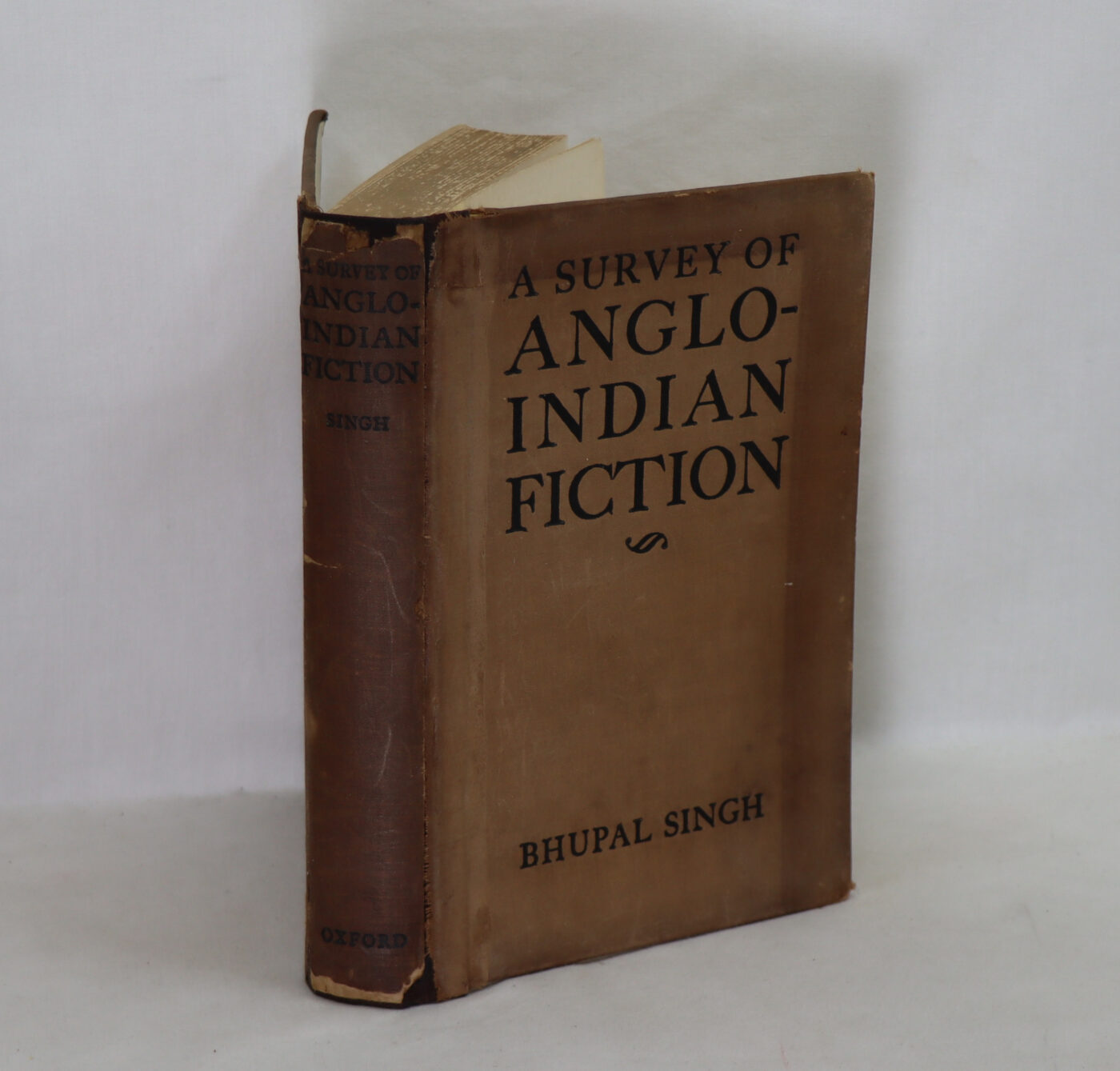

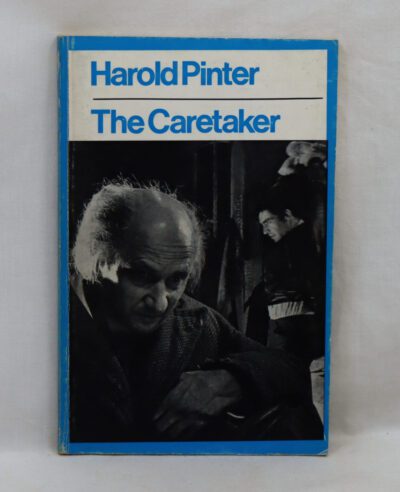

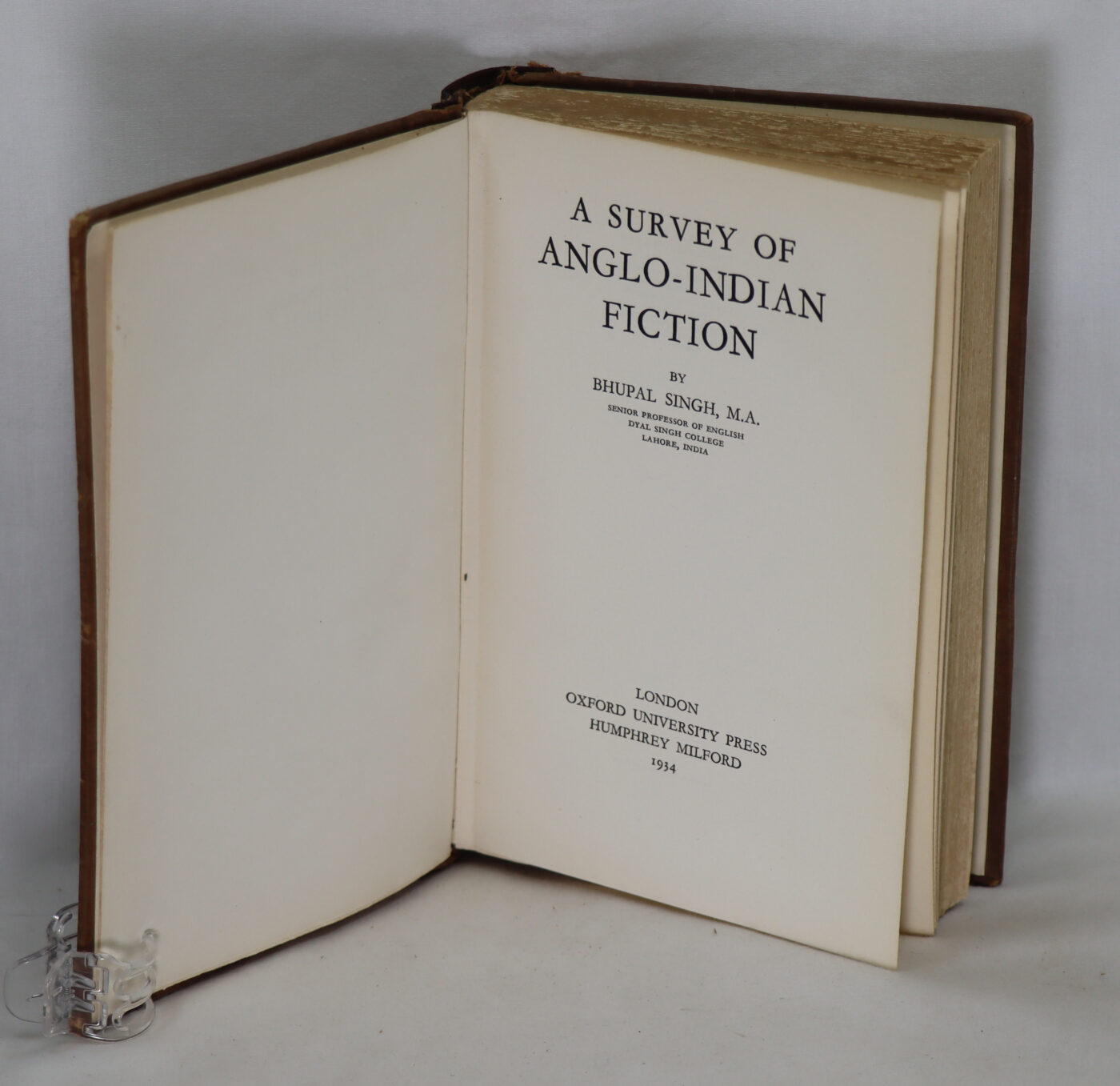

A Survey of Anglo-Indian Fiction.

By Bhupal Singh

Printed: 1934

Publisher: Oxford University Press. London

| Dimensions | 14 × 20 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 14 x 20 x 3

Condition: Good (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Item information

Description

Tan cloth binding with black title on the (RE-BACKED) spine and front board.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

This extremely rare first edition milestone book marks the beginning of the growing academic interest in this fascinating study.

For conditions, please view our photographs. A nice clean extremely rare copy from the library gathered by the famous Cambridge Don, computer scientist, food and wine connoisseur, Jack Arnold LANG.

An analysis of Anglo-Indian fiction gives an insight into how the English viewed the population of India at the time of the British Raj. The novels of colonial India provide a mirror for perceiving attitudes which are now part of India’s history. It can therefore be argued that Anglo-Indian fiction is a criticism of the life of English men and women in India, and of Indians before partition. Originally published in 1934, this book analyses this criticism and provides a critical consensus of the whole of fictional writing in English during the 150 years from Warren Hastings until the British withdrawal from India.

The structure of Bhupal Singh’s ‘A Survey of Anglo-Indian Fiction’ is:

Chapter I — Introductory

3. Main Ingredients of a Novel of Anglo-Indian Life

4. Early Anglo-Indians

5. ‘Qui Hai’ of the Early Nineteenth Century

6. ‘Competition Wallah’

7. Anglo-India To-day

Chapter II — Meadows Taylor and Other Predecessors of Kipling

8. Beginnings of Anglo-Indian Fiction

9. W. B. Hockley

10. Scott’s ‘The Surgeon’s Daughter’

11. Dickens and India

12. Thackeray and India

13. Meadows Taylor

14. Other Novelists, 1834-53

15. W. D. Arnold

16. Post-Mutiny Novels, 1859-69

17. Precursors of Kipling — Phil Robinson, Prichard, Cunningham, and Alexander Allardyce

Chapter III — Rudyard Kipling — A Survey of His Indian Stories

18. Kipling’s Anglo-Indian Stories

19. Kipling’s Indian Stories

20. Kim and The Naulahka

21. Kipling’s Limitations

22. Kipling’s Knowledge of Indian Women

Chapter IV — Rudyard Kipling and His School

23. Influence of Kipling on Short-story Writers

24. Mrs. Flora Annie Steel

25. Mrs. Alice Perrin

26. Otto Rothfeld and ‘Andrul’

27. Edmund Candler

28. Sir Edmund Cox, Herbert Sherring, ‘Richard Dehan’, Ethel M. Dell, A. T. Marris, and John Eyton

29. ‘Afghan’

30. The Ranee of Sarawak, Maud Diver, and Mrs. Savi

31. Hilton Brown

32. Miss Mayo, Mrs. Beck, and Mr. Humfrey Jordan

33. Kipling and his Imitators

34. Foran, Somers, and Craig

35. Kim’s Cousins

36. S. K. Ghosh

Chapter V — Novels of Anglo-Indian Life

37. Mrs. B. M. Croker

38. Mrs. Maud Diver

39. ‘John Travers’ (Mrs. G. H. Bell)

40. Mrs. Alice Perrin

41. Mrs. E. W. Savi

42. Shelland Bradley

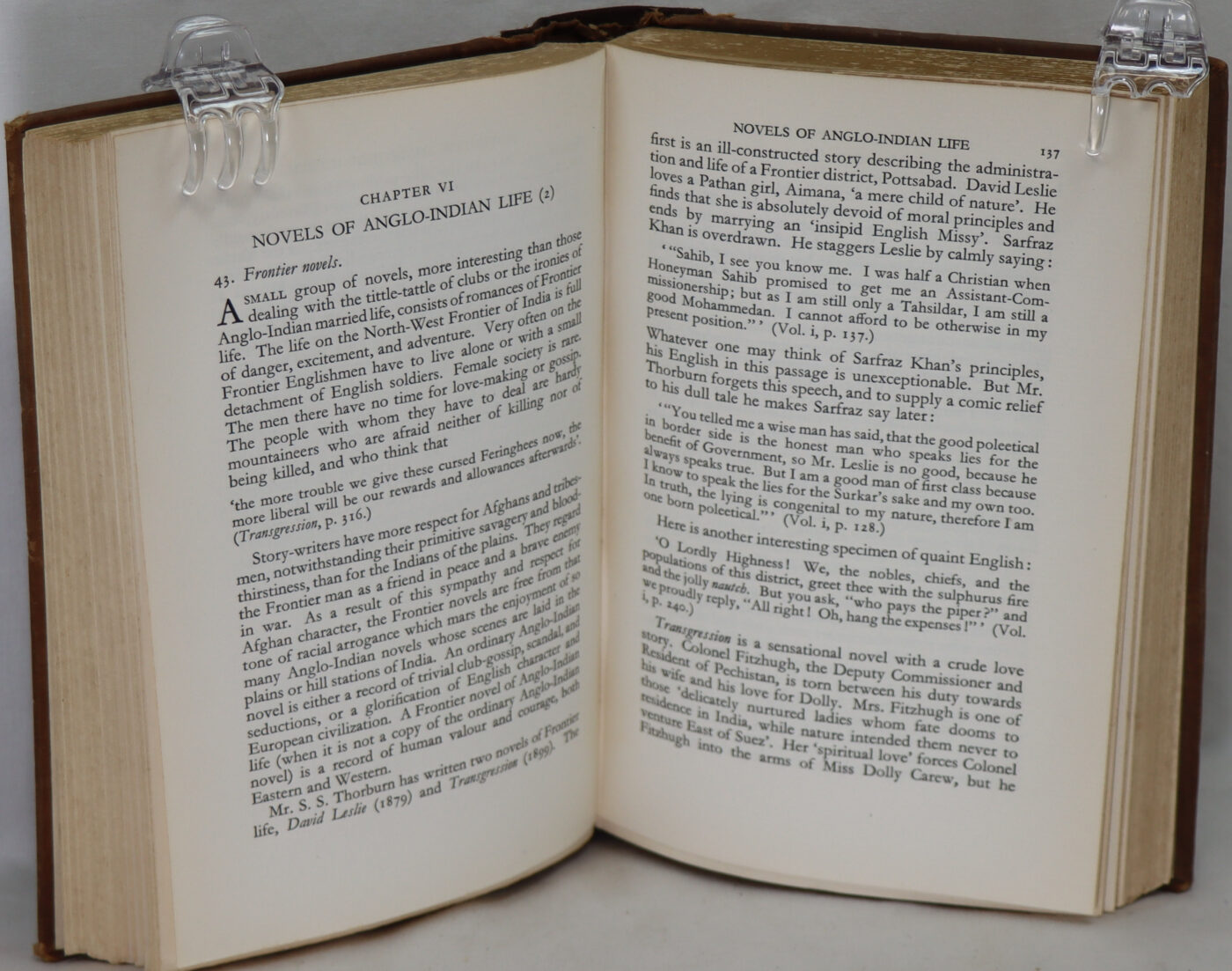

Chapter VI — Novels of Anglo-Indian Life (2)

43. Frontier Novels

44. Sir Francis Younghusband

45. ‘Afghan’, Michael John, John Delbridge, and Mrs. T. Pennell

46. Novels of Anglo-Burmese Life

47. Novels of Missionary Life

48. Life in the Moffusil. Miss Mountain and Mr. Hilton Brown

Chapter VII — Novels of Mixed Marriages and Eurasian Life

50. Novels of Eurasian Life

51. Eurasian Beauty

52. Henry Bruce

53. The Ranee of Sarawak

Chapter VIII — Indian Politics and Anglo-Indian Novels

54. Beginnings of Indian Nationalism

55. Edmund Candler and Indian unrest

56. Novels of the Second Period of Indian Nationalism

57. Novels of the Third Period

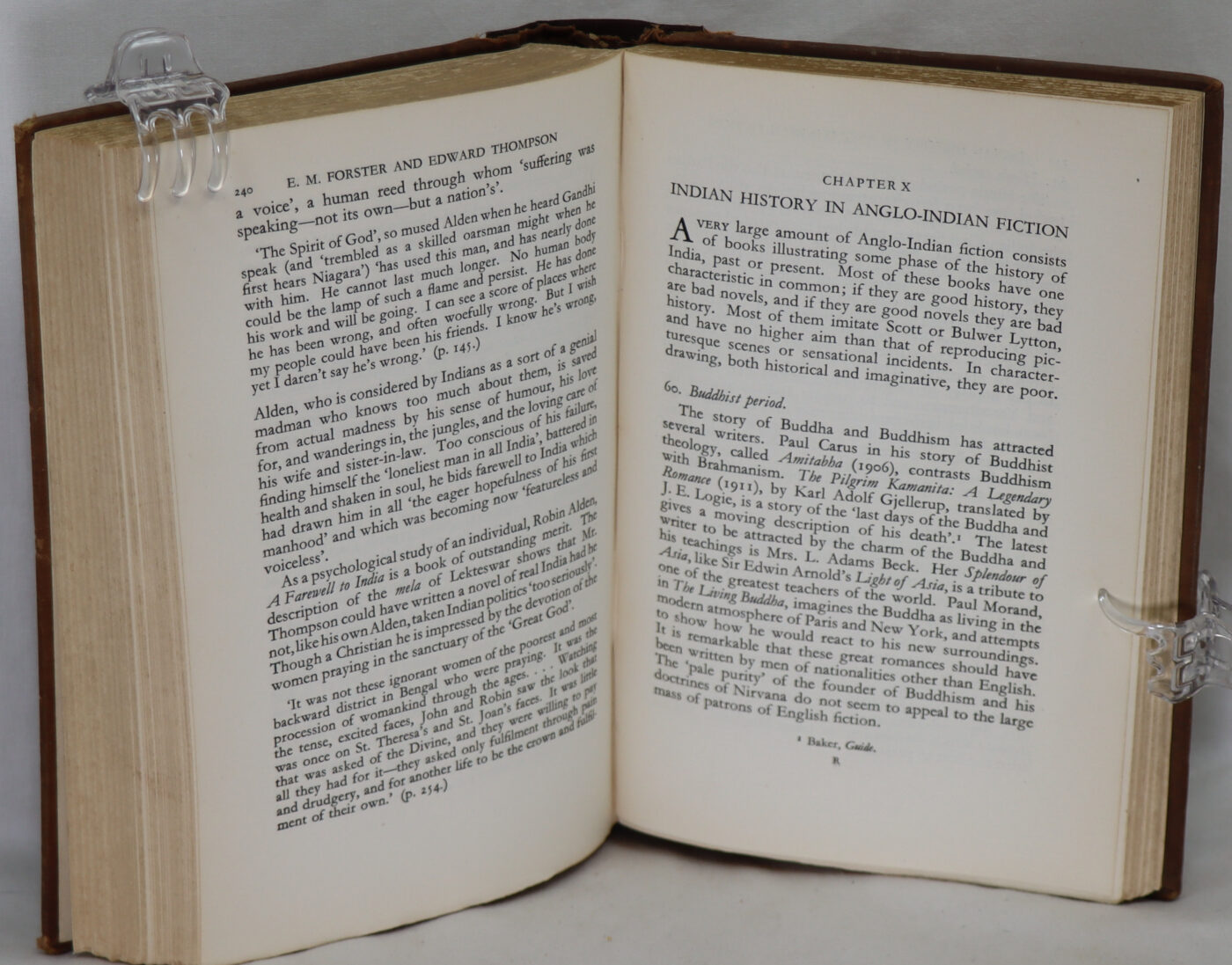

Chapter IX — E. M. Forster and Edward Thompson

58. ‘A Passage to India’

59. Mr. Edward Thompson

Chapter X — Indian History in Anglo-Indian Fiction

60. Buddhist Period

61. Hindu Period

62. Moghul Period

63. Seventeenth Century, Aurangzeb and Shivaji

64. East India Company

65. Begum Somru

66. Wars in the Nineteenth Century

67. Novels of the Indian Mutiny

68. Siege of Delhi, and Mrs. Steel

69. Annexation of Upper Burma — Miss Tennyson Jesse

Chapter XI — The Mysterious East or Anglo-Indian Mystery Novels

70. Jewel Hunting

71. Novels of the Occult

72. Novels Dealing with Conspiracy against the British Raj

Chapter XII — East as Seen by West or Anglo-Indian Novels of Indian Life

73. Mrs. F. E. Penny

74. Mr. Edmund White

75. Mr. R. J. Minney

76. Conclusion

In the Conclusion of ‘A Survey of Anglo-Indian Fiction’ Bhupal Singh explains:

India has struck Anglo-Indian novelists in a variety of ways. Some of them are attracted by her picturesqueness, some by her strange contradictions, and a few by her mystery. The general note, however, is one of disillusionment and disappointment. To most Englishmen and Englishwomen in England, as Mr. John Eyton puts it, India is merely ‘a pear-shaped lump on the map coloured red’.Sir Henry Cunningham is the earliest writer to strike this note of discontent.

‘“The India of sentiment and nonsense,” said Montem, “is,—and always will be the fashion—the India that Burke flooded with bombast and Macaulay with antithesis—the India that Stain writes pamphlets about and Frontinbras sonnets—the India that never was, and never will be.”’ (The Cœruleans, p. 100.)

He actually finds India ‘one of the dullest, most tedious, unpicturesque affairs you can conceive’.

Norah K. Strange, in Mistress of Ceremonies, has a fling at old Portuguese, Dutch, and Italian travellers who depicted India as a land flowing with milk and honey—‘a land in which prosperous towns, luxurious gardens and goodly estates were to be found, while the ports did a busy trade in copper, quicksilver, vermilion, coral, alum, ivory, and spices.’ Mr. Campbell is disappointed with India, for she ‘had failed to fulfil the mystic promise’ with which she had lured him. Similarly, to Kathleen in Mrs. Savi’s The Daughter-in-Law, India was ‘the land of her dreams— the land of warmth, sunshine and luxury, of elephants, palm trees and pagodas; picturesque with colour and full of unreality!’ but when in India she failed to find the poetry and romance that she had read so much about in books. Also Miss Rendell, who ‘had a romantic notion about the East’, suffers disillusionment when she sees the country. Mrs. Savi ridicules the stories in which India is painted ‘in sunset tints’ and which omit ‘all the noxious things’ whose mention might lower the charm of the ‘artificial East’. Mr. Newcomen writes about ‘the glittering, shiny, sumptuous, seductive East that one reads about so often but seldom sees’. Mr. Y. Endrikar finds himself in India ‘up against things you can’t understand’, and discovers that the ‘glamour of the gorgeous East wears off’ after the first voyage. To Mr. K. M. Edge India is a land of ‘passion and sorrow and stress’; to ‘John Travers’ the luxurious East is a fraud, and the vast world of Ind, ‘a world of contradictions’,

‘where the twice born, the Brahmin whose curse is perdition, can be at the same time a peasant soldier, poor and unknown—where the sweeper is called in irony “prince”! . . . where the Sikh may not smoke and the Musalman may not drink; where the Musalman must eat of flesh that has had its throat cut in the name of God and the Sikh may only eat of meat that has been beheaded, where beef is pollution to one and pig is horror unutterable to another.’ (Sahib-log, p. 88.)

This widespread feeling of disgust among Anglo-Indian writers is the result of several causes. In the first place, they pitch their expectations too high. The India of reality must be different from the India of their imagination. Secondly, the very vastness and variety of India paralyses their power of understanding. In spite of their long stay, their knowledge of India remains superficial. What can mem-sahib do—and it is she who has written such a large number of novels of India—possibly know of India—under the peculiar conditions of Anglo-Indian life? Even if prestige and racial pride do not distort one’s outlook, no generalization about India can be correct. Finally, it has to be admitted that the way in which the vast majority of the people live is uninspiring. The great and grinding poverty of the masses is responsible for this.

Still there are some writers, though their number is small, who retain their illusions about India. Mrs. B. M. Croker is touched by the ‘groups of picturesque women, surrounding that centre of attraction, the well, clad in bright yellow garments, confined round the waist with broad massive silver belts, their hair ornamented or padded out with fragrant blossoms’.Miss Frances M. Peard has seen very little more of true India than wayside railway stations

‘thronged with patient brown people moving about or squatting on the ground, with stately women in “sorris” of chocolate or blue, their silver armlets gleaming, their brass waterpots at their feet, and running from one to the other, their copper-coloured imps with nothing particular on. Outside the gate a tonga all bright colours and gaiety, and drawn by a small cream-coloured bullock.’ (The Flying Months, p. 252.)

Mr. Gamon, while describing the India of the eighteenth century, is filled with ‘a strange sense of longing and melancholy’ as he breathes ‘the stagnant air’, heavy with the voluptuous odour of jasmine, a perfume ‘which seems redolent of all the mystery and romance of this land’. Baroness Alexander de Soucanton hears the call of this ‘great mysterious land’, she admires her ‘wonderful Eastern nights’, and speaks of her sun as ‘a fierce God indeed, in all his glory’; Mrs. Barbara Wingfield-Stratford, like her Beryl, feels a ‘new, warm flood of sympathy’ for India. She admires

‘the saris of the women, red, orange, blue; the bare brown limbs of the children, the hum of life and the rhythmic soothing beat of the tom-tom, the weirdly fascinating thrill of the snake-charmer’s pipe, the discordantly melodious clang of temple bells and blare of conches at sunset’, (p. 136.)

Even the great monotonous plains of India have ‘a subtle charm for her eyes’. In their ‘grey-bronze serene endlessness’, they give her

‘a half-sad, half-satisfying sense of a completeness and unchangingness that yet seem to her but yearning after something even more’, (p. 137.)

Miss Joan Conquest condemns her countrymen who ‘mistake the eastern courtesy and poetry of movement for obsequiousness and humility’. Among the ‘highly coloured, bejewelled pictures’ which India places before westerners, she sees ‘the terrible root’ of Indian courtesy and poetry—the root of patience

‘with its tentacles ever twining and twisting through the eastern mind, causing the very old to die placidly with a smile on their shrivelled lips, and the young to envisage plague, pestilence, and famine with a mere lifting of the shoulder’. (Leonie of the Jungle, p. 50.)

Even Mrs. E. W. Savi is occasionally touched by ‘the India of wide spaces and slow movement, and a peace upon all that was infinitely restful and calm’.Miss Irene Burn admires in India at least ‘the freedom of having a bathroom to oneself’.

The study of Anglo-Indian fiction suggests that Englishmen have a very poor, even contemptuous opinion of Indian character and little patience with their ‘Aryan friend’. According to Mrs. Penny, the natives of India love ‘tortuous methods’ of seeking justice. They are referred to as ‘such dirty warmints’. In another place they are likened to parrots. They love ‘a grand village quarrel’, their customs savour of the barbaric, they are all knaves, they are not ‘distinguished for delicacy of feeling’, they ‘go down hill fast when they start’, and it is emotion, not reason, which sways them. Native temperament can seldom be relied upon to do the expected thing. The belief of Hindus in the sacredness of life does not imply a ‘touching love and kindness for all animals’. They are all’lying rascals’. The Indian takes ‘a perverted delight in doing things the wrong way’. Fatalism is a habit of mind peculiar to the people of the East where the unexpected might happen at any time. The ‘natives haven’t the foggiest idea of hygiene’. They are terribly afraid of surgery, and risk gangrene before they ‘will consent to an operation’. Mr. Alastair Shannon is careful to note that Indians have ‘the age-long habit of their species’ of expectorating with grave deliberation after making a remark.

All this is very interesting. Perhaps Anglo-Indian writers who have favoured us with this delineation of our character, will admit that the population of India does not entirely consist of ‘dirty warmints’ or ‘lying rascals’. They must also have met Indians who may even be described as civilized, and Indians who do not expect, even without grave deliberation, after making a remark. But it is impossible to quarrel with writers of fiction. Anglo-Indian writers have a right to make fun of us, if it pleases them to do so. And no harm is done, provided it is understood that Anglo-Indian art is not always a faithful copy of life.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend