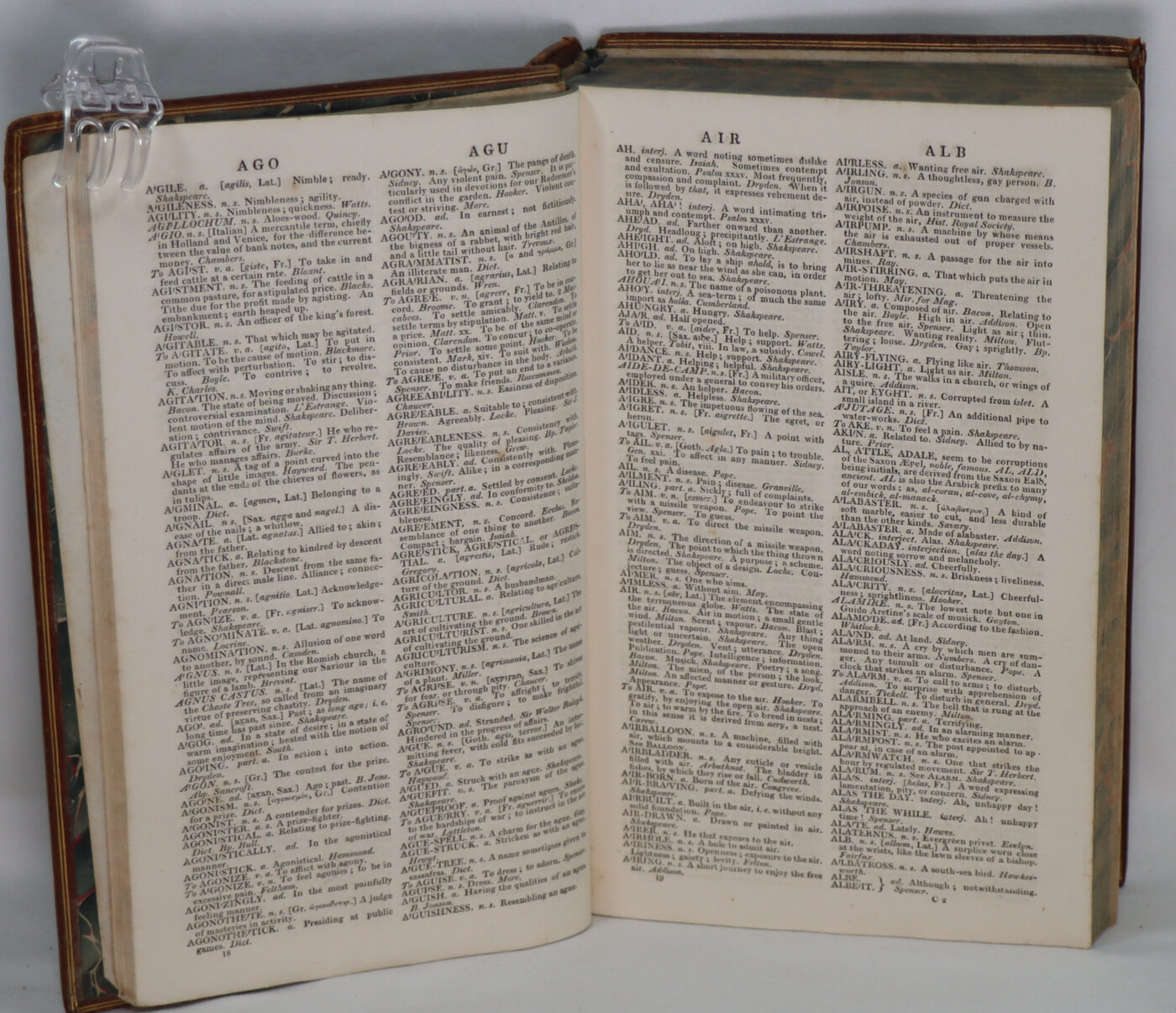

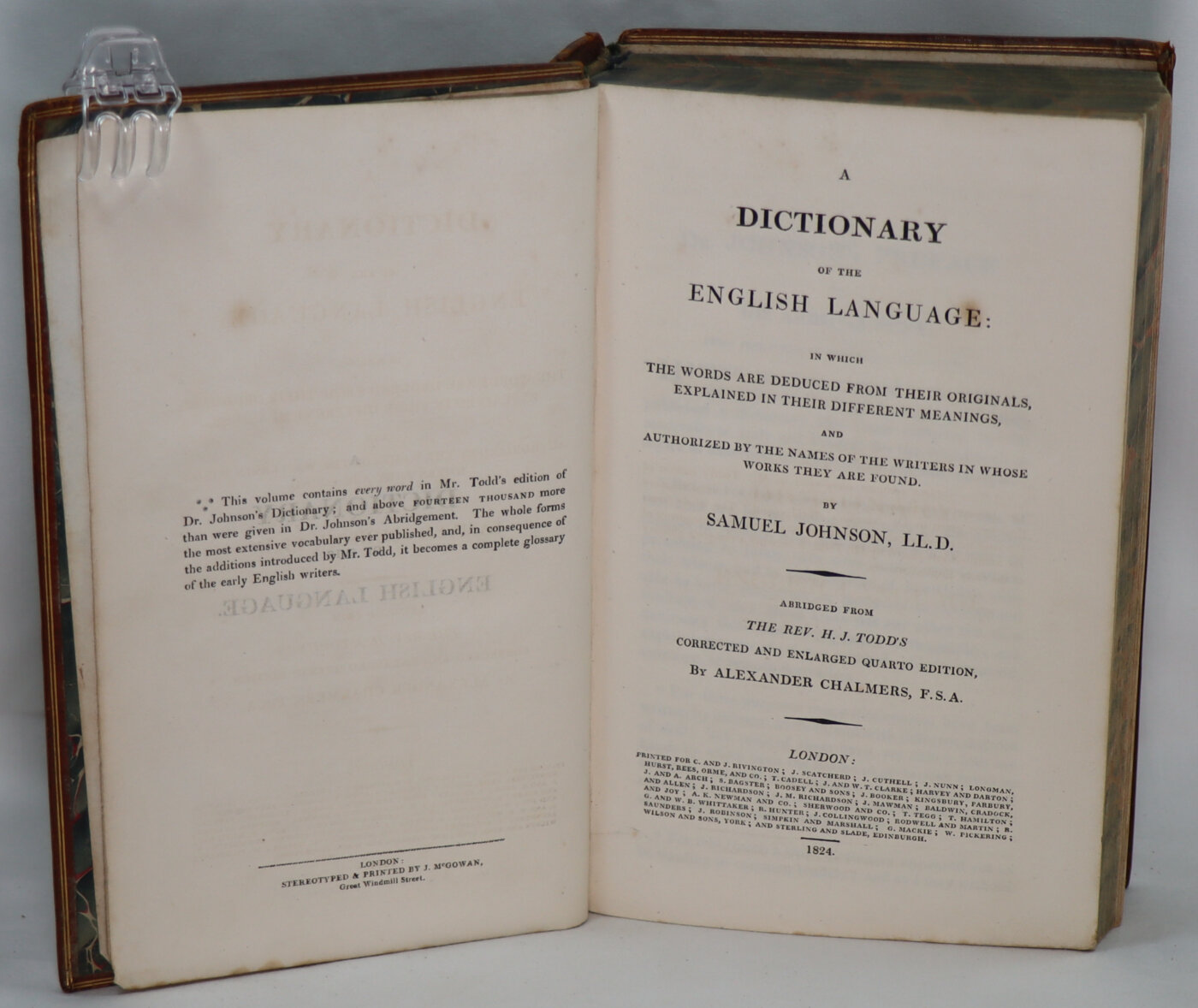

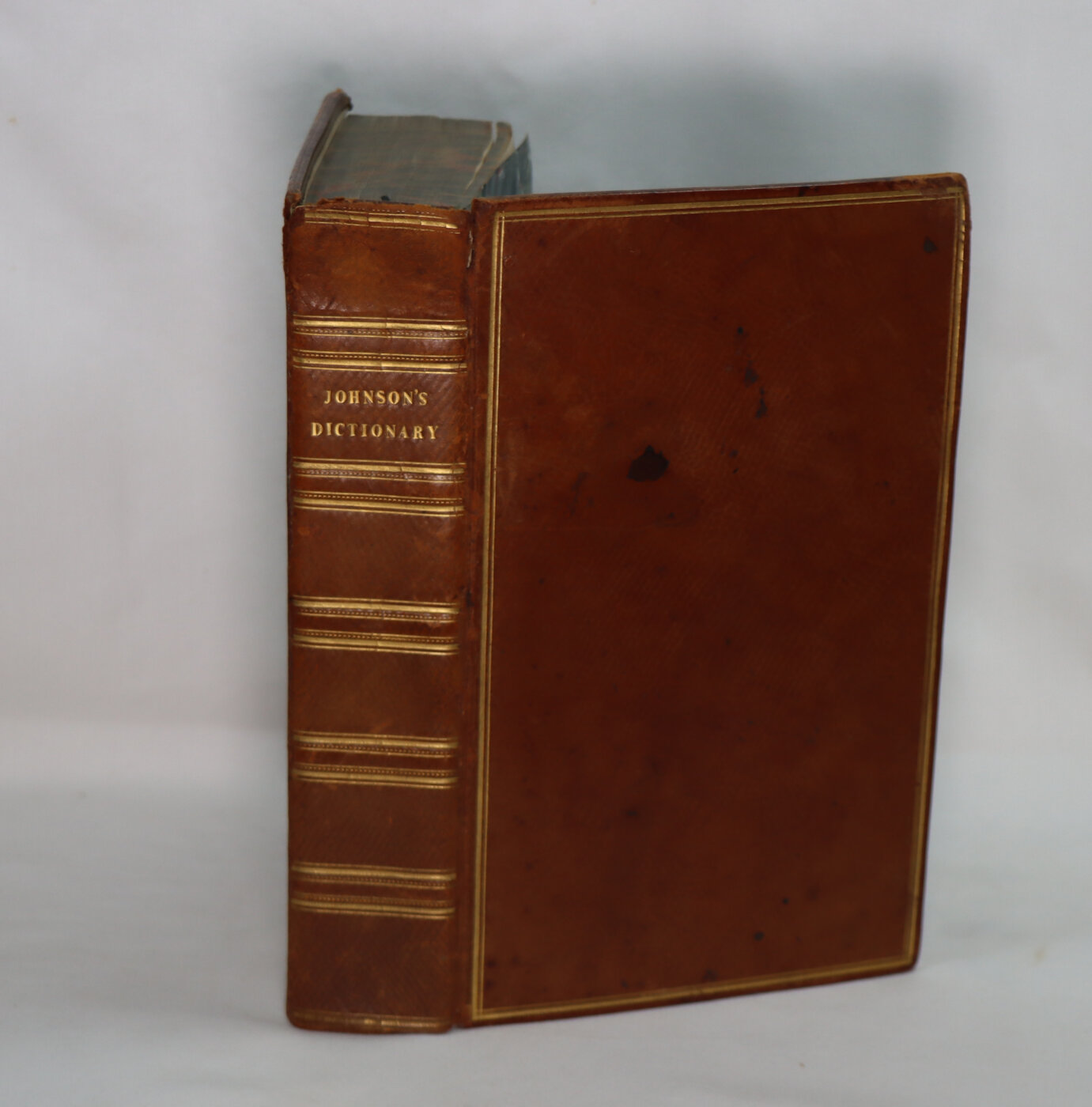

Johnson's Dictionary.

By Samuel Johnson

Printed: 1824

Publisher: C & J Rivington. London

| Dimensions | 15 × 23 × 5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 15 x 23 x 5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Your items

Item information

Description

Tan calf binding with gilt banding and title on the spine.

- F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

- Note: This book carries the £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list.

A good solid book, not exceptional but worth a place in any library.

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 [OS 7 September] – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography calls him “arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history”.

Born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, he attended Pembroke College, Oxford, until lack of funds forced him to leave. After working as a teacher, he moved to London and began writing for The Gentleman’s Magazine. Early works include Life of Mr Richard Savage, the poems London and The Vanity of Human Wishes and the play Irene. After nine years’ effort, Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language appeared in 1755, and was acclaimed as “one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship”. Later work included essays, an annotated The Plays of William Shakespeare, and the apologue The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia. In 1763 he befriended James Boswell, with whom he travelled to Scotland, as Johnson described in A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland. Near the end of his life came a massive, influential Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Dr Johnson was a devout Anglican, and a committed Tory. Tall and robust, he displayed gestures and tics that disconcerted some on meeting him. Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, along with other biographies, documented Johnson’s behavior and mannerisms in such detail that they have informed the posthumous diagnosis of Tourette syndrome, a condition not defined or diagnosed in the 18th century. After several illnesses, he died on the evening of 13 December 1784 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

In his later life Johnson became a celebrity, and following his death he was increasingly seen to have had a lasting effect on literary criticism, even being claimed to be the one truly great critic of English literature. A prevailing mode of literary theory in the 20th century drew from his views, and he had a lasting impact on biography. Johnson’s Dictionary had far-reaching effects on Modern English, and was pre-eminent until the arrival of the Oxford English Dictionary 150 years later. Boswell’s Life was selected by Johnson biographer Walter Jackson Bate as “the most famous single work of biographical art in the whole of literature”.

In 1746, a group of publishers approached Johnson with the idea of creating an authoritative dictionary of the English language. A contract with William Strahan and associates, worth 1,500 guineas, was signed on the morning of 18 June 1746. Johnson claimed that he could finish the project in three years. In comparison, the Académie Française had 40 scholars spending 40 years to complete their dictionary, which prompted Johnson to claim, “This is the proportion. Let me see; forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman.” Although he did not succeed in completing the work in three years, he did manage to finish it in eight. Some criticised the dictionary, including the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, who described Johnson as “a wretched etymologist,” but according to Bate, the Dictionary “easily ranks as one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship, and probably the greatest ever performed by one individual who laboured under anything like the disadvantages in a comparable length of time.”

Johnson’s constant work on the Dictionary disrupted his and Tetty’s living conditions. He had to employ a number of assistants for the copying and mechanical work, which filled the house with incessant noise and clutter. He was always busy, and kept hundreds of books around him. John Hawkins described the scene: “The books he used for this purpose were what he had in his own collection, a copious but a miserably ragged one, and all such as he could borrow; which latter, if ever they came back to those that lent them, were so defaced as to be scarce worth owning.” Johnson’s process included underlining words in the numerous books he wanted to include in his Dictionary. The assistants would copy out the underlined sentences on individual paper slips, which would later be alphabetized and accompanied with examples. Johnson was also distracted by Tetty’s poor health as she began to show signs of a terminal illness. To accommodate both his wife and his work, he moved to 17 Gough Square near his printer, William Strahan.

In preparation, Johnson had written a Plan for the Dictionary. Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, was the patron of the Plan, to Johnson’s displeasure. Seven years after first meeting Johnson to go over the work, Chesterfield wrote two anonymous essays in The World recommending the Dictionary. He complained that the English language lacked structure and argued in support of the dictionary. Johnson did not like the tone of the essays, and he felt that Chesterfield had not fulfilled his obligations as the work’s patron. In a letter to Chesterfield, Johnson expressed this view and harshly criticised Chesterfield, saying “Is not a patron, my lord, one who looks with unconcern on a man struggling for life in the water, and when he has reached ground, encumbers him with help? The notice which you have been pleased to take of my labours, had it been early, had been kind: but it has been delayed till I am indifferent and cannot enjoy it; till I am solitary and cannot impart it; till I am known and do not want it.” Chesterfield, impressed by the language, kept the letter displayed on a table for anyone to read.

The Dictionary was finally published in April 1755, with the title page noting that the University of Oxford had awarded Johnson a Master of Arts degree in anticipation of the work. The dictionary as published was a large book. Its pages were nearly 18 inches (46 cm) tall, and the book was 20 inches (51 cm) wide when opened; it contained 42,773 entries, to which only a few more were added in subsequent editions, and it sold for the extravagant price of £4 10s, perhaps the rough equivalent of £350 today.

An important innovation in English lexicography was to illustrate the meanings of his words by literary quotation, of which there were approximately 114,000. The authors most frequently cited include William Shakespeare, John Milton and John Dryden. It was years before Johnson’s Dictionary, as it came to be known, turned a profit. Authors’ royalties were unknown at the time, and Johnson, once his contract to deliver the book was fulfilled, received no further money from its sale. Years later, many of its quotations would be repeated by various editions of the Webster’s Dictionary and the New English Dictionary.

Johnson’s dictionary was not the first, nor was it unique. Other dictionaries, such as Nathan Bailey’s Dictionarium Britannicum, included more words, and in the 150 years preceding Johnson’s dictionary about twenty other general-purpose monolingual “English” dictionaries had been produced. However, there was open dissatisfaction with the dictionaries of the period. In 1741, David Hume claimed: “The Elegance and Propriety of Stile have been very much neglected among us. We have no Dictionary of our Language, and scarce a tolerable Grammar.” Johnson’s Dictionary offers insights into the 18th century and “a faithful record of the language people used”. It is more than a reference book; it is a work of literature. It was the most commonly used and imitated for the 150 years between its first publication and the completion of the Oxford English Dictionary in 1928.

Johnson also wrote numerous essays, sermons, and poems during his years working on the dictionary. In 1750, he decided to produce a series of essays under the title The Rambler that were to be published every Tuesday and Saturday and sell for twopence each. During this time, Johnson published no fewer than 208 essays, each around 1,200–1,500 words long. Explaining the title years later, he told his friend and portraitist Joshua Reynolds: “I was at a loss how to name it. I sat down at night upon my bedside, and resolved that I would not go to sleep till I had fixed its title. The Rambler seemed the best that occurred, and I took it.”These essays, often on moral and religious topics, tended to be more grave than the title of the series would suggest; his first comments in The Rambler were to ask “that in this undertaking thy Holy Spirit may not be withheld from me, but that I may promote thy glory, and the salvation of myself and others.” The popularity of The Rambler took off once the issues were collected in a volume; they were reprinted nine times during Johnson’s life. Writer and printer Samuel Richardson, enjoying the essays greatly, questioned the publisher as to who wrote the works; only he and a few of Johnson’s friends were told of Johnson’s authorship. One friend, the novelist Charlotte Lennox, includes a defense of The Rambler in her novel The Female Quixote (1752). In particular, the character Mr. Glanville says, “you may sit in Judgment upon the Productions of a Young, a Richardson, or a Johnson. Rail with premeditated Malice at the Rambler; and for the want of Faults, turn even its inimitable Beauties into Ridicule.” (Book VI, Chapter XI) Later, the novel describes Johnson as “the greatest Genius in the present Age.”

His necessary attendance while his play was in rehearsal, and during its performance, brought him acquainted with many of the performers of both sexes, which produced a more favourable opinion of their profession than he had harshly expressed in his Life of Savage. With some of them he kept up an acquaintance as long as he and they lived, and was ever ready to shew them acts of kindness. He for a considerable time used to frequent the Green Room, and seemed to take delight in dissipating his gloom, by mixing in the sprightly chit-chat of the motley circle then to be found there. Mr. David Hume related to me from Mr. Garrick, that Johnson at last denied himself this amusement, from considerations of rigid virtue; saying, ‘I’ll come no more behind your scenes, David; for the silk stockings and white bosoms of your actresses excite my amorous propensities.

Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson

Not all of his work was confined to The Rambler. His most highly regarded poem, The Vanity of Human Wishes, was written with such “extraordinary speed” that Boswell claimed Johnson “might have been perpetually a poet”. The poem is an imitation of Juvenal’s Satire X and claims that “the antidote to vain human wishes is non-vain spiritual wishes”.

In particular, Johnson emphasises “the helpless vulnerability of the individual before the social context” and the “inevitable self-deception by which human beings are led astray”. The poem was critically celebrated but it failed to become popular, and sold fewer copies than London. In 1749, Garrick made good on his promise that he would produce Irene, but its title was altered to Mahomet and Irene to make it “fit for the stage.”[ Irene, which was written in blank verse, was received rather poorly with a friend of Boswell’s commenting the play to be “as frigid as the regions of Nova Zembla: now and then you felt a little heat like what is produced by touching ice.” The show eventually ran for nine nights.

Tetty Johnson was ill during most of her time in London, and in 1752 she decided to return to the countryside while Johnson was busy working on his Dictionary. She died on 17 March 1752, and, at word of her death, Johnson wrote a letter to his old friend Taylor, which according to Taylor “expressed grief in the strongest manner he had ever read”. Johnson wrote a sermon in her honour, to be read at her funeral, but Taylor refused to read it, for reasons which are unknown. This only exacerbated Johnson’s feelings of loss and despair. Consequently, John Hawkesworth had to organise the funeral. Johnson felt guilty about the poverty in which he believed he had forced Tetty to live, and blamed himself for neglecting her. He became outwardly discontented, and his diary was filled with prayers and laments over her death which continued until his own. She was his primary motivation, and her death hindered his ability to complete his work.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

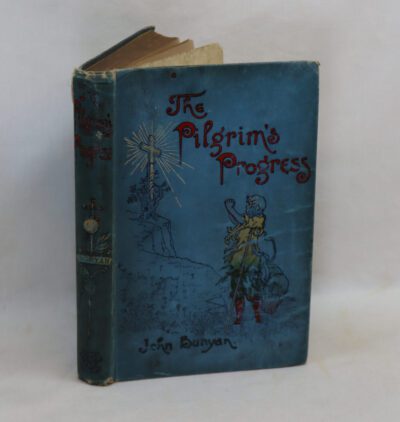

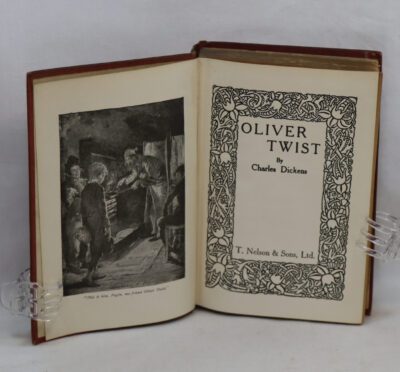

Related products

Share this Page with a friend