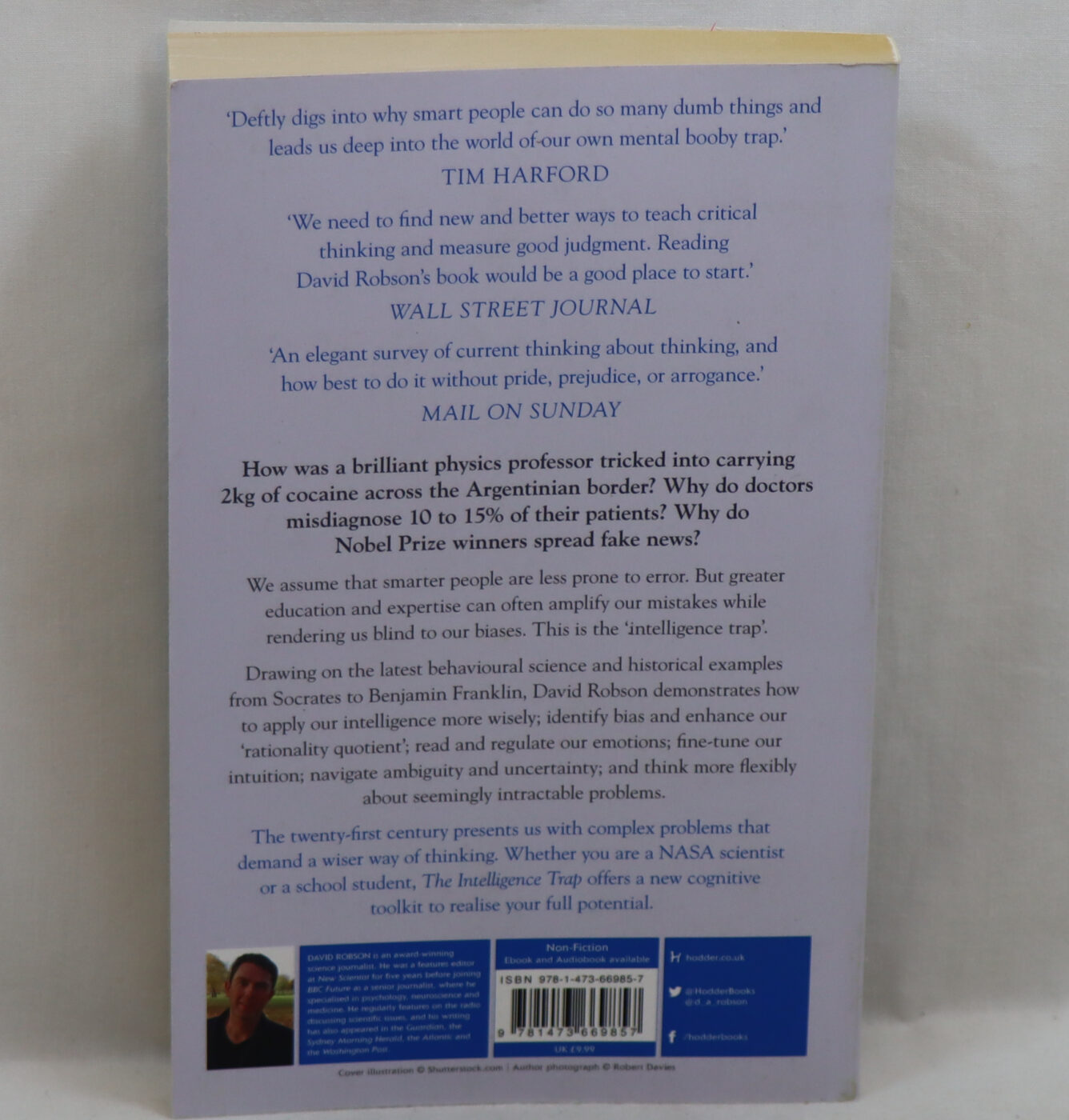

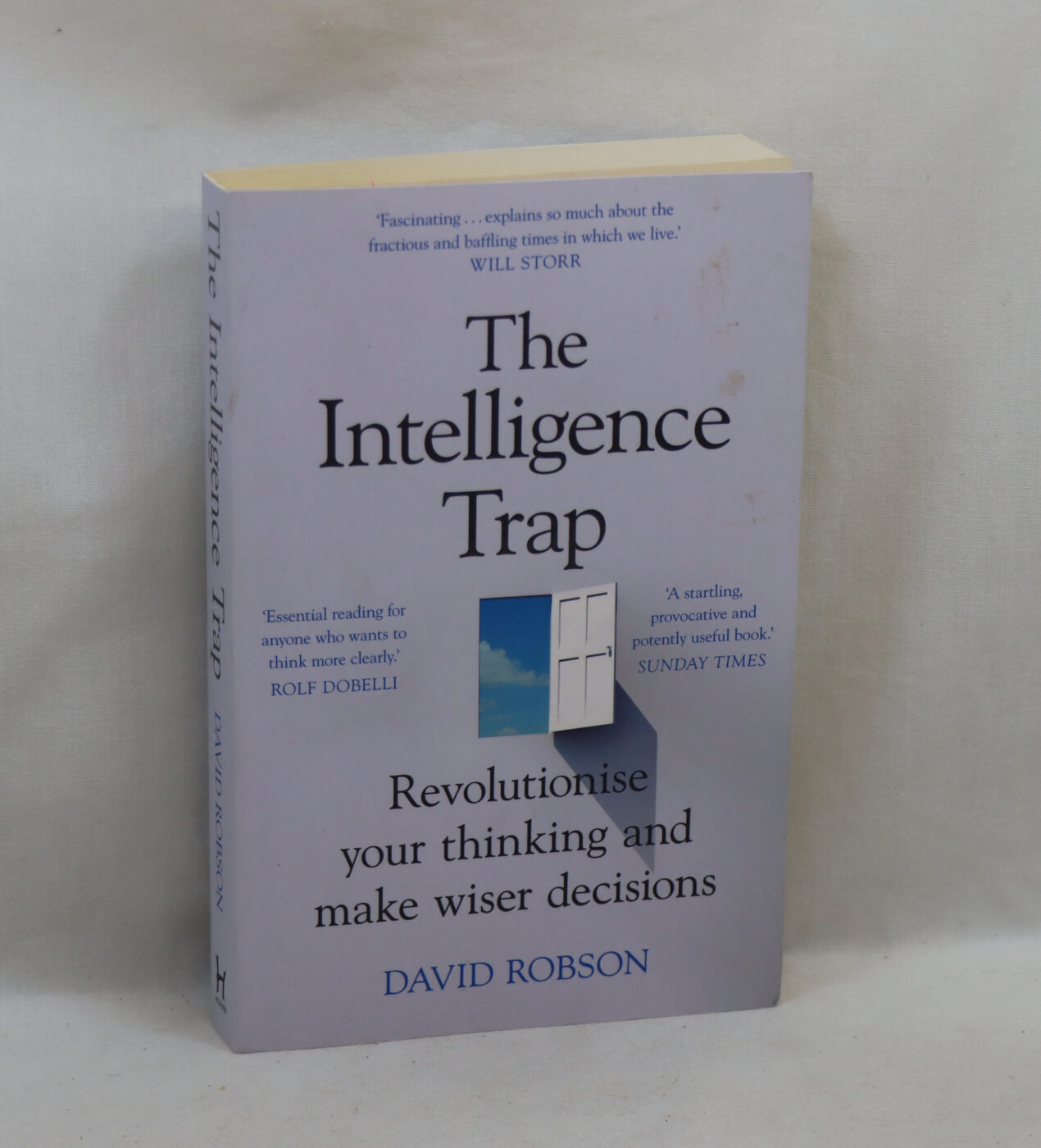

The Intelligence Trap.

By David Robson

ISBN: 9781473669857

Printed: 2020

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton. London

| Dimensions | 13 × 20 × 2 cm |

|---|

Language: Not stated

Size (cminches): 13 x 20 x 2

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Paperback. Light blue cover with black title.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

-

THIS FROST PAPERBACK is a USED book which a member of the Frost family has checked for condition, cleanliness, completeness and readability. When the buyer collects their book from Frost’s shop, the delivery charge of £3.00 is deducted.

For conditions, please view our photographs. An original book from the library gathered by the famous Cambridge Don, computer scientist, food and wine connoisseur, Jack Arnold LANG.

-

‘Essential reading for anyone who wants to think more clearly’ ROLF DOBELLI

-

‘Ceaselessly fascinating and brilliantly written’ WILL STORR

-

‘A startling, provocative and potently useful book’ SUNDAY TIMES

-

A toolkit to help smart people overcome their blind spots and maximise their potential, from the author of The Expectation Effect.

We assume that smarter people are less prone to error. But education and expertise can sometimes make our mistakes worse and our blind spots bigger. Why did genius Steve Jobs make errors of judgement? Why do doctors misdiagnose 10-15% of their patients? Why do Nobel Prize winners spread fake news? This is the intelligence trap.

Drawing on the latest behavioural science and great brains from Socrates to Benjamin Franklin, David Robson demonstrates how to apply our intelligence more wisely. He shows us how we can identify bias, read and regulate our emotions, fine-tune our intuition, navigate ambiguity and uncertainty and think more flexibly.

Whether you are a NASA scientist or a school student, The Intelligence Trap offers a new toolkit to realise your full potential.

Review: David Robson considers in a stimulating and readable way how smart people come to act stupidly. Early in the book he discusses the lasting influence of Lewis Terman, an American educational psychologist in the early 20th century. Terman believed that the results, (IQ), of an intelligence test administered on one occasion gave an all-important measure of raw brainpower and an excellent prediction of achievement throughout life. Such a viewpoint can foster feelings of worthlessness in low scorers, and arrogance with ‘earned dogmatism’ in high scorers. Earned dogmatism is when our perceptions of our own ability make us feel we have gained the right to be closed-minded and belittle other points of view. Terman’s granddaughter painted a vivid picture of family dinners in which place settings were in order of intelligence, according to a test taken years previously.

David Robson agrees that IQ tests do reflect something very important about the ability to learn and process complex information, an ability particularly useful in academia and several professions. He moves on to discuss other qualities important for success in life. Such qualities include Sternberg’s descriptions of analytical, creative and practical abilities.

In his second chapter Robson deals with a variety of biases likely to affect our thinking; he also expresses views very dismissive of the paranormal. By paranormal, I understand observations and experiences that conflict with a purely materialist world view. My Amazon review of the book Illusory Souls by G.M. Woerlee challenges this mainstream dominant viewpoint and gives insight into some of my biases.

For readers like me, who do not have ready access to specialist journals and libraries, Google Scholar allows the free download of many high-quality articles, some relating to the paranormal including An assessment of the Evidence for Psychic Functioning by Utts. This paper can be downloaded by going to Google Scholar, keying in ‘Jessica Utts’, scrolling down till the title appears, then clicking on the PDF sign to download. Similarly, key in ‘Sheldrake and Smart 2003’, then download Experimental Tests for Telephone Telepathy; then one can key in ‘Jim B Tucker 2008’ and download Ian Stevenson and cases of the Reincarnation Type.

Maybe David Robson’s dismissal of the paranormal is a rare ‘bias blind spot’*. Perhaps he would counter that my arguments are examples of ‘motivated reasoning’*, with

carefully selected evidence and rationalisation. Such is the stimulation of psychodynamic disagreement.

Robson expresses mixed feelings about intuition. On the one hand, in the appendix, he describes ‘cognitive miserliness’ as a tendency to base our decision- making on intuition rather than analysis. While on the other hand he devotes the chapter titled ‘Your Emotional Compass’ to discussing how one sort of valuable intuition can be founded on finely tuned emotional sensitivity.

Chapter 3 focuses on strengths and weaknesses of experts. An expert tends to organise great areas of information into chunks, or schemas, and is then able to come to a good decision surprisingly easily and quickly by pattern recognition. However, in times of change, old schemas may interfere with new ones, also reliance on schemas reduces ability to notice details irrelevant in the old schema but which might be highly relevant in new circumstances. Although experts may wisely reject irrelevant comments from non-experts, they need to be specially on guard against feeling expert outside their field of expertise, ‘meta-forgetfulness’, and ‘earned dogmatism’*. Being an expert gives one no immunity from some of the usual biases.

To minimise such vulnerabilities Robson devotes chapter 4 to evidence-based wisdom. This wisdom involves intellectual humility, with the ability to seek out information that runs counter to one’s original point of view, coupled with an awareness of the inherent uncertainty in our judgements. When strong emotions interfere with this approach Robson suggests various forms of self-distancing. Such wisdom may be related to health and happiness but is poorly correlated with intelligence, though it does tend to increase with age in Western cultures.

Educational systems are not dealt with until chapter 8. Robson writes approvingly of some Oriental systems that are supportive of persistence in learning even through confusing complexity. In contrast, schools in the USA and UK value quick superficial answers and avoid confusing pupils with complexity: lessons are often ‘simplified’ so that the chosen story can be digested as quickly as possible, and memorised, with alternative interpretations glossed over. Thus Western culture paves the way for the rigid thinking associated with the intelligence trap.

So far, attention has been devoted to individuals. However, man is a social animal and much that is important depends on teamwork and in the collective output of large organisations.

For teamwork, in chapter 9 Robson considers a variety of work and sport situations. He cites studies indicating that collective intelligence is only moderately related to average IQ. One of the strongest predictors of group success seems related to the social sensitivity of the team members, and the most destructive dynamic is when team members compete against each other instead of working together. In team sports there seems an optimum proportion of ‘star’ players. Graphs are shown of success in football and in basketball plotted against the percentage of top talent in the team. Robson notes, from Galansky’s analysis of over 5000 Himalayan expeditions, that teams likely to have had a hierarchical style of leadership were more likely to reach the summit but were also more likely to lose team members in the attempt. For selecting an ideal team Robson concludes that there should be less emphasis on outstanding individual abilities and more attention to interpersonal skills that enhance the team’s functioning. Although some executives feel that personal humility undermines their authority, Robson argues that employees under a humble leader are more likely to share information and work together.

In chapter 10 Robson describes a variety of disasters that have occurred with major organisations and discusses how certain corporate cultures can exacerbate individual thinking errors and inhibit wiser reasoning. An executive may come to chase short-term gains, particularly if feeling threatened by time, financial or other constraints, giving rise to ‘functional stupidity’ where any criticism is discouraged and seen as negativity: employees may then find it easier to avoid thinking, to nod along, and escape being perceived as troublemakers. (The UK has a very poor record in its treatment of ‘whistleblowers’). Many disasters are preceded by ‘near misses’ with ‘outcome bias’. In outcome bias people dismiss a near miss, without reflection, because the outcome was benign, rather than taking it as a serious warning requiring urgent attention. People are more likely to report near misses when safety is emphasised. Robson concludes that wise decision-making for large organisations is similar to that in individuals:- Both should humbly accept their limits and the possibility of failure. Both should be open to new information, including information counter to the current viewpoint, and be able to live with uncertainty and ambiguity. His appendix deftly summarises many of the concepts described in the book. The book encourages reflection and is well worth reading.

David Robson is an award-winning science writer based in London, UK, specialising in medicine, psychology and neuroscience. He has worked as a features editor at New Scientist and a senior journalist at the BBC. His writing has also appeared in the Guardian, the Times, the Observer, the Wall Street Journal, and the Atlantic. He is the author of The Intelligence Trap, The Expectation Effect, which won the British Psychological Society Book Award, and The Intelligence Trap. His latest book is The Laws of Connection.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend