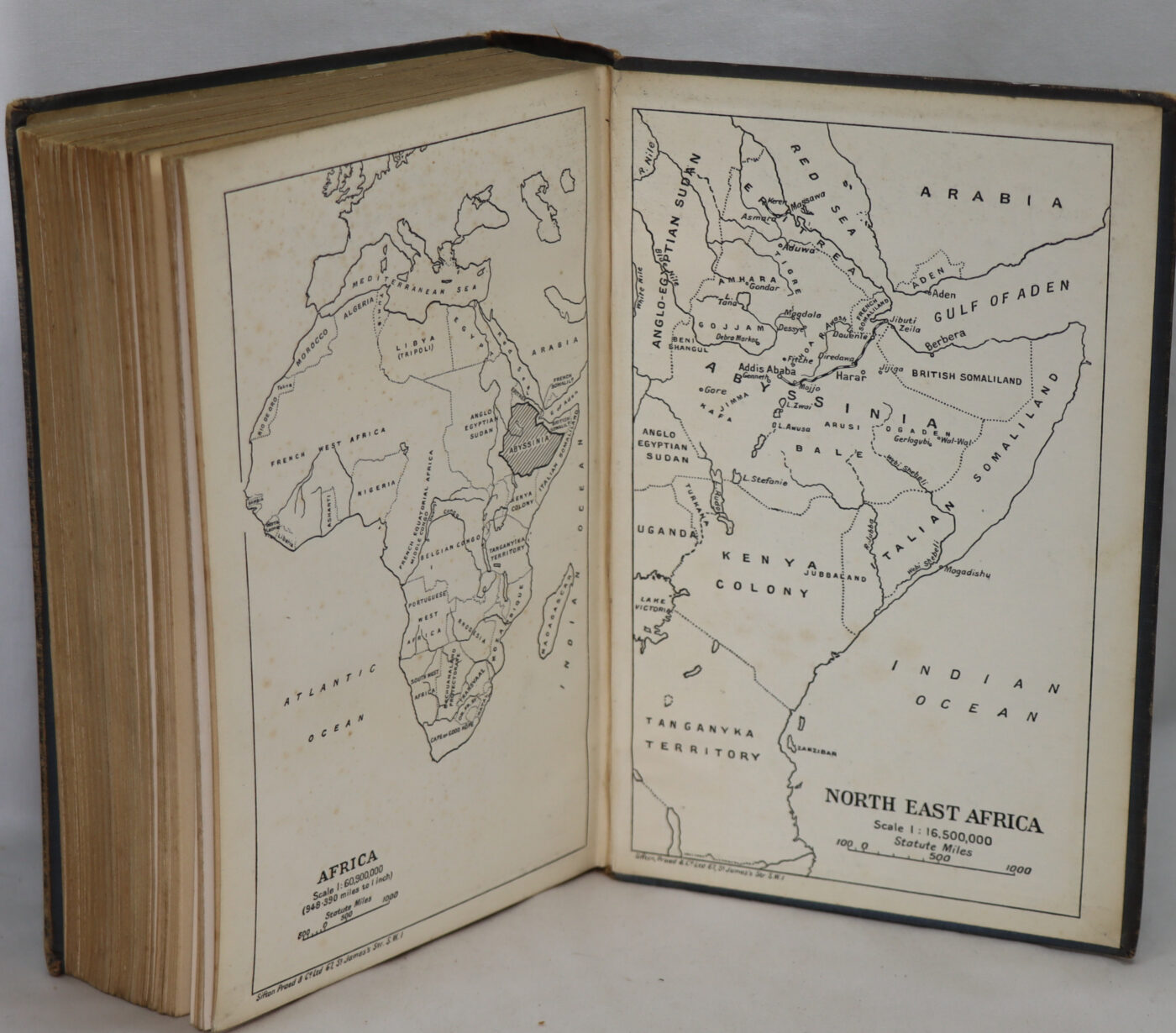

Abyssinia on the Eve.

By Ladislas Fargago

Printed: 1935

Publisher: Putnam. London

| Dimensions | 15 × 22 × 4 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 15 x 22 x 4

Condition: Fair (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Blue cloth binding with gilt title on the spine.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list

For conditions, please view our photographs. A nice clean very rare copy from the library gathered by the famous Cambridge Don, computer scientist, food and wine connoisseur, Jack Arnold LANG. This is a much underrated book written by Ladislas Faragó, a dubious CIA confidant, who misled US foreign policy for decades – and whose work still influences President Trump. An understanding of the thrust of this book will assist greatly in the comprehension of what today’s US foreign policy is.

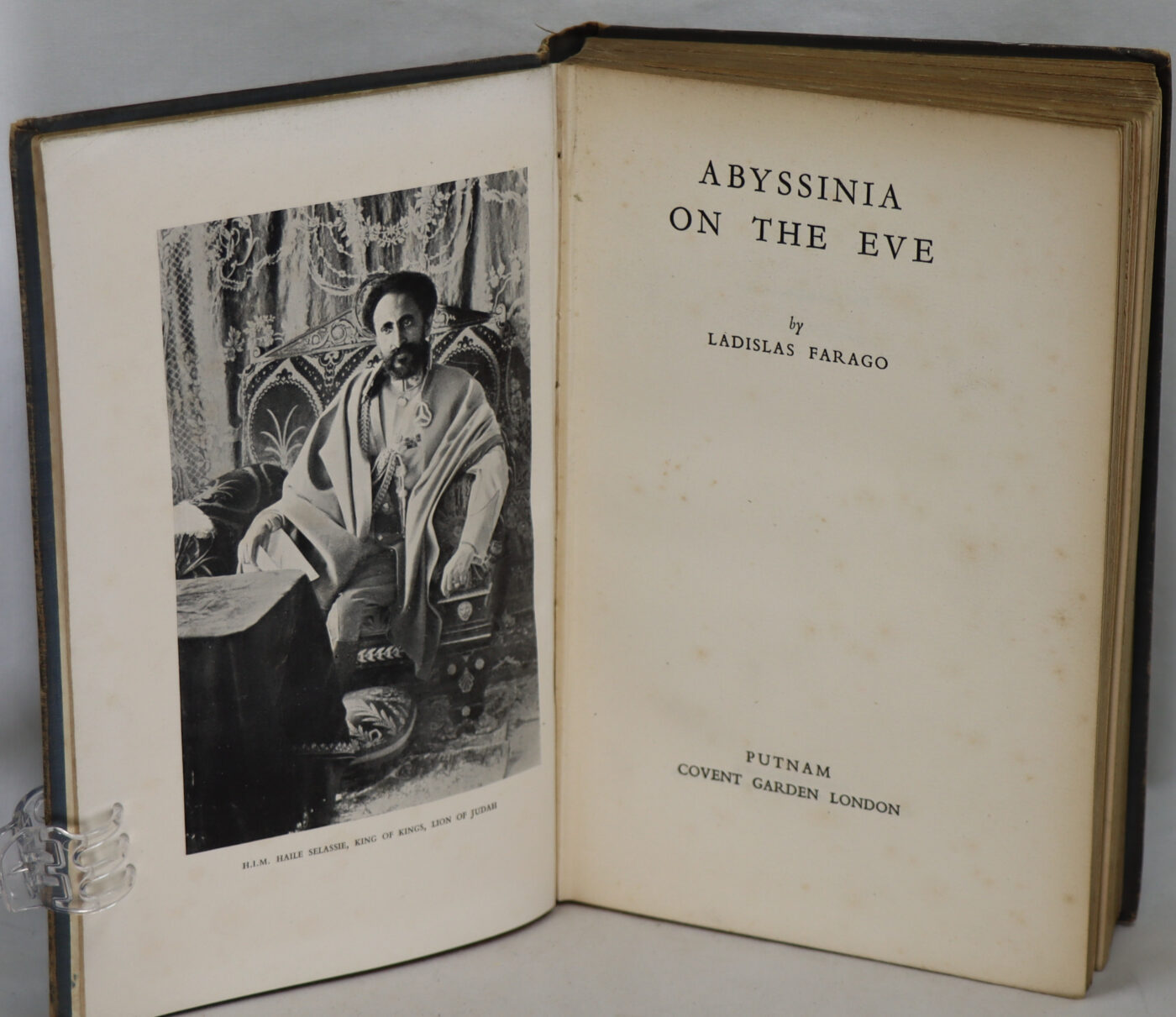

Haile Selassie I (23 July 1892 – 27 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as the Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (Enderase) under Empress Zewditu between 1916 and 1930.

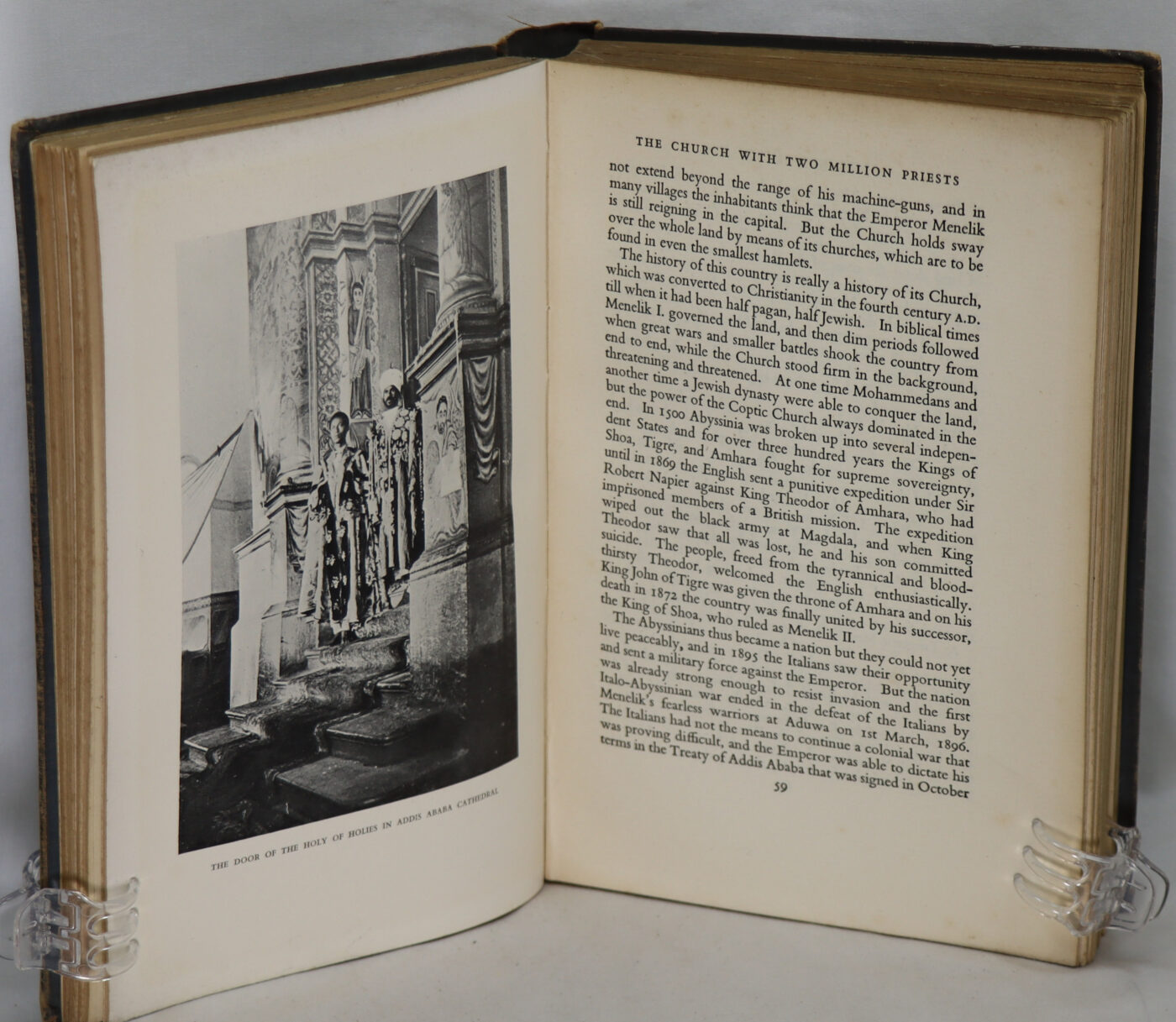

Widely considered to be a defining figure in modern Ethiopian history, he is accorded divine importance in Rastafari, an Abrahamic religion that emerged in the 1930s. A few years before he began his reign over the Ethiopian Empire, Selassie defeated Ethiopian army commander Ras Gugsa Welle Bitul, nephew of Empress Taytu Betul, at the Battle of Anchem. He belonged to the Solomonic dynasty, founded by Emperor Yekuno Amlak in 1270. Selassie, seeking to modernise Ethiopia, introduced political and social reforms including the 1931 constitution and the abolition of slavery in 1942. He led the empire during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, and after its defeat was exiled to the United Kingdom. When the Italian occupation of East Africa began, he traveled to Anglo-Egyptian Sudan to coordinate the Ethiopian struggle against Fascist Italy; he returned home after the East African campaign of World War II. He dissolved the Federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea, established by the United Nations General Assembly in 1950, and annexed Eritrea as one of Ethiopia’s provinces, while also fighting to prevent Eritrean secession. As an internationalist, Selassie led Ethiopia’s accession to the United Nations. In 1963, he presided over the formation of the Organisation of African Unity, the precursor of the African Union, and served as its first chairman. By the early 1960s, prominent African socialists such as Kwame Nkrumah envisioned the creation of a “United States of Africa”. Their rhetoric was anti-Western; Selassie saw this as a threat to his alliances. He attempted to influence a more moderate posture within the group.

Amidst popular uprisings, Selassie was overthrown by the Derg military junta in the 1974 coup d’état. With support from the Soviet Union, the Derg began governing Ethiopia as a Marxist–Leninist state. In 1994, three years after the fall of the Derg regime, it was revealed to the public that the Derg had assassinated Selassie at the Jubilee Palace in Addis Ababa on 27 August 1975. On 5 November 2000, his excavated remains were buried at the Holy Trinity Cathedral of Addis Ababa.

Among adherents of Rastafari, Selassie is called the returned Jesus, although he was an adherent of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church himself. He has been criticised for his suppression of rebellions among the landed aristocracy (Mesafint), which consistently opposed his changes. Others have criticised Ethiopia’s failure to modernise rapidly enough. During his reign, the Harari people were persecuted and many left their homes. His administration was criticised as autocratic and illiberal by groups such as Human Rights Watch. According to some sources, late into Selassie’s administration, the Oromo language was banned from education, public speaking and use in administration, though there was never a law that criminalised any language. His government relocated many Amhara people into southern Ethiopia.

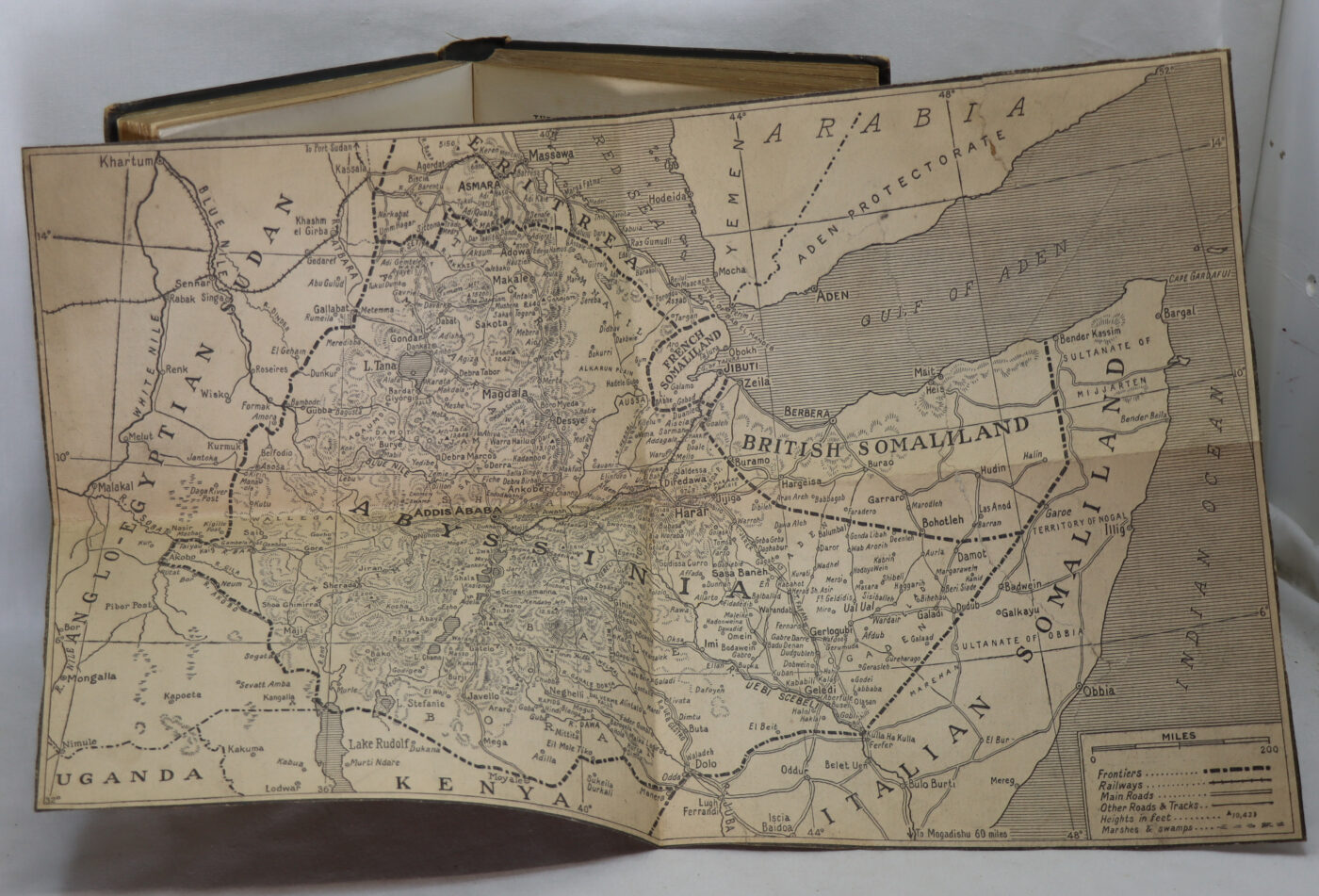

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression waged by Italy against Ethiopia, which lasted from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Italian Invasion and in Italy as the Ethiopian War. It is seen as an example of the expansionist policy that characterized the Axis powers and the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations before the outbreak of World War II. On 3 October 1935, two hundred thousand soldiers of the Italian Army commanded by Marshal Emilio De Bono attacked from Eritrea (then an Italian colonial possession) without prior declaration of war. At the same time a minor force under General Rodolfo Graziani attacked from Italian Somalia. On 6 October, Adwa was conquered, a symbolic place for the Italian army because of the defeat at the Battle of Adwa by the Ethiopian army during the First Italo-Ethiopian War. On 15 October, Italian troops seized Aksum, and an obelisk adorning the city was torn from its site and sent to Rome to be placed symbolically in front of the building of the Ministry of Colonies. Exasperated by De Bono’s slow and cautious progress, Italian prime minister Benito Mussolini replaced him with General Pietro Badoglio. Ethiopian forces attacked the newly arrived invading army and launched a counterattack in December 1935, but their poorly armed forces could not resist for long against the modern weapons of the Italians. Even the communications service of the Ethiopian forces depended on foot messengers, as they did not have radio. It was enough for the Italians to impose a narrow fence on Ethiopian detachments to leave them unaware of the movements of their own army. Nazi Germany sent arms and munitions to Ethiopia because it was frustrated over Italian objections to its attempts to integrate Austria. This prolonged the war and sapped Italian resources. It would soon lead to Italy’s greater economic dependence on Germany and less interventionist policy on Austria, clearing the path for Adolf Hitler’s Anschluss.

The Ethiopian counteroffensive managed to stop the Italian advance for a few weeks, but the superiority of the Italians’ weapons (particularly heavy artillery and airstrikes with bombs and chemical weapons) prevented the Ethiopians from taking advantage of their initial successes. The Italians resumed the offensive in late January. On 31 March 1936, the Italians won a decisive victory at the Battle of Maychew, which nullified any possible organized resistance of the Ethiopians. Emperor Haile Selassie was forced to escape into exile on 2 May, and Badoglio’s forces arrived in the capital Addis Ababa on 5 May. Italy announced the annexation of the territory of Ethiopia on 7 May and Italian King Victor Emmanuel III was proclaimed emperor on 9 May. The provinces of Eritrea, Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) were united to form the Italian province of East Africa. Fighting between Italian and Ethiopian troops persisted until 19 February 1937. On the same day, an attempted assassination of Graziani led to the reprisal Yekatit 12 massacre in Addis Ababa, in which between 1,400 and 30,000 civilians were killed. Italian forces continued to suppress rebel activity by the Arbegnoch until 1939.

Italian troops used mustard gas in aerial bombardments (in violation of the Geneva Protocol and Geneva Conventions) against combatants and civilians in an attempt to discourage the Ethiopian people from supporting the resistance. Deliberate Italian attacks against ambulances and hospitals of the Red Cross were reported. By all estimates, hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian civilians died as a result of the Italian invasion, which have been described by some historians as constituting genocide. Crimes by Ethiopian troops included the use of dumdum bullets (in violation of the Hague Conventions), the killing of civilian workmen (including during the Gondrand massacre) and the mutilation of captured Eritrean Ascari and Italians (often with castration), beginning in the first weeks of war.

Ladislas Faragó (21 September 1906 – 15 October 1980) was a military historian, journalist, and author best known for his best-selling books on history and espionage, particularly focusing on World War II. Born in Hungary, he later worked extensively in the United States, including serving as an intelligence analyst for the U.S. Navy during World War II.

The British historian Stephen Dorril, in his MI6 Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service asserts that Faragó was the ‘most successful disinformer or dupe’ concerning the presence of Nazis in South America. The original text is as follows:

Investigating ‘The Nazi Menace in Argentina’, author Ronald Newton found that the historic record had been left ‘booby-trapped with an extraordinary number of hoaxes, forgeries, unanswered propaganda ploys and assorted dirty tricks’. The most successful disinformer or dupe was the American Ladislas Faragó, ‘a somewhat Hemingway-esque figure with a strong Hungarian accent and a confidential manner’, whose ‘good connections with the CIA and secret services of several European countries enabled him to investigate and publish on a non-attributable basis’ a series of half correct tales.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend