Pindar: The Olympian and Pythian Odes.

By C A M Fennell

Printed: 1893

Publisher: University press. Cambridge

Edition: New edition

| Dimensions | 13 × 19 × 2 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 13 x 19 x 2

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Item information

Description

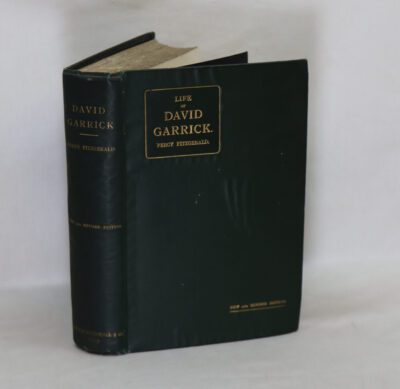

Brown cloth binding with gilt title on the spine.

- We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

‘There is nothing in the whole range of literature corresponding to the Greek odes of victory, the most splendid examples of which still surviving were composed by Pindar between the years 502 and 442 B.C., during the most flourishing period of the Greeks’ history, and in the high summer of their genius.’

A very rare quality text book in very good order as the photographs display.

Pindar was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, “Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar is by far the greatest, in virtue of his inspired magnificence, the beauty of his thoughts and figures, the rich exuberance of his language and matter, and his rolling flood of eloquence, characteristics which, as Horace rightly held, make him inimitable.” His poems can also, however, seem difficult and even peculiar. The Athenian comic playwright Eupolis once remarked that they “are already reduced to silence by the disinclination of the multitude for elegant learning”. Some scholars in the modern age also found his poetry perplexing, at least until the 1896 discovery of some poems by his rival Bacchylides; comparisons of their work showed that many of Pindar’s idiosyncrasies are typical of archaic genres rather than of only the poet himself. His poetry, while admired by critics, still challenges the casual reader and his work is largely unread among the general public.

Pindar was the first Greek poet to reflect on the nature of poetry and on the poet’s role. His poetry illustrates the beliefs and values of Archaic Greece at the dawn of the Classical period. Like other poets of the Archaic Age, he has a profound sense of the vicissitudes of life, but he also articulates a passionate faith in what men can achieve by the grace of the gods, most famously expressed in the conclusion to one of his Victory Odes:

Creatures of a day! What is anyone?

What is anyone not? A dream of a shadow

Is our mortal being. But when there comes to men

A gleam of splendour given of heaven,

Then rests on them a light of glory

And blessed are their days. (Pythian 8)

In his first Pythian ode, composed in 470 BC in honour of the Sicilian tyrant Hieron, Pindar celebrated a series of victories by Greeks against foreign invaders: Athenian and Spartan-led victories against Persia at Salamis and Plataea, and victories by the western Greeks led by Theron of Acragas and Hieron against the Carthaginians and Etruscans at the battles of Himera and Cumae. Such celebrations were not appreciated by his fellow Thebans: they had sided with the Persians and had incurred many losses and privations as a result of their defeat. His praise of Athens with such epithets as bulwark of Hellas (fragment 76) and city of noble name and sunlit splendour (Nemean 5) induced the authorities in Thebes to fine him 5,000 drachma, to which the Athenians are said to have responded with a gift of 10,000 drachma. According to another account, the Athenians even made him their proxenus or consul in Thebes. His association with the fabulously rich Hieron was another source of annoyance at home. It was probably in response to Theban sensitivities over this issue that he denounced the rule of tyrants (i.e. rulers like Hieron) in an ode composed shortly after a visit to Hieron’s sumptuous court in 476–75 BC (Pythian 11).

Pindar’s actual phrasing in Pythian 11 was “I deplore the lot of tyrants” and though this was traditionally interpreted as an apology for his dealings with Sicilian tyrants like Hieron, an alternative date for the ode has led some scholars to conclude that it was in fact a covert reference to the tyrannical behaviour of the Athenians, although this interpretation is ruled out if we accept the earlier note about covert references. According to yet another interpretation Pindar is simply delivering a formulaic warning to the successful athlete to avoid hubris. It is highly unlikely that Pindar ever acted for Athenians as their proxen or consul in Thebes.

Lyric verse was conventionally accompanied by music and dance, and Pindar himself wrote the music and choreographed the dances for his victory odes. Sometimes he trained the performers at his home in Thebes, and sometimes he trained them at the venue where they performed. Commissions took him to all parts of the Greek world – to the Panhellenic festivals in mainland Greece (Olympia, Delphi, Corinth and Nemea), westwards to Sicily, eastwards to the seaboard of Asia Minor, north to Macedonia and Abdera (Paean 2) and south to Cyrene on the African coast. Other poets at the same venues vied with him for the favours of patrons. His poetry sometimes reflects this rivalry. For example, Olympian 2 and Pythian 2, composed in honour of the Sicilian tyrants Theron and Hieron following his visit to their courts in 476–75 BC, refer respectively to ravens and an ape, apparently signifying rivals who were engaged in a campaign of smears against him – possibly the poets Simonides and his nephew Bacchylides. Pindar’s original treatment of narrative myth, often relating events in reverse chronological order, is said to have been a favourite target for criticism. Simonides was known to charge high fees for his work and Pindar is said to have alluded to this in Isthmian 2, where he refers to the Muse as “a hireling journeyman”. He appeared in many poetry competitions and was defeated five times by his compatriot, the poet Corinna, in revenge of which he called her Boeotian sow in one of his odes (Olympian 6. 89f.).

It was assumed by ancient sources that Pindar’s odes were performed by a chorus, but this has been challenged by some modern scholars, who argue that the odes were in fact performed solo. It is not known how commissions were arranged, nor if the poet travelled widely: even when poems include statements like “I have come” it is not certain that this was meant literally. Uncomplimentary references to Bacchylides and Simonides were found by scholars but there is no reason to accept their interpretation of the odes. In fact, some scholars have interpreted the allusions to fees in Isthmian 2 as a request by Pindar for payment of fees owed to himself. His defeats by Corinna were probably invented by ancient commentators to account for the Boeotian sow remark, a phrase moreover that was completely misunderstood by scholiasts, since Pindar was scoffing at a reputation that all Boeotians had for stupidity.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend