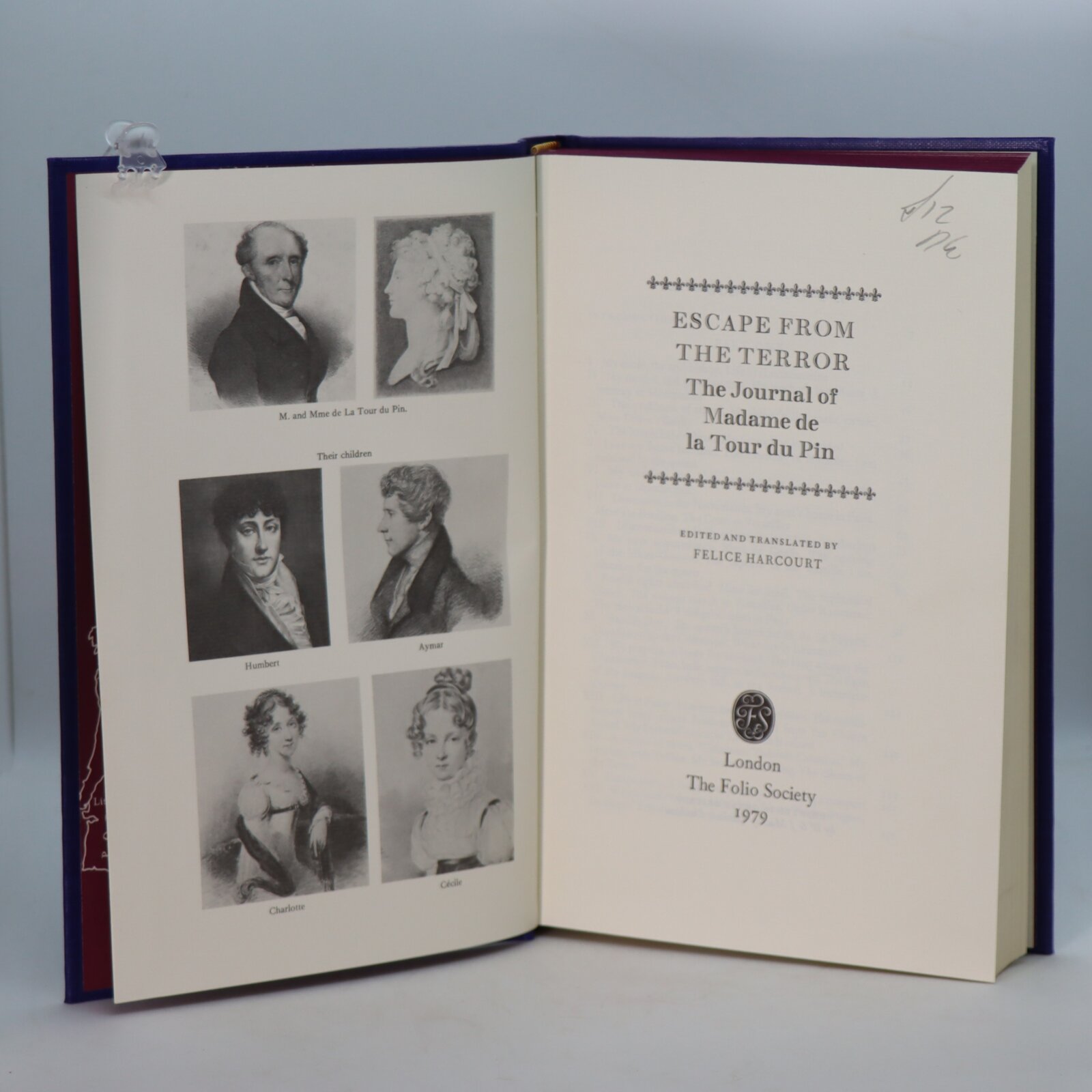

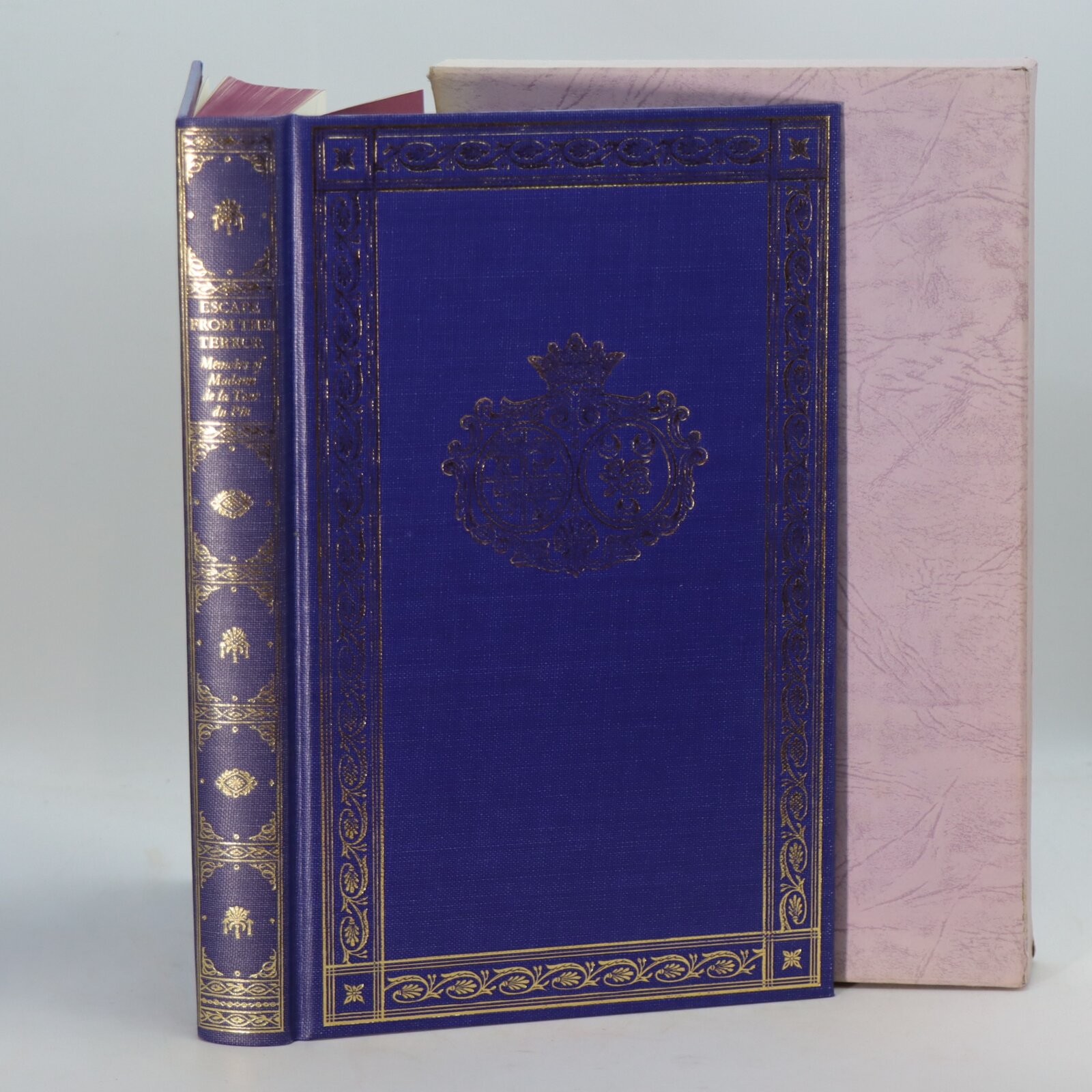

Escape from the Terror. Memoirs of Madame de la Tour du Pin.

By Felice Harcourt

Printed: 1979

Publisher: Folio Society. London

| Dimensions | 17 × 26 × 3.5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 17 x 26 x 3.5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

in a fitted box. Blue cloth with gilt edging and emblem decoration on front board. Gilt title and decoration on the spine.

It is the intent of F.B.A. to provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this book offered so to almost stimulate your feel and touch on the book. If requested, more traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Henriette-Lucy, Marquise de La Tour-du-Pin-Gouvernet (25 February 1770, Paris – 2 April 1853, Pisa) (also known as Lucie) was a French aristocrat famous for her posthumously published memoirs entitled Journal d’une femme de 50 ans. The memoirs are a first-hand account of her life through the Ancien Régime, the French Revolution, and the Imperial court of Napoleon, ending in March 1815 with Napoleon’s return from exile on Elba. Her memoirs serve as unique testimony to much unchronicled history.

She was present at Versailles during the assembly of the Estates General of 1789 and witnessed the Women’s March on Versailles at the outbreak of the French revolution. She also witnessed the peasant uprising called the Great Fear in the countryside.

Between October 1791 and March 1792, her husband served as ambassador to the Dutch Republic in The Hague, where she joined him, returning to France only in December 1792.

During the Reign of Terror of Robespierre in 1793, many of her friends and family were executed, and she fled Paris for the family estate of Le Bouilh in the Gironde region. During the summer of that year, their estate was seized by the government, and her father-in-law was imprisoned, and her husband went in hiding separate from her. With the help of Thérésa Tallien, she managed to secure a passport for herself and her husband from Jean-Lambert Tallien, a prominent member of the revolutionary French National Convention.

Directly after having secured their passports in 1794, she and her husband passed into exile for a new life on a dairy farm near Albany in Upstate New York. Although they were never officially listed as émigrés, Frédéric had been living in hiding prior to departure. She regarded this time as the happiest of her life. She vividly described the reality of owning slaves and interactions with the local Dutch families and the few remaining Native Americans of the area.

She was close to Talleyrand during his exile in the United States, and she returned to France as he did after the establishment of the Directorate in 1796. The couple left the United States because her husband wanted to resume his career in public life and shore up the family fortunes.

After the French Coup of 1799, which brought Napoleon to power, her husband was able to resume his diplomatic career. She was able to promote his career under Napoleon, who was looking for aristocrats to lend legitimacy to his power and, from 1804, his court. Her memoirs described an insider’s view of many events from the Imperial court of Napoleon.

She continued to follow her husband to his various diplomatic appointments after the Bourbon Restoration. They went into effective exile again after their son Aymar became involved in the anti-Orléanist plot of Caroline Ferdinande Louise, duchesse de Berry, in 1831, in the Vendée. Aymar escaped France but was condemned to death in his absence. The family sold its possessions in France soon after.

Following her husband’s death in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1837, she moved to Italy, where she died in Pisa.

The Reign of Terror, commonly called The Terror (French: la Terreur), was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to revolutionary fervour, anticlerical sentiment, and accusations of treason by the Committee of Public Safety.

There is disagreement among historians over when exactly “the Terror” began. Some consider it to have begun only in 1793, giving the date as either 5 September, June or March, when the Revolutionary Tribunal came into existence. Others, however, cite the earlier time of the September Massacres in 1792, or even July 1789, when the first killing of the revolution occurred.

The term “Terror” being used to describe the period was introduced by the Thermidorian Reaction who took power after the fall of Maximilien Robespierre in July 1794, to discredit Robespierre and justify their actions. Today there is consensus amongst historians that the exceptional revolutionary measures continued after the death of Robespierre, and this subsequent period is now called the “White Terror”. By then, 16,594 official death sentences had been dispensed throughout France since June 1793, of which 2,639 were in Paris alone; and an additional 10,000 died in prison, without trial, or under both of these circumstances.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend