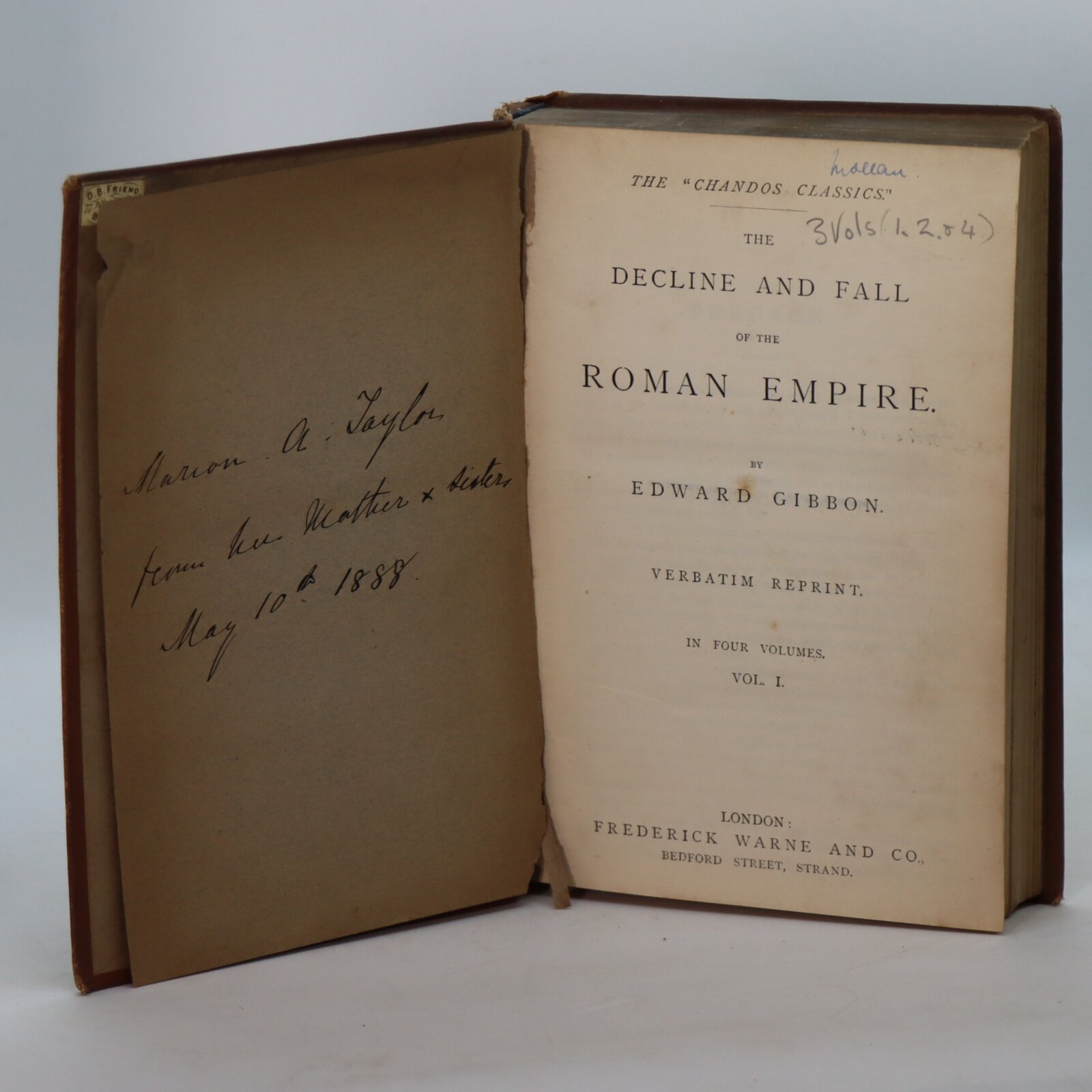

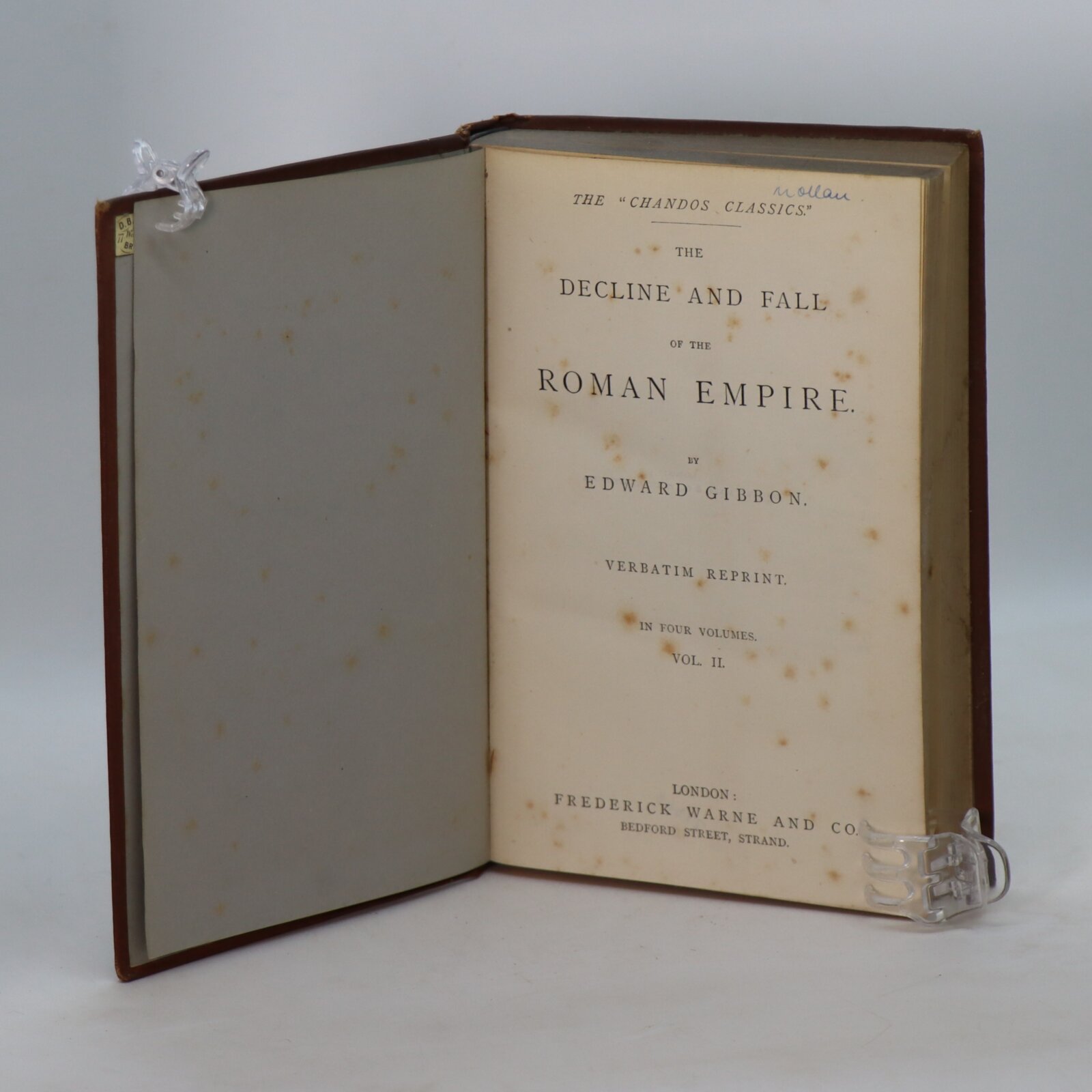

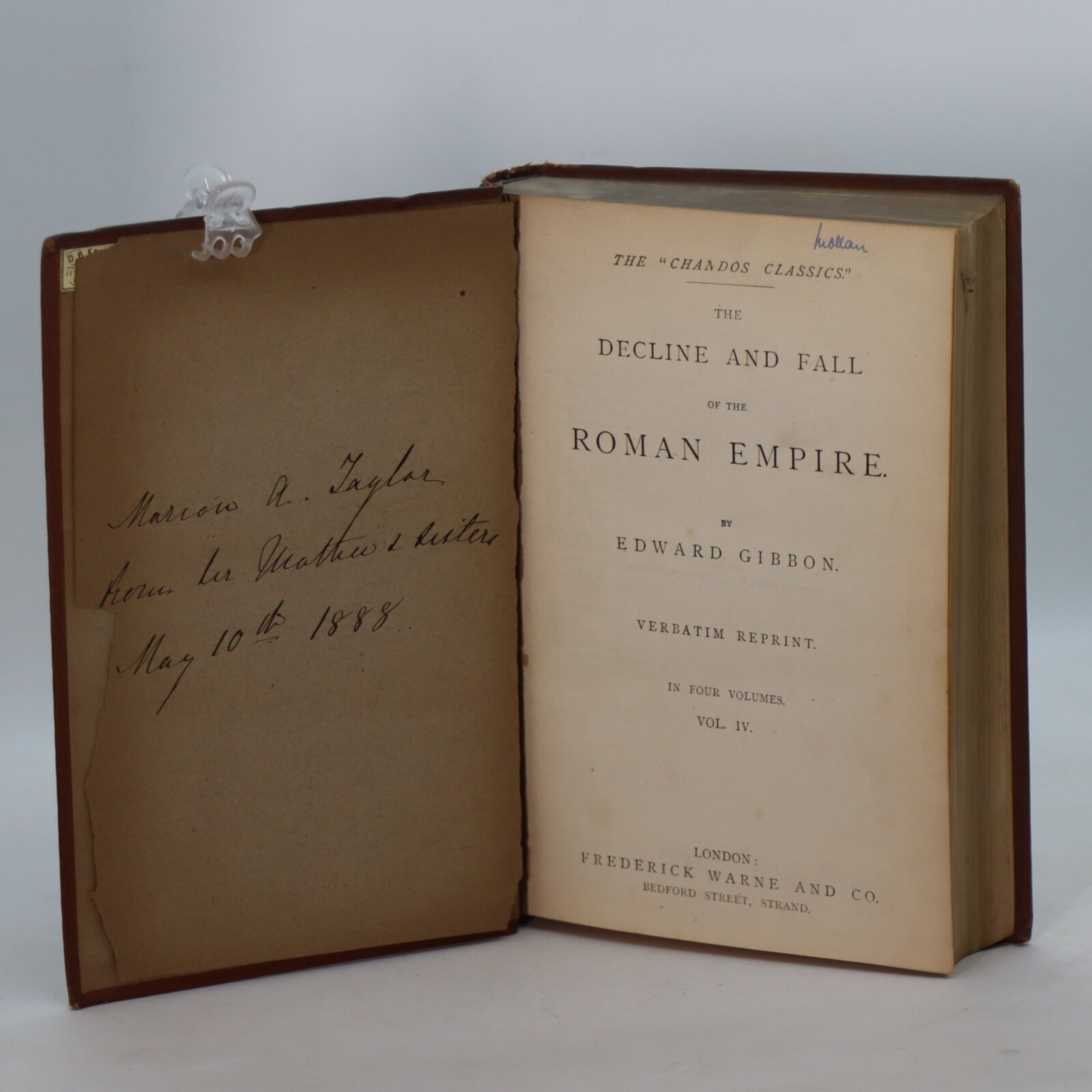

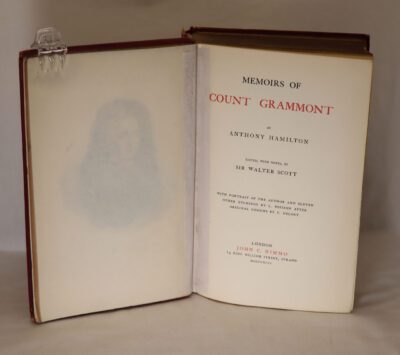

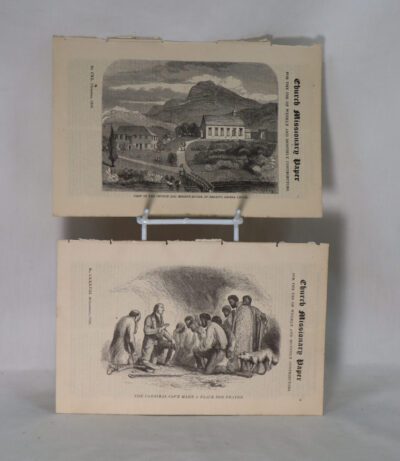

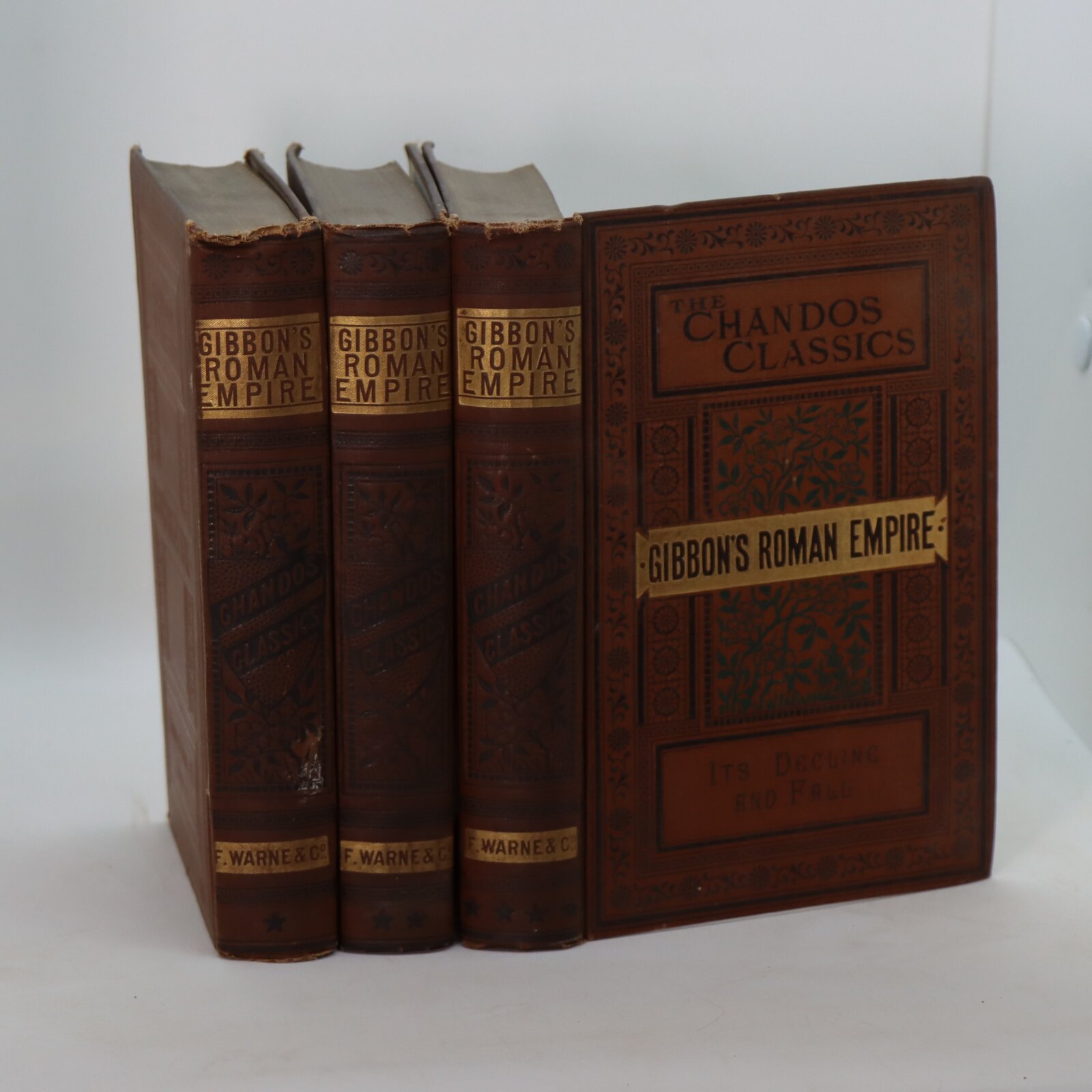

Gibbon's Roman Empire. It's Decline and Fall. Volumes I, II & IV.

By Edward Gibbon

Printed: Circa 1890

Publisher: Frederick Warne & Co. London

Edition: Verbatim reprint.

| Dimensions | 13 × 19 × 3.5 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 13 x 19 x 3.5

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Your items

Item information

Description

Brown cloth binding. Black embossed “Chandos Classics” floral design on front and spine with gilt title on front board and spine. Gilt Whitby arms on front board.

Dimensions are for one volume.

It is the intent of F.B.A. to provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this book offered so to almost stimulate your feel and touch on the book. If requested, more traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Three nice books but giving but an impartial presentation

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is a six-volume work by the English historian Edward Gibbon. It traces Western civilization (as well as the Islamic and Mongolian conquests) from the height of the Roman Empire to the fall of Byzantium in the fifteenth century. Volume I was published in 1776 and went through six printings. Volumes II and III were published in 1781; volumes IV, V, and VI in 1788–1789. The six volumes cover the history, from 98 to 1590, of the Roman Empire, the history of early Christianity and then of the Roman State Church, and the history of Europe, and discusses the decline of the Roman Empire among other things.

Edward Gibbon FRS (8 May 1737 – 16 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and Member of Parliament. His most important work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is known for the quality and irony of its prose, its use of primary sources, and its polemical criticism of organised religion.

Edward Gibbon’s central thesis in his explanation of how the Roman Empire fell, that it was due to embracing Christianity, is not widely accepted by scholars today. Gibbon argued that with the empire’s new Christian character, large sums of wealth that would have otherwise been used in the secular affairs in promoting the state were transferred to promoting the activities of the Church. However, the pre-Christian empire also spent large financial sums on religious affairs, and it is unclear whether or not the change of religion increased the amount of resources the empire spent on religion. Gibbon further argued that new attitudes in Christianity caused many Christians of wealth to renounce their lifestyles and enter a monastic lifestyle, and so stop participating in the support of the empire. However, while many Christians of wealth did become monastics, this paled in comparison to the participants in the imperial bureaucracy. Although Gibbon further pointed out the importance Christianity placed on peace caused a decline in the number of people serving the military, the decline was so small as to be negligible for the army’s effectiveness.

Gibbon’s work has been criticised for its scathing view of Christianity as laid down in chapters XV and XVI, a situation which resulted in the banning of the book in several countries. Gibbon’s alleged crime was disrespecting, and none too lightly, the character of sacred Christian doctrine, by “treat[ing] the Christian church as a phenomenon of general history, not a special case admitting supernatural explanations and disallowing criticism of its adherents”. More specifically, the chapters excoriated the church for “supplanting in an unnecessarily destructive way the great culture that preceded it” and for “the outrage of [practising] religious intolerance and warfare”.

Gibbon, in letters to Holroyd and others, expected some type of church-inspired backlash, but the harshness of the ensuing torrents exceeded anything he or his friends had anticipated. Contemporary detractors such as Joseph Priestley and Richard Watson stoked the nascent fire, but the most severe of these attacks was an “acrimonious” piece by the young cleric, Henry Edwards Davis. Gibbon subsequently published his Vindication in 1779, in which he categorically denied Davis’ “criminal accusations”, branding him a purveyor of “servile plagiarism.” Davis followed Gibbon’s Vindication with yet another reply (1779).

Gibbon’s apparent antagonism to Christian doctrine spilled over into the Jewish faith, leading to charges of anti-Semitism. For example, he wrote:

From the reign of Nero to that of Antoninus Pius, the Jews discovered a fierce impatience of the dominion of Rome, which repeatedly broke out in the most furious massacres and insurrections. Humanity is shocked at the recital of the horrid cruelties which they committed in the cities of Egypt, of Cyprus, and of Cyrene, where they dwelt in treacherous friendship with the unsuspecting natives; and we are tempted to applaud the severe retaliation which was exercised by the arms of legions against a race of fanatics, whose dire and credulous superstition seemed to render them the implacable enemies not only of the Roman government, but also of humankind.

Influence

Gibbon is considered to be a son of the Enlightenment, and this is reflected in his famous verdict on the history of the Middle Ages: “I have described the triumph of barbarism and religion.” However, politically, he aligned himself with the conservative Edmund Burke’s rejection of the radical egalitarian movements of the time as well as with Burke’s dismissal of overly rationalistic applications of the “rights of man”.

Gibbon’s work has been praised for its style, his piquant epigrams and its effective irony. Winston Churchill memorably noted in My Early Life, “I set out upon…Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire [and] was immediately dominated both by the story and the style. …I devoured Gibbon. I rode triumphantly through it from end to end and enjoyed it all.” Churchill modelled much of his own literary style on Gibbon’s. Like Gibbon, he dedicated himself to producing a “vivid historical narrative, ranging widely over period and place and enriched by analysis and reflection.”

Unusually for the 18th century, Gibbon was never content with second-hand accounts when the primary sources were accessible (though most of these were drawn from well-known printed editions). “I have always endeavoured,” he says, “to draw from the fountain-head; that my curiosity, as well as a sense of duty, has always urged me to study the originals; and that, if they have sometimes eluded my search, I have carefully marked the secondary evidence, on whose faith a passage or a fact were reduced to depend.” In this insistence upon the importance of primary sources, Gibbon is considered by many to be one of the first modern historians:

In accuracy, thoroughness, lucidity, and comprehensive grasp of a vast subject, the ‘History’ is unsurpassable. It is the one English history which may be regarded as definitive…Whatever its shortcomings the book is artistically imposing as well as historically unimpeachable as a vast panorama of a great period.

The subject of Gibbon’s writing, as well as his ideas and style, have influenced other writers. Besides his influence on Churchill, Gibbon was also a model for Isaac Asimov in his writing of The Foundation Trilogy, which he said involved “a little bit of cribbin’ from the works of Edward Gibbon”.

Evelyn Waugh admired Gibbon’s style, but not his secular viewpoint. In Waugh’s 1950 novel Helena, the early Christian author Lactantius worried about the possibility of “‘a false historian, with the mind of Cicero or Tacitus and the soul of an animal,’ and he nodded towards the gibbon who fretted his golden chain and chattered for fruit.”

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend