Q.Horatius. Opera A Mauricio Hauptio.

By Quintus.Horatius Flaccus

Printed: 1861

Publisher: Apud S Hirzelium. Lispiae

| Dimensions | 9 × 14 × 2 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: Latin

Size (cminches): 9 x 14 x 2

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

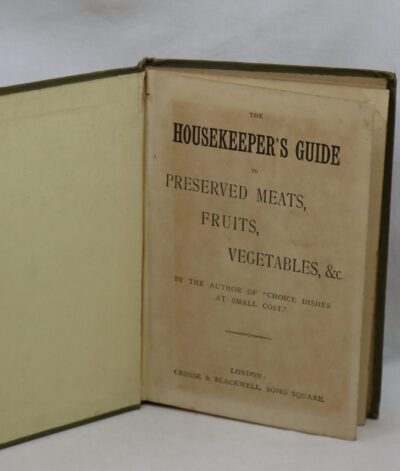

Cream calf binding with black and red title on the spine. All edges gilt.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

A lovely copy.

This is ‘Opera A Mauricio Hauptio’ by Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace) who was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. Published by Lipsiae, Apud 8 Hirzelium, in latin, in 1861.

Horace in an anonymous late 18th to early 19th century engraving

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC), commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his Odes as just about the only Latin lyrics worth reading: “He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words.”

Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Satires and Epistles) and caustic iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are amusing yet serious works, friendly in tone, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: “as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings”.

His career coincided with Rome’s momentous change from a republic to an empire. An officer in the republican army defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian’s right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was “a master of the graceful sidestep”) but for others he was, in John Dryden’s phrase, “a well-mannered court slave”.

The reception of Horace’s work has varied from one epoch to another and varied markedly even in his own lifetime. Odes 1–3 were not well received when first ‘published’ in Rome, yet Augustus later commissioned a ceremonial ode for the Centennial Games in 17 BC and also encouraged the publication of Odes 4, after which Horace’s reputation as Rome’s premier lyricist was assured. His Odes were to become the best received of all his poems in ancient times, acquiring a classic status that discouraged imitation: no other poet produced a comparable body of lyrics in the four centuries that followed (though that might also be attributed to social causes, particularly the parasitism that Italy was sinking into). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ode-writing became highly fashionable in England and a large number of aspiring poets imitated Horace both in English and in Latin.

In a verse epistle to Augustus (Epistle 2.1), in 12 BC, Horace argued for classic status to be awarded to contemporary poets, including Virgil and apparently himself. In the final poem of his third book of Odes he claimed to have created for himself a monument more durable than bronze (“Exegi monumentum aere perennius”, Carmina 3.30.1). For one modern scholar, however, Horace’s personal qualities are more notable than the monumental quality of his achievement:

… when we hear his name we don’t really think of a monument. We think rather of a voice which varies in tone and resonance but is always recognizable, and which by its unsentimental humanity evokes a very special blend of liking and respect. — Niall Rudd

Yet for men like Wilfred Owen, scarred by experiences of World War I, his poetry stood for discredited values:

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The Old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

The same motto, Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, had been adapted to the ethos of martyrdom in the lyrics of early Christian poets like Prudentius.

These preliminary comments touch on a small sample of developments in the reception of Horace’s work.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend