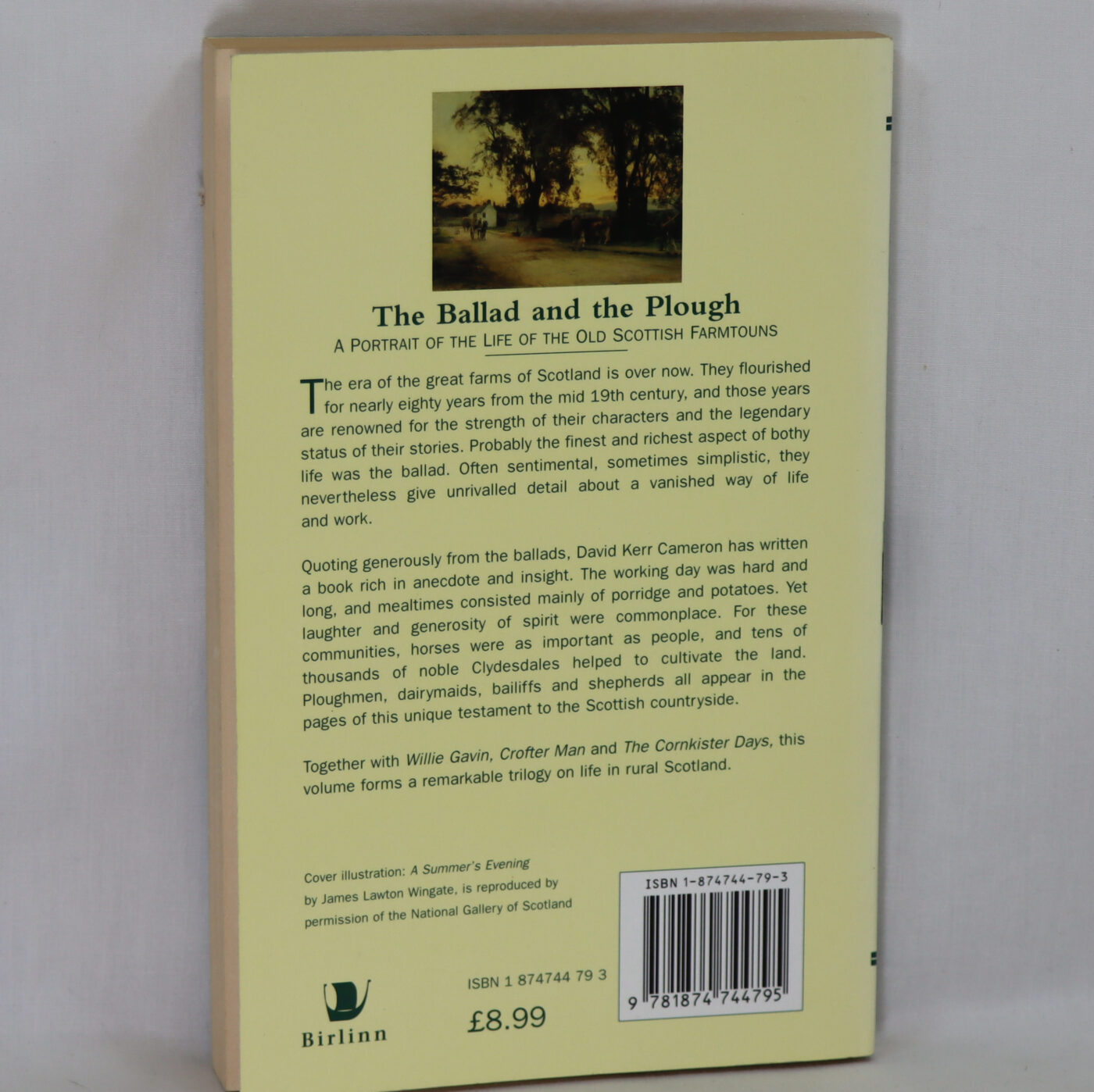

The Ballad and the Plough.

By David Kerr Cameron

ISBN: 9780857903280

Printed: 1997

Publisher: Birlinn Books. Edinburgh

| Dimensions | 14 × 21 × 2 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 14 x 21 x 2

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Paperback. Cream cover with black title and farmyard painting.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- This used book has a £3 discount when collected from our shop

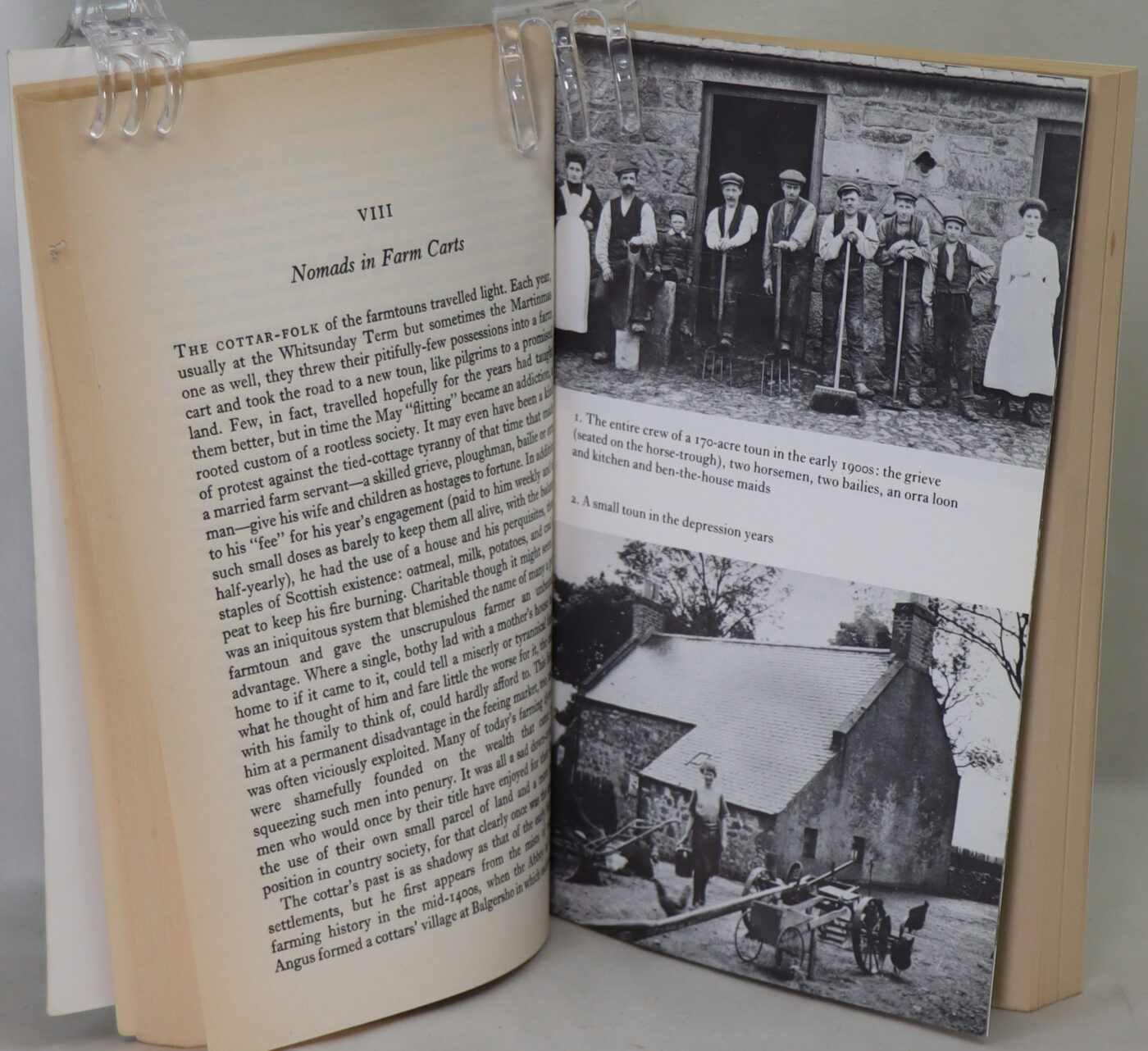

For conditions, please view the photographs. The era of the great farms of Scotland is over now. They flourished for nearly eighty years from the mid 19th century, and those years are renowned for the strength of their characters and the legendary status of their stories. Probably the finest and richest aspect of ‘bothy’ life was the ballad. Often sentimental, sometimes simplistic, they nevertheless give unrivalled detail about a vanished way of life and work. Quoting generously from the ballads, David Kerr Cameron has written a book rich in anecdote and insight. The working day was hard and long, and mealtimes consisted mainly of porridge and potatoes. Yet laughter and generosity of spirit were commonplace. For these communities, horses were as important as people, and tens of thousands of noble Clydesdales helped to cultivate the land. Ploughmen, dairymaids, bailiffs and shepherds all appear in the pages of this unique testament to the Scottish countryside. Together with Willie Gavin, Crofter Man and The Cornkister Days, this volume forms a remarkable trilogy on life in rural Scotland.

Review: One of the constant joys of books – and reading – is that they provide so much enjoyment and knowledge for such little outlay. The plainest and least expensive books can provide the greatest pleasure to the reader. The edition of “The Ballad and the Plough” that I recently bought from an online bookseller is just an inexpensive 1970s mass market paperback, but reading it is a rare treat. The author, David Kerr Cameron, was brought up in the early years of the 20th century on one of the “farmtouns” of the north east lowlands of Scotland and went on to train and work as a journalist. This combination of personal experience and journalistic skill produced a book that is a fine record of Scottish farming from the mid-19th century to the early 1930s from a writer who would clearly have made an excellent professional historian. It’s also an elegy, with clarity of vision and without undue sentimentality, for a way of life that has now almost completely vanished. I say “almost” because there is still one British farm that exclusively uses horses to work the land, the last little thread connecting us with the world described in this book. The farmtouns were self-contained units, almost like ships at sea, in vast, often hard and unyielding Scottish landscapes. It was only the constant effort sustained by the farmtoun “crew” day in, day out, and year in, year out that produced the grain, milk and meat that made Scotland a leader in world farming for nearly a century. That success came at a price, though; and it was usually paid by the youngest and most vulnerable workers. They lived in bothies, or, in some parts, “chaumers”, the condition of which was often far below that of the stables of the horses who worked alongside them. The lives of the members of the crew, the ploughmen, bothy lads, dairymaids, cottars’ wives, shepherds, grieves and bailies, were recorded in the Bothy Ballads. These songs of loving and losing, skill and chicanery, mean farmers and their even meaner wives (and kindly employers too), harvests and ploughing matches, fights and fairs are included in this book. They are more than records, though, for as Cameron reveals, they also circulated valuable information about employers and conditions of employment to the land workers as they moved about the countryside.The detail in this book is such that it provides an invaluable resource for the social and economic historian of those times; but it is most certainly not at the expense of style or readability. For instance, this is Cameron on the farming year: “Potatoes were dug from their drills and gathered, to be stored in clamps in the corners of the fields like barrows of the ancient dead; turnips sat in their rows fattening like yellow emperors – till they were plucked from them in the winter frosts to feed beasts in the byre.” And as with John McNeillie’s book, “Wigtown Ploughman”, the stark beauty of the land lays claim to those who work on it, whether they will or no: “The grieve might order the farmtoun day but God and the soil itself set the rhythm of the working year. Though he might well have ridiculed the notion, that awareness etched itself deep into a man’s soul instilling a feel for the land and its changing scene, the melancholy of a winter landscape. About a farmtoun, in time, a man came to know where he stood in the universe.” Reading books such as this strips away any remaining illusions that the reader might have about a rosy agrarian past; but it is a significant part of Scottish and British history that is best understood through writers with direct experience such as Cameron.

David Kerr Cameron was himself born into a crofting family in the north-east of Scotland and there he experienced at first hand the last days of that harsh way of life. He worked most of his life as a journalist, including 22 years spent in London. He died in 2002.

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend