Andrew Marvel and his Friends.

By Marie Hall

Printed: 1895

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton. London

Edition: Eighth edition

| Dimensions | 14 × 20 × 4 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 14 x 20 x 4

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

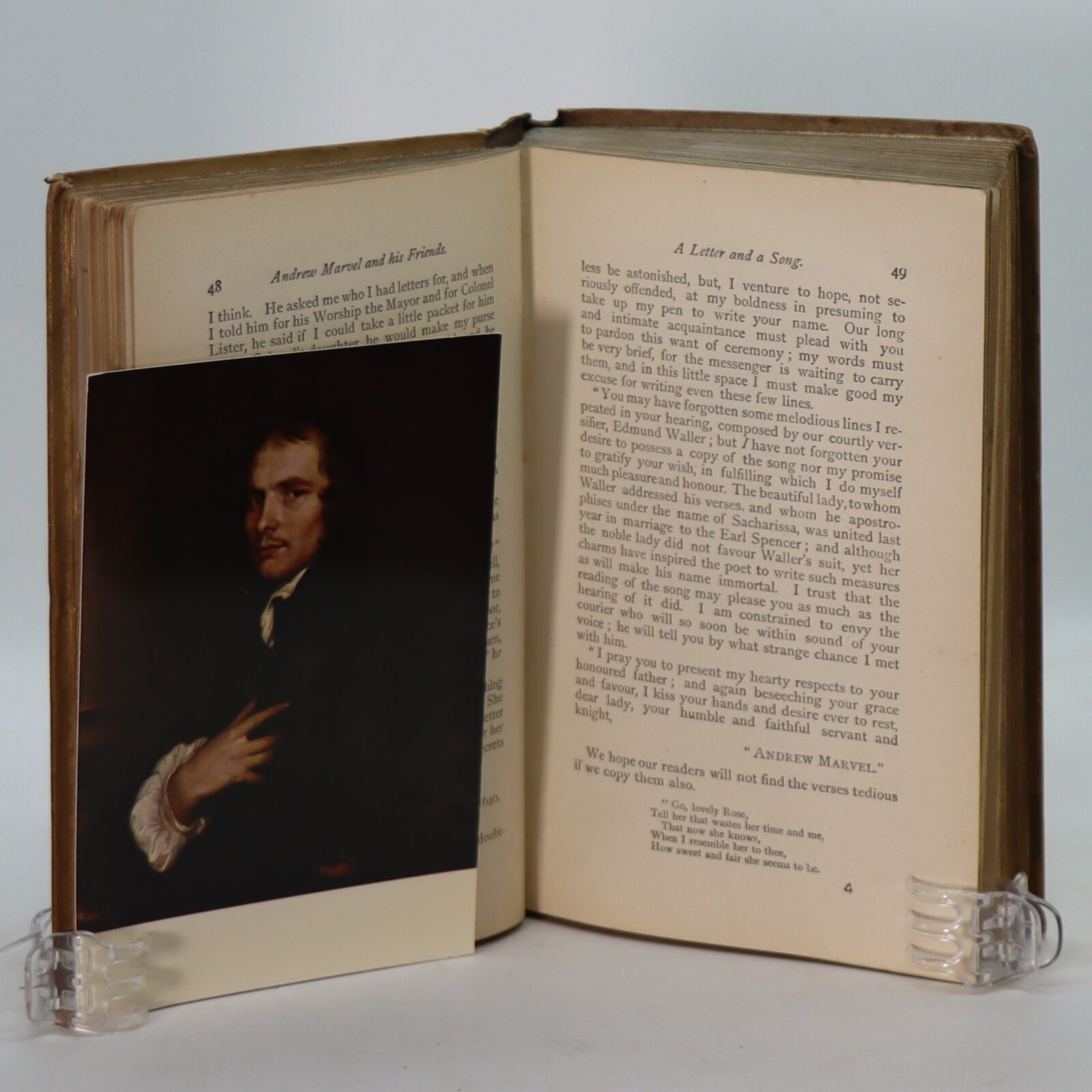

Tan cloth binding with Britainia, sailing ship and white ensign on the front board. Ship, title and british flag on the spine. Incuded a postcard of Andrew Mavel by Adrian Hanneman in Ferens Art Gallery, Hull. https://www.f-b-a.com/product/notices-of-the-town-and-port-of-hull/

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feel and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

Written by Marie Sibree Hall as a patriotic children’s book. Marie Sibree Hall was a native of Hull though she later lived around Bradford where she wrote many books.

The first Siege of Hull marked a major escalation in the conflict between King Charles I and Parliament during the build-up to the First English Civil War. Charles sought to secure the large arsenal held in Kingston upon Hull, East Riding of Yorkshire. He first approached the town in late April 1642, but was rebuffed by the town’s Parliamentarian governor, Sir John Hotham. Charles retreated to York, but in July he received news that Hotham might be willing to hand over the town if the Royalists approached with a large enough force that Hotham could surrender with his honour intact.

Charles marched towards the town with an army of 4,000 men. In the meantime, Hull had been reinforced by sea, and Parliament had sent Sir John Meldrum to command the town’s garrison, as they were concerned about Hotham’s loyalty. Hotham once again rejected the King’s demands to enter the town, and a largely ineffective siege was established by the Royalists, commanded by the Earl of Lindsey as the King had returned to York. Meldrum led a series of successful sallies from the town, and after a particularly effective one on 27 July, which destroyed a Royalist magazine to the west of the town, Lindsey lifted the siege and withdrew the King’s forces to York.

In the 17th century, Kingston upon Hull, or Hull, was the second largest town in Yorkshire; with a population of 7,000, only the northern capital of York was bigger. Access to the North Sea meant it was the primary export point for manufactured goods produced in Northern England; while its position at the confluence of the Hull and Humber rivers also made it the centre of an inland trade route.

In his military history of Yorkshire, David Cooke called it “a very important town”, while the Victoria County History described it as “strategically important”. Its arms magazine in Lowgate was the second largest in England after the Tower of London; in 1642, it contained 120 artillery pieces, 7,000 barrels of powder, and weapons for 16,000 to 20,000 men.

The town’s position made it naturally very defensible. It had been fortified in the fourteenth century, and these defences were enhanced over time. By the 1630s, Hull was completely enclosed by walls; on the west bank of the River Hull, on which the town itself sat, medieval walls fronted by a ditch and interspersed with 25 towers were located on all but the river-side of the town. On the east bank, a three-metre-thick (9.8 ft) curtain wall featuring three blockhouses had been erected during the reign of Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547).

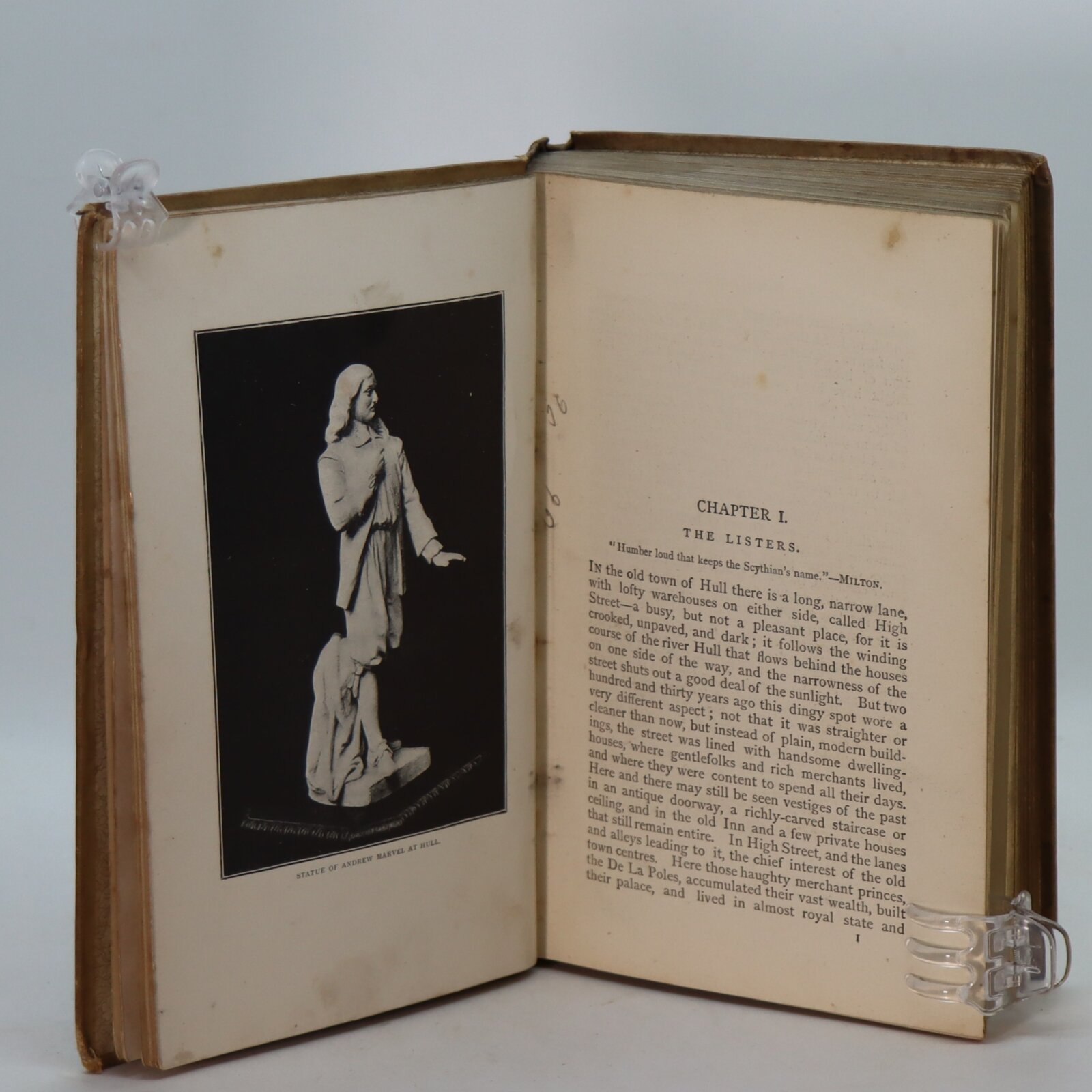

Andrew Marvell 31 March 1621 – 16 August 1678 was an English metaphysical poet, satirist and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1659 and 1678. During the Commonwealth period he was a colleague and friend of John Milton. His poems range from the love-song “To His Coy Mistress”, to evocations of an aristocratic country house and garden in “Upon Appleton House” and “The Garden”, the political address “An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland”, and the later personal and political satires “Flecknoe” and “The Character of Holland”.

After Marvell’s death a collection of his Miscellaneous Poems was issued in 1681 by Robert Boulter, one of the original publishers of Paradise Lost, who that summer was to be arrested for predicting the imminent fall of the monarchy. The prefatory note, dated 15 October 1680 and signed ‘Mary Marvell’, describes them as being ‘Printed according to the exact Copies of my late dear Husband, under his own Hand-Writing’. It served to authenticate the contents for a general readership, to whom Marvell’s poetic talents were known, if at all, from his commendatory verses to the second edition (1674) of Milton’s epic, and perhaps from some satires. The folio volume includes religio-philosophical dialogues; verses on the pleasures (both sensuous and spiritual) of the retired life in pastoral surroundings; poems that depict innocence on the verge of sexual maturity; love lyrics, from the classic persuasion of ‘To his Coy Mistress’ to the dark complaint of ‘The Unfortunate Lover’; and some Latin epigrams and epitaphs. Almost the only public response to such late-appearing metaphysical poems is Wood’s grudging statement that the volume was ‘cried up as excellent’ by those of the author’s own persuasion (Wood, Ath. Oxon., 4.232).

Failure of nerve during a temporary crisis in whig fortunes had led to excision of the three Cromwell pieces before sale from almost all known copies of the work. It is scarcely surprising therefore that the collection did not include any of the political satires that were to be claimed for Marvell in anthologies printed after the revolution of 1688, from A Collection of the Newest … Poems … Against Popery (1689) to successive editions of Poems on Affairs of State (1697–1704). Definitive authentication, hampered by lack of demonstrably authorial texts and a marked disparity in style from Marvell’s other poems, is further hindered by the tendency for a topical genre or subject to attract a number of writers. But to judge from the commonly accepted pieces, Parker’s sneering allusion to Marvell’s ‘proper trade of Lampoons and Ballads’ (Reproof, 526) was not wholly undeserved, for though they address serious issues, they do so chiefly through burlesque and ridicule. Marvell himself told Aubrey that the earl of Rochester was ‘the only man in England that had the true veine of Satyre’ (Brief Lives, 2.54, 304).

Aubrey, who knew Marvell personally in the 1670s, praised him as ‘an excellent poet in Latin or English: for Latin verses there was no man would come into competition with him’, recalling that he ‘kept bottles of wine at his lodgeings … to refresh his spirits, and exalt his Muse’. Yet he was:

in his conversation very modest and of very few words. Though he loved wine he would never drink hard in company: and was wont to say, that he would not play the good-fellow in any mans company in whose hands he would not trust his life.

In appearance he was ‘of a middling stature, pretty strong sett, roundish faced, cherry cheek’t, hazell eie, browne haire’ (Brief Lives, 2.53), a description borne out in the oil portrait, executed about 1655–60 by an unidentified artist, that was presented by Marvell’s grandnephew Robert Nettleton in 1764 to the British Museum and is now in the National Portrait Gallery. A line engraving of a related type, but with image reversed, appears as frontispiece to Miscellaneous Poems, and a smaller version was executed by John Clark for Cooke’s edition of 1726. Another oil, in Hull City Art Gallery, which belonged to Ralph Thoresby and later to Thomas Hollis, bears an inscription that gives the sitter’s age as forty-two; it was engraved by Cipriani for Hollis (1760) and by Basire for Thompson’s edition (1776). Vertue attributed to Lely a now unlocated portrait that belonged before 1726 to the Hon. Maurice Ashley, Marvell’s nephew by marriage (BL, Add. MS 23070, fol. 22v).

In September 1678 Hull voted £50 for Marvell’s funeral expenses and ‘to perpetuate his memory by a Grave-stone’ (Tupper, 373–4 n. 42), but the rector is said to have objected. Mary was buried in St Giles’s on 24 November 1687, under the surname of her first husband. In the next year Popple wrote an epitaph, of which a slightly altered version was placed on a tablet set up in the new church in 1764 by Nettleton. Verse elegies survive by John Ayloffe (Poems on Affairs of State, 1697, 160–61) and two anonymous admirers (ibid., 122–3, and Davies). Marvell’s posthumous reputation as a proto-whig defender of constitutional liberties and a ‘sincere and daring Patriot’ encouraged Thomas Cooke in 1726 to reprint the lyrics alongside the satires in a collection grandly entitled The Works of Andrew Marvell Esq. A brief biography was prefixed, and some private letters were supplied by ‘the Ladys his Nieces’ (vol. 1, p. x), daughters of William Popple. Fifty years later the same spirit led Captain Edward Thompson, a native of Hull, to publish a luxurious folio edition to which Burke and Wilkes subscribed, and Thomas Hollis and T. J. Mathias contributed material. Here the expurgated Cromwell poems were first brought to public notice.

Over the next hundred years Marvell’s poetry was increasingly praised by poets and anthologists in Britain and America, earning pride of place in Alexander Grosart’s comprehensive edition of the Complete Works in 1872. T. S. Eliot’s influential essay for the Hull tercentenary volume of 1921 pointed the way to a major critical reassessment that was facilitated by H. M. Margoliouth’s 1927 Oxford edition of the Poems and Letters and Pierre Legouis’s biographical and critical study of 1928, André Marvell. Since then the ambiguity of Marvell’s poetry and the elusiveness of his personality have helped to make him of all seventeenth-century lyrists the subject of the most extensive exegesis.

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend