Self and Others.

By R D Laing

ISBN: 9781134640881

Printed: 1978

Publisher: Penquin Books. London

| Dimensions | 11 × 18 × 1 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 11 x 18 x 1

Condition: Fair (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

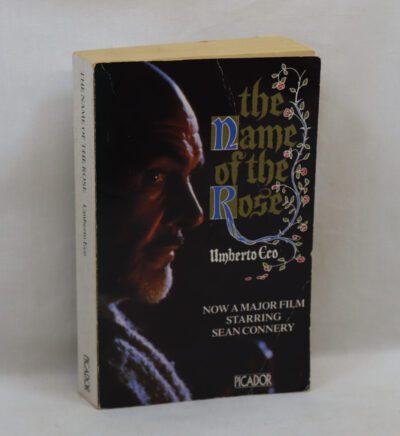

Paperback. Blue cover with black title.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

A FROST PAPERBACK is a loved book which a member of the Frost family has checked for condition, cleanliness, completeness and readability. When the buyer collects their book, the delivery charge of £3.00 is not made

A psychiatrist studies the patterns of social interaction, paying special attention to the relationship between individual experience and behavior.

Ronald David Laing (7 October 1927 – 23 August 1989), usually cited as R. D. Laing, was a Scottish psychiatrist who wrote extensively on mental illness—in particular, psychosis and schizophrenia. Laing’s views on the causes and treatment of psychopathological phenomena were influenced by his study of existential philosophy and ran counter to the chemical and electroshock methods that had become psychiatric orthodoxy. Laing took the expressed feelings of the individual patient or client as valid descriptions of personal experience rather than simply as symptoms of mental illness. Though associated in the public mind with the anti-psychiatry movement, he rejected the label. Laing regarded schizophrenia as the normal psychological adjustment to a dysfunctional social context. Politically, Laing was regarded as a thinker of the New Left. He was portrayed by David Tennant in the 2017 film Mad to Be Normal.

That Laing had read widely in humanist literature (including existential philosophy) is evident, not only in his writing, but also in his core thinking – in particular, the influence of Kierkegaard’s conception of the self is present. Laing’s central contribution is specifically that of treating patients as (albeit confused) persons in their own right – meeting them where they are, and bringing to them a firm and clear understanding of human sanity. This conception of the specifically and essentially human is therefore worth emphasising here.

The conception of the self (a person) as being the core of that what is peculiarly and preciously human, as a subject with a self-relation – relating itself to itself:

– In relating itself to itself, it relates itself to someone (or something) else, or

– In relating itself to someone (or something) else, it relates itself to itself.

Anything regarded as a subject may be conceived of relating to (eg. liking) something else. However, the specifically human is to be able to relate oneself to oneself (eg. disapproving) in relating oneself to (eg. approving of) something else.

Eg.

– I dislike myself for liking that..

– In disliking that, I find that I like myself..

Note: If one relates oneself to another as a person, one may relate oneself to the other person’s relation to oneself.

Eg. In caring how little he/she thinks of me, I find that I come to think little of myself.

Further, there is specifically the conception of the self as free (uncaused), that we (like the patient) are not simply peculiarly complicated meat, the result of various conditions and inputs. Our internal relations (decisions, attitudes, to oneself, others and things) are free (the free will). Therefore, eg. the attitude of another, however close and/or persistent, cannot be thought of as causing low self-esteem. However, it may be thought of as an opportunity/temptation for a subject to be misled (or to mislead him/herself) – a stumbling block.

The awareness of oneself as free, and the possibilities and responsibilities inherent in this, are an essential part of our (and the patient’s) internal structure – and to have this attitude (relation) to others (including patients) is an essential part of treating them as specifically human beings, rather than as eg. objects of study, problems, etc. We learn to be human primarily by being treated as human, which is to say, by being loved. A loveless relation to a patient can therefore never help them in coming to terms with the possibilities and responsibilities of being human, which is after all what they are. It is therefore also the only path which can (and must) be offered to them as a way out of any of the many confusions which may have arisen. With concrete examples, often from his own practice, Laing tries to lead the reader to this specifically human attitude in any approach to the psychiatric treatment of patients. That this attitude, and the clarity with which he portrayed it, was something new (even revelatory) to many in the psychiatric profession is by inference a judgment on how far astray, how inhuman, the practice of many professionals was at that time, and may continue to be.

Both at the time and since, many (perhaps most) of Laing’s practical expressions of this attitude have met with disapproval, and have been disregarded or even brought into disrepute. However, his specifically human conception of patients, and the consequently mandated self-regulation of professionals in their attitude toward and treatment of patients, should stand unscathed – as an outstanding contribution, not only to his particular field, but to any professional relation to persons.

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend