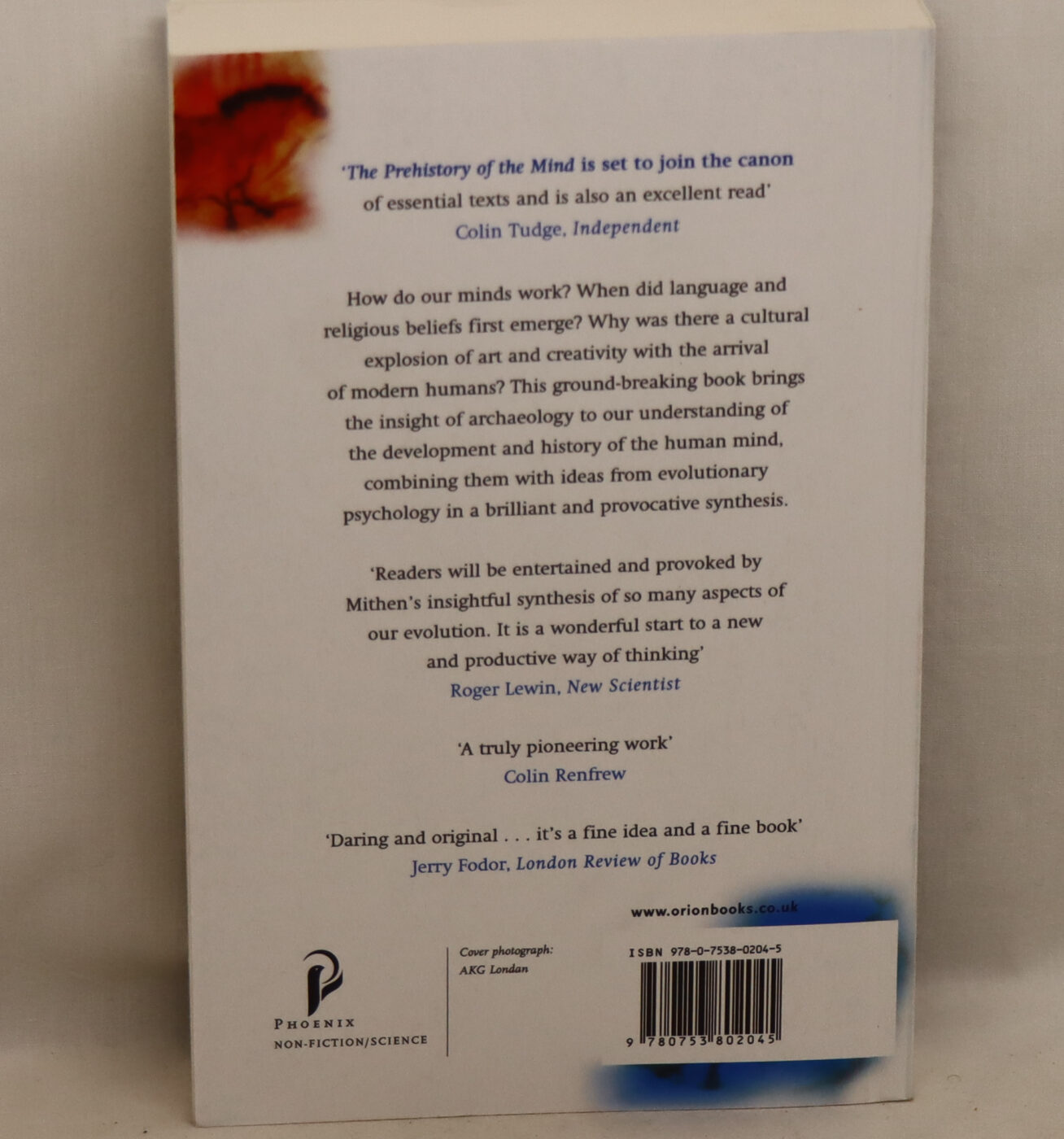

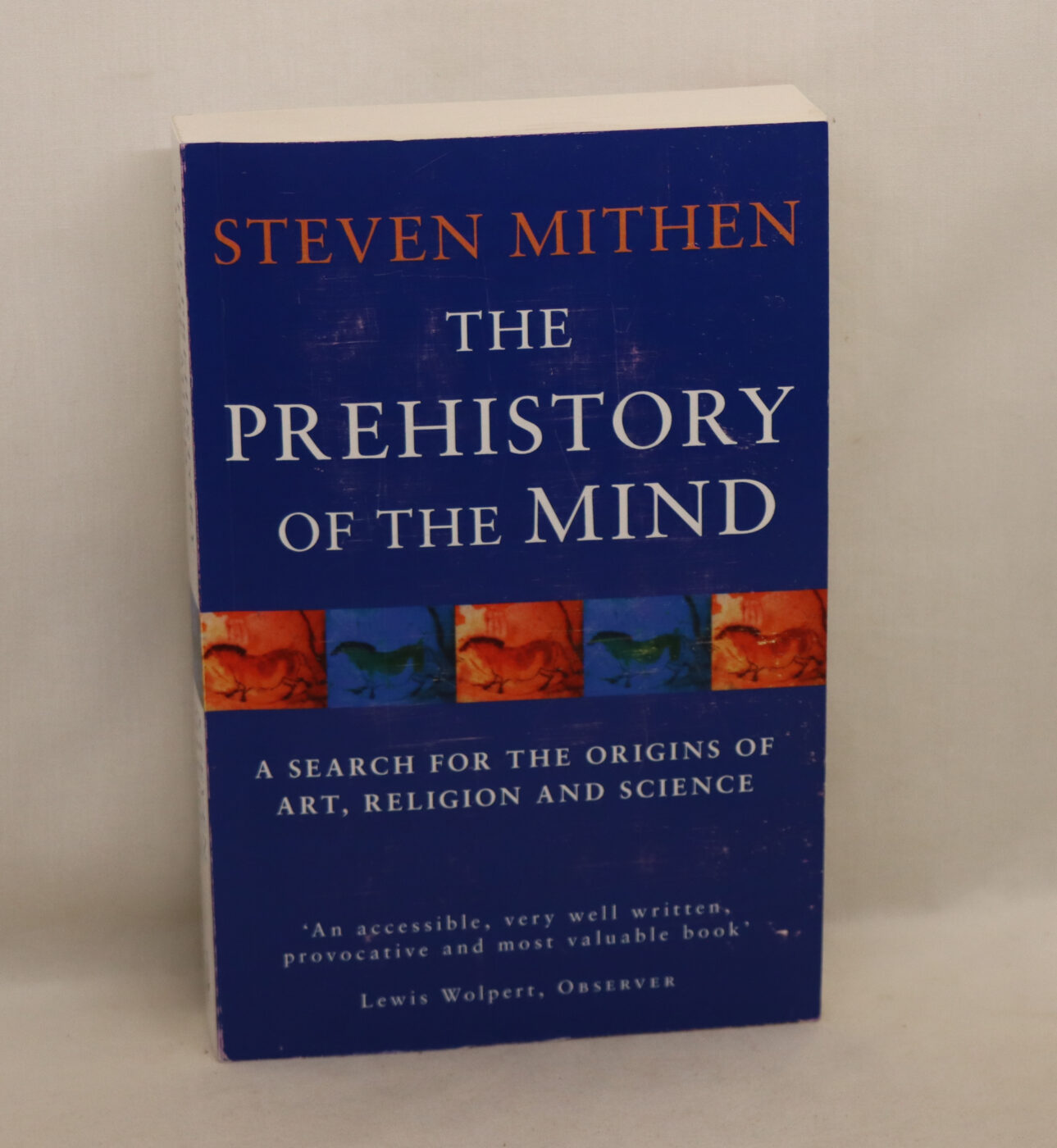

The Prehistory of the Mind.

By Steven Mithen

ISBN: 9780753802045

Printed: 1998

Publisher: Phoenix. London

| Dimensions | 13 × 20 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 13 x 20 x 3

Condition: As new (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Paperback. Orange and blue and white binding with white title.

-

THIS FROST PAPERBACK is a NEW book which a member of the Frost family has checked for condition, cleanliness, completeness and readability. When the buyer collects their book from Frost’s shop, the delivery charge of £3.00 is deducted

Award-winning science writer Steven Mithen explores how an understanding of our ancestors and their development can illuminate our brains and behaviour today. How do our minds work? When did language and religious beliefs first emerge? Why was there a cultural explosion of art and creativity with the arrival of modern humans? This ground-breaking book brings the insight of archaeology to our understanding of the development and history of the human mind, combining them with ideas from evolutionary psychology in a brilliant and provocative synthesis.

Review: Figuring out how our minds work is hard enough without also asking how they got that way. What hope is there of ever pinning down something as intangible as a million-year-old mind? And by digging up bones! What can archaeology possibly say about our almost unlimited imagination, our capacity for science, art, religion? A great deal, apparently, and the achievement of Steven Mithen in this splendid book is to make a convincing case for how stone tools, bits of bone and carved figurines can all contribute to our understanding of the modern human mind, the defining property of which he identifies as cognitive fluidity. This, put simply, is how the different parts of the mind – for example, the social, technical and natural history intelligences – are not only connected but can interact in new ways not available to an older “Swiss-army-knife mentality”.

Psychologists have used several analogies to understand the mind, which is like a sponge, “indiscriminately soaking up whatever information is around”, or like a computer running a small set of general-purpose programs (this was Piaget’s firm belief), or like a collection of specialized tools (the Swiss-army-knife or modular view). These models all have difficulty explaining the one thing the mind does that is distinctively human, its ability to create, to think of things which are not “out there”, in the world. Mithen meets this challenge with his own analogy: the mind is like a cathedral, with side chapels coming off the central nave, but with the possibility of more connections being formed between the side chapels themselves. It is this connectivity that captures the ability of one part of the mind to speak to another.

This ecclesiastical metaphor does not compromise Mithen’s scientific approach. Creationists who believe that the mind sprang suddenly into existence fully formed – “a product of divine creation” – are plain wrong. The “mind has a long evolutionary history and can be explained without recourse to supernatural powers.” When Mithen talks about cognitive architecture, the architect implied is natural selection. The time-scales are impressive: 65 million years of primate evolution, 6 million years since the common ancestor we share with our primate cousins, 4.5 million years since the oldest known human ancestor. While the evolutionary context is panoramic, Mithen’s focus is on the critical period between the appearance of stone tools 2.5 million years ago and agriculture 10,000 years ago.

Far from being a period of steady progress, however, the only major technical innovation made by Early Humans until around 250,000 years ago was the handaxe at 1.4 million years ago. The “bizarre nature of this record” – “the monotony of industrial traditions, the absence of tools made from bone and ivory, the absence of art” – “is the most compelling argument for a fundamentally different type of human mind”. It is not the case that we differ from chimpanzees or even Early Humans only in degree. Something else is needed to account for what comes next: the “two really dramatic transformations in human behaviour” associated exclusively with Modern Humans. “The first was the cultural explosion between 60,000 and 30,000 years ago, when the first art, complex technology and religion appeared. The second was the rise of farming 10,000 years ago, when people for the first time began to plant crops and domesticate animals.”

The “big bang of human culture”, Mithen claims, was made possible by the “final major re-design of the mind”, which was transformed from a set of “relatively independent cognitive domains to one in which ideas, ways of thinking and knowledge flow freely between such domains”. Anthropomorphism, for example, “is a seamless integration between social and natural history intelligence”, allowing us to attribute feelings, purposes and intentions to animals. Cat owners, as they fail once again to read the mind of their inscrutable pet, may question the benefit of such thinking, but for a hunter-gatherer better able to predict the movements of prey it could mean the difference between dinner and going hungry.

Our very capacity to invent analogies for the human mind is itself “a product of cognitive fluidity”. “Early Humans could not use metaphor because they lacked cognitive fluidity.” Our creative power has a darker side, and Mithen argues that racist attitudes are also a product of cognitive fluidity, which made possible beliefs “that other individuals or groups had different types of mind from their own” and were “less than human”, an idea which lies at the heart of racism.

Philosophers and psychologists have long considered the study of the mind as their own domain, and may bristle at the notion that the archaeological record, the empirical evidence, might be worth more than all their theorizing. The rest of us, with no such vested intellectual interests, can simply enjoy the science and marvel at the power of scientific inference to discover truths and discard untruths about the world. Mithen, like any good scientist, does not shrink from criticizing ideas he considers weak or outdated, however gilded with authority or ossified as common knowledge. For example, despite the verb “to ape” it seems that chimpanzees are not actually very good at imitating behaviour. Closer to home, while he acknowledges that “no one really understands consciousness”, he doesn’t think it beyond scientific study or so mysterious that we can say nothing about it. Following Nicholas Humphrey, he argues that “consciousness evolved as part of social intelligence” and is, at least in one important respect, a “clever trick” for reading the contents of other people’s minds.

Like all great science books, “The Prehistory of the Mind” tells us about the world and about our place in it, but Steven Mithen also tells us something about how we do the telling, and how that came about. We are creatures who can think about thinking, and who might “still be living on the savannah” were it not for two crucial behavioural developments: “bipedalism and increased meat eating”. Something to reflect upon next time you’re pacing the aisles of a supermarket, gathering food.

Award-winning science writer Steven Mithen explores how an understanding of our ancestors and their development can illuminate our brains and behaviour today. Steven Mithen is Professor of Early Prehistory and Head of the School of Human and Environmental Sciences at the University of Reading.

Want to know more about this item?

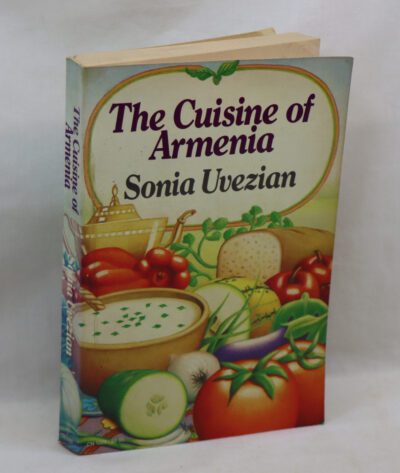

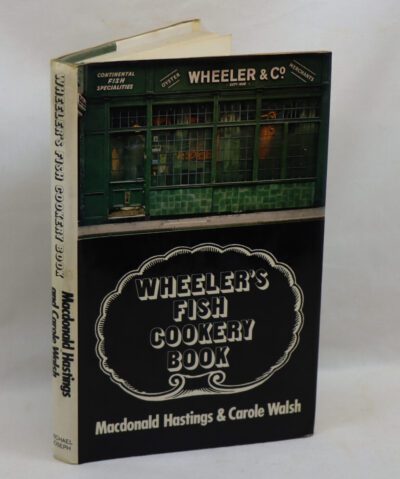

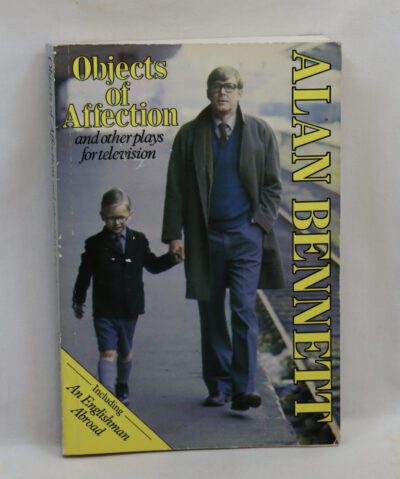

Related products

Share this Page with a friend