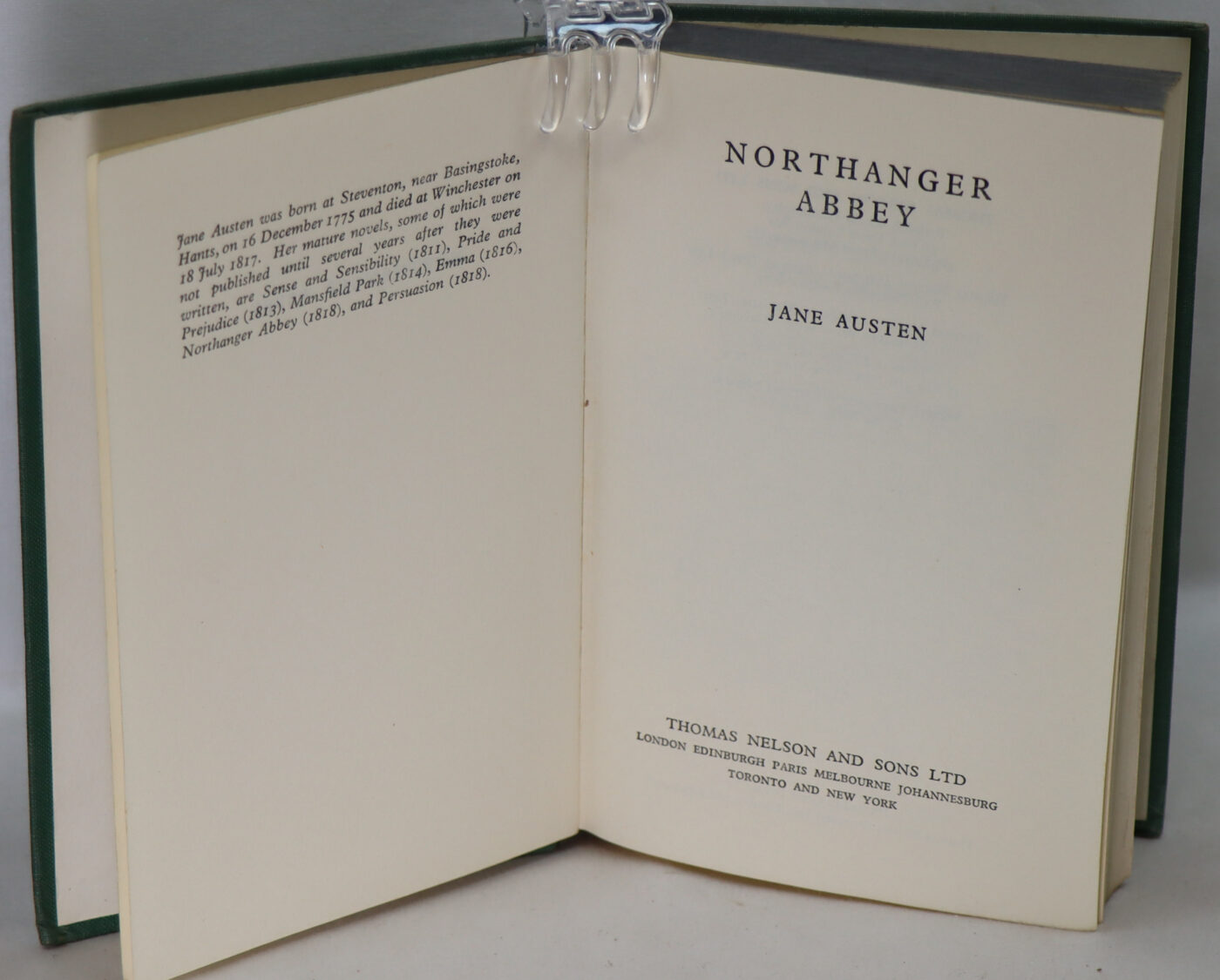

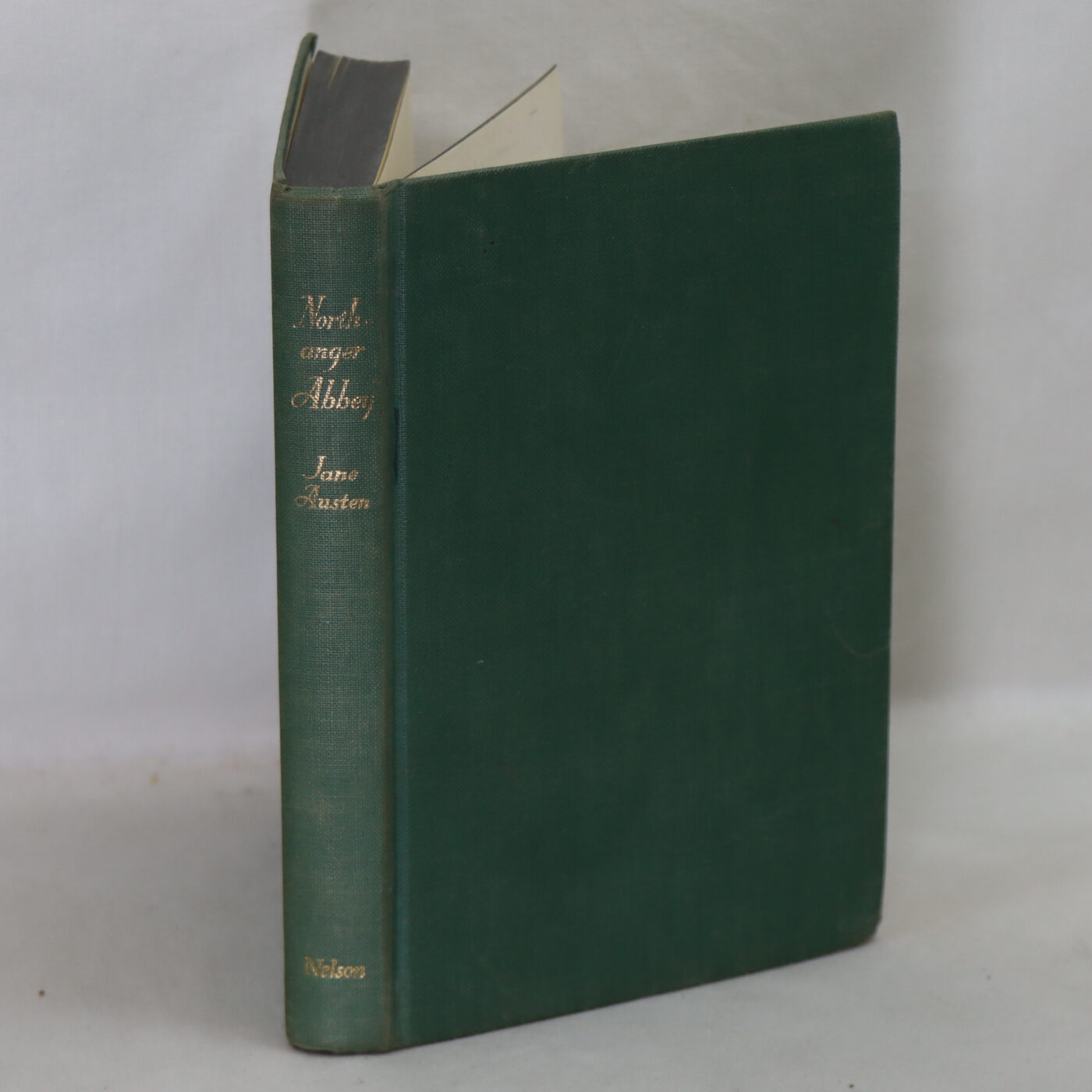

Northhanger Abbey.

By Jane Austen

Printed: Circa 1930

Publisher: Thomas Nelson & Sons. London

| Dimensions | 11 × 16 × 2 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 11 x 16 x 2

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Green cloth binding with gilt title on the spine

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

For conditions, please view our photographs. A nice clean copy from the library gathered by the famous Cambridge Don, computer scientist, food and wine connoisseur, Jack Arnold LANG.

Review: This is my favourite of all Austen’s works (although it comes very close to Pride & Prejudice and Sense & Sensibility)… In short, I’m an Austen fan, so perhaps this review isn’t as balanced as it should be…

However, I really do think there is an awful lot to like about this book. I’ve just read it for the fourth time for a course on Gothic literature I am doing and I have smiled pretty much all the way through it. It comes under the heading of “gothic parody” as Austen gently mocks the heroine and her perception of herself, her situating herself as an heroine, and the embarrassment which this leads to. What I don’t agree with is that it mocks the genre itself – as the hero Tilney states, he has gained a lot of pleasure from reading the “horrid” novels such as The Mysteries of Udolpho. What is being mocked is the heroine’s method of reading the books – she’s reading them as realistic, detailing events which are likely to occur, which, of course, they are not. It is something which the heroine, Catherine, comes to realise for herself: “Charming as were all Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, and charming even as were the works of all her imitators, it was not in them perhaps that human nature, at least in the midland counties of England, was to be looked for. Of the Alps and Pyrenees, with their pine forests and their vices, they might give a faithful delineation; and Italy, Switzerland, and the South of France, might be as fruitful in horrors as they were there represented. . . . But in the central part of England there was surely some security for the existence even of a wife not beloved, in the laws of the land, and the manners of the age. Murder was not tolerated, servants were not slaves, and neither poison nor sleeping potions to be procured, like rhubarb, from every druggist. Among the Alps and Pyrenees, perhaps, there were no mixed characters. There, such as were not spotless as an angel, might have the dispositions of a fiend. But in England it was not so . . . “(Austen, Northanger Abbey, vol. II, Chapter 10) At the end of the book, when Catherine is forcibly ejected from the Abbey, the story even takes quite a Gothic turn. General Tilney, may not have murdered his wife as Catherine initially suspected, but she suffers just as much at his hands with his precipitous ejection of her from his hospitality. Catherine herself can appreciate this: “Catherine, at any rate, heard enough to feel, that in suspecting General Tilney of either murdering or shutting up his wife, she had scarcely sinned against his character, or magnified his cruelty.” p. 243 There may be no wax figurines or wives imprisoned in the cloisters, but Catherine’s distress is very real. I adore this story – it is so easy to read; and if we are all guilty of seeing a little of ourselves in the heroines we read of, there is a lot of Catherine in us all. Flawed but charming, she is utterly delightful.

Jane Austen was born on December 16, 1775 at Steventon near Basingstoke, the seventh child of the rector of the parish. She lived with her family at Steventon until they moved to Bath when her father retired in 1801. After his death in 1805, she moved around with her mother; in 1809, they settled in Chawton, near Alton, Hampshire. Here she remained, except for a few visits to London, until in May 1817 she moved to Winchester to be near her doctor. There she died on July 18, 1817. As a girl Jane Austen wrote stories, including burlesques of popular romances. Her works were only published after much revision, four novels being published in her lifetime. These are Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814) and Emma(1816). Two other novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, were published posthumously in 1818 with a biographical notice by her brother, Henry Austen, the first formal announcement of her authorship. Persuasion was written in a race against failing health in 1815-16. She also left two earlier compositions, a short epistolary novel, Lady Susan, and an unfinished novel, The Watsons. At the time of her death, she was working on a new novel, Sanditon, a fragmentary draft of which survives.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend