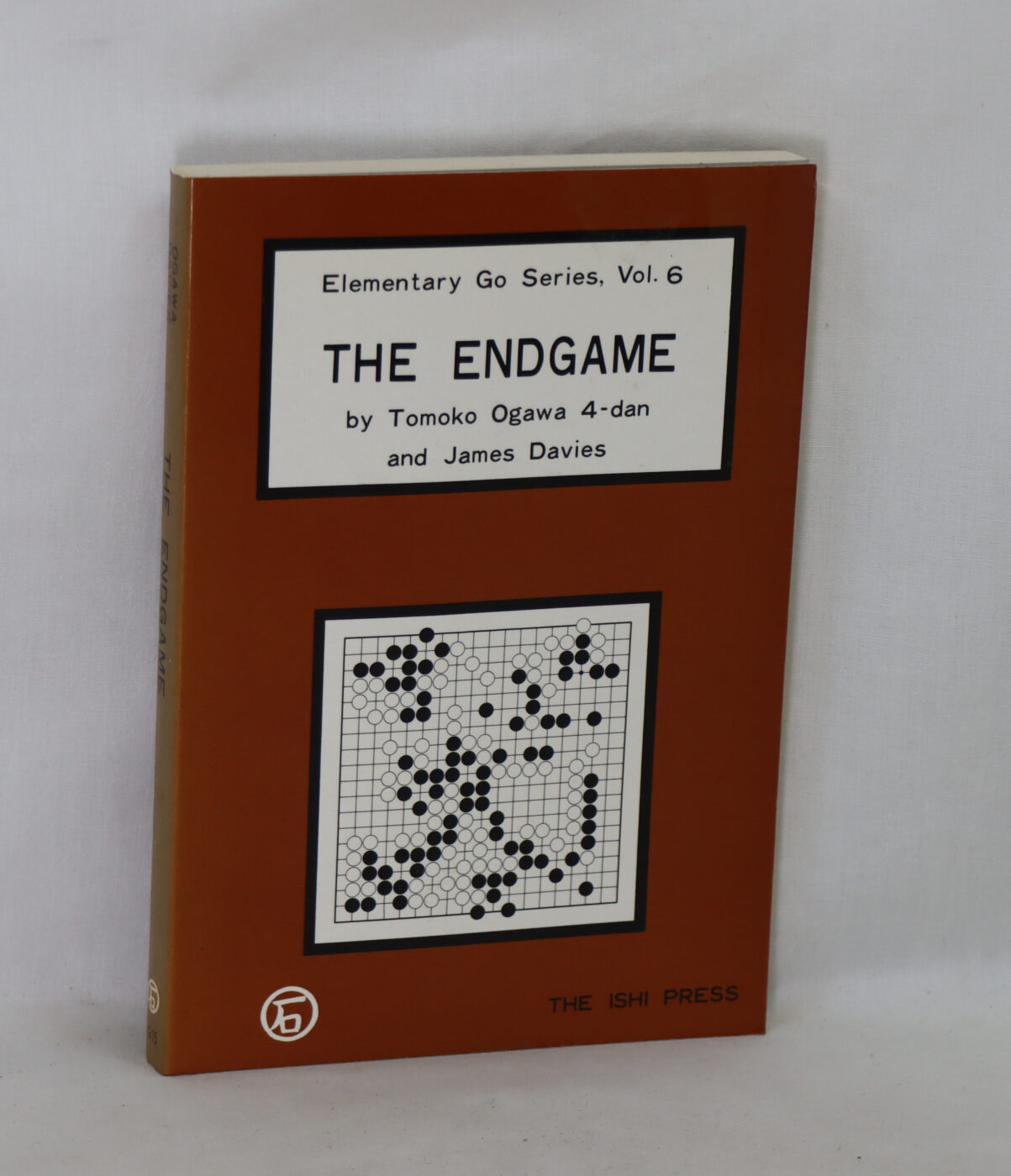

The Endgame. Elementary Go Series, Vol 6.

By Tomoko Ogawa

ISBN: 9784906574155

Printed: 1982

Publisher: The Ishi Press. Tokyo

| Dimensions | 11 × 18 × 1 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 11 x 18 x 1

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Paperback. Brown cover with black title.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

A FROST PAPERBACK is a loved book which a member of the Frost family has checked for condition, cleanliness, completeness and readability. When the buyer collects their book, the delivery charge of £3.00 is not made

The endgame tends to be the neglected side of the game of go. This is strange indeed, for it also tends to be where the outcome is decided, and frequently accounts for about half the stones played. This volume, by a Japanese professional go player and a strong American amateur, seeks to rectify this situation by setting forth the basic tactics, strategies and counting techniques needed in the endgame. Everything from the smallest local tesujis to the global macroendgame is covered. With numerous examples and problems, many of them drawn from the Japanese author’s professional games. The reader is encouraged to think for himself and, by doing so, will certainly become stronger.

Go is an abstract strategy board game for two players in which the aim is to fence off more territory than the opponent. The game was invented in China more than 2,500 years ago and is believed to be the oldest board game continuously played to the present day. A 2016 survey by the International Go Federation’s 75 member nations found that there are over 46 million people worldwide who know how to play Go, and over 20 million current players, the majority of whom live in East Asia.

The playing pieces are called stones. One player uses the white stones and the other black stones. The players take turns placing their stones on the vacant intersections (points) on the board. Once placed, stones may not be moved, but captured stones are immediately removed from the board. A single stone (or connected group of stones) is captured when surrounded by the opponent’s stones on all orthogonally adjacent points. The game proceeds until neither player wishes to make another move.

When a game concludes, the winner is determined by counting each player’s surrounded territory along with captured stones and komi (points added to the score of the player with the white stones as compensation for playing second). Games may also end by resignation.

The standard Go board has a 19×19 grid of lines, containing 361 points. Beginners often play on smaller 9×9 or 13×13 boards, and archaeological evidence shows that the game was played in earlier centuries on a board with a 17×17 grid. The 19×19 board had become standard by the time the game reached Korea in the 5th century CE and Japan in the 7th century CE.

Go was considered one of the four essential arts of the cultured aristocratic Chinese scholars in antiquity. The earliest written reference to the game is generally recognized as the historical annal Zuo Zhuan (c. 4th century BCE).

Despite its relatively simple rules, Go is extremely complex. Compared to chess, Go has a larger board with more scope for play, longer games, and, on average, many more alternatives to consider per move. The number of legal board positions in Go has been calculated to be approximately 2.1×10170, which is far greater than the number of atoms in the observable universe, which is estimated to be on the order of 1080.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend