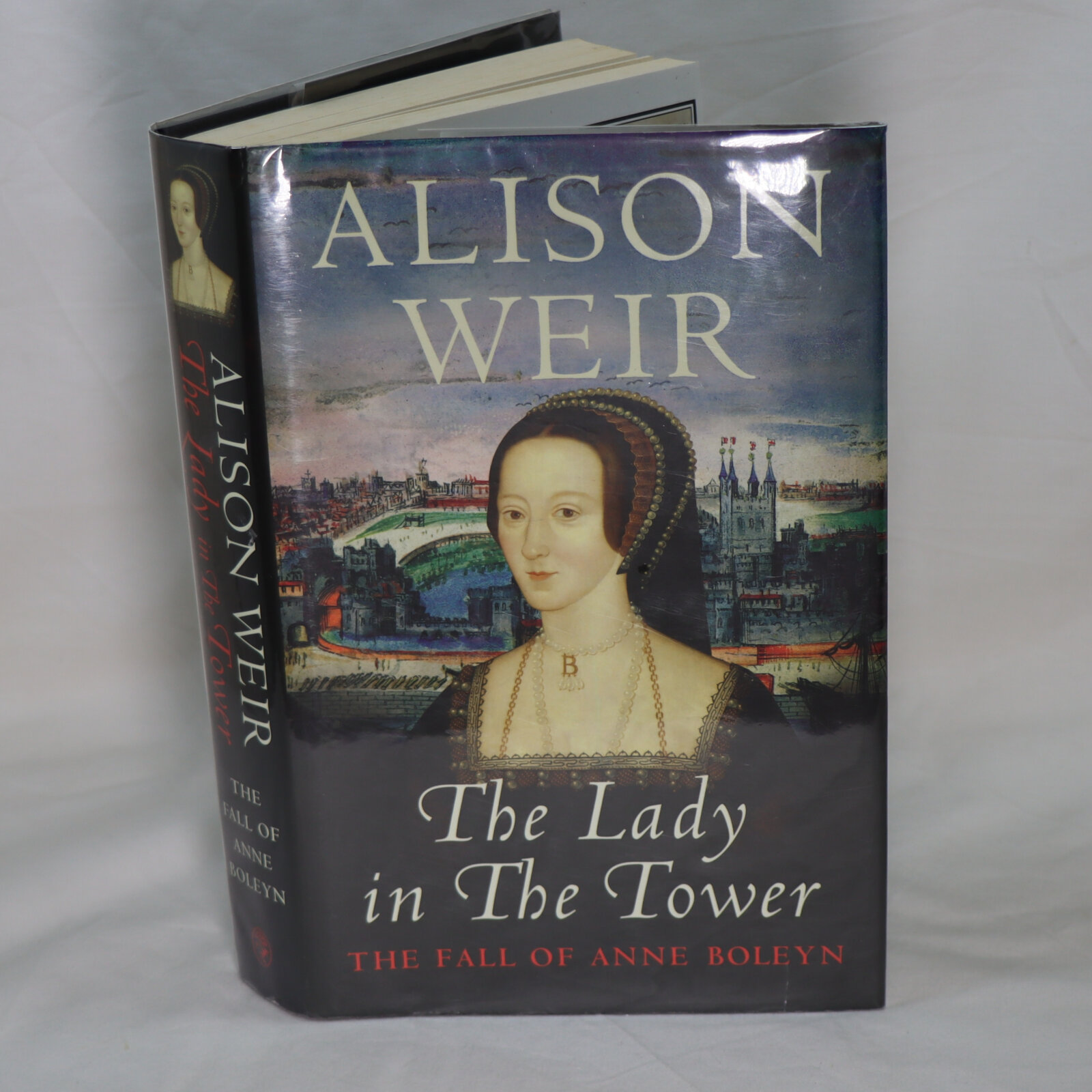

The Lady in the Tower.

By Alison Weir

ISBN: 9780712640176

Printed: 2009

Publisher: Jonathan Cape. London

| Dimensions | 17 × 24 × 4 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 17 x 24 x 4

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

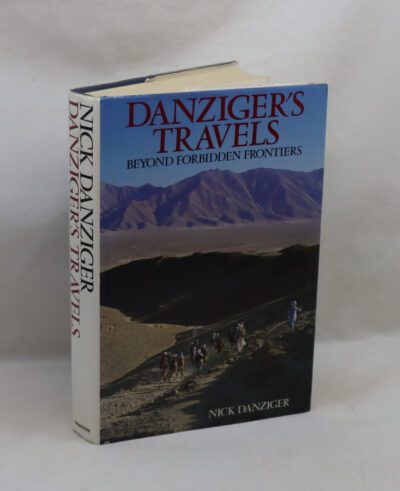

In the original dustsheet. Black cloth binding with gilt title on the spine.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

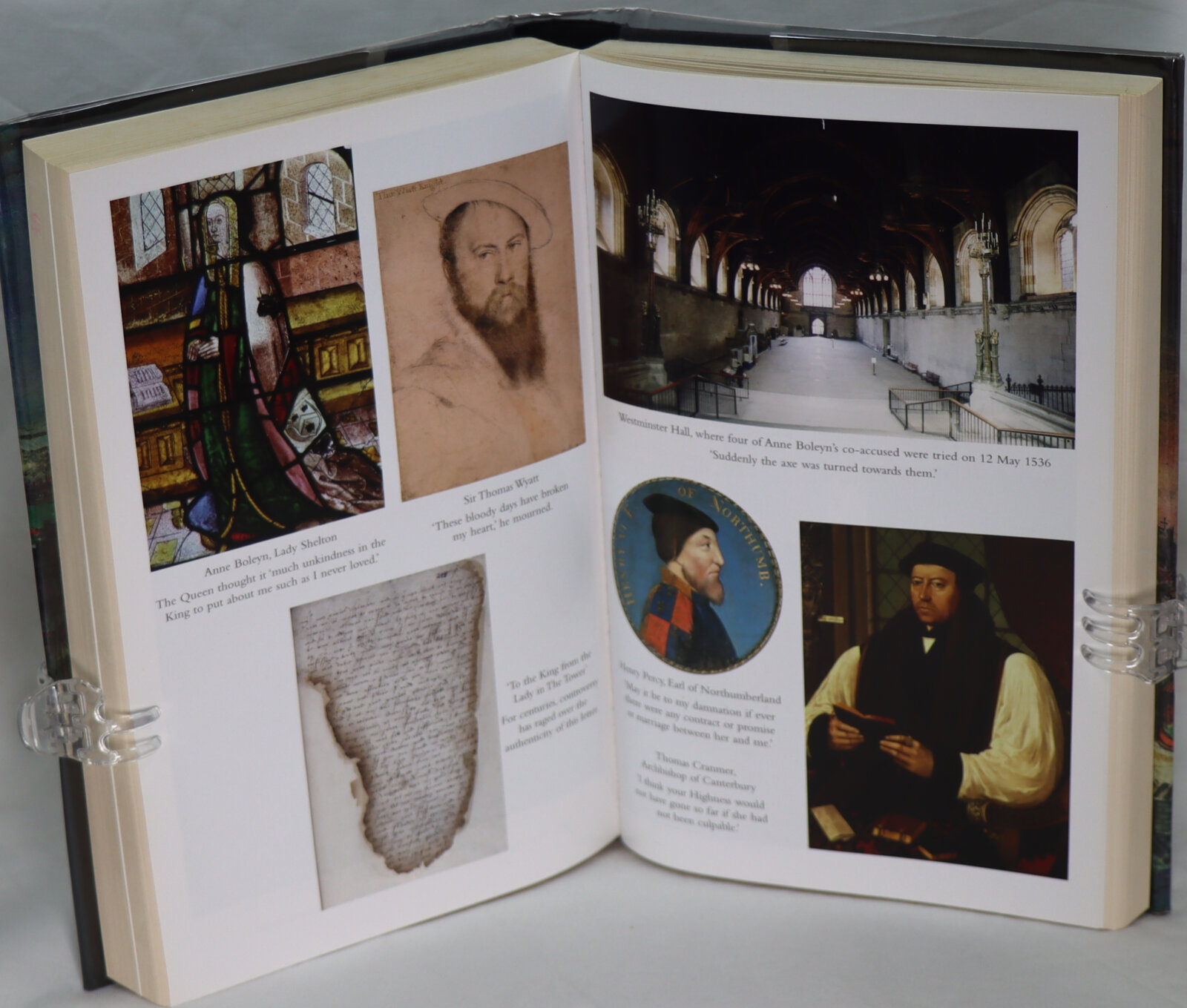

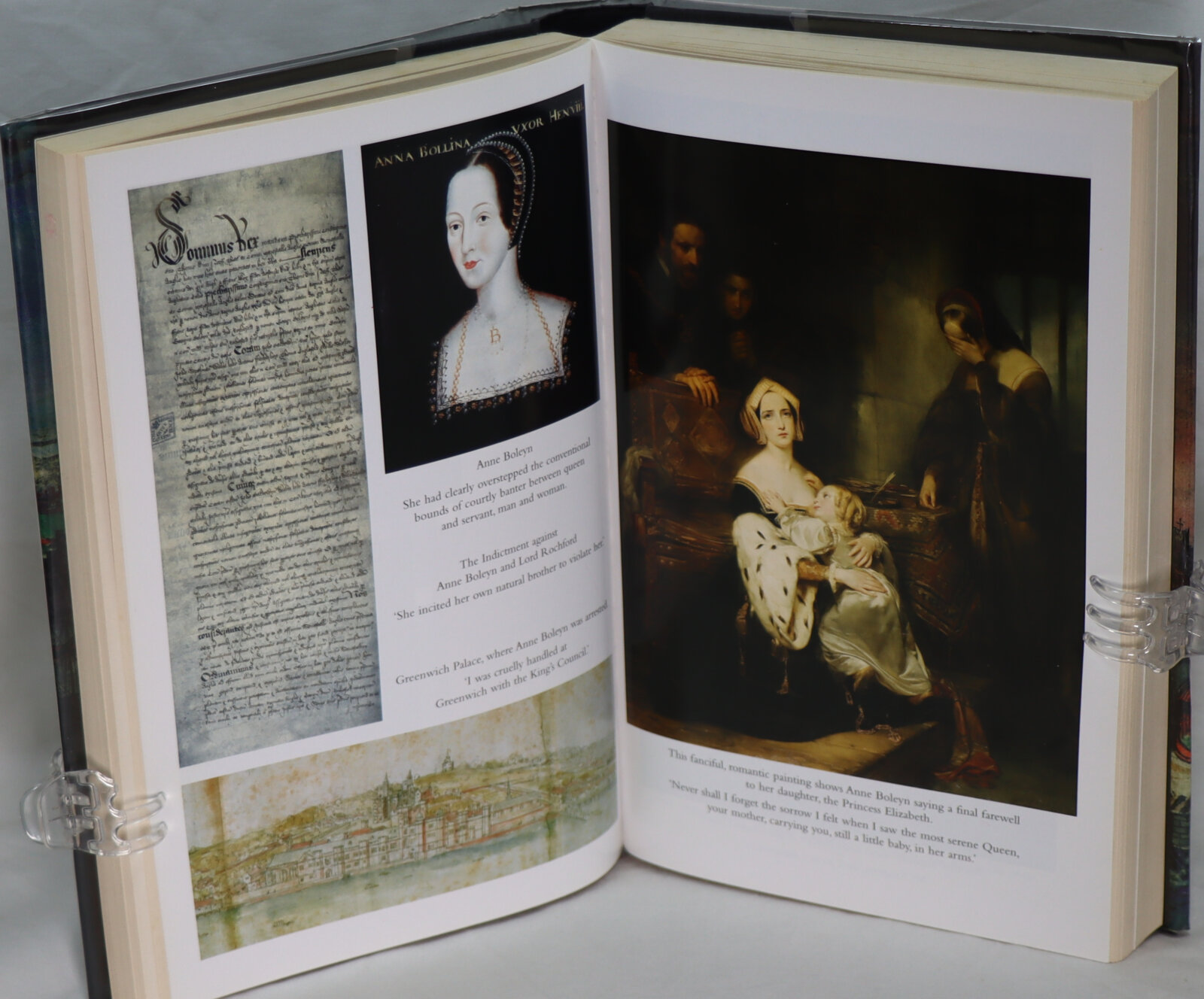

The imprisonment and execution of Queen Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s second wife, in May 1536 was unprecedented in the annals of English history. It was sensational in its day, and has exerted endless fascination over the minds of historians, novelists, dramatists, poets, artists and film-makers ever since. Anne was imprisoned in the Tower of London on 2 May 1536, and tried and found guilty of high treason on 15 May. Her supposed crimes included adultery with five men, one her own brother, and plotting the King’s death. She was executed on 19 May 1536. Mystery surrounds the circumstances leading up to her arrest. Was it Henry VIII who, estranged from Anne, instructed Master Secretary Thomas Cromwell to fabricate evidence to get rid of her so that he could marry Jane Seymour? Or did Cromwell, for reasons of his own, construct a case against Anne and her faction, and then present compelling evidence before the King? Following the coronation of her daughter Elizabeth I as queen, Anne was venerated as a martyr and heroine of the English Reformation. Over the centuries, Anne has inspired many artistic and cultural works and, as a result, has remained ever-present in England’s popular memory. In her impressive new book, Alison Weir has woven a detailed and intricate portrait of the last days of one of the most influential and important figures in English history.

Reviews:

-

Alison Weir’s deeply researched, thorough and unsensational examination of the last 4 dramatic months in Queen Anne Boleyn’s life is a page turning, illuminating and highly anxiety inducing read, even though we know the inevitable outcome. There are 3 major players in this drama, and the innocence and guilt of all are under question by posterity – and two of them, at the time, were not being judged in a court of law. Anne Boleyn, now Queen, was the woman Henry VIII had broken with the powerful Church of Rome for, in order to get his first marriage to Katherine of Aragon annulled. King Henry was an absolute monarch, and a million miles away from being any kind of benevolent dictator, though benevolence and dictatorship are an uneasy set of bedfellows anyway. Henry was far less dictator, in the end, than he was despot. At least, that is posterity’s verdict. Thomas Cromwell, son of a blacksmith, rather than of noble birth, Henry’s’Master Secretary’ was at this point the second most powerful person in the Kingdom, at least in a shadowy, behind the scenes, pulling the threads kind of way. Even, perhaps as much the puppet master as the ostensible real holder of the reins of power. However, holding the reins of power when the real ruler is as terrifying and at times as wilful a figure as Henry, is not a secure position. He that elevates those to power – particularly when they are not with the force of a noble family behind them – can as easily remove them from that position. And indeed, that did happen for Cromwell a few short years later. In a totalitarian state – and this was, many will be jostling to get close to the supremely powerful figure, and in this particular version of totalitarianism, that of absolute monarchy, the King is not only monarch, but is also Divine – so there is an extra layer of fear and superstition, that of offending against God, the risking of the immortal soul, if the highest of all has his will and majesty flouted. For those who jostle to climb the slippery pole of preferment, mainly through kicking and clawing and stabbing in the back those beneath you, or greasing the palms of those above you, there must always be the knowledge that today’s friend may join forces with yesterday’s enemy and be the one who kicks, claws and stabs you, because new and better alliances will always present themselves. The fickle finger of fate creates new martyrs and new figures to embody power and prestige. Much has been written of this horrific story. One of the many interesting facets of Weir’s book is her analysis of the changing viewpoints of culpability over the centuries. Anne, vilified as a combination of she-devil and whore at the time, later was seen as almost someone worthy of hagiography – a woman sinned against, not sinning, a woman who fell foul of a stitched -up court, a woman framed, and victim of injustice cynically carried out by the highest in the land. Later generations have seen her almost as a feminist martyr. She was, for sure, a powerful and intelligent woman, one outspoken, and by all accounts opinionated. She was certainly not content to play the role of passive, I-know-my-place-is-under-the-

foot-of-my-lord-and-master wifey which society expected. Such independence of spirit alone would be dangerous, whether or not the infidelities she was accused of were true or false, when her husband bore a fairly strong resemblance to that ogre of fairy-tale – Bluebeard. In fact, I did find myself wondering when that compelling and terrifying story originated, and from where. Anne was later seen as a kind of martyr for religious Reformism, as she was indeed, in the developing religious schisms between Rome and England, a Reformist, and championed the cause of reform. Whether Anne was, or was not guilty of the crimes as charged she was certainly not an unspotted open-hearted innocent. She, along with her family, like her replacement, Jane Seymour, along with her family, appeared to have an eye to the main chance. She showed little mercy to the rather more popular (with the people) Katherine of Aragon and her daughter Mary, and perhaps should not have been surprised that her husband, who had demonstrated all too readily little loyalty to a previous wife, was once again making space for a new venture into matrimony with one of the Queen’s ladies in waiting. Becoming a lady in waiting must almost have seemed like a sure route to becoming Queen, in Henry’s court – a kind of horizontal finishing school, perhaps! Jane Seymour, in her turn, played the main chance, though as she was fortunate enough to die in childbirth having given birth to a son she never had to face the possible demotion and vilification that might well have happened when Henry’s desires moved elsewhere. Anne was of course accused of adultery with 5 men and plotting the death of the king. Weir performs an elegant and persuasive analysis to show the charges were, at least in part, manufactured. The charges were very specific in terms of dates, places and times with the specific, named, individuals. Certainly some of the stated dates, places and partners were complete fabrications, as either Anne, or the accused lover, according to documentary evidence, were not at those places on those days, but documented as being elsewhere. She doesn’t say though that inappropriate behaviour and conversation by a Queen (according to the mores of the times) of some kind was definitely NOT occurring, but that evidence itself can show that some of the specified events could not have occurred as charged. What I particularly appreciated in this book is that she is very clear that to analyze the past by the ideas, mores and manners of the present is an activity which is fraught with danger. For example, some of the language used in some of Anne’s letters to those accused with her, and some of the language apparently used on the scaffold by her have been used to `prove’ her guilt – for example, the fact that in all her scaffold speeches the king is praised. There were courtly modes of address which would have been adhered to – and indeed, would have been recorded, whether or not they were uttered. And, as far as the speeches which any of the accused uttered before axes (in the case of the 5 men) or the sword (in Anne’s case) were wielded – it’s important to remember that totalitarian societies do not only punish those individuals it deems to have done wrong. You might know that whatever you say, you are about to face a brutal, painful death – there will be no reprieve from that – but what about those you leave behind, what about friends and family? Make too passionate a deathbed speech and you may very well be lining up those you love for savage punishment to come. The major, culpable figures are of course the two men, Cromwell and Henry. Again, different historians (given the fact that much documentary evidence from the time no longer exists) draw different conjectures as to which of the two was MOST guilty. Weir certainly deduces Cromwell was absolutely the one who created and faked, or merely deduced and collated the evidence, but the fact that he was responding to the way the wind was blowing, as far as Henry’s desires went. Henry was clearly tired of his wife and her inability to give him the necessary male heir to secure his kingdom, and as Cromwell had been a major player in securing Henry’s desired release from his first wife, no doubt Anne Boleyn’s fall from grace served both men well. We all see and hear what we want to hear and what we want to see. Neither Henry – nor any of the peers sitting in judgement on Anne and the men accused with her picked apart the holes in evidence. As one of those peers was Anne’s own father and another was her uncle, the dangers of coming to decisions which are not those the King desires, must be obvious. Particularly in the case of Anne’s father – he was condemning not only his daughter, but his son, as Anne’s brother Rochford was also one of those accused of adultery with her. How far all this suited Henry was shown by the fact that a mere 10 days after Anne’s execution he had married Jane Seymour. I have read some reviews where the reviewer feels that Weir castigates Cromwell for too much, and that she `whitewashes’ Henry. I must say I did not get any sense of a Henry `whitewash’ – Weir does however try to think herself into people in their time. In that Tudor court, the terrible events of The Wars Of The Roses and an insecure succession were not that long ago. Succession happened through sons, not daughters, so the importance of a male heir felt paramount. And this was also still a highly superstitious age. Credulity existed for sure, and could also be no doubt evoked to dupe oneself as well as others. Henry was out of love with a woman he had been mad for. She was getting older and other than her first born, seemed unable to carry a child to term. Rather than looking at your own libidinous, greedy and fickle nature to explain the dreadful mistake made in your marriage choices, `being bewitched’ might have seemed an explanation which had a logic which would not wash today, but probably did in those times. Something I found absolutely fascinating in this book is that Weir lays out for us the enormously conflicting evidence which is available from eyewitnesses, over-hearers and those who were onlookers or participants. This really indicates the huge difficulties in historical research and deduction – which, the further back in time one travels, gets even harder. Even something as theoretically simple as what Anne was wearing at her public execution is differently described by those who were there to see it all – sometimes, even disparities in the colour, never mind the fabric and decoration of her death dress. And as for the very very different transcriptions of what she said in her `from the scaffold’ speech – extraordinary! Of course, in an age where not only were there no recording devices, but no microphones, and crucially, not even any system of shorthand notation, it would be nigh on impossible to note down verbatim what someone was saying. Not to mention the fact that the high emotional anxiety of Anne, not to mention any listeners close enough to properly hear what she was saying, would have rendered memory and observation extremely suspect. No doubt acceptable spin was as active in Tudor times as it is today. I recommend this book most highly. It combines obviously exhaustive research with clarity about rationale for interpretation, which has to be done as so little documentation actually exists about the lead up and the planning and what went on behind closed doors, obviously in secret. Weir is neither dry in her laying out of research, nor is she sensationalist – she leaves the truly sensationalist events themselves to create the jaw-dropping, gut-sickening responses which any reader of any kind of empathy and imagination will have. I was so, so pleased that her recording of what actually happened in those dreadful, savage executions was delivered sparely and un-emotively, without overblown descriptors designed to titivate a kind of delight-in-horror entertainment. The events themselves are far more horrific, and bring it all to enough life, without the cheapness of creating revved-up fiction I’m left uneasily feeling that though on one level we are far far away from the savagery and terror of that Tudor court, in some ways, it seems uncomfortably close, in a world where women can still be the recipients of savage double-standard sentences for transgressing the mores of their society, and where totalitarian states, whether espousing religious or political ideology despotism, dispense savage punishment against individuals and groups who dare to dissent. Weir gave me pause to think about much more than the last four months of Anne Boleyn’s life. -

Most people have heard of Anne Boleyn. A majority of people will also know she was executed, even that she died by beheading. Why was she executed? The oft repeated legend is that Anne failed to produce a son. If this is legend then how did a queen consort, perhaps the most important in English history, end up arrested, convicted of treason, and executed. Was it Thomas Cromwell neutralising his enemies? A king desperate to re-marry Jane Seymour? Or, was Anne guilty? Alison Weir is a popular narrative historian, who has written several books on Tudor history, but her 2009 effort, The Lady in the Tower: the Fall of Anne Boleyn is by far my favourite. There are copious books on Anne Boleyn. Eric Ives’s biography is often considered the best. Ives certainly gave the most detailed investigation of her remarkable downfall, and the “coup theory” that Weir believes sealed her fate. However, Weir has written the first volume solely centred around spring 1536 and the dramatic fall. Weir has quite a task on her hands. Dealing with such a tight time frame, not many authors could pull off such a coherent summarisation. Such a short time frame also gives her opportunities to go into greater detail. For me the gem rests in the seven men arrested with Anne, five of whom would die, are often footnotes relegated to odd paragraphs. We look a lot more into Sir Francis Weston, Henry Norris, William Brereton and Mark Smeaton so we see them more humanised. I do not share Weir’s view on Anne’s fall. The theory proposed by both Dr Walker and Dr Lipscomb has always seemed the likeliest. However, I enjoyed reading Alison’s investigation and analysis of the evidence. This is, as Weir states, judicial murder. Of course, there is no proof, as Weir concludes: ‘she was executed in accordance with the law as it then stood’ but concluding later, ‘in weighing up the evidence for and against her, the historian cannot but conclude that Anne Boleyn was the victim of a dreadful miscarriage of justice: and not only Anne and the men accused with her, but also the King himself…’ The chapter on Anne’s execution was quite moving – a strange thing, really. When you’ve read as many biographies as I have, there is an element of desensitising. Here one comes face to face with the awfulness of knowing you are going to your death, and the expectancy. One can almost feel the tension and awesomeness that drove all but the Duke of Suffolk and Henry’s bastard, the Duke of Richmond, to their knees as they watched (something that wasn’t normal, despite popular myth). Most moving though was the chapter on Elizabeth, ‘the Concubine’s little bastard’. This is a very good book, one for the connoisseur and otherwise, that reads like an intense thriller made more tangible by being true life. I don’t necessarily agree that Anne was “shrewish and volatile” but Alison Weir pulls off a tour de force, expanding what other books cannot, due to size, whilst maintaining a contextualized and balanced account on a decisive point in British and European, and even women’s, history.

The Author, Alison Weir was born in London and now resides in Surrey. Before becoming a published author in 1989, she was a civil servant, then a housewife and mother. From 1991 to 1997, whilst researching and writing books, she ran a school for children with learning difficulties, before taking up writing full-time. Her books include The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Lancaster and York, Children of England, Elizabeth the Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Mary, Queen of Scots, Henry VIII: King and Court, Isabella and, most recently Katherine Swynford.

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend