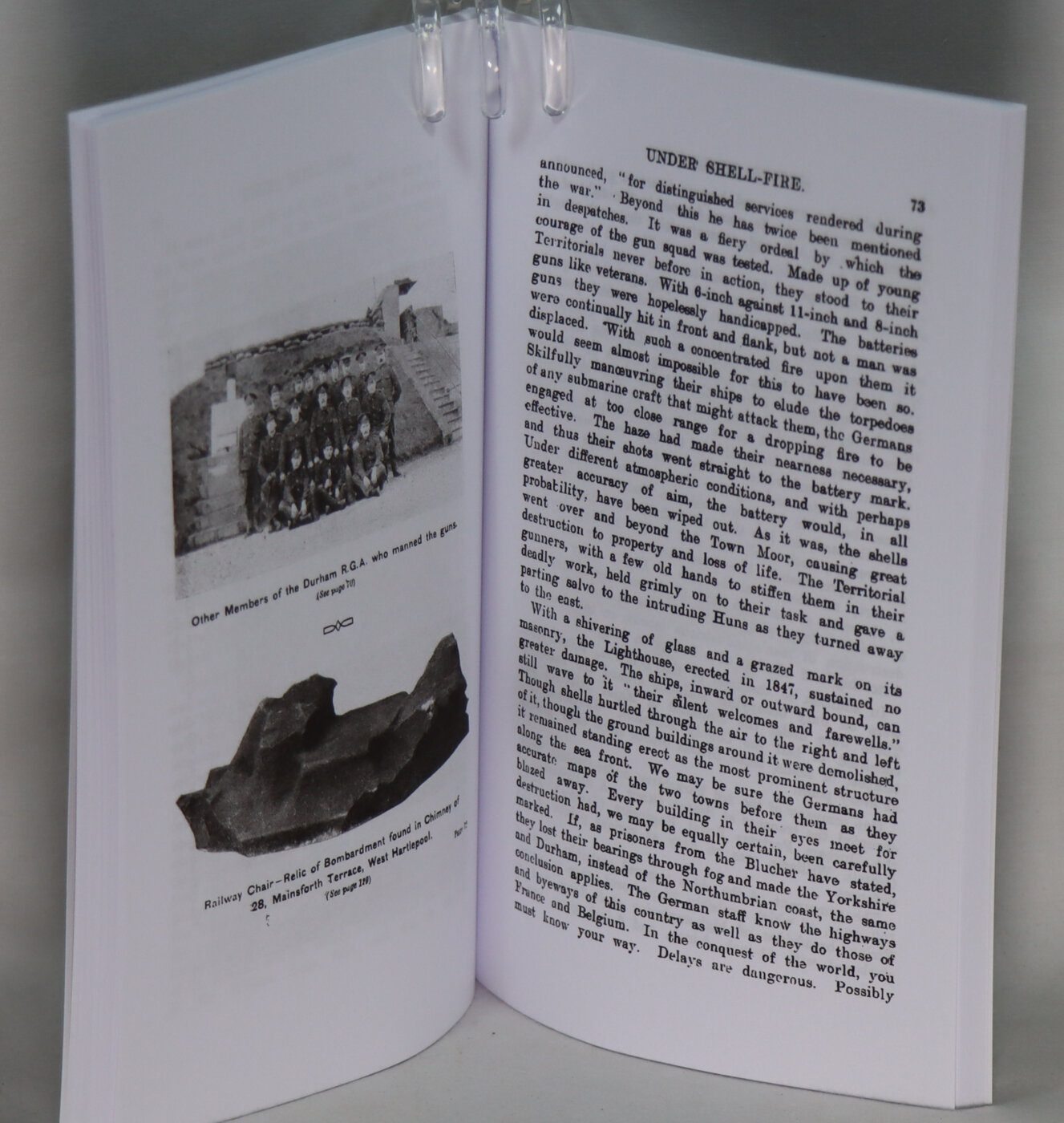

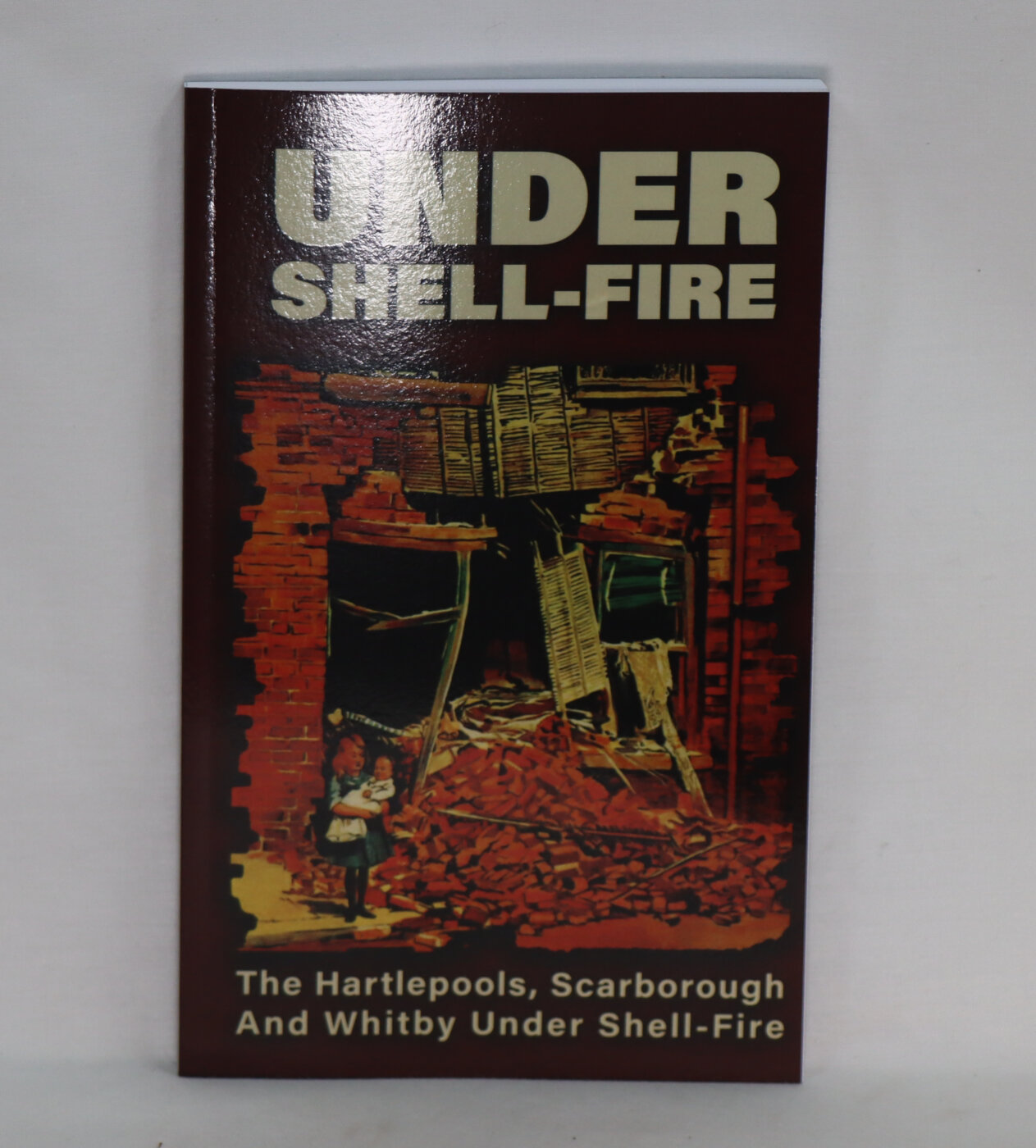

Under Shellfire.

Printed: Circa 2023

Publisher: The Naval & Military Press. East Sussex

| Dimensions | 13 × 20 × 1 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 13 x 20 x 1

Condition: As new (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Paperback. Brown board binding with white title and bomb damage image.

- We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

On Wednesday 16 December 1914, the inhabitants of Scarborough in North Yorkshire awoke to find a heavy mist hanging over their seaside town – and three German warships sailing rapidly towards them.

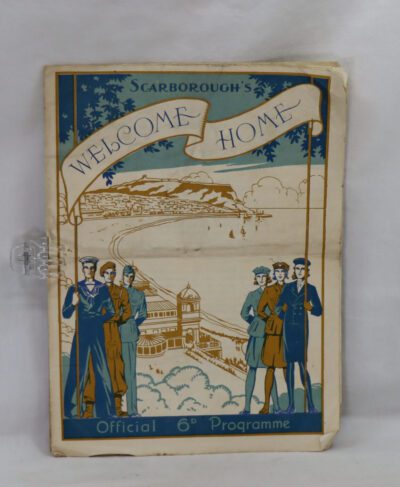

The devastating attack that followed on Scarborough, together with Hartlepool and Whitby, was the first time civilians had been targeted on English soil during the First World War. It so shocked the nation that ‘Remember Scarborough’ became a rallying cry for a huge recruitment campaign – War comes to Britain in December 1914

Early on the morning of the 16th December 1914, a squadron of German battlecruisers and light cruisers commanded by Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper, emerged out of the mist off the east coast of England to unleash a bombardment upon the towns of Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby. The attack was unprecedented, bringing war, fatally, to Britain’s shores for the first time since the Civil War. The elegant seaside spa town of Scarborough was undefended; Hartlepool, which had a clutch of civilian docks and factories, was defended by three six-inch naval guns on the seafront, manned by 11 officers and 155 local men of the Durham Royal Garrison Artillery. The guns fired upon the attackers, killing eight German sailors and wounding 12, but they were no match for the estimated 1150 or so shells that came hurtling and rattling through the buildings and streets of the towns.

The damage inflicted by the raid, which was to last until about 9:30am, was extensive. In Scarborough 18 civilians were reported to have been killed. Hartlepool suffered worse with 101 killed and hundreds more injured. With another four people killed during the 11 minute shelling of the fishing town of Whitby, the news that civilians had been attacked and killed on British soil sent shockwaves around the country. The fact that, inevitably, women and children, some in their beds, many on their way to school, had been victims of the attack caused widespread condemnation of the German fleet’s actions. This, clearly, was proof that the Allies were fighting a barbaric and unscrupulous enemy.

With public opinion sufficiently inflamed, the outrage was soon being used as a subject to stir recruitment. Lucy Kemp-Walsh’s famous ‘Remember Scarborough’ poster, showing a furious Britannia urging the young men of Britain to look out to sea and avenge the killings is perhaps the most memorable from this period. Another, in irate red letterpress declared, ‘The Germans who brag of their “CULTURE” have shown what it is made of by murdering defenseless women and children at Scarborough. But this only strengthens Great Britain’s resolve to crush the German barbarians.’

But it’s interesting to note the varied depictions of the event among the resources we have here at Mary Evans. We have a photograph from the collection of the silhouette artist H. L. Oakley showing Oakley’s famous ‘Think!’ recruitment poster in York railway station, alongside another more wordy poster preaching about the need to avenge the attacks on York’s nearby neighbours. The 26 December issue of The Sphere magazine, a publication that strove to faithfully depict events as they happened, featured an illustration by their special artist, Fortunino Matania drawn from a sketch made by another of the publication’s artists, G. H. Davis who was at Hartlepool and witnessed the scenes himself. It shows the Baptist Chapel, with a large part of its upper front smashed away. It accurately mirrors photographs of the damage to the chapel subsequently circulated, but also depicts the following incident, described in the accompanying caption:

‘A shell coming from the sea hit the Baptist Chapel, smashing in a large portion of the upper part of the building; it then went clean through the building, hurtling into the roadway, from which it rebounded and crashed through the first-floor bedroom of the house, seen on the extreme right, killing a woman. As the shell hit the chapel, causing a haze of dust, men and women came rushing down from all the houses around. One woman was struck down and fell forwards on the road; a Territorial who rushed to her assistance had his rifle blown out of his hand.’

The Tatler magazine featured, on their 23rd December cover, a photograph of a devastated house in Wykeham Street, Scarborough where a Mrs Barnett and two children were killed with the words, ‘Enemy’s shells damage undefended British towns for the first time in the history of our country’

Not everyone reflected the pathos and fiery rage of the now-famous recruiting posters. The Sketch instead showed the window of a Scarborough antiques dealer with a portrait of Lord Kitchener still defiantly hanging in the window, despite the damage done to the rest of the shop front. The Bystander displayed a cheeky sarcasm with a double-page spread picturing, ‘The Havoc Wrought on England’s Great East Coast Stronghold.’ Appealing to its sophisticated readership, it lampooned the German attack treating the enemy’s ‘frightfulness’ and unsporting brand of warfare with a contemptuous tongue in its cheek.

‘The lives of good and brave German soldiers and sailors have been avenged at the expense of English hotel-keepers, shopmen, clerks, artisans, women and children,’ it remarked acidly, continuing, ‘For the “Scharnhorst”, Germany exacted the price of Scarborough Grand Hotel; for the “Gneisenau” she has the grocer’s shop of Mr Merry Weather… By sheer inadvertence, it must be admitted, some shells fell at Hartlepool, which has since been discovered by the Germans to have forts and a dockyard. But these accidental lapses into fair warfare will occur even in the best regulated Navies.’

German satirists were at work too and in the humorous magazine, Lustige Blatter in January 1915, John Bull was pictured being hit in a somewhat sensitive area by the artist W. A. Wellner – proof perhaps that Germany had felt the attack entirely justified and comparatively successful.

Not to be outdone, in February 1915, The Tatler published a cartoon based on the famous ‘Skegness is so bracing’ poster by John Hassall. ‘With apologies to John Hassall’, J. H. Thorpe (who joined the Artists’ Rifles) gave his own homage to the iconic illustration, making a small adjustment whereby Hassall’s old salt was forced to hop around to avoid shells falling on the beach around him. It is one of many cartoons that show the characteristically self-deprecating British sense of humour; able to laugh at themselves even in the darkest of times. Whether such a cartoon would have been as popular to readers of more jingoistic daily papers such as the Morning Post or John Bull is debatable.

Our store of material documenting this devastating day 100 years ago looks at the event from all angles. We have maps and diagrams analysing the attack from magazines like The Sphere and Illustrated War News and even advertisements from the summer of 1914 promote the bracing air of Scarborough as the ideal holiday tonic. We have also recently added James Clark’s famous painting, ‘The Bombardment of the Hartlepools’ (top left picture at start of this post) to our collection from Hartlepool Art Gallery, while a commemorative booklet, ‘The Bombardment of Scarborough,’ has come to us via David Cohen Fine Art and includes many photographs and illustrations.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend