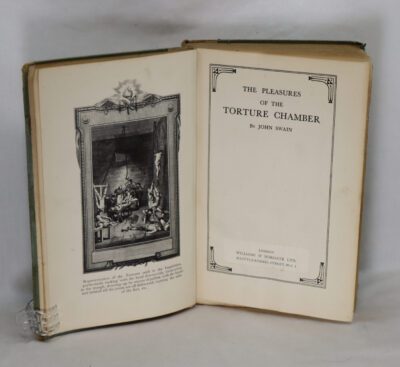

The Midnight Hour.

Printed: Circa 1820

Publisher: Ann Lemoine. Colman Street

| Dimensions | 9 × 14 × 1 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 9 x 14 x 1

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Grey cloth boards with gilt title on the front board and black calf spine.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

This chapbook has been beautifully rebound by Mr. Brian Cole.

This is a rare gothic chapbook story produced in 1808 by England’s first female chapbook publisher, Ann Lemoine who published over 400 chapbooks––small, cheaply printed booklets often disseminated among lower stations––from 1795 to 1820. Lemoine’s success in the chapbook trade was due, in part, to the integration of frontispieces (illustration preceding a title page) in her publications. Frontispieces were often associated with expensive and sophisticated volumes. At the tail-end of the eighteenth century, copper-printing became accessible due to the number of printing inventions already on the market, such as chemical relief etching and lithography (Bearden-White 69). Lemoine’s husband, Henry, purchased a copper-press in an effort to elevate the value and quality of the chapbooks which were, at that point, using woodcut illustrations. Teaming up with copperplate printer, Thomas Maiden, and bookseller, Thomas Hurst, Lemoine applied this technology after Henry was imprisoned in 1794 to form realistic images using a specialized etching technique. This technique allowed for different shades to be applied to an image to produce a life-like appearance.

Chapbook frontispiece of Voltaire’s The Extraordinary Tragical Fate of Calas, showing Jean Calas being tortured on a breaking wheel, late 18th century

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch. In early modern Europe a chapbook was a type of printed street literature. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were small, paper-covered booklets, usually printed on a single sheet folded into books of 8, 12, 16, or 24 pages. They were often illustrated with crude woodcuts, which sometimes bore no relation to the text (much like today’s stock photos), and were often read aloud to an audience. When illustrations were included in chapbooks, they were considered popular prints.

The tradition of chapbooks arose in the 16th century, as soon as printed books became affordable, and rose to its height during the 17th and 18th centuries. Many different kinds of ephemera and popular or folk literature were published as chapbooks, such as almanacs, children’s literature, folk tales, ballads, nursery rhymes, pamphlets, poetry, and political and religious tracts.

The term “chapbook” for this type of literature was coined in the 19th century. The corresponding French term is bibliothèque bleue (blue library) because they were often wrapped in cheap blue paper that was usually reserved as a wrapping for sugar. The German term is Volksbuch (people’s book). In Spain, they were known as pliegos de cordel (cordel sheets). In Spain, they were also known as pliegos sueltos, which translates to loose sheets, because they were literally loose sheets of paper folded once or twice in order to create a booklet in quarto format. Lubok is the Russian equivalent of the chapbook.

The term “chapbook” is also in use for present-day publications, commonly short, inexpensive booklets.

Chapbooks were cheap, anonymous publications that were the usual reading material for lower-class people who could not afford books. Members of the upper classes occasionally owned chapbooks, perhaps bound in leather with a personal monogram. Printers typically tailored their texts for the popular market. Chapbooks were usually between four and twenty-four pages long, and produced on rough paper with crude, frequently recycled, woodcut illustrations. They sold in the millions.

After 1696 English chapbook peddlers had to be licensed, and 2,500 of them were then authorized, 500 in London alone. In France, there were 3,500 licensed colporteurs by 1848, and they sold 40 million books annually.

The centre of the chapbook and ballad production was London, and until the Great Fire of London (1666) the printers were based around London Bridge. However, a feature of chapbooks is the proliferation of provincial printers, especially in Scotland and Newcastle upon Tyne. The first Scottish publication was the tale of Tom Thumb, in 1682.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend