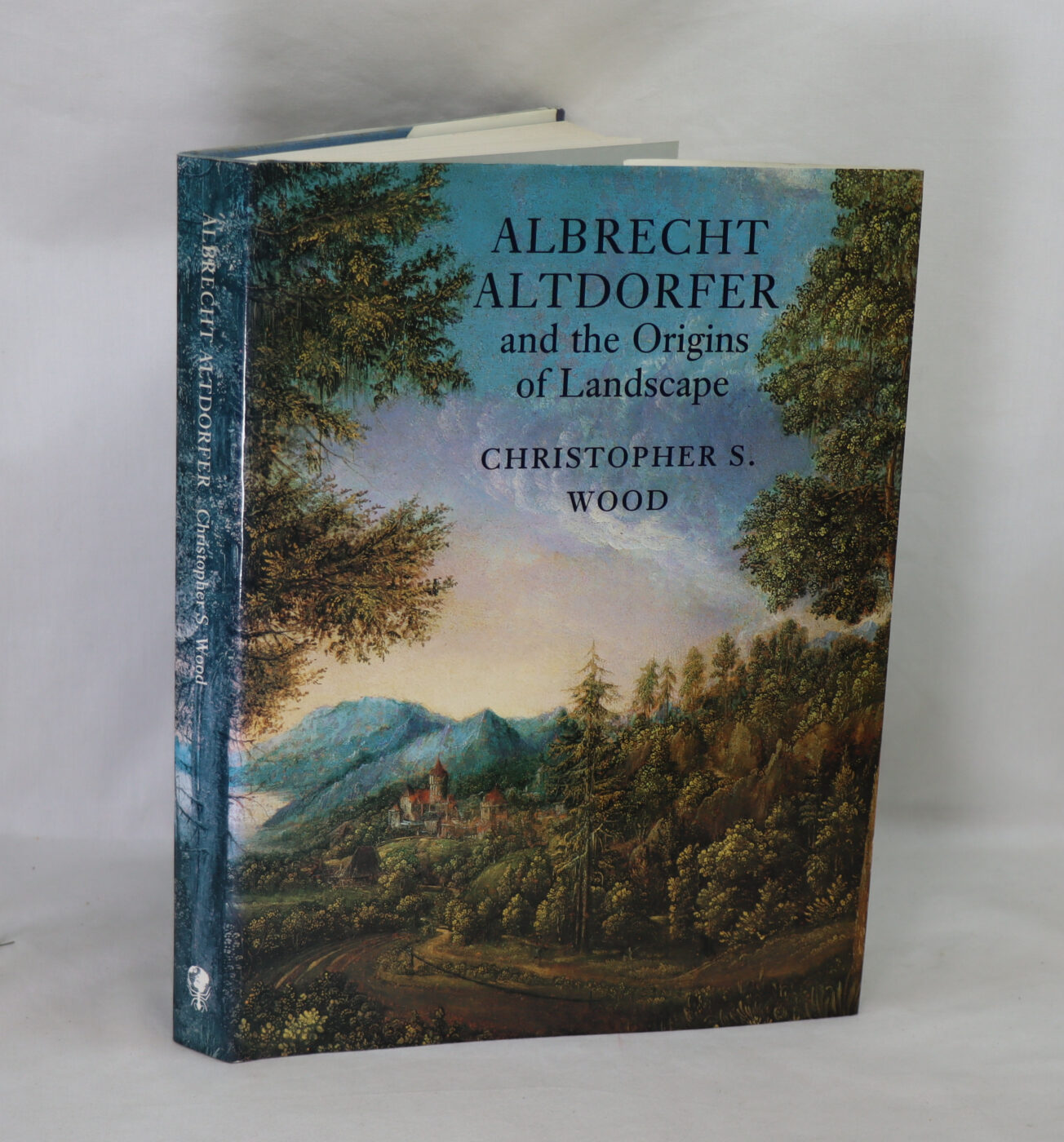

Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape.

By Christopher S Wood

ISBN: 9780226906010

Printed: 1993

Publisher: Reaktion Books. London

| Dimensions | 22 × 29 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 22 x 29 x 3

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

In the original dust jacket. Blue cloth binding with black title on the spine.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

-

Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

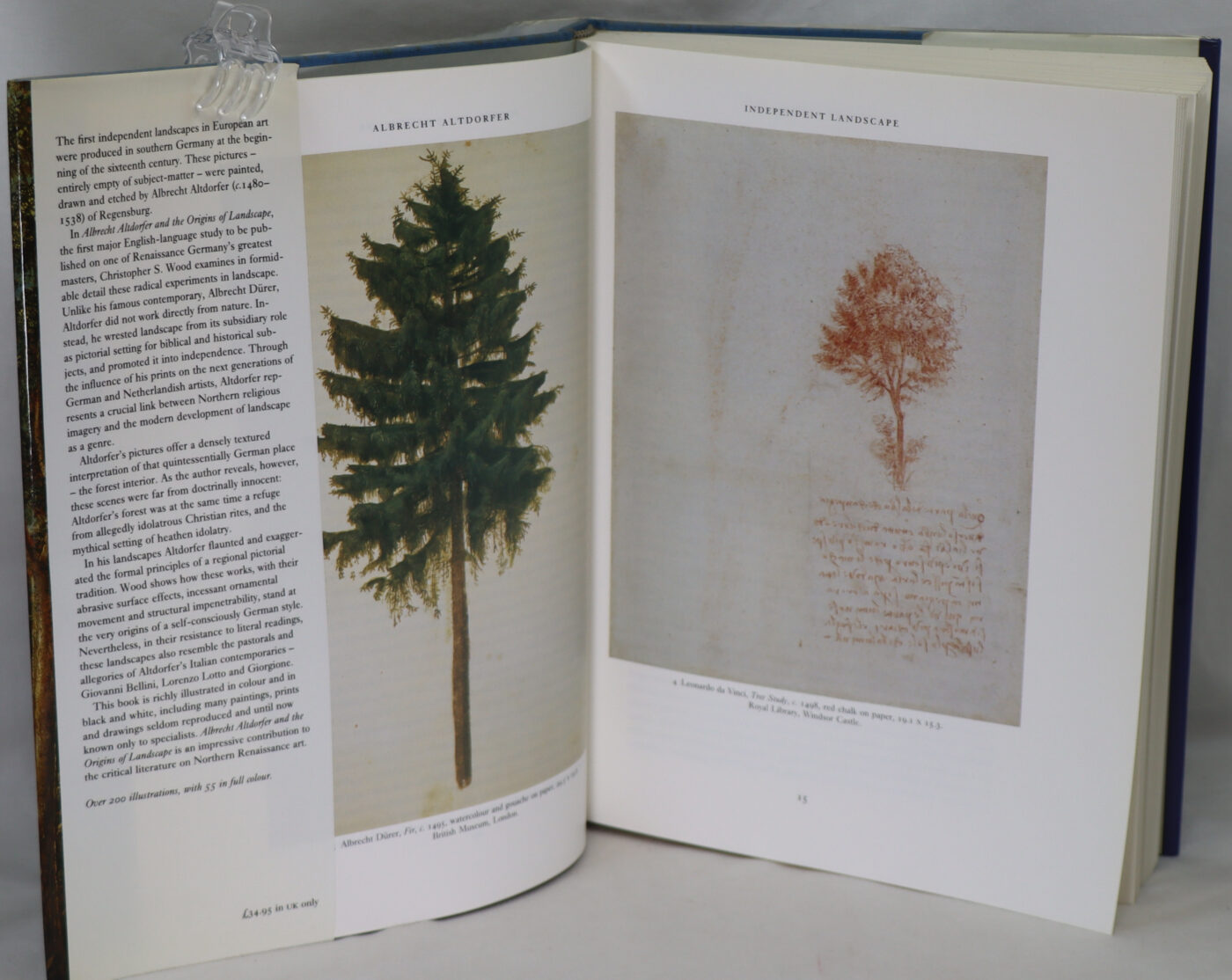

Please view the photographs for condition: in almost new condition. In the early sixteenth century, Albrecht Altdorfer promoted landscape from its traditional role as background to its new place as the focal point of a picture. His paintings, drawings, and etchings appeared almost without warning and mysteriously disappeared from view just as suddenly. In Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, Christopher S. Wood shows how Altdorfer transformed what had been the mere setting for sacred and historical figures into a principal venue for stylish draftsmanship and idiosyncratic painterly effects. At the same time, his landscapes offered a densely textured interpretation of that quintessentially German locus–the forest interior. This revised and expanded second edition contains a new introduction, revised bibliography, and fifteen additional illustrations. In this revealing study, now available in a revised and expanded new edition, Christopher Wood shows how Altdorfer prised landscape out of its subsidiary role as background for narrative history painting and devotional works to give it a new, independent life of its own. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. In the early 1500s, almost without warning, Albrecht Altdorfer promoted landscape from its traditionally supplementary role to the centre of the picture field. Christopher S. Wood shows how Altdorfer (c.1480-1538) transformed what had been the mere setting for sacred and historical figures into a principal venue for stylish draftsmanship and idiosyncratic painterly effects. In this English-language study of this artist, Wood investigates the historical conditions that supported the emergence of landscape as an independent genre in the time of Durer. He argues that Altdorfer’s work is explicable neither in terms of the “descriptive” traditions of the Low Countries nor the “discursive” mode of contemporary Italian painting; rather, it registers a third possibility of deictic, or self-referential, practice. He also reveals that Altdorfer’s forest scenes are far from doctrinally innocent: the forest that Altdorfer painted, drew, and etched is both a refuge from Christian rites and a mythical setting of idolatry. Because of Altdorfer’s influence on the next generation of German and Netherlandish artists, his work forms a crucial link between Northern religious imagery and the modern development of landscape as a genre.

Reviews:

-

When and how landscape [without a subject-matter] became for the first time to be painted as deserving its own frame? The story about Altdorfer’s extraordinary achievements told in this book is scholarly well documented (with surprises) in the context of the German culture of his time. The “how”, that is the way all that came about in terms of the painter-painting secret relationship, is brightly investigated with very personal insight: not the last word, but very stimulating. Well illustrated.

-

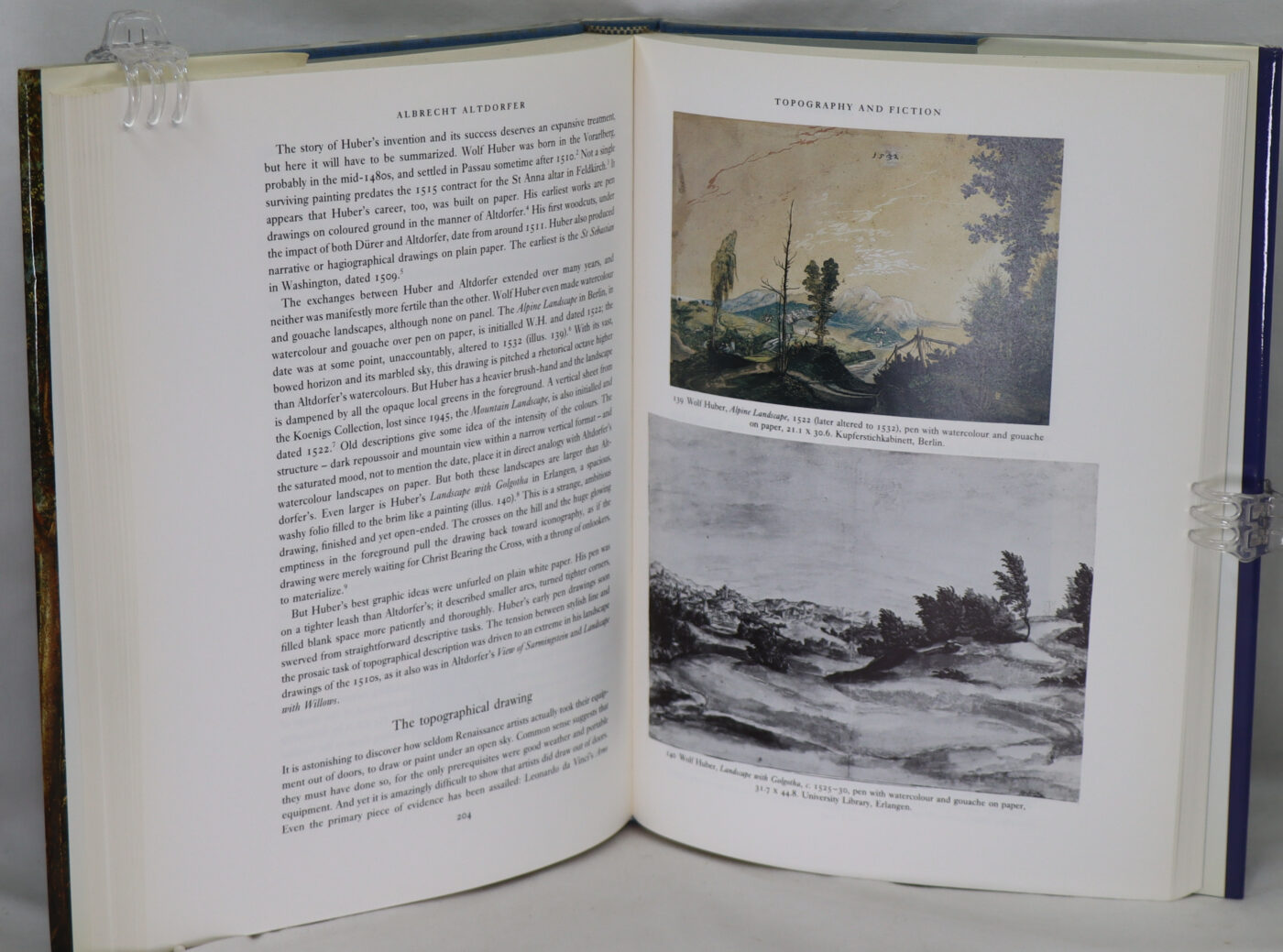

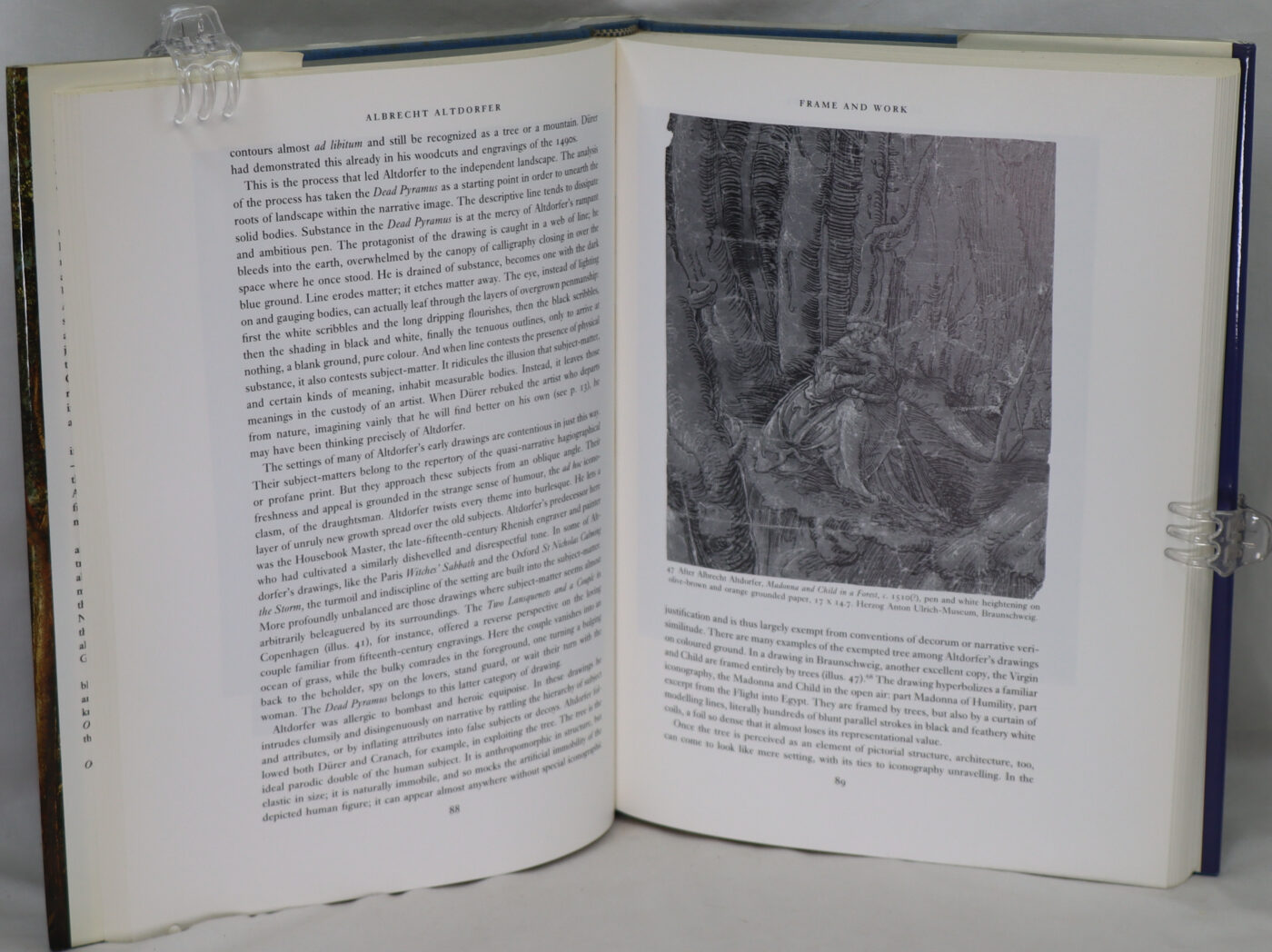

I was first introduced to this marvellous artist of the Renaissance Danube School on a visit to the monastery of St Florian, south of Linz. I blindly hoped that this book would include an analysis and appreciation of the St Florian works, but it doesn’t even feature a reproduction of any of them. Rather, this academic work is an attempt to place Altdorfer at the centre of landscape art as properly understood: indeed, Christopher Wood’s opening bold sentence is that, “The first independent landscapes in the history of European art were painted by Albrecht Altdorfer.” The book has five chapters. In the first, Wood assesses the concept of the independent landscape, pointing out that Altdorfer’s “are entirely empty of living creatures, human and animal alike. These pictures tell no stories.” He points out that the artist was very much ahead of his time, for wood panels “in southern Germany around 1500 were still largely the territory of Christian iconography. Nothing like Altdorfer’s mute landscape paintings … would be seen again until the close of the sixteenth century.” There are many art theories relating to `subject matter’ and `setting’, the `place’ of landscape in Renaissance painting, and concepts about the `frame’, Wood invoking pages and pages of thinkers from Kant to Derrida. The second chapter continues with an analysis of how Altdorfer framed his works and provides information about his life, and about those of his contemporaries in Germany and Italy: Durer and Cranach receive mention here, of course, as do Barbari, Lotto, and Giorgione, but one name missing is that of Carpaccio. We learn how in the fifteenth-century the role of the landscape was subservient to a greater purpose, “to be inserted into the backgrounds of narrative paintings.” Wood argues in the third chapter that, “The picture that actually broke with the fifteenth century” was Altdorfer’s `St George & the Dragon’ of 1510. The full page reproduction appears six pages prior to this, and one can therefore judge its special quality before the declaration is made. And indeed it does have a special quality; St George and the dragon are peripheral, superfluous, for it is the forest that is the picture. Wood calls the painting “a conversation among branches”. Earlier in this chapter Wood alludes to the special claims of the forest on the German psyche, but in `St George & the Dragon’ Altdorfer views the forest from within rather than from afar, bringing it “inside the picture frame” and making it “the structural principle of the picture”; thus, in this picture “landscape became independent.” In the following chapter, Wood even attempts to envision `plein air’ drawing on the Danube, as he posits links with Altdorfer’s contemporary Wolf Huber: “The old model-book landscapes [seen in altarpieces and illuminated manuscripts of the fifteenth century] … were all fictions. So were Huber’s and Altdorfer’s drawings. The only difference was that the new fictions referred formally and structurally to an original outdoor encounter, even if that encounter never actually happened. … These are highly packaged topographies.” The fifth and final chapter addresses Altdorfer’s nine printed etchings, “revolutionary landscapes but they ignited no revolution.” In assessing Altdorfer’s legacy as a landscape painter, Wood sees Breughel as probably the best known. He ends his work by arguing that, “Altdorfer’s landscapes initiate not the history of landscape painting but the history of a possible and for the most part unrealized landscape painting that resists history, and indeed seeks refuge from history in disorderly nature.” Altdorfer’s work in this genre, then, was a one-off, a precocious idea that got lost amongst the trees of the Danubian forests. Wood clearly knows his stuff, but the writing style is alas sometimes abstruse and arcane, addressing the cognoscenti rather than the general reader. It is often full of the art-historical aesthetic academies: try swallowing this, for example – “To dispel these various nostalgias for nature, one must preserve the critical insight that pictures themselves actually generate ideas about nature, and at the same time refrain from dismissing that `secondary’ image of nature as the phantasm of the aesthetic ideology.” Wood is no Ruskin, no Berenson, no Panofsky, or Schama. The book is reasonably well-illustrated. There are 203 illustrations, the book’s blurb says: some of these are in colour and full-page, many are neither, and some are so small (for example 6cm x 4cm) as to be useless. Wood often refers to illustrations “liberal with colour and superfluous detail”, but alas the reproductions are rarely so. Twenty-six pages of notes; a bibliography; a checklist of Altdorfer’s landscapes; a list of the book’s illustrations; and an index bring the volume to an end.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend