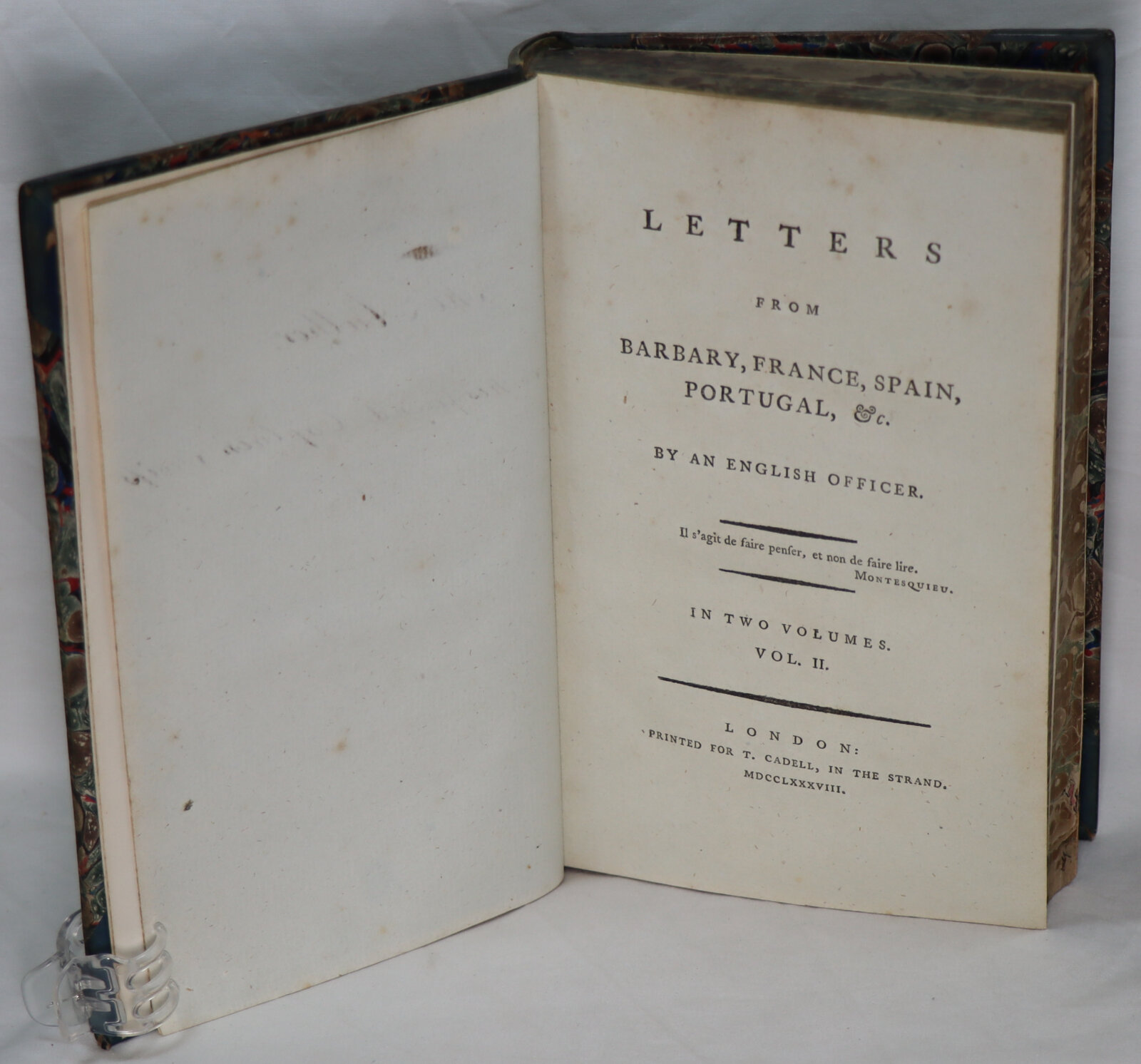

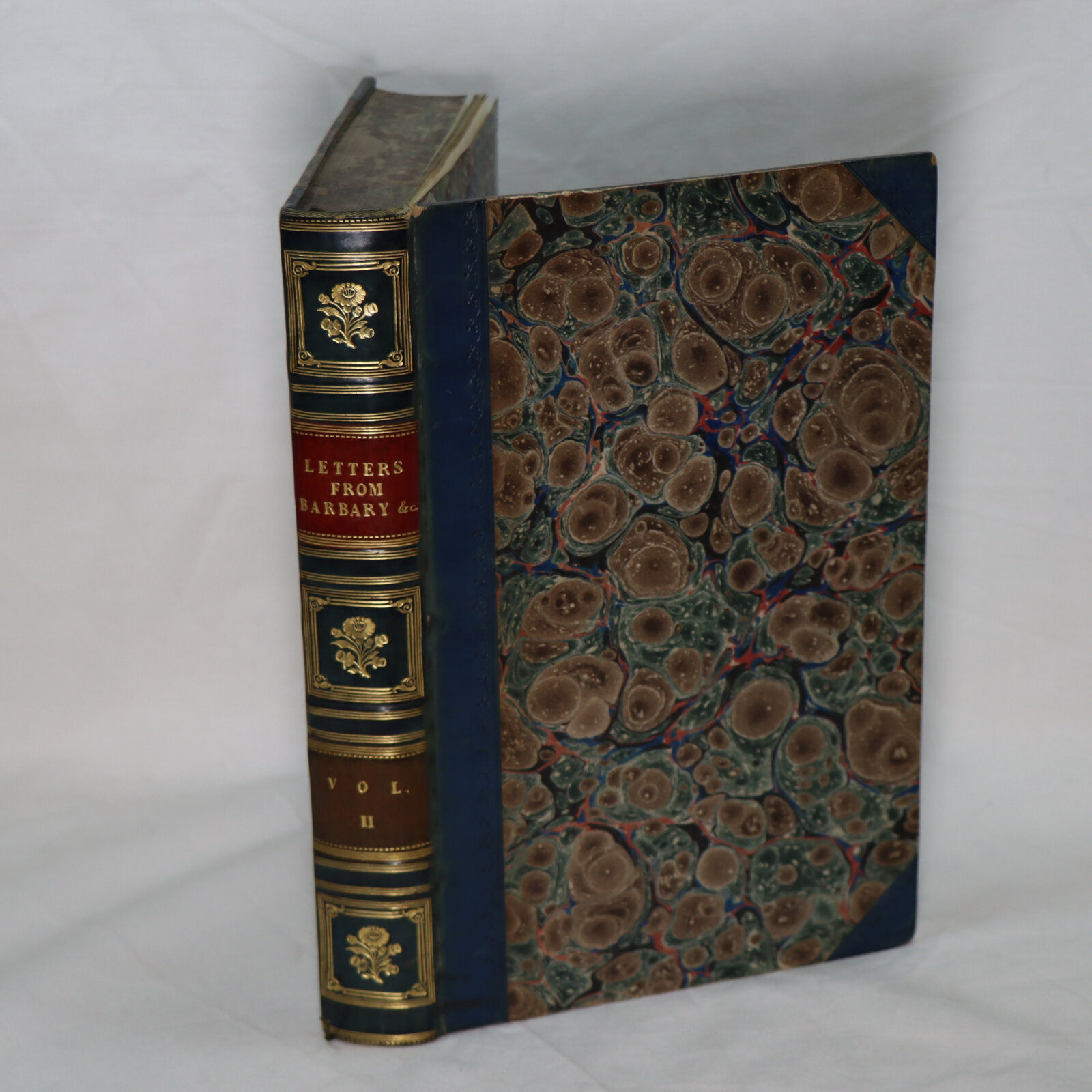

Letters from Barbary & Co. Volume II.

By 'An English Officer'

Printed: 1788

Publisher: T Cadell. London

| Dimensions | 14 × 21 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 14 x 21 x 3

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Item information

Description

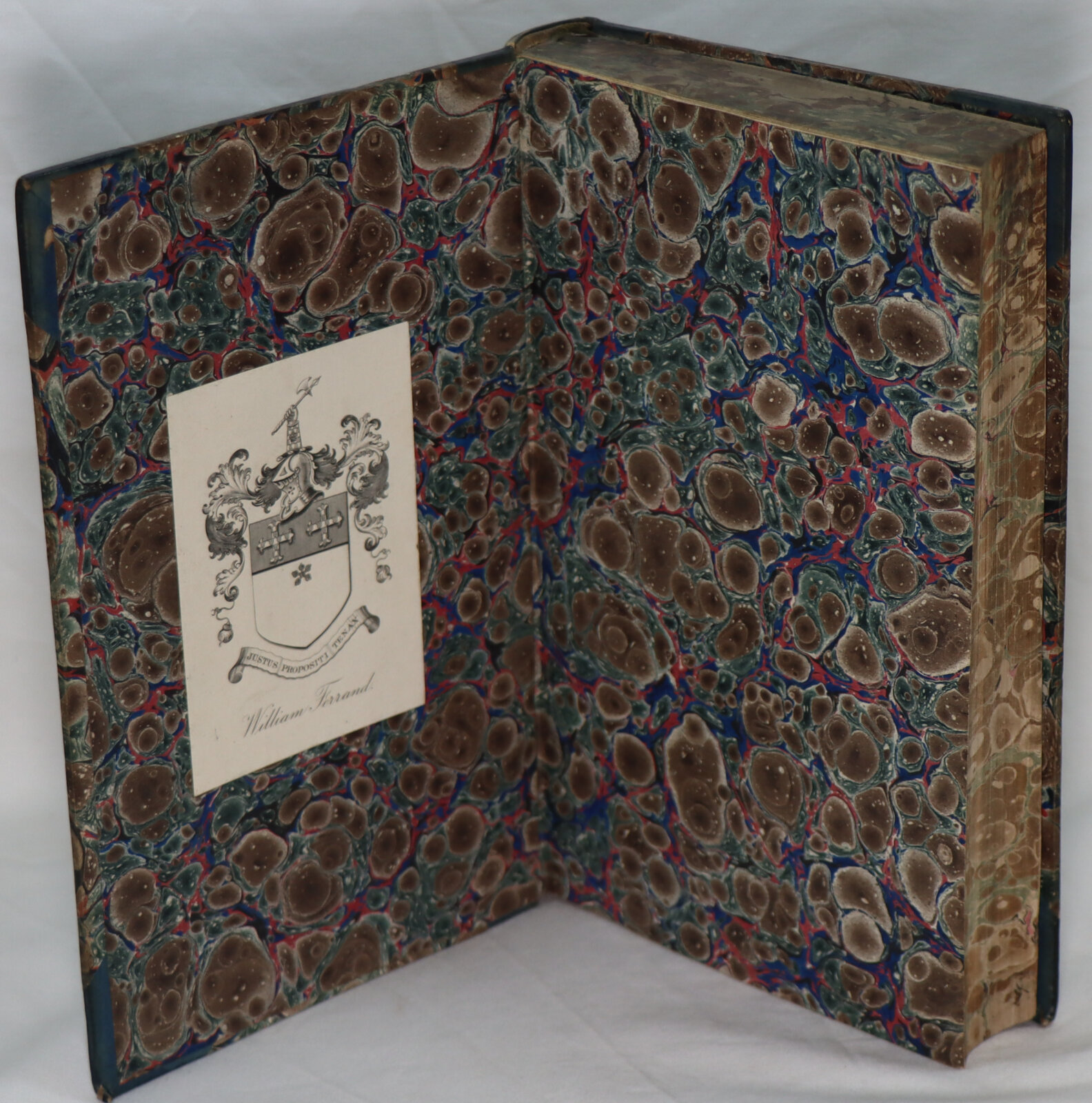

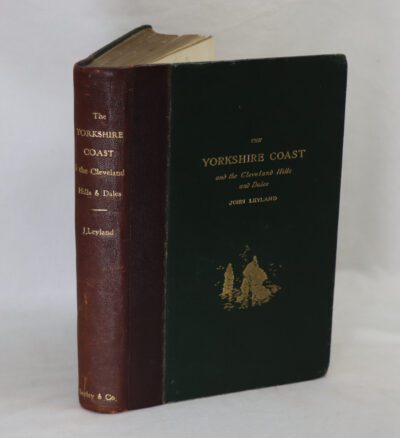

Navy calf spine with red and brown title plates, gilt decoration and title. Blue and brown marbled boards and end papers.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

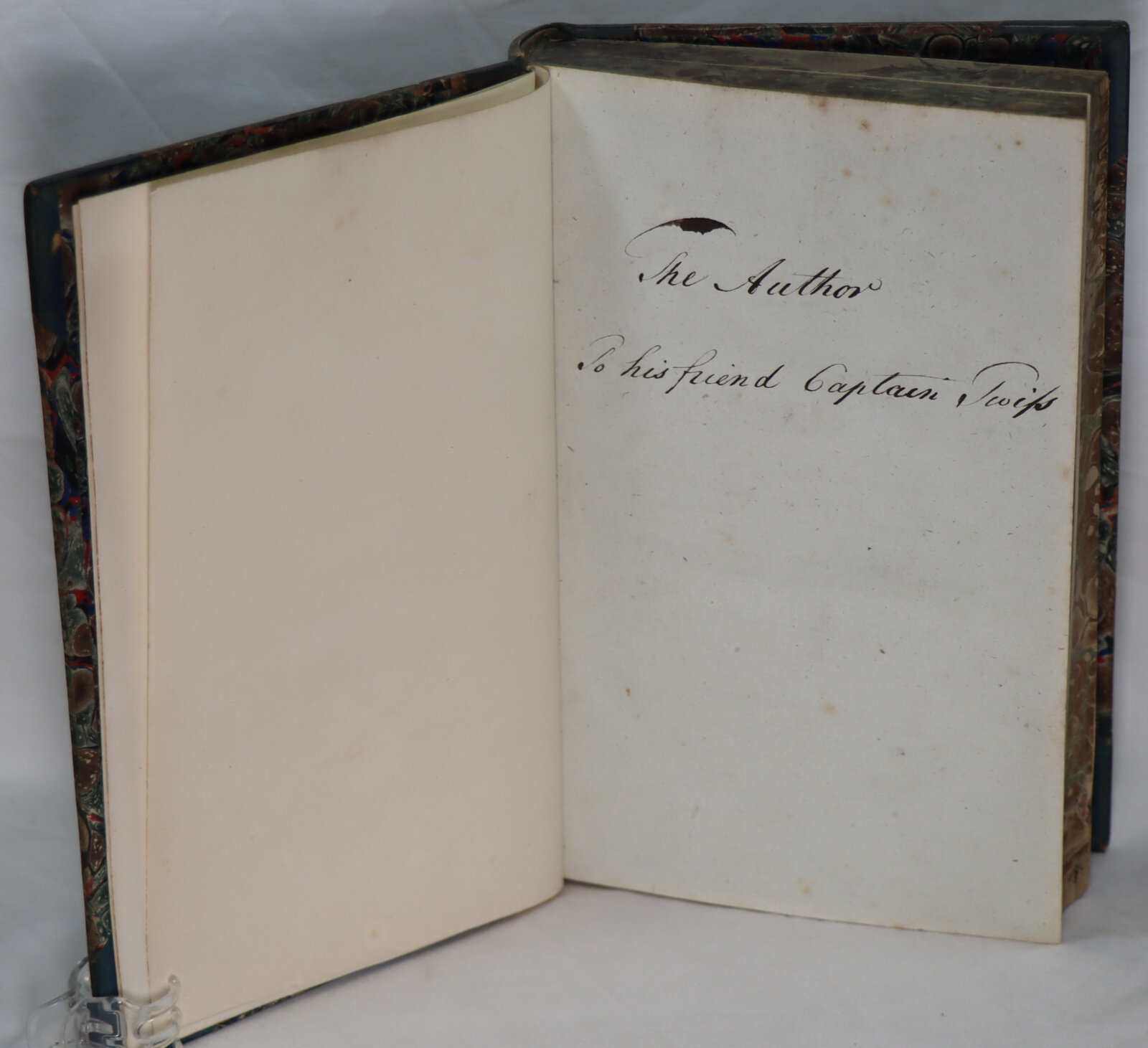

Signed by the author (Jardine, Alexander) , this is a stand alone book full of individual historic letters. A First Edition of a second volume from a two volume set.

First edition. Jardine (died. 1799), a Royal Artillery officer, was for much of his career stationed in Gibraltar, from where he conducted a mission to the sultan of Morocco, Muhammad III, in 1771; after the end of his active military career in 1776 he became a British agent in Spain. His Letters are “notable for [their] defence of sexual equality” (ODNB), which Jardine based on the profitable intermingling of the sexes which he observed on his travels: Jardine was a friend of William Godwin’s and his book was read by Mary Wollstonecraft, who reviewed it favorably in the fourth volume of the Analytical in 1789 (O’Neill, The Burke-Wollstonecraft Debate, p. 116). It proved a demonstrable influence on her Vindication of the Rights of Women, which was published in 1792 (Chernock, Men and the Making of Modern British Feminism, p. 21) A very good copy.

CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME.

LETTERS FROM SPAIN, TO FRIENDS IN ENGLAND.

LETTER I. On entering Spain from France. The Coun∣try. The Mountains. National and Provincial Objects. French Government.

LETTER II. Guipuscoa. Lime. Police. People. Women. Frontier. Industry. Liberty. Policy. Pasage. St. Sebastian’s.

LETTER III. Romantic Ruins and Situations. Strangers attached to Spain. Society of Arts. Good Conde. Industry.

LETTER IV. Iron. Trades. Music. Timber. Bilbao. Wool. Clergy. Commerce. Bourbons. Smuggling. The Poor. Mr. Bowles. Roads.

LETTER V. Mountains. Cannon. St. Ander. Ships. Foundery. Military. Asturias. Liberty with Security. Monopolies. Govern∣ment.

LETTER VI. Rivadeo. Winds. Provincial Characters and Distinctions. Galicia. Government. Marine.

LETTER VII. Of Travel and French Opinions. Spanish Dependence and Decline. Reflections. Dr. R—. Truth. Books.

LETTER VIII. Bowles. Manufactories. Pontz. History. Letters. Campomanes. Knowledge, and useful Arts.

LETTER IX. Talents. Conversation. Trades. Improve∣ments. Princes.

LETTER X. Government and Character of the French and Spaniards.

LETTER XI. Travellers. Galicia. Lands. Taxes. Law. Women.

LETTER XII. Chimneys. Windows. Trees. Theft. Religion.

LETTER XIII. Reflections on Home, on Finance, &c.

LETTER XIV. Andalusia. Cadiz. Trade to the Colonies. Laws of Ports.

LETTER XV. Virtue, public and private. Reformers. Abuses. Mysteries. Government.

LETTER XVI. General Knowledge. Universities. Arts. Travel. Military.

LETTER XVII. Theory with Practice. Public Diversions. Women. Theatre. Letters. Learning.

LETTER XVIII. Wit. Manners. Character. Taste. Language. Authors.

LETTER XIX. Sierra Morena. Olavide. Cordova. The Moors, their Arts, Manners, Taste. Walks. Society. Cortejos. Situation.

LETTER XX. Nobility. Mirth and Happiness. Antiqui∣ties. Arts and Population.

LETTER XXI. Country. Seguidillas. Timber. Sheep. Corporations. Nitre. Military Schools. Aranjuez.

LETTER XXII. Madrid. Arts. People. Escurial. Old Castile. Flocks. Towns. Church. Corn. Water. Government.

LETTER XXIII. Examples. Colonies and Companies. East Indies.

LETTER XXIV. Spanish Improvements. Roads. Canals. People. Laws. Languor.

LETTER XXV. Tolls. Mountains. Mauragatos. Galicia. St. Jago. Societies. Commerce.

LETTER XXVI. The Peninsula of Spain, and its Inhabitants.

LETTER XXVII. On Government.

LETTER XXVIII. Spanish ancient Government. Decline. Cha∣racter. Peculiarities. Edicts, and want of Confidence.

LETTER XXIX. Spanish Manners. Taste. Passions. Hap∣piness. Female Character. Ministry. Princes.

LETTER XXX. Situation. Trade. Prohibitions and high Duties.

LETTER XXXI. Commerce. Policy. War. Gibraltar. Family Compact. Mediterranean.

LETTER XXXII. Spanish Charity and Poor. Spirit of Power, of Control, and of Government.

LETTER XXXIII. Of Changes. Towns. Police. Of Princes.

LETTER XXXIV. Rural Taste and Improvements. Servants. Population. Money, &c. Impediments to the Rise of Spain.

LETTER XXXV. Military and Geographical Observations. Conclusion.

LETTERS FROM PORTUGAL, TO FRIENDS IN ENGLAND.

LETTER I. Galicia, and North of Portugal. Vigo. Spanish Councils. Defensive War. Industry, Taste, Science of the Portuguese. Water Finders. Frontier Coast.

LETTER II. Form, &c. of Portugal. Vegetable and animal Life. Character. Count la Lippe.

LETTER III. Policy. Industry. Character. Law.

LETTER IV. Manners and Education. Inquisitorial and Monastic Spirit. Toleration. Romish Church, &c.

LETTER V. Appearance of the Country. People. Braga. Oporto. Brazils. Wine Trade. Lower Classes.

LETTER VI. Lisbon. Marquis de Pombal. Sovereigns and Government. Character, &c.

LETTER VII. Of Books. Of Man. Portugal. Of Societies. The World. Europe. Confe∣deracies. Letters. War. Travelling, &c. in a variety of miscellaneous Re∣flections.

A LETTER FROM JERSEY. To A. J.

Barbaria by Jan Janssonius, shows the coast of North Africa, an area known in the 17th century as Barbaria, c. 1650

The Barbary pirates, Barbary corsairs, or Ottoman corsairs were mainly Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from the Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barbary Coast, in reference to the Berbers. The main purpose of their attacks was to capture slaves for the Barbary slave trade. Slaves in Barbary could be of many ethnicities, and of many different religions, such as Christian, Jewish, or Muslim. Their predation extended throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa’s Atlantic seaboard and into the North Atlantic as far north as Iceland, but they primarily operated in the western Mediterranean. In addition to seizing merchant ships, they engaged in razzias, raids on European coastal towns and villages, mainly in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal, but also in the British Isles, the Netherlands, and Iceland.

An action between an English ship and vessels of the Barbary Corsairs

While such raids began after the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the 710s, the terms “Barbary pirates” and “Barbary corsairs” are normally applied to the raiders active from the 16th century onwards, when the frequency and range of the slavers’ attacks increased. In that period, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli came under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire, either as directly administered provinces or as autonomous dependencies known as the Barbary states. Similar raids were undertaken from Salé and other ports in Morocco.

A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsairs by Laureys a Castro, c. 1681

Background: The Barbary corsairs were pirates and privateers who operated out of North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Tunis, Tripoli, and Algiers. This area was known in Europe as the Barbary Coast, in reference to the Berbers. Their predation extended throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa’s Atlantic seaboard and even to the eastern coast of South America with Brazil, and into the North Atlantic Ocean as far north as Iceland, but they primarily operated in the western Mediterranean. In addition to seizing ships, they engaged in raids on European coastal towns and villages, mainly in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal, but also in England, Scotland, the Netherlands, Ireland, and as far away as Iceland. The main purpose of their attacks was to capture Europeans for the slave market in North Africa.

The Barbary states were nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, but in practice they were independent and the Ottoman government in Constantinople was not involved.

Attacks:Since the 1600s, the Barbary pirates had attacked British shipping along the North Coast of Africa, holding captives for ransom or enslaving them. Ransoms were generally raised by families and local church groups. The British became familiar with captivity narratives written by Barbary pirates’ prisoners and slaves. During the American Revolutionary War, the pirates attacked American ships. On December 20, 1777, Morocco’s sultan Mohammed III declared that merchant ships of the new American nation would be under the protection of the sultanate and could thus enjoy safe passage into the Mediterranean and along the coast. The Moroccan-American Treaty of Friendship stands as America’s oldest unbroken friendship treaty with a foreign power. In 1787, Morocco became one of the first nations to recognize the United States of America. Starting in the 1780s, realizing that American vessels were no longer under the protection of the British navy, the Barbary pirates had started seizing American ships in the Mediterranean. As the U.S. had disbanded its Continental Navy and had no seagoing military force, its government agreed in 1786 to pay tribute to stop the attacks. On March 20, 1794, at the urging of President George Washington, Congress voted to authorize the building of six heavy frigates and establish the United States Navy, in order to stop these attacks and demands for more and more money. The United States had signed treaties with all of the Barbary states after its independence was recognized between 1786 and 1794 to pay tribute in exchange for leaving American merchantmen alone, and by 1797, the United States had paid out $1.25 million or a fifth of the government’s annual budget then in tribute. These demands for tribute had imposed a heavy financial drain and by 1799 the U.S. was in arrears of $140,000 to Algiers and some $150,000 to Tripoli. Many Americans resented these payments, arguing that the money would be better spent on a navy that would protect American ships from the attacks of the Barbary pirates, and in the 1800 Presidential Election, Thomas Jefferson won against incumbent second President John Adams, in part by noting that the United States was “subjected to the spoliations of foreign cruisers” and was humiliated by paying “an enormous tribute to the petty tyrant of Algiers”.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend