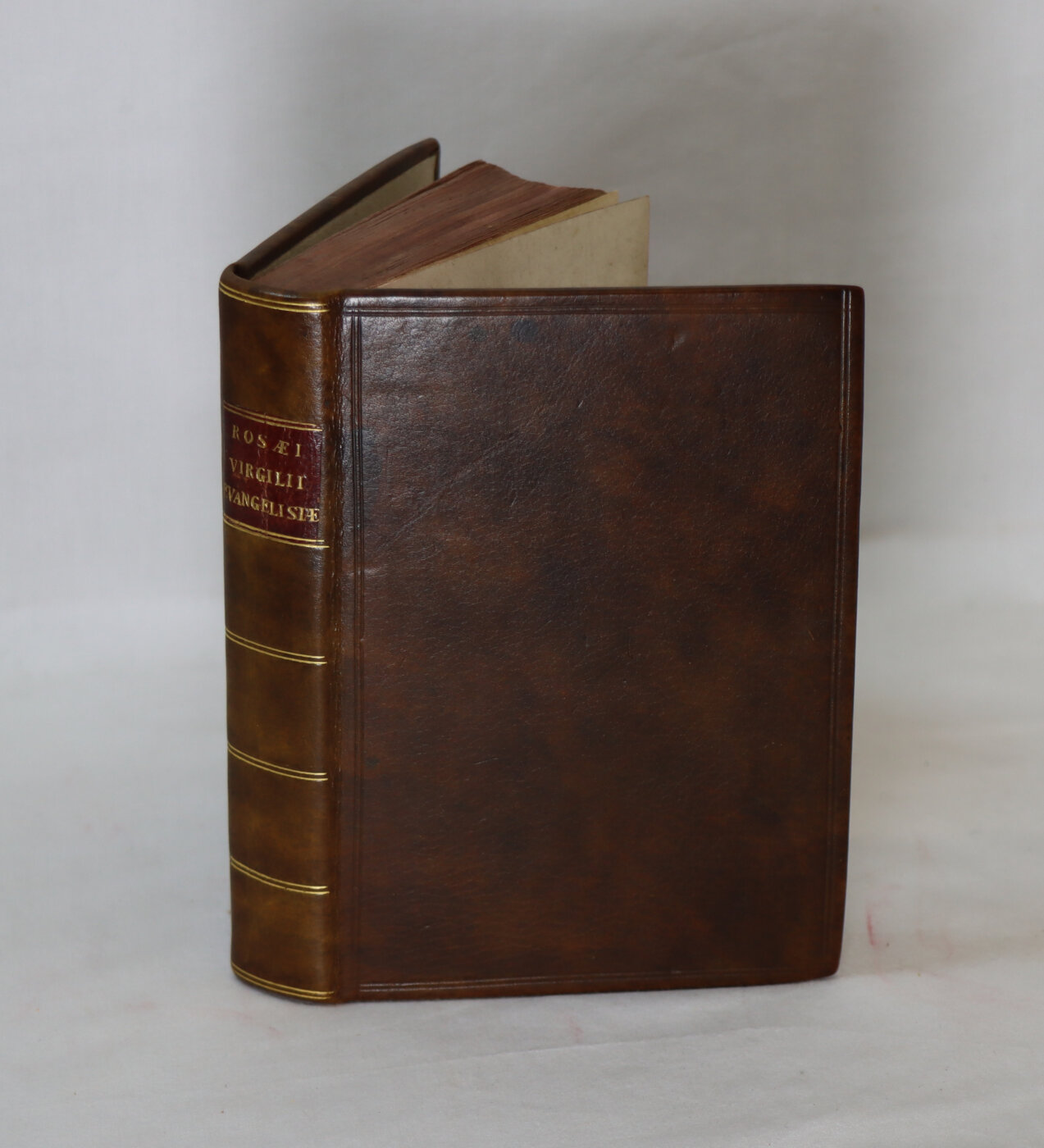

Virgil II Evangelisantis.

By Alexandro Rosaeo Aberdonese

Printed: 1638

Publisher: William Marshall. London

| Dimensions | 11 × 15 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: Latin

Size (cminches): 11 x 15 x 3

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Item information

Description

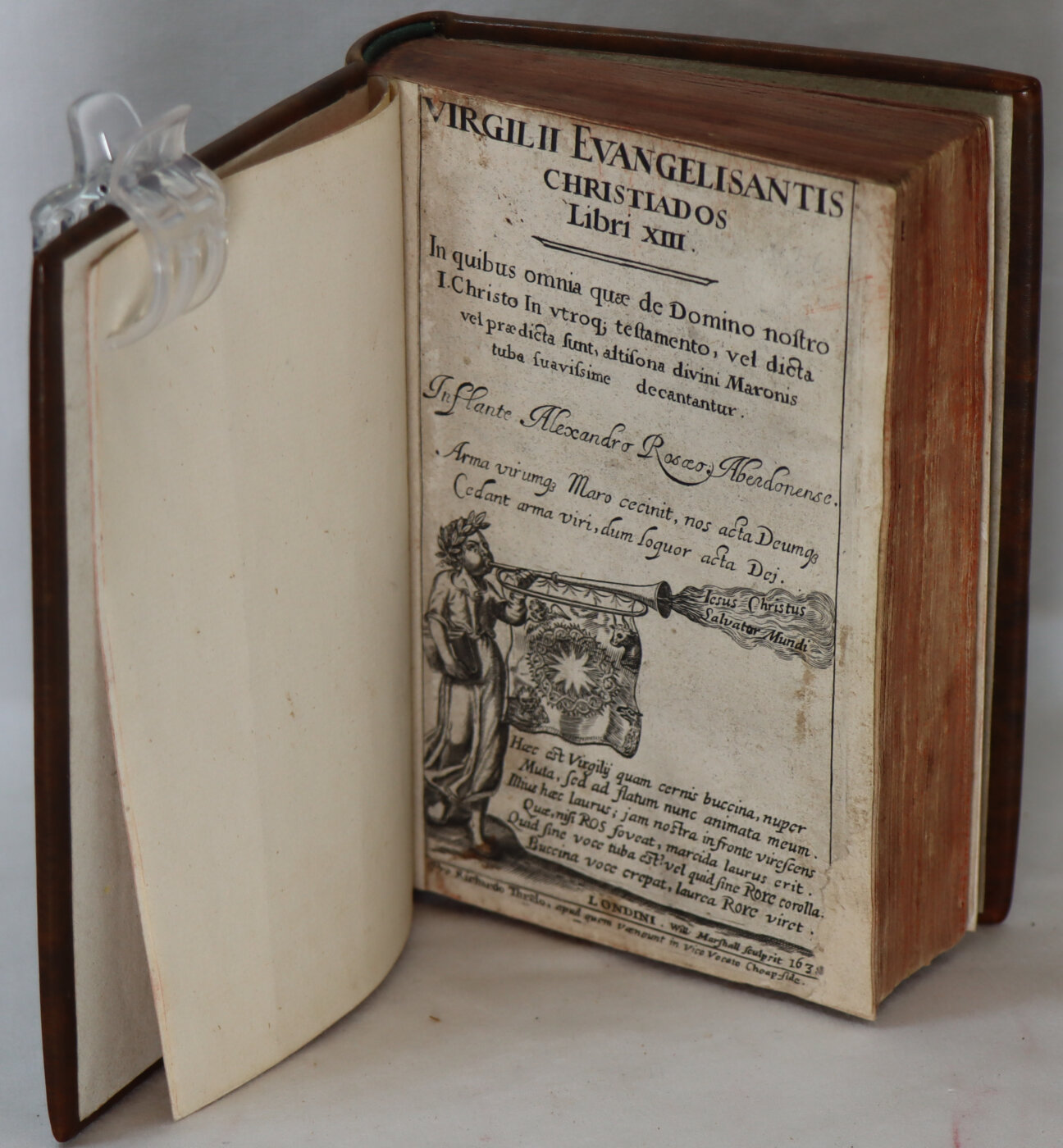

Dark brown calf binding with maroon title plate, gilt banding and title on the spine.

-

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

-

Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

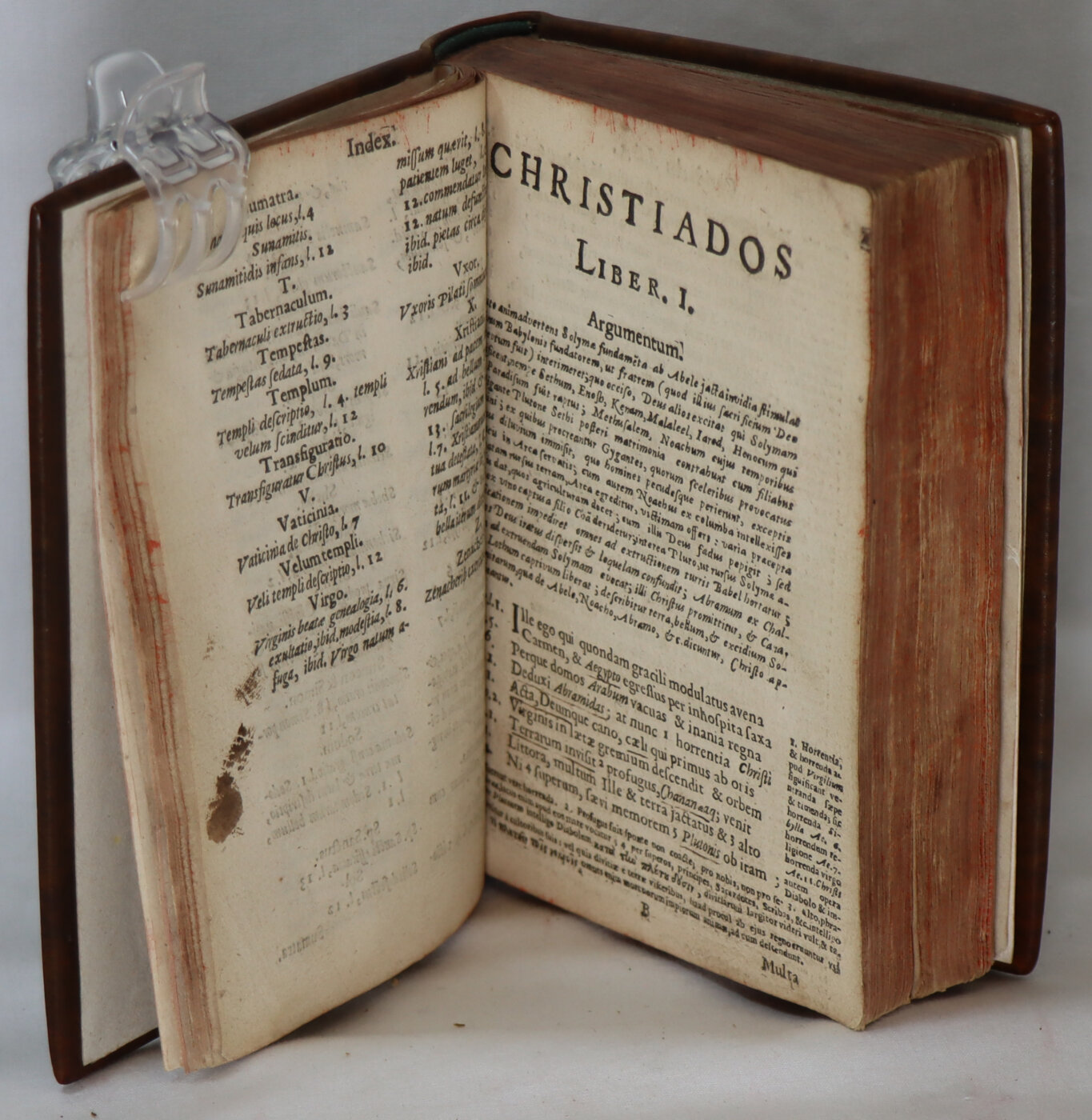

Virgilii Evangelisantis Christiados Libri xiii (1634), a cento composed entirely from Virgil

‘A cento is a poetical work wholly composed of verses or passages taken from other authors, especially the Greek poet Homer and the Roman poet Virgil, disposed in a new form or order’

See the photographs of this beautiful, very rare, and important book by Alexander Ross (c. 1590–1654) who was a prolific Scottish writer and controversialist. He was Chaplain-in-Ordinary to Charles I). Rebound in the 18th century and refurbished in the 20th century. Dedicated to Charles I of England. Emblematic engraved title by William Marshal depicting Virgil as wingless angel, wearing wreath on head, playing trumpet from which hangs banner with crown of thorns encircling sun and surrounded by beasts of the Evangelists and out of which issue the words “Iesus Christus Salvator Mundi.” This long declamation in verse, composed of passages from different authors was disposed in a new order (according to the poetic form known as “cento”), and extols the insights pre-Christian Virgil.

Alexander Ross was born in Aberdeen but spent much of his later life in England, as vicar on the Isle of Wight from 1634 to his death twenty years later. He was a prolific and established writer, and is best known for his first English translation of the Koran (from the French). While living in Southampton, Ross produced two Virgilian centos made up of lines from the works of Virgil, who was for Ross the “King of Poets.” The first, the Virgilius Evangelisans, uses Virgil’s words to relate the Christian Gospel. In 1637, Ross worked this concept out on a more impressive scale as the Virgilii Evangelisantis Christiados (The “Christiad” of the Evangelist Virgil). His epic work consisted of more than ten thousand Virgilian hexameters which traced the “types” of Christ in the Old Testament and examined His role and prophecies in Scripture, with each cento giving the principal Biblical events from the death of Abel to the Ascension of Christ. The Virgilii Evangelisantis Christiados is rich in allusions to England’s growing unrest and concludes with an appeal for peace and unity among Christians. The book is known for the variances in its makeup, notably in the final leaves. Very rare and important.

Eclogue 4, also known as the Fourth Eclogue, is the name of a Latin poem by the Roman poet Virgil. Part of his first major work, the Eclogues, the piece was written around 40 BC, during a time of brief stability following the Treaty of Brundisium; it was later published in and around the years 39–38 BC. The work describes the birth of a boy, a supposed savior, who once of age will become divine and eventually rule over the world. During late antiquity and the Middle Ages, a desire emerged to view Virgil as a virtuous pagan, and as such the early Christian theologian Lactantius, and St. Augustine—to varying degrees—reinterpreted the poem to be about the birth of Jesus Christ.

This belief persisted into the Medieval era, with many scholars arguing that Virgil not only prophesied Christ prior to his birth but also that he was a pre-Christian prophet. Dante Alighieri included Virgil as a main character in his Divine Comedy, and Michelangelo included the Cumaean Sibyl on the ceiling painting of the Sistine Chapel (a reference to the widespread belief that the Sibyl herself prophesied the birth of Christ, and Virgil used her prophecies to craft his poem). Modern scholars, such as Robin Nisbet, tend to eschew this interpretation, arguing that seemingly Judeo-Christian elements of the poem can be explained through means other than divine prophecy.

By the turn of the 20th century, most scholars had abandoned the idea that the Fourth Eclogue was prophetic, although “there [were] still some to be found who”, in the words of Comparetti, “[took] this ancient farce seriously.” Robin Nisbet has argued that the supposed Christian nature of the poem is a by-product of Virgil’s creative references to disparate religious texts; Nisbet proposes that Virgil probably appropriated some elements used in the poem from Jewish mythology by means of Eastern oracles. In doing so, he adapted these ideas to Western (which is to say, Roman) modes of thought.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend