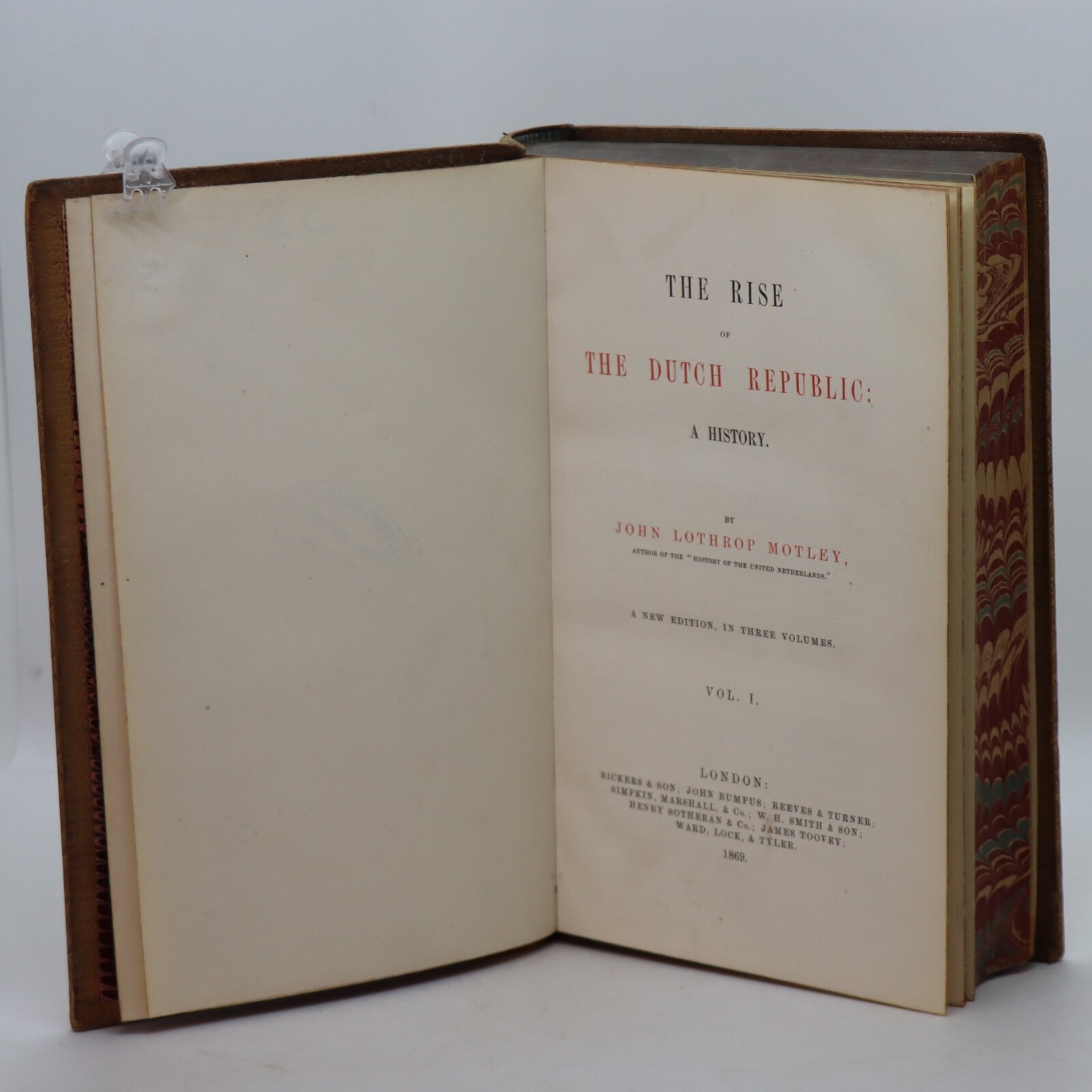

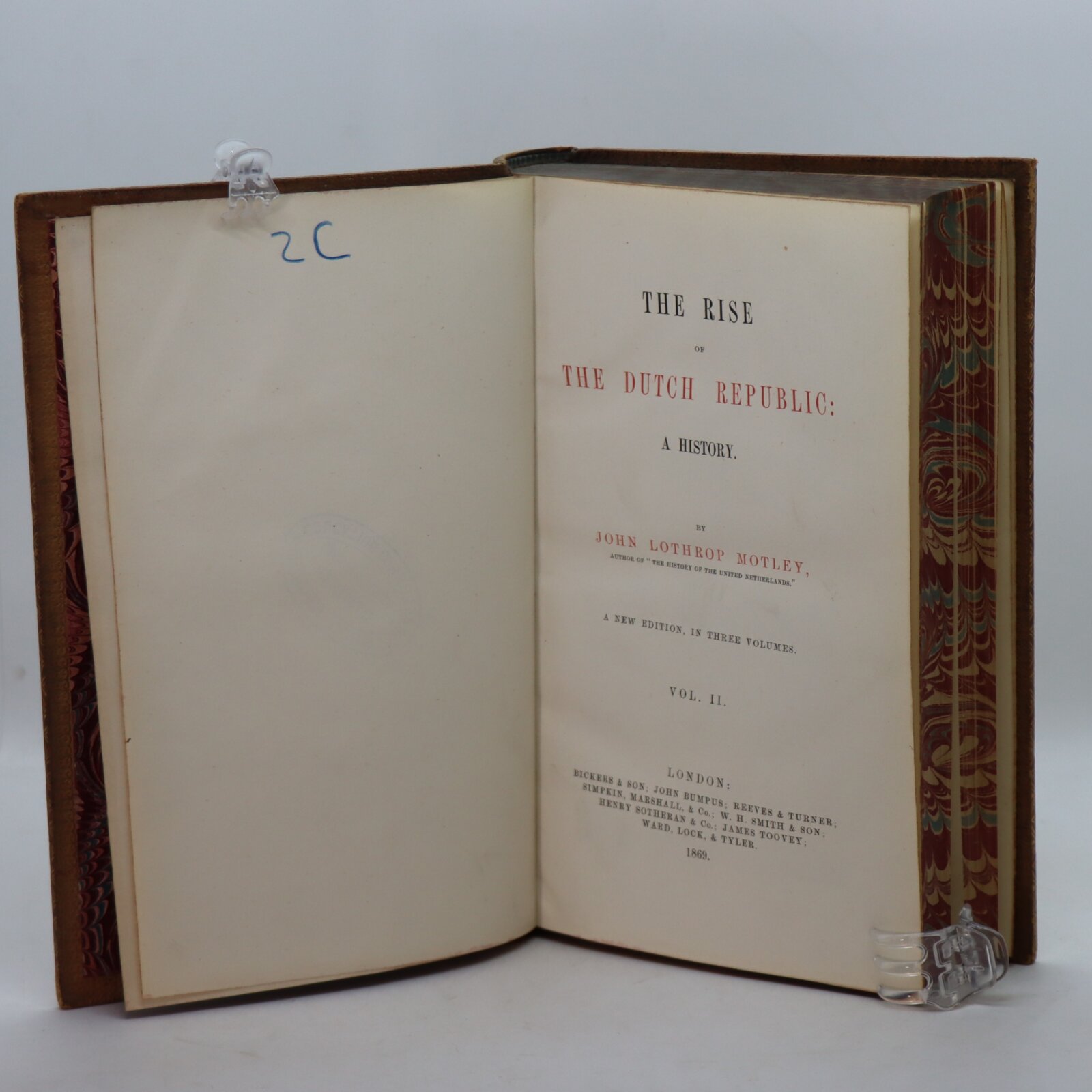

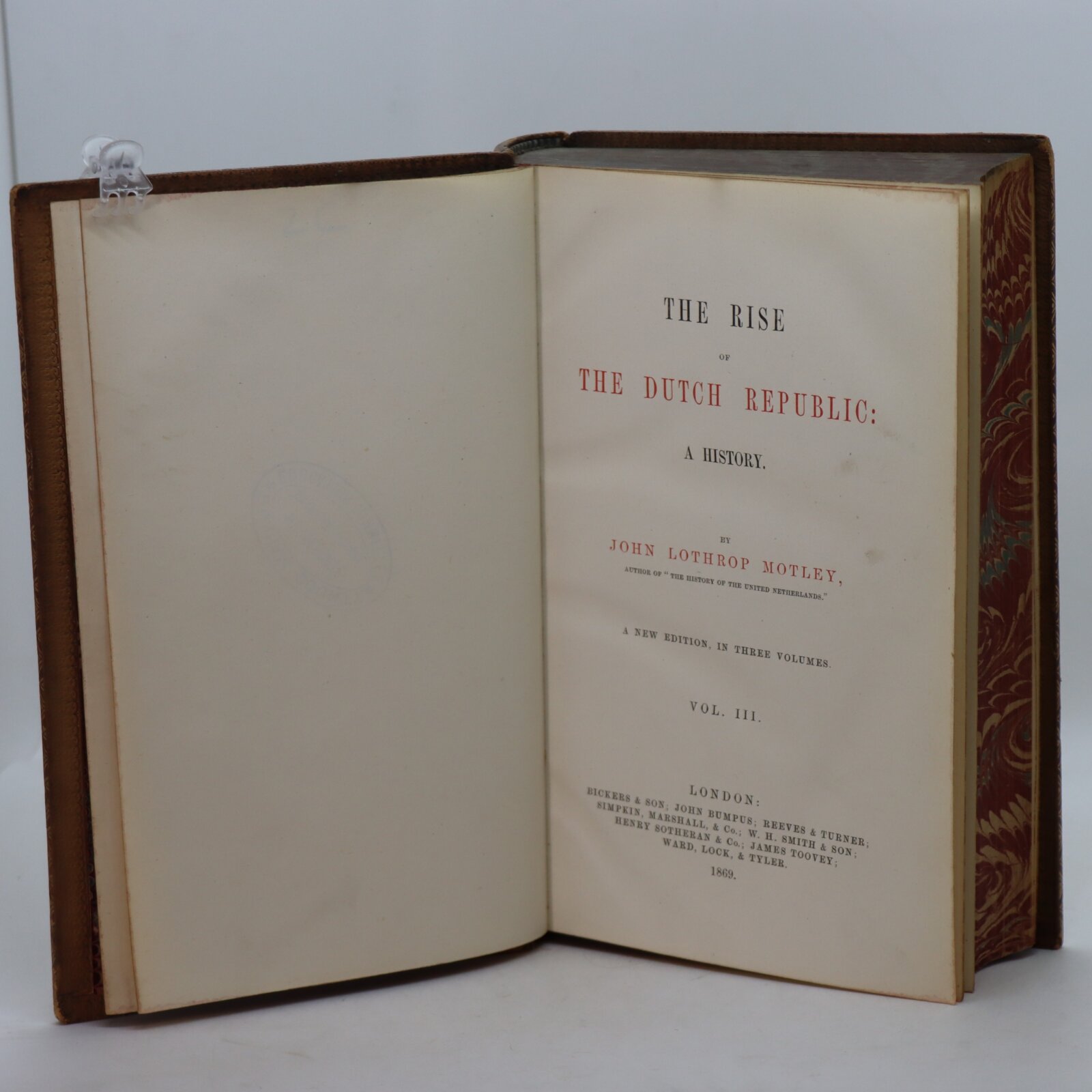

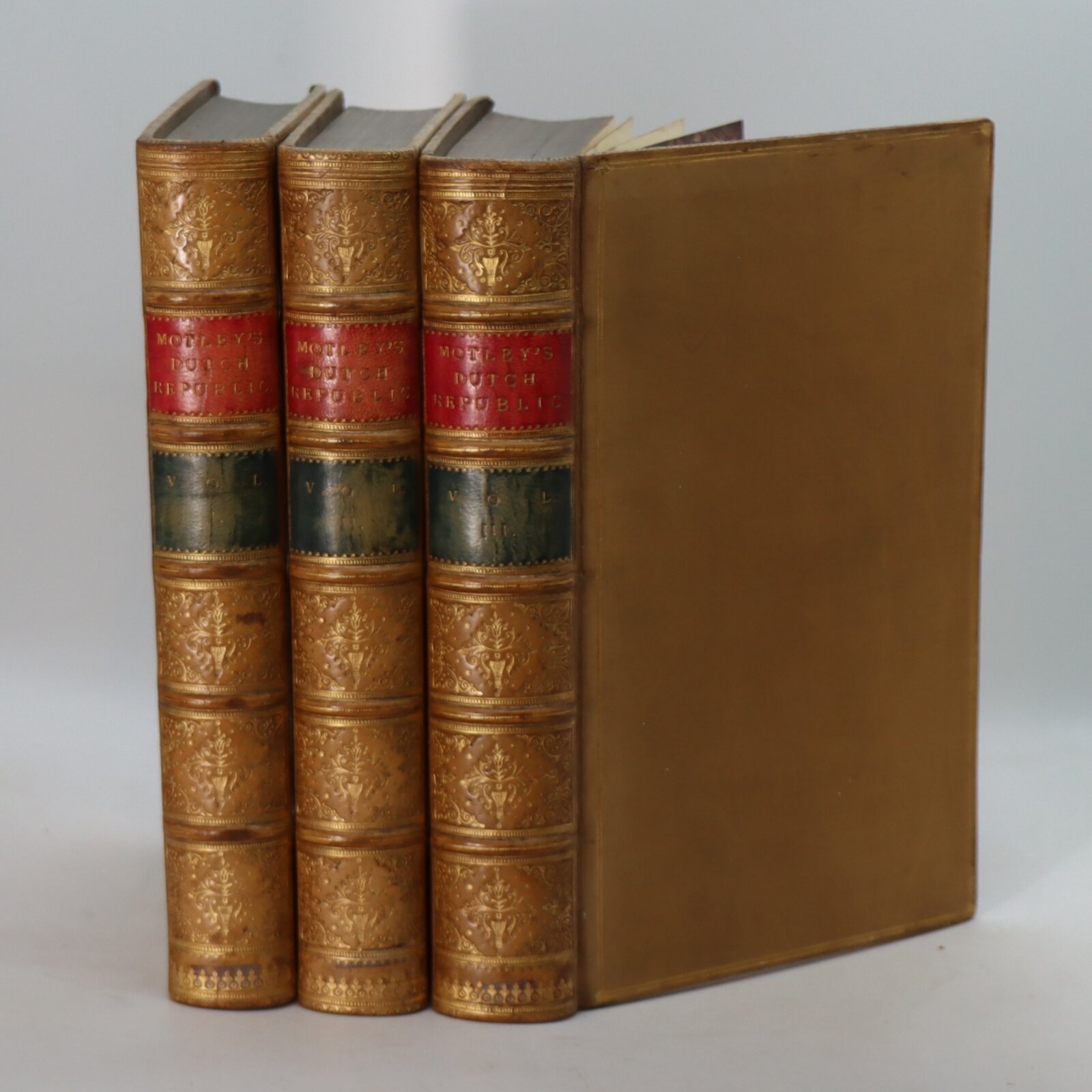

The Rise of the Dutch Republic. Volumes I, II & III. Motley.

By John Lothrop Motley

Printed: 1892

Publisher: Bickers & Son. London

Edition: New Edition in three volumes

| Dimensions | 16 × 23 × 4 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 16 x 23 x 4

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Your items

Item information

Description

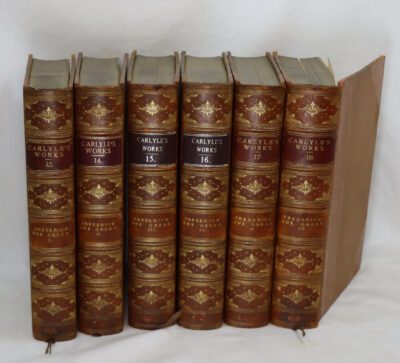

Volumes I, II, and III. Full tan calf with red and green title pates, gilt raised banding and gilt decoration. Dimensions are for one volume. Very fine binding by Bickers & Son, London

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feel and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

A new edition, very readable

A truly magnificent set

John Lothrop Motley (April 15, 1814 – May 29, 1877) was an American author and diplomat. As a popular historian, he is best known for his works on the Netherlands, the three volume work The Rise of the Dutch Republic and four volume History of the United Netherlands. As United States Minister to Austria in the service of the Abraham Lincoln administration, Motley helped to prevent European intervention on the side of the Confederates in the American Civil War. He later served as Minister to the United Kingdom (Court of St. James) during the Ulysses S. Grant administration.

In 1846, Motley had begun to plan a history of the Netherlands, in particular the period of the United Provinces, and he had already done a large amount of work on this subject when, finding the materials at his disposal in the United States inadequate, he went with his wife and children to Europe in 1851. The next five years were spent at Dresden, Brussels, and The Hague in investigation of the archives, which resulted in 1856 in the publication of The Rise of the Dutch Republic, which became very popular. It speedily passed through many editions and was translated into Dutch, French, German, and Russian. In 1860, Motley published the first two volumes of its continuation, The United Netherlands. This work was on a larger scale and embodied the results of a still greater amount of original research. It was brought down to the truce of 1609 by two additional volumes, published in 1867.

The books were popular and critical successes in both Britain and the United States, and multiple editions over the decades sold tens of thousands of copies. It was a favourite prize that schools awarded to their best students. Owen Edwards says of Motley, “He and he alone had created a Dutch awareness on a wide scale.”

American critics have given the book mixed reviews. It was quite popular in its day, but modern scholars argue:

Motley’s overdramatization and didacticism, combined with research less intense than Prescott’s or Parkman’s, have cost his works in staying power. Scholars have largely rewritten the story of the Dutch Republic; it is the rare modern who would, for pleasure alone, read Motley from cover to cover, even his Rise of the Dutch Republic. But particular characterizations and episodes in his writings–notably the portraits of William of Orange and Philip II and the descriptions of the Siege of Leyden, the abdication of Charles V, and the assassination of William– are not excelled in American literature for glint and lift and thud of language.

The reception of Motley’s work in the Netherlands itself was not wholly favourable, especially as Motley described the Dutch struggle for independence in a flattering light, which caused some to argue he was biased against their opponents. Although historians like the orthodox Protestant Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer (whom Motley extensively quotes in his work) viewed him very favourably, the eminent liberal Dutch historian Robert Fruin (who was inspired by Motley to do some of his own best work, and who had reported already in 1856 in The Westminster Review Motley’s edition on the Rise of the Dutch Republic) was critical of Motley’s tendency to make up “facts” if they made for a good story. Though he admired Motley’s gifts as an author, and stated that he continued to hold the work as a whole in high regard, he stressed it still required “addition and correction”.

The humanist historian Johannes van Vloten was very critical, and responded to Fruin in 1860: “I agree less with your too favourable judgement….We cannot build on Motley[‘s foundation]; for that—apart from the little he copied from Groen’s Archives and Gachard’s Correspondences—for that his views are generally too obsolete.” Although appreciating his efforts to make Dutch history known among an English-speaking audience, Van Vloten argues that Motley’s lack of knowledge of the Dutch language prevented him from sharing the latest insights of the Dutch historiographers, and made him vulnerable to bias in favour of Protestants and against Catholics.

Want to know more about this item?

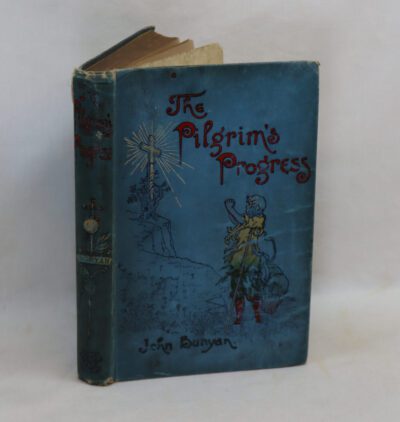

Related products

Share this Page with a friend