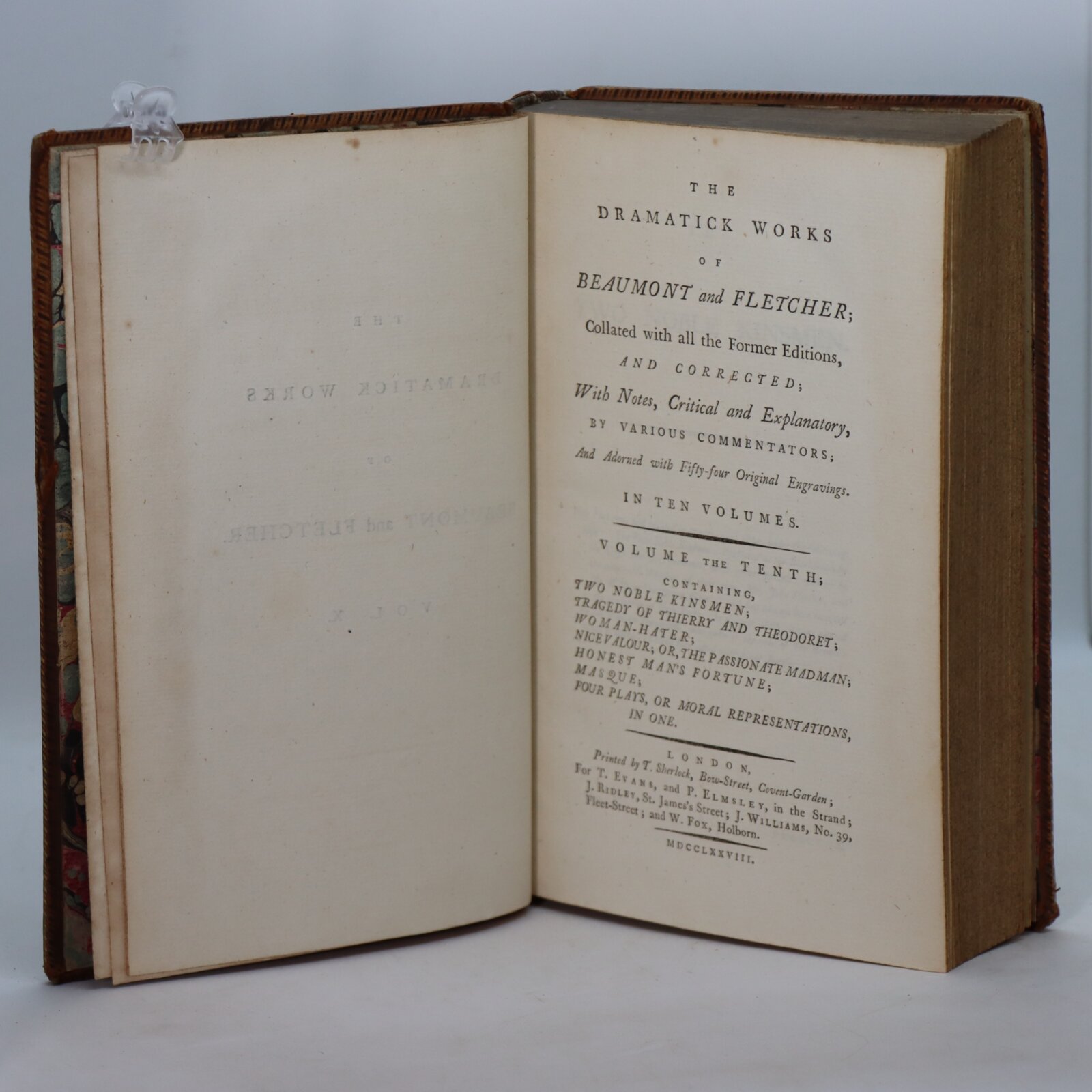

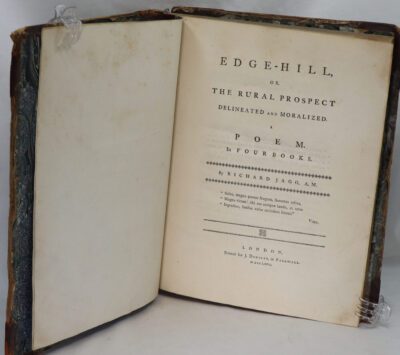

Beaumont & Fletcher's Works. In Ten Volumes.

By Francis Beaumont & John Fletcher

Printed: 1778

Publisher: & P Elmsley. London

| Dimensions | 14 × 22 × 4 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 14 x 22 x 4

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Your items

Item information

Description

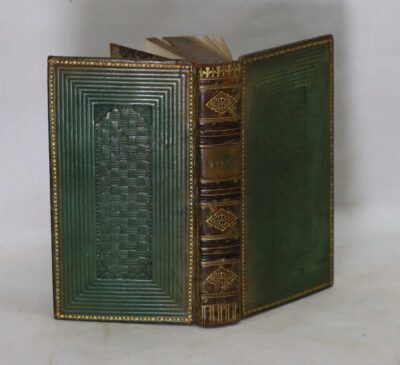

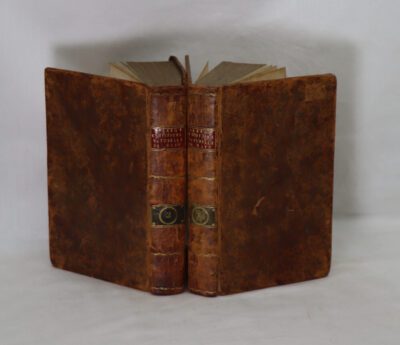

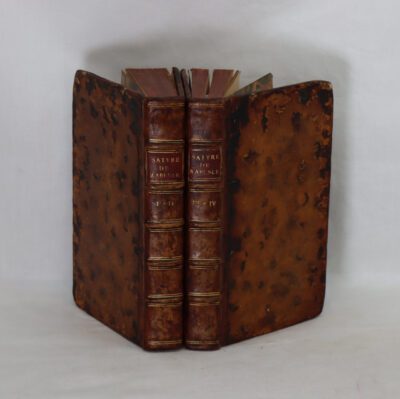

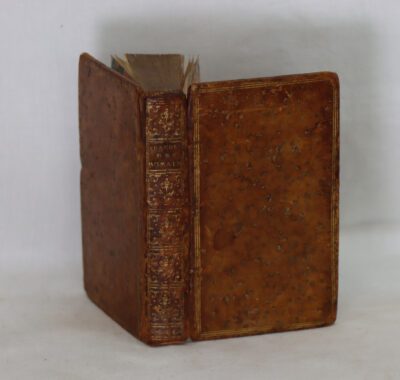

Tan leather full binding. Gilt entwined edging to both boards. Red and green title plates with Gilt lettering, banding, ornate decoration and volume number on the spine. Dimensions are for one volume.

It is the intent of F.B.A. to provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this book offered so to almost stimulate your feel and touch on the book. If requested, more traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Beaumont and Fletcher were the English dramatists Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, who collaborated in their writing during the reign of James I (1603–25).

They became known as a team early in their association, so much so that their joined names were applied to the total canon of Fletcher, including his solo works and the plays he composed with various other collaborators including Philip Massinger and Nathan Field.

The first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647 contained 35 plays; 53 plays were included in the second folio in 1679. Other works bring the total plays in the canon to about 55. While scholars and critics will probably never render a unanimous verdict on the authorship of all these plays—especially given the difficulties of some of the individual cases—contemporary scholarship has arrived at a corpus of about 12 to 15 plays that are the work of both men.

The Beaumont and Fletcher folios are two large folio collections of the stage plays of John Fletcher and his collaborators. The first was issued in 1647, and the second in 1679. The two collections were important in preserving many works of English Renaissance drama.

The 1647 folio was published by the booksellers Humphrey Moseley and Humphrey Robinson. It was modelled on the precedents of the first two folio collections of Shakespeare’s plays, published in 1623 and 1632, and the first two folios of the works of Ben Jonson of 1616 and 1640–1. The title of the book was given as Comedies and Tragedies Written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher Gentlemen, though the prefatory matter in the folio recognised that Philip Massinger, rather than Francis Beaumont, collaborated with Fletcher on some of the plays included in the volume. (In fact, the 1647 volume “contained almost nothing of Beaumont’s” work.) Seventeen works in Fletcher’s canon that had already been published prior to 1647, and the rights to these plays belonged to the stationers who had issued those volumes; Robinson and Moseley therefore concentrated on the previously unpublished plays in the Fletcher canon.

Most of these plays had been acted onstage by the King’s Men, the troupe of actors for whom Fletcher had functioned as house dramatist for most of his career. The folio featured a dedication to Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke, signed by ten of the King’s Men – John Lowin, Joseph Taylor, Richard Robinson, Robert Benfield, Eliard Swanston, Thomas Pollard, Hugh Clark, William Allen, Stephen Hammerton, and Theophilus Bird – all idled by the closing of the theatres in 1642. It also contained two addresses to the reader, by James Shirley and by Moseley, and 37 commendatory poems, long and short, by figures famous and obscure, including Shirley, Ben Jonson, Richard Lovelace, Robert Herrick, Richard Brome, Jasper Mayne, Thomas Stanley, and Sir Aston Cockayne.

The 1647 folio contains 35 works – 34 plays and 1 masque.

The 1647 folio has attracted significant attention from scholars and bibliographers, and various specialised studies of the folio (books on the book) have been written. As with Shakespeare’s First Folio, the typesetting of individual compositors and the work of individual printers has been traced and analysed – including that of Susan Islip, one of the rare instances of a female printer in the 17th century.

The second folio, titled Fifty Comedies and Tragedies, was published by the booksellers Henry Herringman, John Martyn, and Richard Marriot; the printing was done by J. Macock. The three stationers had obtained the rights to previously published works and added 18 dramas to the 35 of the first folio, for a total of 53. The second folio added features that the first lacked. Many songs in the plays were given in full. Cast lists were prefixed to 25 of the dramas, lists that provide the names of the leading actors in the original productions of the plays. These lists can be informative on the companies involved and the dates of first productions; the cast list prefixed to The Honest Man’s Fortune, for example, reveals that the play was originally staged by the Lady Elizabeth’s Men in the 1612–13 period.

On the negative side, the texts in the second folio were set into type from the previously printed quarto texts, and never from manuscript; the texts of the plays in the first collection were printed from manuscript sources.

The implicit canon, nearly realized by the contents of the second folio, comprises dramatic works written by Beaumont or Fletcher; either alone, together, or in collaboration with other playwrights. By this rule, likely, four plays should be excluded (The Laws of Candy by John Ford, Wit at Several Weapons by Middleton and Rowley, The Nice Valour by Middleton, and The Coronation by James Shirley), and three more extant plays should be included (Barnavelt, A Very Woman, and Henry VIII). A Very Woman was printed in a volume of Massinger’s plays in 1655, while Sir John van Olden Barnavelt remained in manuscript until the 19th century. Henry VIII was first published in the Shakespeare First Folio of 1623.

At least five plays, no longer extant, may also belong in the canon. Four of these were entered to Moseley in the Stationers’ Register between 1653 and 1660, possibly with the intent of printing them in the second folio: Cardenio (Shakespeare and Fletcher?), A Right Woman (Beaumont and Fletcher?), The Wandering Lovers (Fletcher?), and The Jeweler of Amsterdam (Fletcher, Field, and Massinger?). A fifth non-extant play, The Queen was questionably attributed to Fletcher by a contemporary.

The folios contain two works that are generally thought to be the work of Beaumont alone – The Knight of the Burning Pestle and The Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray’s Inn – and fifteen that are solo efforts by Fletcher, and perhaps a dozen that are actual Beaumont/Fletcher collaborations. The rest are Fletcher’s collaborations with Massinger and other writers.

Francis Beaumont (1584 – 6 March 1616) was a dramatist in the English Renaissance theatre, most famous for his collaborations with John Fletcher.

Beaumont was the son of Sir Francis Beaumont of Grace Dieu, near Thringstone in Leicestershire, a justice of the common pleas. His mother was Anne, the daughter of Sir George Pierrepont (d. 1564), of Holme Pierrepont, and his wife Winnifred Twaits. Beaumont was born at the family seat and was educated at Broadgates Hall (now Pembroke College, Oxford) at age thirteen. Following the death of his father in 1598, he left university without a degree and followed in his father’s footsteps by entering the Inner Temple in London in 1600.

Accounts suggest that Beaumont did not work long as a lawyer. He became a student of poet and playwright Ben Jonson; he was also acquainted with Michael Drayton and other poets and dramatists, and decided that was where his passion lay. His first work, Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, appeared in 1602. The 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica describes the work as “not on the whole discreditable to a lad of eighteen, fresh from the popular love-poems of Marlowe and Shakespeare, which it naturally exceeds in long-winded and fantastic diffusion of episodes and conceits.” In 1605, Beaumont wrote commendatory verses to Jonson’s Volpone.

Beaumont’s collaboration with Fletcher may have begun as early as 1605. They had both hit an obstacle early in their dramatic careers with notable failures; Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle, first performed by the Children of the Blackfriars in 1607, was rejected by an audience who, the publisher’s epistle to the 1613 quarto claims, failed to note “the privie mark of irony about it;” that is, they took Beaumont’s satire of old-fashioned drama as an old-fashioned drama. The play received a lukewarm reception. The following year, Fletcher’s Faithful Shepherdess failed on the same stage. In 1609, however, the two collaborated on Philaster, which was performed by the King’s Men at the Globe Theatre and at Blackfriars. The play was a popular success, not only launching the careers of the two playwrights but also sparking a new taste for tragicomedy. According to a mid-century anecdote related by John Aubrey, they lived in the same house on the Bankside in Southwark, “sharing everything in the closest intimacy.” About 1613 Beaumont married Ursula Isley, daughter and co-heiress of Henry Isley of Sundridge in Kent, by whom he had two daughters: Elizabeth and Frances (a posthumous child). He had a stroke between February and October 1613, after which he wrote no more plays, but was able to write an elegy for Lady Penelope Clifton, who died 26 October 1613. Beaumont died in 1616 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. Although today Beaumont is remembered as a dramatist, during his lifetime he was also celebrated as a poet.

It was once written of Beaumont and Fletcher that “in their joint plays their talents are so…completely merged into one, that the hand of Beaumont cannot clearly be distinguished from that of Fletcher.” Yet this romantic notion did not stand up to critical examination.

In the seventeenth century, Sir Aston Cockayne, a friend of Fletcher’s, specified that there were many plays in the 1647 Beaumont and Fletcher folio that contained nothing of Beaumont’s work, but rather featured the writing of Philip Massinger. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century critics like E.H.C. Oliphant subjected the plays to a self-consciously literary, and often subjective and impressionistic, reading – but nonetheless began to differentiate the hands of the collaborators. This study was carried much farther, and onto a more objective footing, by twentieth-century scholars, especially Cyrus Hoy. Short of absolute certainty, a critical consensus has evolved on many plays in the canon of Fletcher and his collaborators; in regard to Beaumont, the schema below is among the least controversial that has been drawn.

By Beaumont alone:

- The Knight of the Burning Pestle, comedy (performed 1607; printed 1613)

- The Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray’s Inn, masque (performed 20 February 1613; printed 1613?)

With Fletcher:

- The Woman Hater,comedy (1606; 1607)

- Cupid’s Revenge,tragedy (c. 1607–12; 1615)

- Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding,tragicomedy (c. 1609; 1620)

- The Maid’s Tragedy,tragedy (c. 1609; 1619)

- A King and No King,tragicomedy (1611; 1619)

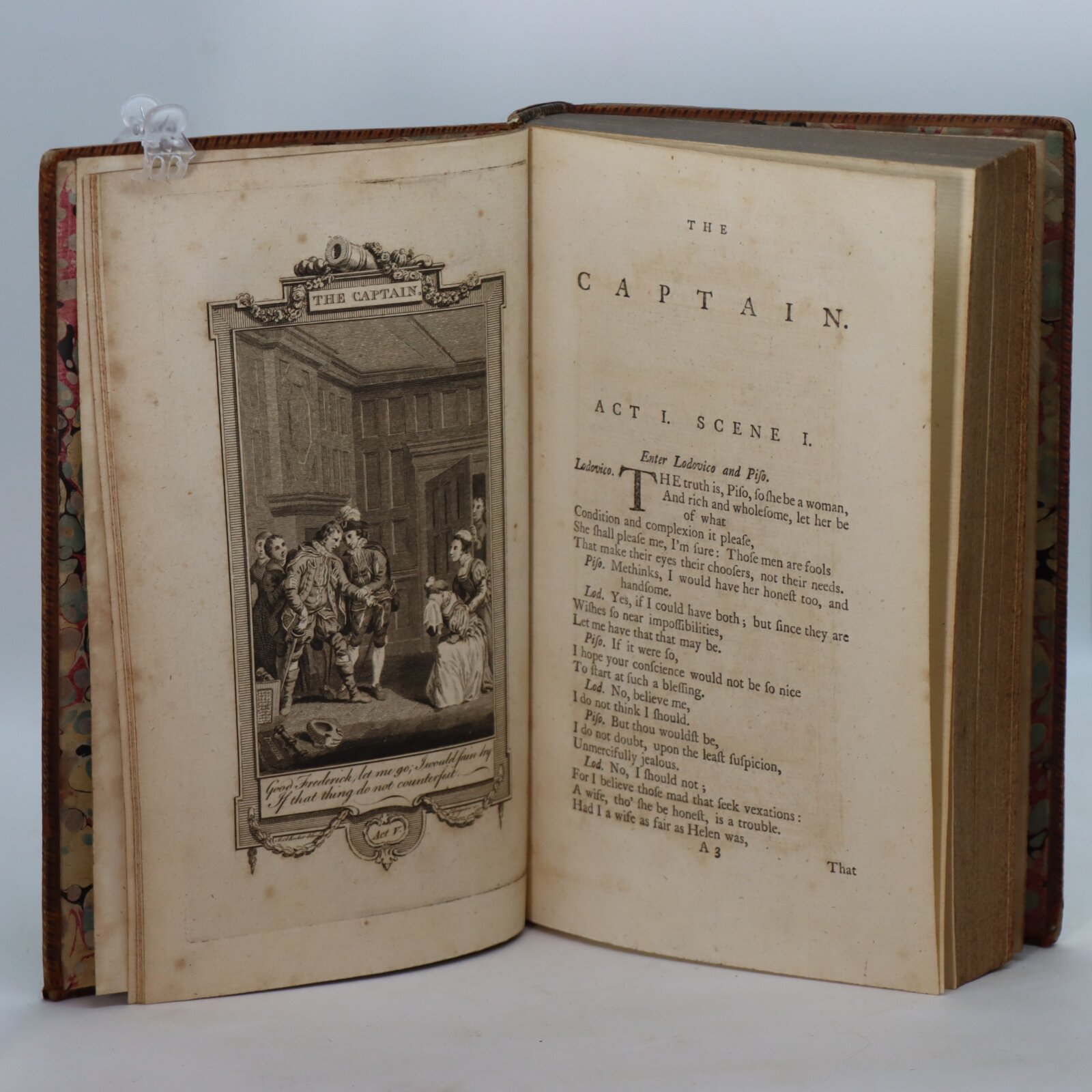

- The Captain,comedy (c. 1609–12; 1647)

- The Scornful Lady,comedy (c. 1613; 1616)

- Love’s Pilgrimage,tragicomedy (c. 1615–16; 1647)

- The Noble Gentleman,comedy (licensed 3 February 1626; 1647)

Beaumont/Fletcher plays, later revised by Massinger:

- Thierry and Theodoret,tragedy (c. 1607? 1621)

- The Coxcomb,comedy (c. 1608–10; 1647)

- Beggars’ Bush,comedy (c. 1612–13? revised 1622? 1647)

- Love’s Cure,comedy (c. 1612–13? revised 1625? 1647)

Because of Fletcher’s highly distinctive and personal pattern of linguistic preferences and contractional forms (ye for you, ‘em for them, etc.), his hand can be distinguished fairly easily from Beaumont’s in their collaborations. In A King and No King, for example, Beaumont wrote all of Acts I, II, and III, plus scenes IV. iv and V. ii & iv; Fletcher wrote only the first three scenes in Act IV (IV, i–iii) and the first and third scenes in Act V (V, i & iii) – so that the play is more Beaumont’s than Fletcher’s. The same is true of The Woman Hater, The Maid’s Tragedy, The Noble Gentleman, and Philaster. On the other hand, Cupid’s Revenge, The Coxcomb, The Scornful Lady, Beggar’s Bush, and The Captain are more Fletcher’s than Beaumont’s. In Love’s Cure and Thierry and Theodoret, the influence of Massinger’s revision complicates matters; but in those plays too, Fletcher appears to be the majority contributor, Beaumont the minority.

John Fletcher (1579–1625) was a Jacobean playwright. Following William Shakespeare as house playwright for the King’s Men, he was among the most prolific and influential dramatists of his day; during his lifetime and in the early Restoration, his fame rivalled Shakespeare’s. He collaborated on writing plays with Francis Beaumont, and with Shakespeare on two plays.

Though his reputation has declined since, Fletcher remains an important transitional figure between the Elizabethan popular tradition and the popular drama of the Restoration.

Fletcher was born in December 1579 (baptised 20 December) in Rye, Sussex, and died of the plague in August 1625 (buried 29 August in St. Saviour’s, Southwark). His father Richard Fletcher was an ambitious and successful cleric who was in turn Dean of Peterborough, Bishop of Bristol, Bishop of Worcester and Bishop of London (shortly before his death), as well as chaplain to Queen Elizabeth. As Dean of Peterborough, Richard Fletcher, at the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, at Fotheringay Castle, “knelt down on the scaffold steps and started to pray out loud and at length, in a prolonged and rhetorical style as though determined to force his way into the pages of history”. He cried out at her death, “So perish all the Queen’s enemies!”

Richard Fletcher died shortly after falling out of favour with the Queen, over a marriage she had advised against. He appears to have been partly rehabilitated before his death in 1596 but he died substantially in debt. The upbringing of John Fletcher and his seven siblings was entrusted to his paternal uncle Giles Fletcher, a poet and minor official. His uncle’s connexions ceased to be a benefit and may even have become a liability after the rebellion of Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, who had been his patron. Fletcher appears to have entered Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, in 1591, at the age of eleven. It is not certain that he took a degree but evidence suggests that he was preparing for a career in the church. Little is known about his time at college, but he evidently followed the path previously trodden by the University wits before him, from Cambridge to the burgeoning commercial theatre of London.

Collaborations with Beaumont

In 1606, he began to appear as a playwright for the Children of the Queen’s Revels, then performing at the Blackfriars Theatre. Commendatory verses by Richard Brome in the Beaumont and Fletcher 1647 folio place Fletcher in the company of Ben Jonson; a comment of Jonson’s to Drummond corroborates this claim, although it is not known when this friendship began. At the beginning of his career, his most important association was with Francis Beaumont. The two wrote together for close on a decade, first for the children and then for the King’s Men. According to an anecdote transmitted or invented by John Aubrey, they also lived together (in Bankside), sharing clothes and having “one wench in the house between them”. This domestic arrangement, if it existed, was ended by Beaumont’s marriage in 1613 and their dramatic partnership ended after Beaumont fell ill, probably of a stroke, the same year.

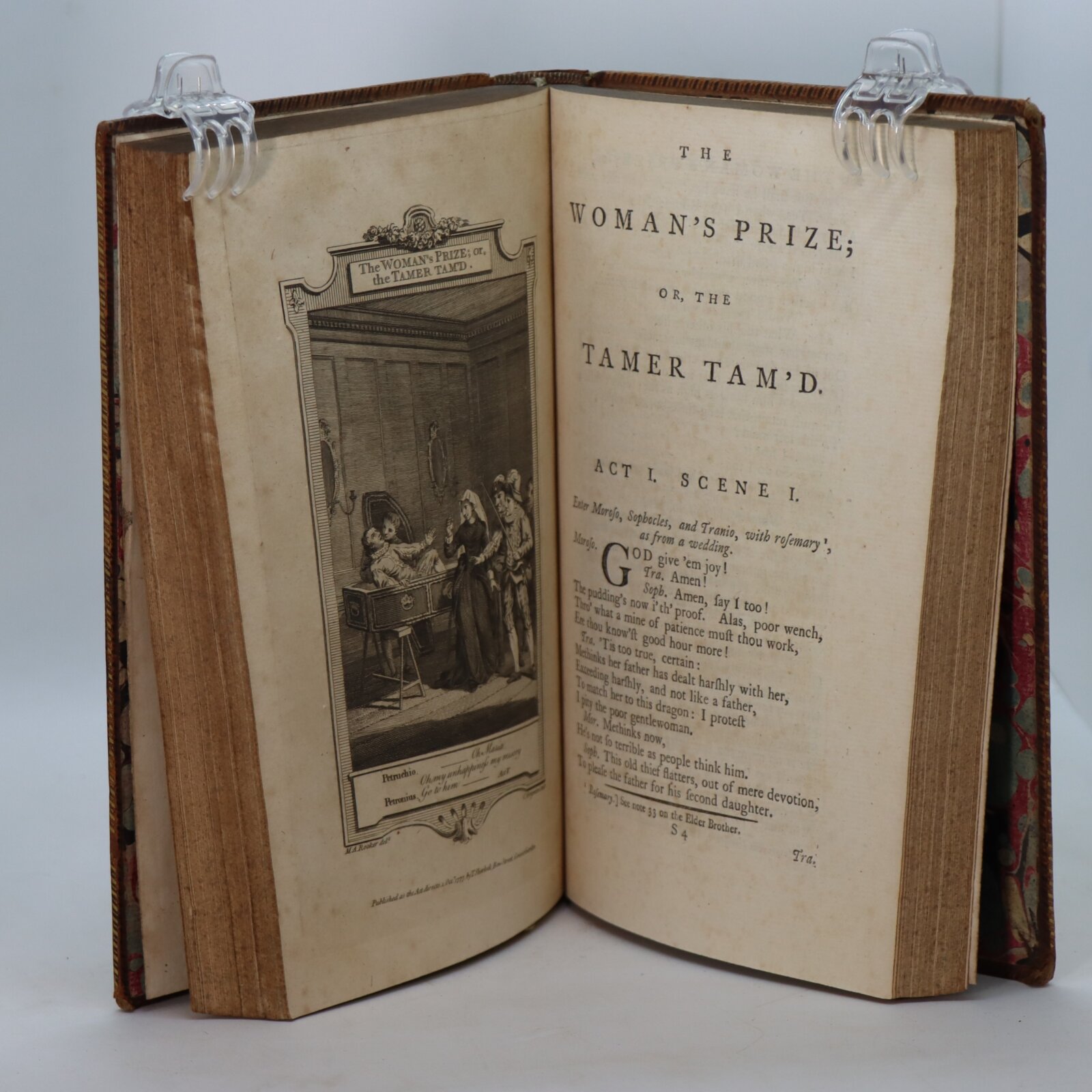

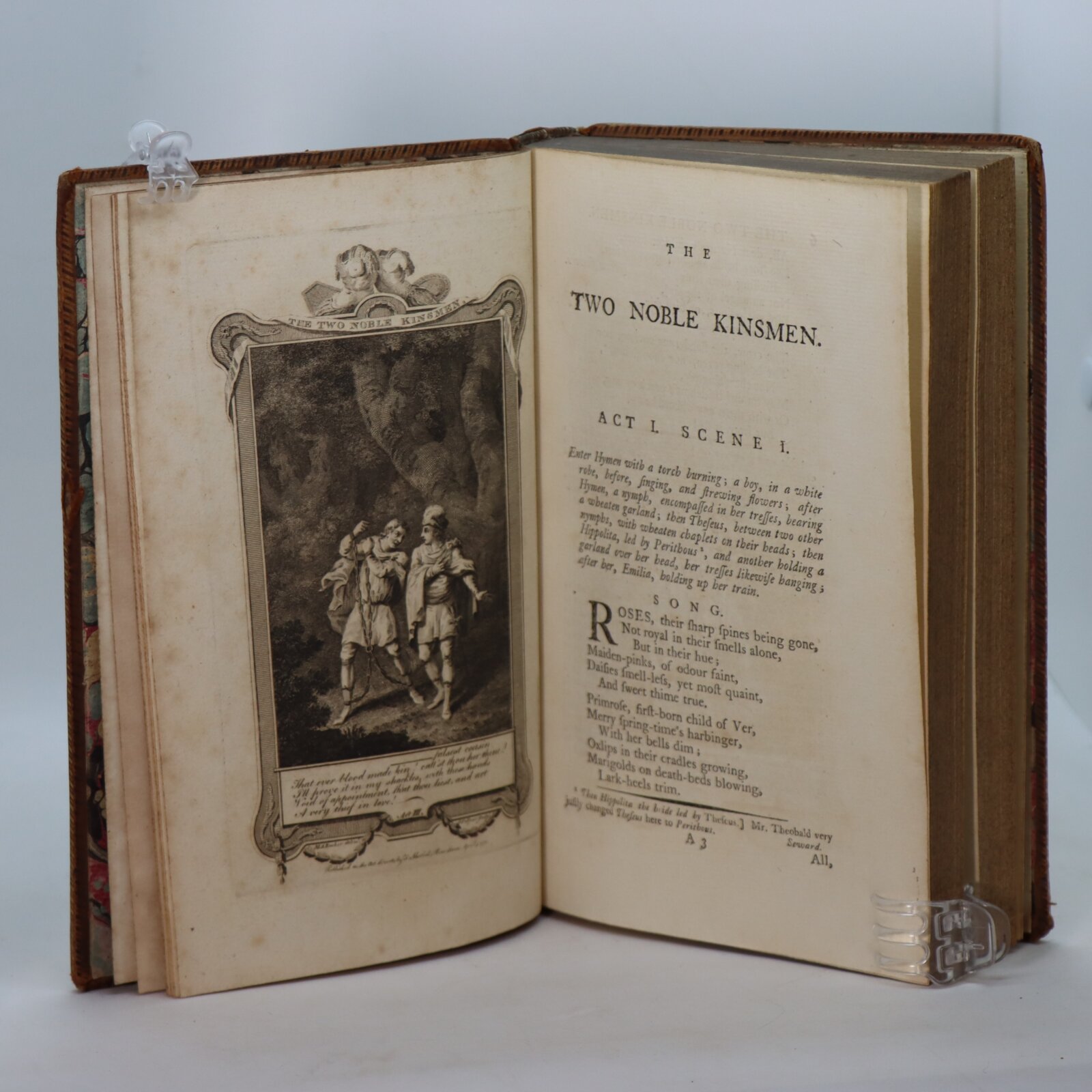

Successor to Shakespeare

By this time, Fletcher had moved into a closer association with the King’s Men. He collaborated with Shakespeare on Henry VIII, The Two Noble Kinsmen and the lost Cardenio, which is probably (according to some modern scholars) the basis for Lewis Theobald’s play Double Falsehood. A play he wrote singly around this time, The Woman’s Prize or the Tamer Tamed, is a sequel to The Taming of the Shrew. In 1616, after Shakespeare’s death, Fletcher appears to have entered into an exclusive arrangement with the King’s Men similar to Shakespeare’s. Fletcher wrote only for that company between the death of Shakespeare and his death nine years later. He never lost his habit of collaboration, working with Nathan Field and later with Philip Massinger, who succeeded him as house playwright for the King’s Men. His popularity continued throughout his life; during the winter of 1621, three of his plays were performed at court. He died in 1625, apparently of the plague. He seems to have been buried in what is now Southwark Cathedral, although the precise location is not known; there is a reference by Aston Cockayne to a common grave for Fletcher and Massinger (also buried in Southwark). What is more certain is that two simple adjacent stones in the floor of the Choir of Southwark Cathedral, one marked ‘Edmond Shakespeare 1607’ the other ‘John Fletcher 1625’ refer to Shakespeare’s younger brother and the playwright. His mastery is most notable in two dramatic types, tragicomedy and comedy of manners.

William Shakespeare (bapt. 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world’s greatest dramatist. He is often called England’s national poet and the “Bard of Avon” (or simply “the Bard”). His extant works, including collaborations, consist of some 39 plays,154 sonnets, three long narrative poems, and a few other verses, some of uncertain authorship. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright. They also continue to be studied and reinterpreted.

Shakespeare was born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna and twins Hamnet and Judith. Sometime between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, later known as the King’s Men. At age 49 (around 1613), he appears to have retired to Stratford, where he died three years later. Few records of Shakespeare’s private life survive; this has stimulated considerable speculation about such matters as his physical appearance, his sexuality, his religious beliefs and whether the works attributed to him were written by others.

Shakespeare produced most of his known works between 1589 and 1613. His early plays were primarily comedies and histories and are regarded as some of the best work produced in these genres. He then wrote mainly tragedies until 1608, amongst them Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth, all considered to be among the finest works in the English language. In the last phase of his life, he wrote tragicomedies (also known as romances) and collaborated with other playwrights.

Many of Shakespeare’s plays were published in editions of varying quality and accuracy in his lifetime. However, in 1623, two fellow actors and friends of Shakespeare’s, John Heminges and Henry Condell, published a more definitive text known as the First Folio, a posthumous collected edition of Shakespeare’s dramatic works that included all but two of his plays. Its Preface was a prescient poem by Ben Jonson that hailed Shakespeare with the now famous epithet: “not of an age, but for all time”.

Benjamin Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson’s artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for the satirical plays Every Man in His Humour (1598), Volpone, or The Fox (c. 1606), The Alchemist (1610) and Bartholomew Fair (1614) and for his lyric and epigrammatic poetry. “He is generally regarded as the second most important English dramatist, after William Shakespeare, during the reign of James I.”

Jonson was a classically educated, well-read and cultured man of the English Renaissance with an appetite for controversy (personal and political, artistic and intellectual) whose cultural influence was of unparalleled breadth upon the playwrights and the poets of the Jacobean era (1603–1625) and of the Caroline era (1625–1642).

His ancestors spelled the family name with a letter “t” (Johstone or Johnstoun). While the spelling had eventually changed to the more common “Johnson”, the playwright’s own particular preference became “Jonson”.

Nathan Field (also spelled Feild occasionally; 17 October 1587 – 1620) was an English dramatist. He was also an actor. His father was the Puritan preacher John Field, and his brother Theophilus Field became the Bishop of Llandaff. One of his brothers, named Nathaniel, often confused with the actor, became a printer. Nathan’s father passionately opposed London’s public entertainments: he delivered a sermon which attributed Divine judgment to the collapse of the public seating area, during a bear baiting on a Sunday, at Beargarden in 1583, which resulted in several deaths. Nathan presumably did not intend a career in the theatre; he was a student of Richard Mulcaster at St. Paul’s School in the late 1590s. At some point before 1600, he was impressed by Nathaniel Giles, the master of Elizabeth’s choir and one of the managers of the new troupe of boy players at Blackfriars Theatre, called alternately the Children of the Chapel Royal and the Blackfriars Children. He remained in this profession for the remainder of his life, later adding to it the profession of a playwright. John Field was buried on 26 March 1588.

When John Field died, he left seven children, of whom the eldest was only seventeen. He left all his property to his wife, Joan. The first child was a daughter, Dorcas, baptized on 7 May 1570. The first son was baptized on 4 January 1572 and was named after his father, John. Theophilus was baptized on 22 January 1574, Jonathan on 13 May 1577, Nathaniel on 13 June 1581, Elizabeth on 2 February 1583 and Nathan on 17 October 1587. Little is known of the two daughters: Dorcas was married to Edward Rice on 9 November 1590; Elizabeth was buried at St. Anne, Blackfriars, on 14 June 1603, when she had just reached twenty, the age at which Dorcas married. We know nothing of the life of John Field, junior. Jonathan Field, who died in 1640. Theophilus followed his father’s profession. He married and in his will left all his possessions to his wife, Alice. He died on 2 June 1636 and was buried in Hereford Cathedral.

As a member of the Children of the Queen’s Revels, Field acted in the innovative drama staged at Blackfriars in the first years of the 17th century. Cast lists associate him with Ben Jonson’s Cynthia’s Revels (1600) and The Poetaster (1601); a 1641 quarto associated him with George Chapman’s Bussy D’Ambois.

Later in the decade, he performed in Epicoene and, perhaps, played Humphrey in Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle. During the same years, he wrote commendatory verses for Jonson’s Volpone and Catiline, and for John Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess.

Field was presumably also among those of the children’s company briefly imprisoned for the official displeasure occasioned by Eastward Hoe and John Day’s The Isle of Gulls; the latter imprisonment was in Bridewell Prison.

Field stayed with a children’s company until 1613, his twenty-sixth year. He appears to be the only one of the boy actors of 1600 to remain with the Blackfriars troupe when, in 1609, Philip Rosseter and Robert Keysar assumed control of the company. In this company, he performed in the theatre in Whitefriars and, frequently, at court, in plays such as Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Coxcomb. From the latter years of this period come the first of his plays: A Woman is a Weathercock and The Honest Man’s Fortune (the latter with Fletcher and Philip Massinger).

In 1613, Rosseter combined his company with the Lady Elizabeth’s Men, managed by Philip Henslowe. Performing at the Swan Theatre and Hope Theatre, Field acted in Thomas Middleton’s A Chaste Maid in Cheapside and Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair. For the latter play, in which he may have performed as Cokes or Littlewit, he received payment for the company after a performance at court. These years witnessed some degree of tumult; Henslowe’s business practices resulted in his actors’ drawing up certain “articles of grievance” against him, and Rosseter’s attempt to build a new private theatre (Porter’s Hall) in Blackfriars was blocked by the city and Privy Council. This period ended when Henslowe died, Rosseter abandoned his plans, and Lady Elizabeth’s Men briefly merged and then separated from Prince Charles’s Men, thereafter touring in the country. For Field, the period had a presumably more satisfactory end: by late 1616, he had joined the King’s Men.

With the King’s Men, Field seems to have performed as Voltore in Volpone and as Face in The Alchemist. It is not clear what other parts he played; an epigram, produced by John Payne Collier, that associated the actor with the role of Othello is an apparent forgery. Edmond Malone supposed that Field played women’s roles with the company; O. J. Campbell, however, suggests that he played young second leads. Of course he acted in a number of Fletcher’s plays, as well as Shakespeare’s; presumably he also acted in his own Amends for Ladies (printed 1618, though probably written earlier), and in The Fatal Dowry, which he wrote with Philip Massinger. Field died sometime between May 1619 and August 1620.

Scholars and critics have argued for authorial contributions from Field in a number of plays of his era, most commonly in Four Plays in One, The Honest Man’s Fortune, The Queen of Corinth and The Knight of Malta, four dramas in the canon of Fletcher and his collaborators.

Field had a contemporary reputation as a ladies’ man; gossip reported by William Trumbull charges him with a child of the Countess of Argyll. A portrait believed to be of Field can be seen at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, UK, in which he is depicted as a melancholy figure with hand on heart. It has been said that this painting may be one of the first depictions of an actor “in character”. The portrait artist is unknown, but some believe that it was painted by William Larkin.

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (baptised 26 February 1564 – 30 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the “many imitations” of his play Tamburlaine, modern scholars consider him to have been the foremost dramatist in London in the years just before his mysterious early death. Some scholars also believe that he greatly influenced William Shakespeare, who was baptised in the same year as Marlowe and later succeeded him as the pre-eminent Elizabethan playwright. Marlowe was the first to achieve critical reputation for his use of blank verse, which became the standard for the era. His plays are distinguished by their overreaching protagonists. Themes found within Marlowe’s literary works have been noted as humanistic with realistic emotions, which some scholars find difficult to reconcile with Marlowe’s “anti-intellectualism” and his catering to the prurient tastes of his Elizabethan audiences for generous displays of extreme physical violence, cruelty, and bloodshed.

Events in Marlowe’s life were sometimes as extreme as those found in his plays. Reports of Marlowe’s death in 1593 were particularly infamous in his day and are contested by scholars today owing to a lack of good documentation. Traditionally, the playwright’s death has been blamed on a long list of conjectures, including a vicious barroom fight, blasphemous libel against the church, homosexual intrigue, betrayal by another playwright, and espionage from the highest level: the Privy Council of Elizabeth I. An official coroner’s account of Marlowe’s death was only revealed in 1925, but it did little to persuade all scholars that it told the whole story, nor did it eliminate the uncertainties present in his biography.

English Renaissance theatre, also known as Renaissance English theatre and Elizabethan theatre, refers to the theatre of England between 1558 and 1642. This is the style of the plays of William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson. The term English Renaissance theatre encompasses the period between 1562—following a performance of Gorboduc, the first English play using blank verse, at the Inner Temple during the Christmas season of 1561—and the ban on theatrical plays enacted by the English Parliament in 1642. The phrase Elizabethan theatre is sometimes used, improperly, to mean English Renaissance theatre, although in a strict sense “Elizabethan” only refers to the period of Queen Elizabeth’s reign (1558–1603). English Renaissance theatre may be said to encompass Elizabethan theatre from 1562 to 1603, Jacobean theatre from 1603 to 1625, and Caroline theatre from 1625 to 1642.

Along with the economics of the profession, the character of the drama changed towards the end of the period. Under Elizabeth, the drama was a unified expression as far as social class was concerned: the Court watched the same plays the commoners saw in the public playhouses. With the development of the private theatres, drama became more oriented towards the tastes and values of an upper-class audience. By the later part of the reign of Charles I, few new plays were being written for the public theatres, which sustained themselves on the accumulated works of the previous decades.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend