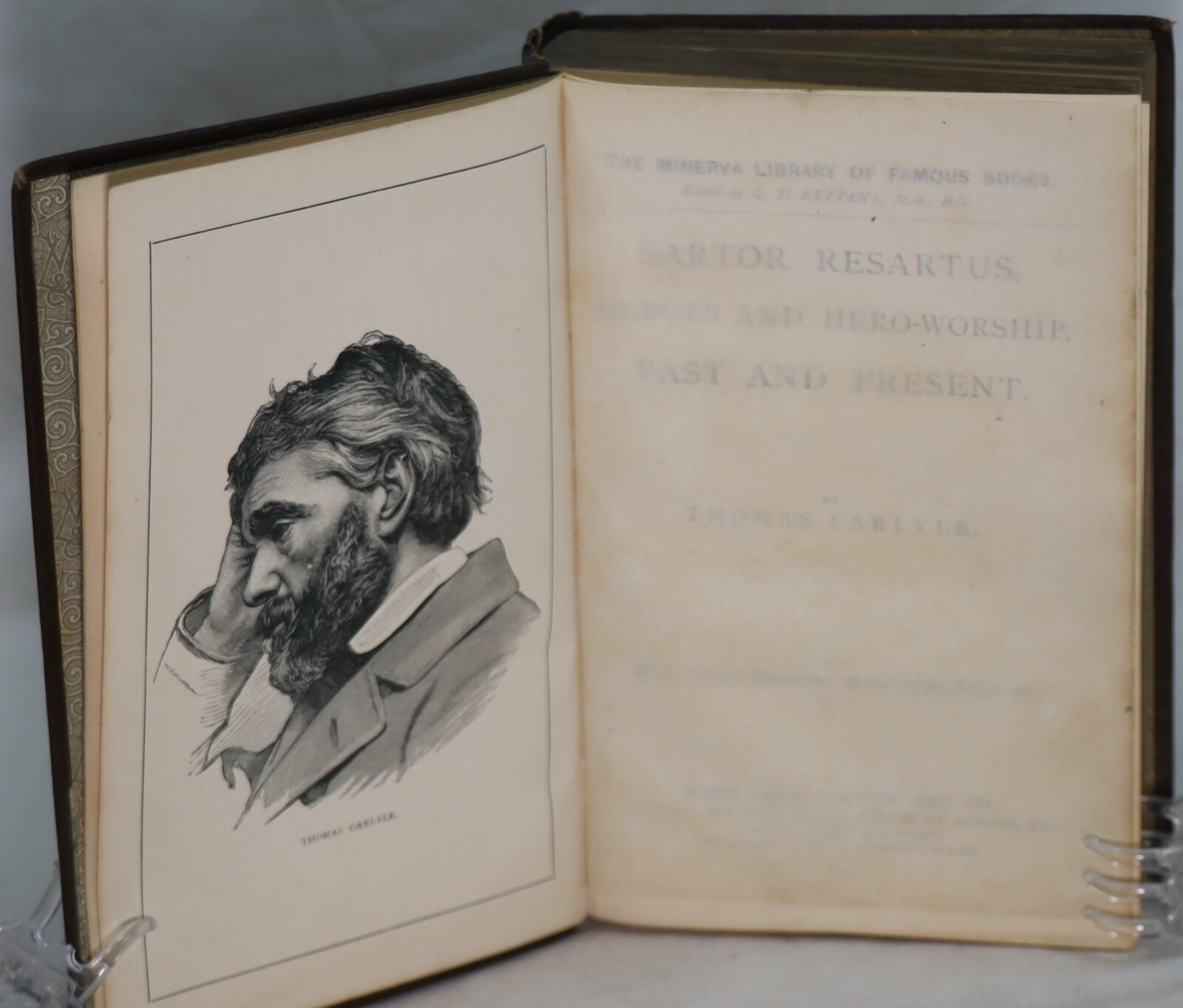

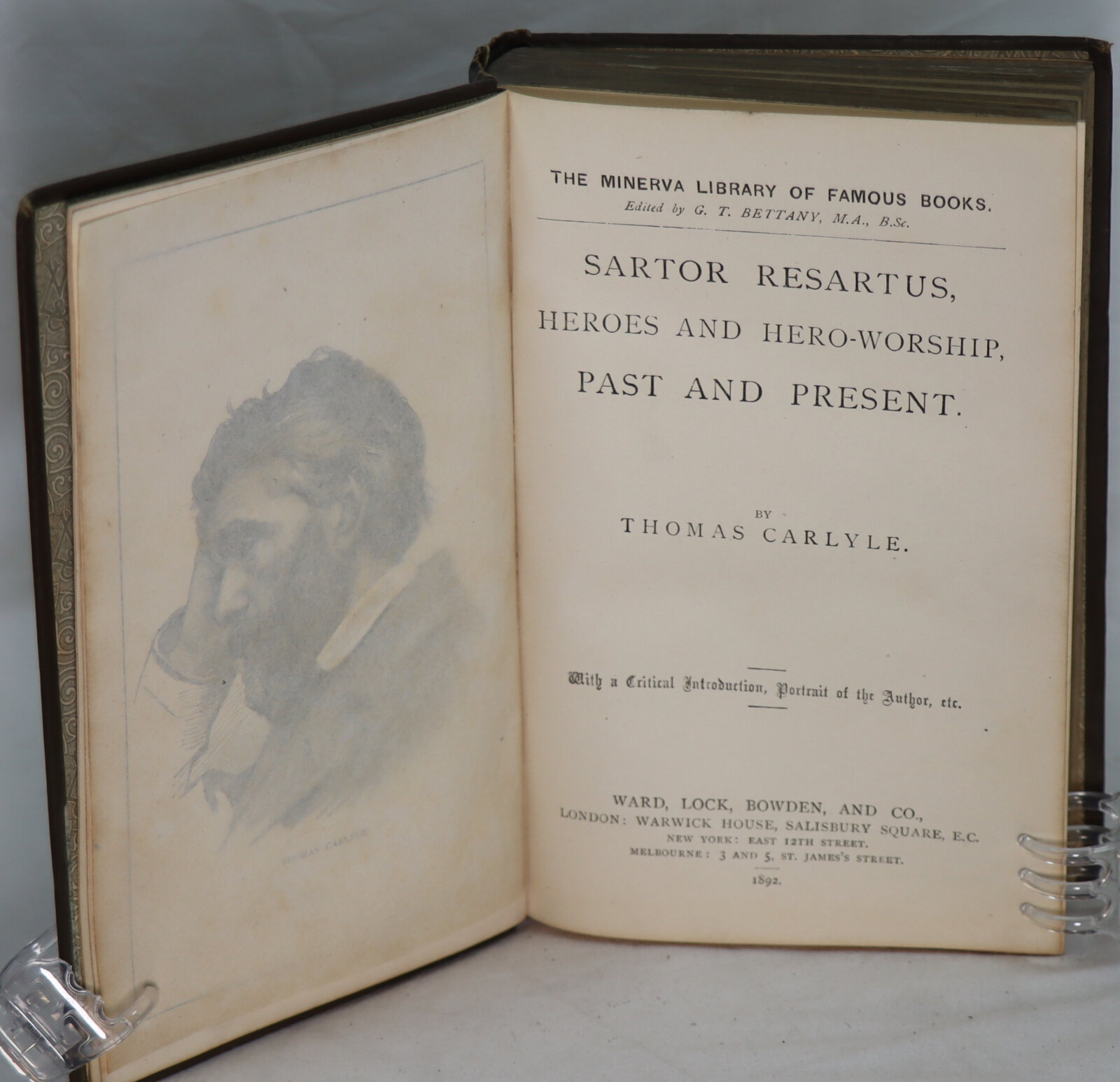

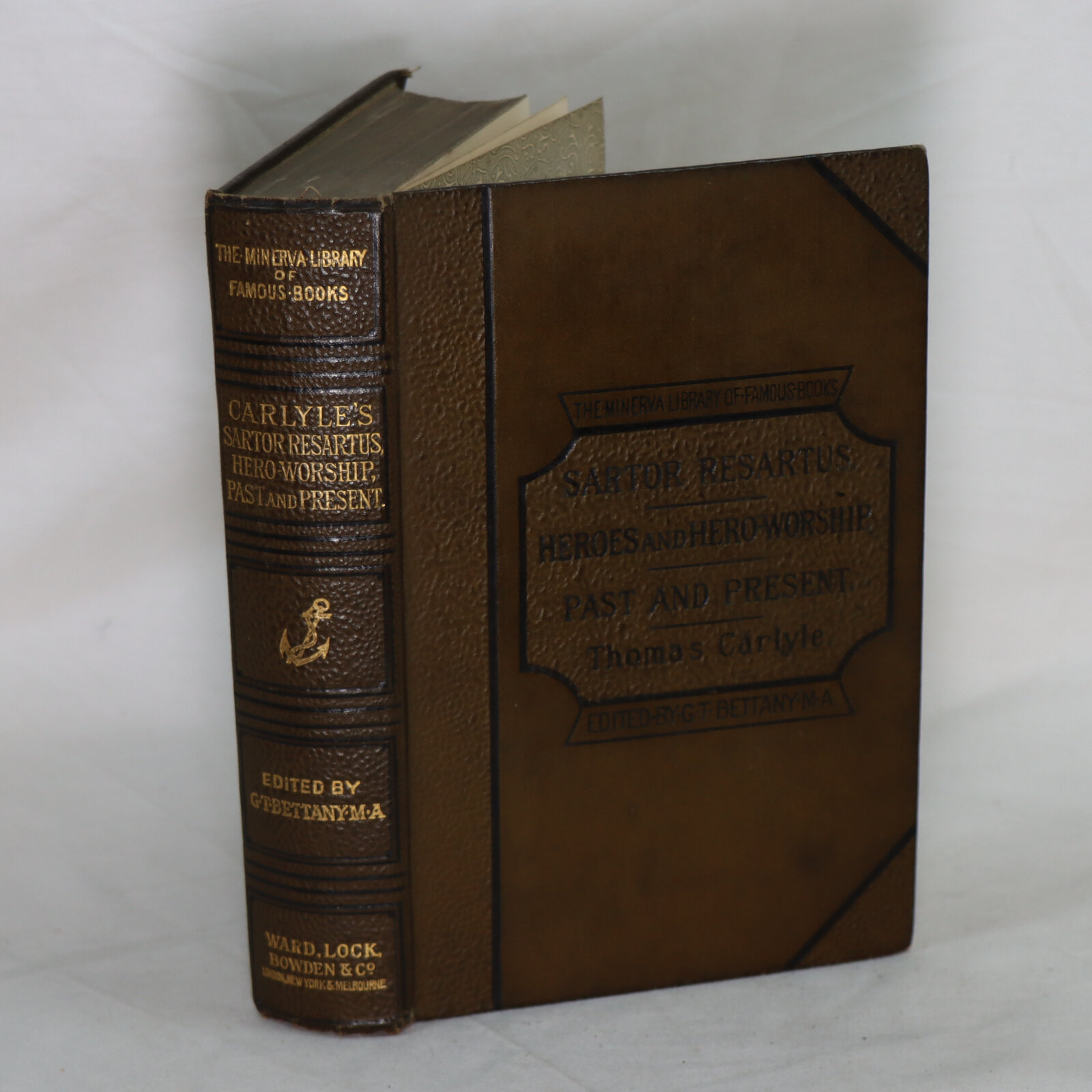

Sartor Resartus, Heroes and Hero-Worship, Past and Present.

By Thomas Carlyle

Printed: 1892

Publisher: Ward Lock Howden & Co. London

| Dimensions | 13 × 18 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 13 x 18 x 3

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Green cloth binding with gilt title on the spine and the front board.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

-

Note: This book carries the £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

-

Inscribed 1892. The Minerva Library of Famous Books.

Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books is an 1831 novel by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in Fraser’s Magazine in November 1833 – August 1834. The novel purports to be a commentary on the thought and early life of a German philosopher called Diogenes Teufelsdröckh (which translates as ‘Zeus-born Devil’s-dung’ [the referenced quotation has Diogenes as ‘God-born’, but that is not strictly accurate), author of a tome entitled Clothes: Their Origin and Influence. Teufelsdröckh’s Transcendentalist musings are mulled over by a sceptical English Reviewer (referred to as Editor) who also provides fragmentary biographical material on the philosopher. The work is, in part, a parody of Hegel, and of German Idealism more generally.

On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History is a book by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, published by James Fraser, London, in 1841. It is a collection of six lectures given in May 1840 about prominent historical figures. It lays out Carlyle’s belief in the importance of heroic leadership. Carlyle was one of the few philosophers who lived through the British industrial revolution but maintained a non-materialistic view of historical development. The book included lectures discussing people ranging from the field of religion through to literature and politics. The figures chosen for each lecture were presented by Carlyle as archetypal examples of individuals who, in their respective fields of endeavour, had dramatically impacted history in some way. The Islamic prophet Muhammad found a place in the book in the lecture titled “The Hero as Prophet”. In his work, Carlyle outlined Muhammad as a Hegelian agent of reform, insisting on his sincerity and commenting “how one man single-handedly, could weld warring tribes and wandering Bedouins into a most powerful and civilized nation in less than two decades”. His interpretation has been widely cited by Muslim scholars to show Muhammad without orientalist bias.

Monument to Thomas Carlyle by William Kellock Brown, Kelvingrove Park, Glasgow

Carlyle held that “Great Men should rule and that others should revere them,”a view that for him was supported by a complex faith in history and evolutionary progress. Societies, like organisms, evolve throughout history, thrive for a time, but inevitably become weak and die out, giving place to a stronger, superior breed. Heroes are those who affirm this life process, accepting its cruelty as necessary and thus good. For them courage is a more valuable virtue than love; heroes are noblemen, not saints. The hero functions first as a pattern for others to imitate, and second as a creator, moving history forwards not backward (history being the biography of great men). Carlyle was among the first of his age to recognize that the death of God is in itself nothing to be happy about, unless man steps in and creates new values to replace the old. For Carlyle, the hero should become the object of worship, the centre of a new religion proclaiming humanity as “the miracle of miracles… the only divinity we can know”. For Carlyle’s creed Bentley proposes the name “heroic vitalism”, a term embracing both a political theory, aristocratic radicalism, and a metaphysic, supernatural naturalism. The heroic vitalists feared that the recent trends toward democracy would hand over power to the ill-bred, uneducated, and immoral, whereas their belief in a transcendent force in nature directing itself onward and upward gave some hope that this overarching force would overrule in favor of the strong, intelligent, and noble.

For Carlyle, the hero was somewhat similar to Aristotle’s “magnanimous” man – a person who flourished in the fullest sense. However, for Carlyle, unlike Aristotle, the world was filled with contradictions with which the hero had to deal. All heroes will be flawed. Their heroism lay in their creative energy in the face of these difficulties, not in their moral perfection. To sneer at such a person for their failings is the philosophy of those who seek comfort in the conventional. Carlyle called this “valetism”, from the expression “no man is a hero to his valet”.

Past and Present is a book by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle. It was published in April 1843 in England and the following month in the United States. It combines medieval history with criticism of 19th-century British society. Carlyle wrote it in seven weeks as a respite from the harassing labor of writing Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches. He was inspired by the recently published Chronicles of the Abbey of Saint Edmund’s Bury, which had been written by Jocelin of Brakelond at the close of the 12th century. This account of a medieval monastery had taken Carlyle’s fancy, and he drew upon it in order to contrast the monks’ reverence for work and heroism with the sham leadership of his own day. Lord Acton called it “the most remarkable piece of historical thinking in the language.” G. K. Chesterton considered it along with Chartism (1839) to be “the work [Carlyle] was chosen by gods and men to achieve”.

Past and Present contributed to several social developments in the 19th and early-20th centuries, including the decline of laissez-faire, the crafting and passage of the Factory Acts, the Elementary Education Act 1870, and the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act, the emigration of labourers from England to the United States during the Great Rapprochement, the rise of practices such as business ethics, profit sharing, and the redistribution of income and wealth, the establishment of state education, and even playgrounds.

Carlyle’s influence on modern socialism can be seen most acutely in the response to Past and Present. New Moral World, the official newspaper of the Owenite movement, published a six-part review by then-editor George Fleming between August and November 1843, further issuing an additional excerpt two months afterwards. Fleming expressed “gratification in finding . . . the true philosophy of Socialism . . . arrayed in the gorgeous and striking drapery of Carlyleism.” Fleming believed that a “new, unexpected, and powerful ally to our cause has come into the field”, finding in the work “identical principles with those of [Robert Owen]”, portraying Carlyle as a covert socialist that has infiltrated the “charmed circle” of high society. In January 1844, Friedrich Engels published an extensive, laudatory review in the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher. He wrote that Carlyle’s acute analysis of the social question in England made it the only book by a contemporary educated Englishman worth reading. Engels praised Carlyle’s humanitarian point of view yet considered it only a nonscientific preliminary to socialism. He characterized Carlyle as a German pantheist and a romantic Tory, a follower of Schelling rather than of Hegel, too hung up on religion and the myth of aristocratic leadership to accept freedom and self-determination as the ultimate aim of history, while expressing hope that Carlyle would overcome these limitations.

The book greatly influenced the development of medievalism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. John William Mackail wrote that during William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones’ days at Oxford, “Carlyle’s Past and Present stood alongside Modern Painters as inspired and absolute truth.” John Ruskin gifted his personal, extensively annotated copy to a friend in 1887, along with a letter in which he called it “a book which I read no more because it has become a part of myself, and my old marks in it are now useless, because in my heart I mark it all.” Fors Clavigera has been called “in effect the resumption of the concerns of Carlyle’s Past and Present in another form.”

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 1795 – 5 February 1881) was a British essayist, historian, and philosopher from the Scottish Lowlands. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature, and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Scotland, Carlyle attended the University of Edinburgh where he excelled in mathematics, inventing the Carlyle circle. After finishing the arts course, he prepared to become a minister in the Burgher Church while working as a schoolmaster. He quit these and several other endeavours before settling on literature, writing for the Edinburgh Encyclopædia and working as a translator. He found initial success as a disseminator of German literature, then little-known to English readers, through his translations, his Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825), and his review essays for various journals. His first major work was a novel entitled Sartor Resartus (1833–34). After relocating to London, he became famous with his French Revolution (1837), which prompted the collection and reissue of his essays as Miscellanies. Each of his subsequent works, including On Heroes (1841), Past and Present (1843), Cromwell’s Letters (1845), Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850), and History of Frederick the Great (1858–65), were highly regarded throughout Europe and North America. He founded the London Library, contributed significantly to the creation of the National Portrait Galleries in London and Scotland,was elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University in 1865, and received the Pour le Mérite in 1874, among other honours.

Carlyle occupied a central position in Victorian culture, being considered not only, in the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the “undoubted head of English letters”, but a “secular prophet”. Posthumously, his reputation suffered as publications by his friend and disciple James Anthony Froude provoked controversy about Carlyle’s personal life, particularly his marriage to Jane Welsh Carlyle. His reputation further declined in the 20th century, as the onsets of World War I and World War II brought forth accusations that he was a progenitor of both Prussianism and fascism. Since the 1950s, extensive scholarship in the field of Carlyle Studies has improved his standing, and he is now recognised as “one of the enduring monuments of our literature who, quite simply, cannot be spared.

Want to know more about this item?

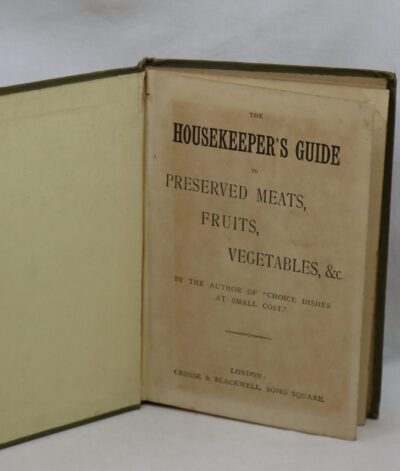

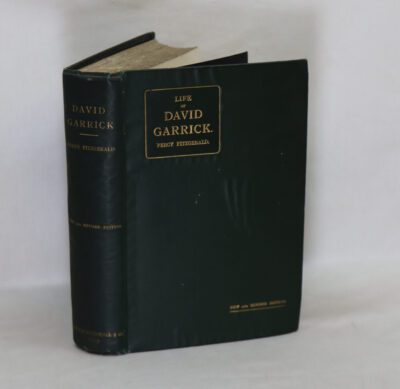

Related products

Share this Page with a friend