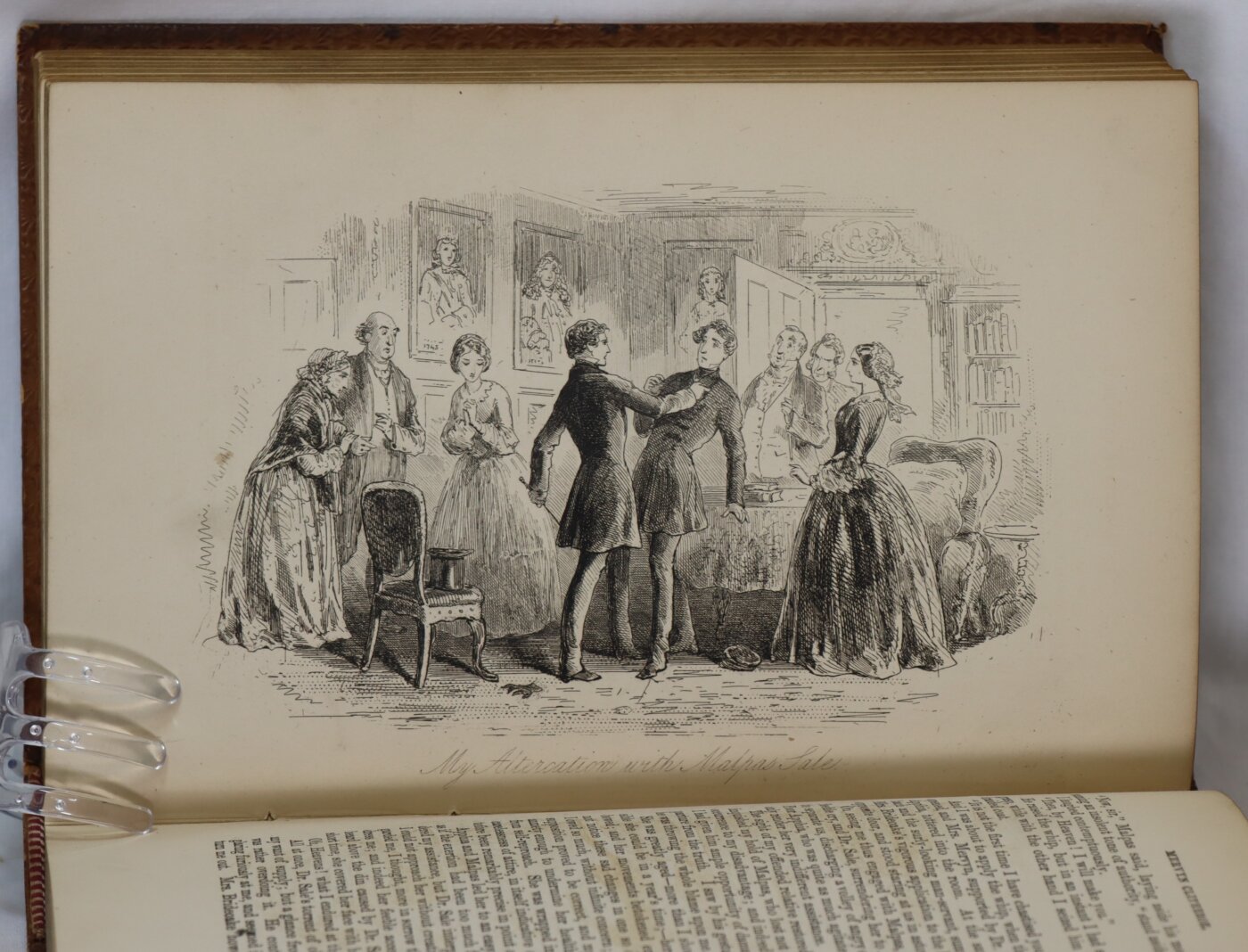

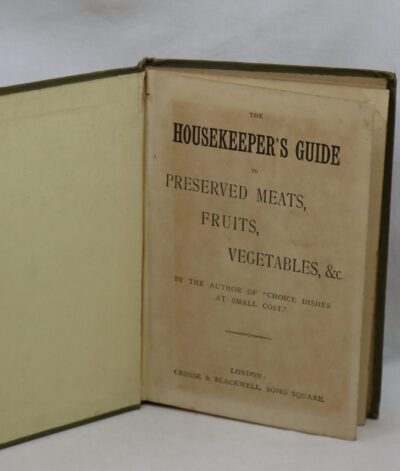

Mervyn Clitheroe.

By William Harrison Ainsworth

Printed: 1857-58

Publisher: George Routledge & Sons. London

| Dimensions | 15 × 22 × 4 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 15 x 22 x 4

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Item information

Description

Tan calf binding with gilt decoration, banding and title on the spine. All edges gilt.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

Mervyn Clitheroe: (PUBLISHED IN BOOK FORM 1857-58 formerly as part works from 1851): an early example of Phiz’s ‘dark plates’

Hablor K Browne (illustrator – Phiz). First Edition in book form. previously issued in parts. 8vo, pp. 372. View photographs: Illustrated with a frontispiece, engraved title-page and 22 plates by Hablot K. Browne. The first publisher of this (Chapman and Hall) suspended publication of the parts issue after no. 4 in 1852, the final parts were issued by Routledge starting in 1857, consequently the parts issue is very rare. A fine copy. A somewhat autobiographical novel set in Ainsworth’s home town of Manchester. Not a popular success. Both the frontispiece and the engraved title-vignette exhibit Phiz’s recent interest in developing atmospheric dark plates, and in early 1858 he had enough time on his hands to do the painstaking work since he had few other commissions. That said, this early example of Phiz’s dark plates makes this book highly collectable.

William Harrison Ainsworth (4 February 1805 – 3 January 1882) was an English historical novelist born at King Street in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in London he met the publisher John Ebers, at that time manager of the King’s Theatre, Haymarket. Ebers introduced Ainsworth to literary and dramatic circles, and to his daughter, who became Ainsworth’s wife.

The Ainsworth family moved to Smedley Lane, north of Manchester in Cheetham Hill, during 1811. They kept the old residence in addition to the new, but resided in the new home most of the time. The surrounding hilly country was covered in woods, which allowed Ainsworth and his brother to act out various stories. When not playing, Ainsworth was tutored by his uncle, William Harrison. In March 1817, he was enrolled at Manchester Grammar School, which was described in his novel Mervyn Clitheroe. The work emphasised that his classical education was of good quality but was reinforced with strict discipline and corporal punishment. Ainsworth was a strong student and was popular among his fellow students. His school days were mixed; his time within the school and with his family was calm even though there were struggles within the Manchester community, the Peterloo massacre taking place in 1819. Ainsworth was connected to the event because his uncles joined in protest at the incident, but Ainsworth was able to avoid most of the political after-effects. During the time, he was able to pursue his own literary interests and even created his own little theatre within the family home at King Street. Along with his friends and brother, he created and acted in many plays throughout 1820.

Ainsworth briefly tried the publishing business, but soon gave it up and devoted himself to journalism and literature. His first success as a writer came with Rookwood in 1834, which featured Dick Turpin as its leading character. A stream of 39 novels followed, the last of which appeared in 1881. Ainsworth died in Reigate on 3 January 1882, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Style and success: His first success as a writer came with Rookwood in 1834, which features Dick Turpin as its leading character. In 1839 he published another novel featuring a highwayman, Jack Sheppard. From 1840 to 1842 he edited Bentley’s Miscellany, from 1842 to 1853, Ainsworth’s Magazine and subsequently The New Monthly Magazine.

His Lancashire novels cover altogether 400 years and include The Lancashire Witches, 1848, Mervyn Clitheroe, 1857, and The Leaguer of Lathom. Jack Sheppard, Guy Fawkes, 1841, Old St Paul’s, 1841, Windsor Castle, 1843, and The Lancashire Witches are regarded as his most successful novels. He was very popular in his lifetime (in the early decades of the twentieth century King George V was a keen reader of his novels) and his books sold in large numbers, but his reputation has not lasted well. As John William Cousin argues, he depends for his effects on striking situations and powerful descriptions, but has little humour or power of delineating character. S. T. Joshi has characterized his output as an “appalling array of dreary and unreadable historical novels”. E. F. Bleiler has praised Windsor Castle as “the most enjoyable” of Ainsworth’s novels. Bleiler also stated “All in all, Ainsworth was not a great writer–his contemporaries included men and women who did things better–but he was a clean stylist and his work can be entertaining”. Historians have criticised the mingling of fact and fiction in his novels, noting that his romanticised treatment of Dick Turpin became rapidly accepted (popularly) as historical fact, while his novelisation of the 1612 Lancashire witch trials similarly distorted real events into a Gothic form.

Legacy: Ainsworth was largely forgotten by critics after his death. In 1911, S. M. Ellis commented: “It is certainly remarkable that, during the twenty-eight years which have elapsed since the death of William Harrison Ainsworth, no full record has been published of the exceptionally eventful career of one of the most picturesque personalities of the nineteenth century.” Ainsworth’s 1854 novel, The Flitch of Bacon, led to the modern revival of the flitch of bacon custom at Great Dunmow in Essex, whereby married couples who have lived together without strife are awarded a side of bacon. Ainsworth himself encouraged the revival by providing the prizes for the ceremony in 1855. The Dunmow Flitch Trials, in turn, were the basis for the 1952 film Made in Heaven starring Petula Clark. Ainsworth also appears as a character in the historical novel Shark Alley: The Memoirs of a Penny-a-Liner by Stephen Carver (2016), in which the Newgate Controversy is dramatized. Ainsworth is one of the protagonists of Zadie Smith’s 2023 novel The Fraud.

Hablot Knight Browne (10 July 1815 – 8 July 1882) was a British artist and illustrator. Well known by his pen name, Phiz, he illustrated books by Charles Dickens, Charles Lever, Augustus Septimus Mayhew and Harrison Ainsworth.

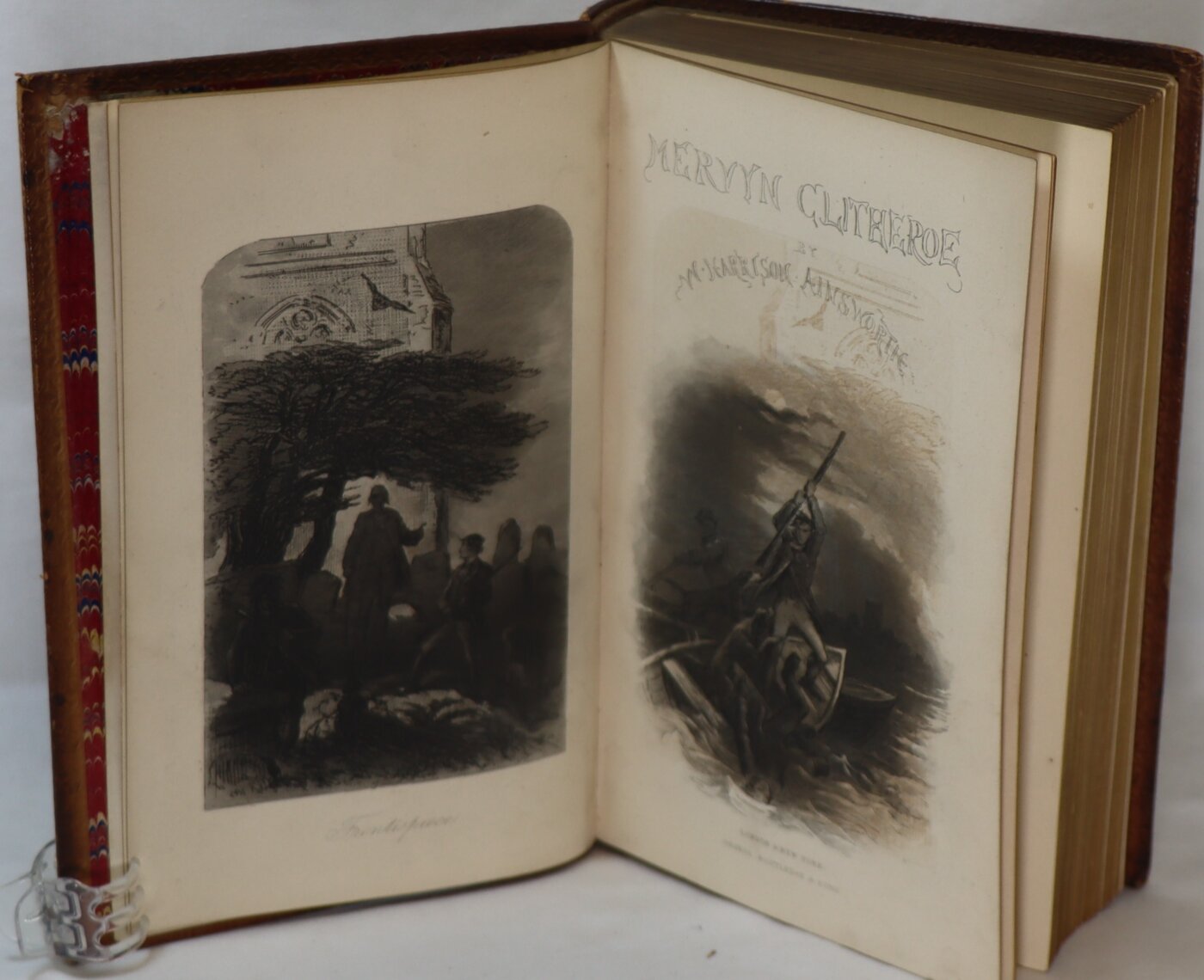

In the frontispiece to Mervyn Clitheroe, Phiz has admirably integrated all the atmospheric elements of the dramatic scene that spans several pages, recalling for readers at the close of the protracted serial run one of the most suspenseful moments at the conclusion of Book the First — and, moreover, a scene that sets up the remainder of the story. The illustration’s function, then, seems to have been to fuse the two parts of the novel as it recalls for readers in mid-1858 that part of the story published six years earlier. Phiz uses the frontispiece to foreground Simon Pownall’s ghost-impersonations, the novel’s Gothic atmosphere in the second book especially, and the plot device of the purloined will which defers Malpas Sales’ nemesis and Mervyn Clitheroe’s coming into his inheritance.

Beginning in 1847, Phiz had begun to experiment with creating dramatic effects through extreme chiaroscuro by etching ‘dark plates’, an effect he achieved by scoring the plate with closely set parallel lines. In such atmospheric illustrations as Phiz’s interpretation of the squalid Tom-all-alone’s in Chapter 46 of Bleak House(1853) the engraver uses intense shades of grey to describe twilight, evening, night, and gloomy interiors and invest them with suggestions of the moods ranging from the sinister, to the malignant, and the purely suspenseful.

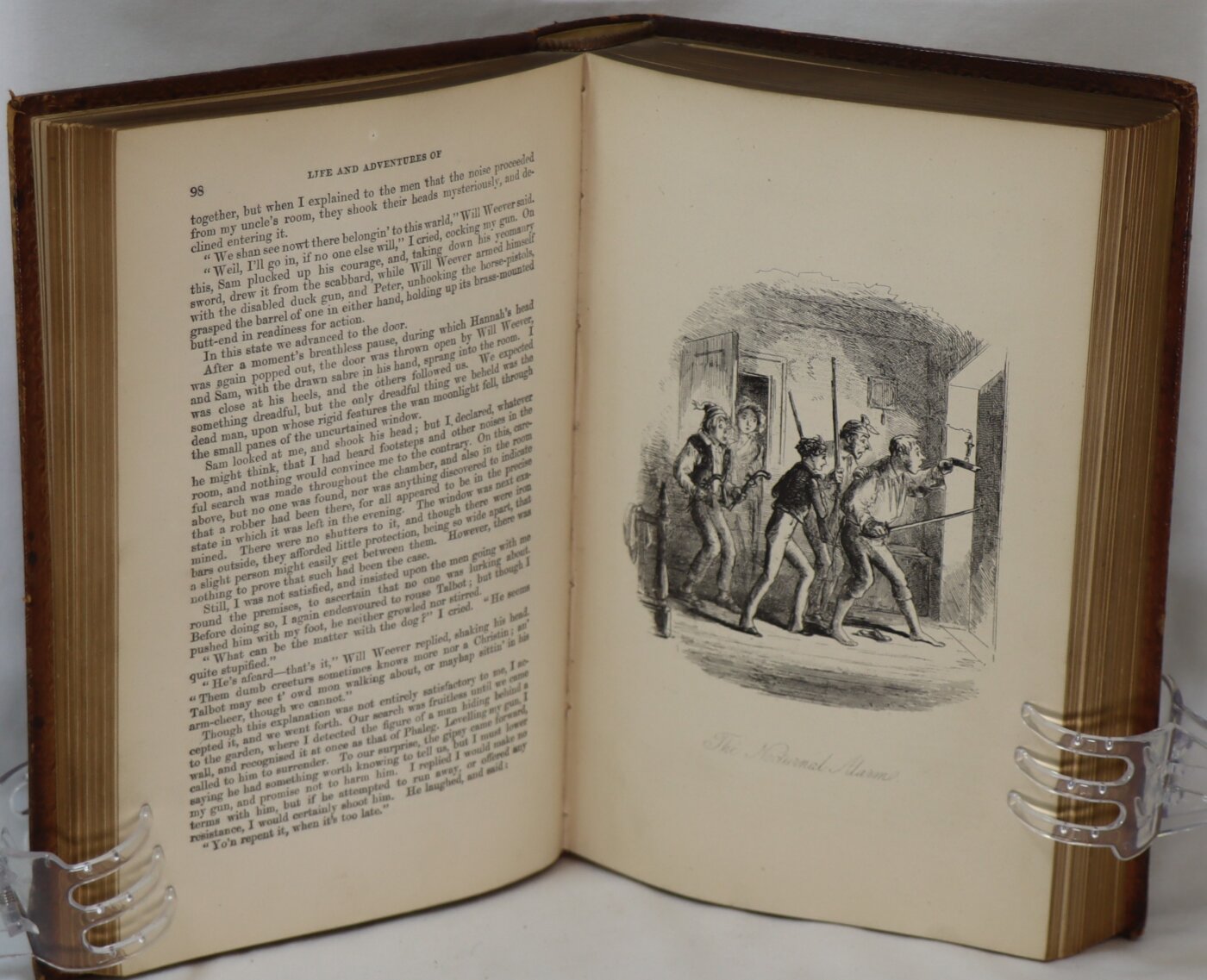

When, after an hiatus of five years and seven months, Phiz returned to the project with new publishers, he had become enamored of the so-called “dark plate,” an atmospheric treatment upon which he had relied heavily in the monthly illustrations for Bleak House (1853). Consequently, he employed this engraving technique for a significant number of the illustrations in Books Two and Three (December 1857 through June 1858), including the frontispiece and title-page vignette. Of the twenty-four steel-engravings for Mervyn Clitheroe, none of the eight are dark plates in Book the First (December 1851 through March 1852), but twelve of the sixteen plates for the second and third books demonstrate Phiz’s mastery of this engraving technique. Aside from the frontispiece, Phiz employed the technique to some extent in the following atmospheric illustrations for Books Two and Three:

- 2.Vignette Title (Part 11-12, 1858 June)

- 12.The Duel on Crabtree-Green (Part 5, 1857 Dec.)

- 13.I receive Sad Intelligence from Ned Culcheth (Part 6, 1858 Jan.)

- 14.The Mysterious Bell-ringing at Owlarton Grange (Part 6, 1858 Jan.)

- 15.The Legend of Owlarton Grange (Part 7, 1858 Feb.)

- 16.The Adventure of the Haunted Chamber (Part 7, 1858 Feb.)

- 17.The Stranger at the Grave (Part 8, 1858 March)

- 18.The Conjurors Interrupted (Part 8, 1858 March)

- 19.I find Pownall in Conference with the Gipsies (Part 9, 1858 April)

- 21.The Deed of Settlement (Part 10, 1858 May)

- 22.The Meeting in Delamere Forest (Part 10, 1858 May)

This pair of June 1858 illustrations, the frontispiece and the engraved vignette-title, Phiz may have created as early as March 1858, anticipating the conclusion of the serial run in June, if Ainsworth had explained to him the significance of the stranger in the churchyard. Over the period in which the project lay dormant Phiz had undertaken several significant commissions for other writers, notably Dickens’s Bleak House in 1853 and Little Dorrit in 1855-56. However, two different influences are particularly evident in Phiz’s illustrations for the protracted serialisation of Mervyn Clitheroe: his line drawings for David Copperfield (1849-50) in the illustrations for Book the First, and the dark plates from Bleak House in the second and third books. Both the frontispiece and the engraved title-vignette exhibit Phiz’s recent interest in developing atmospheric dark plates, and in early 1858 he had enough time on his hands to do the painstaking work since he had few other commissions.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend