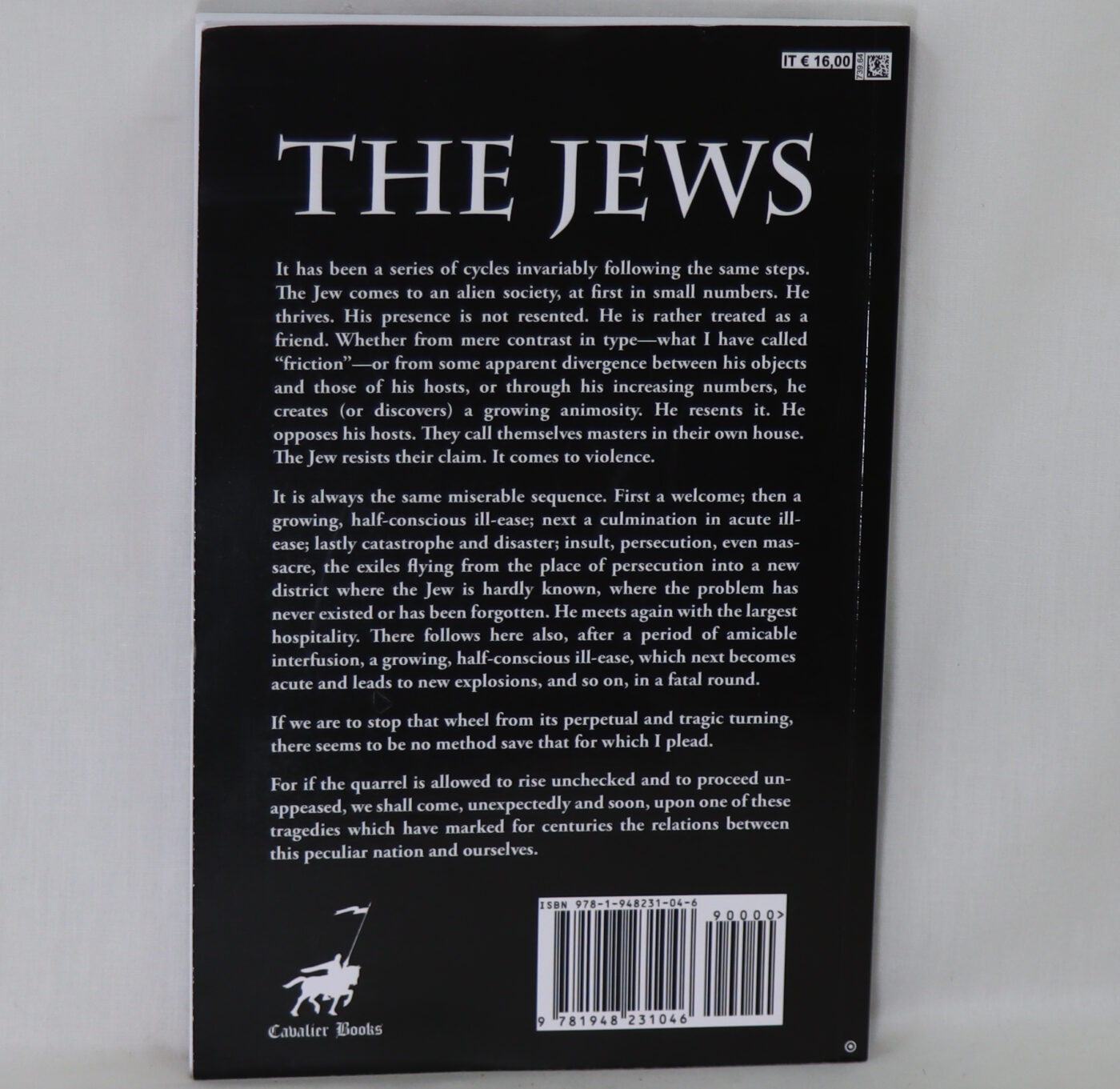

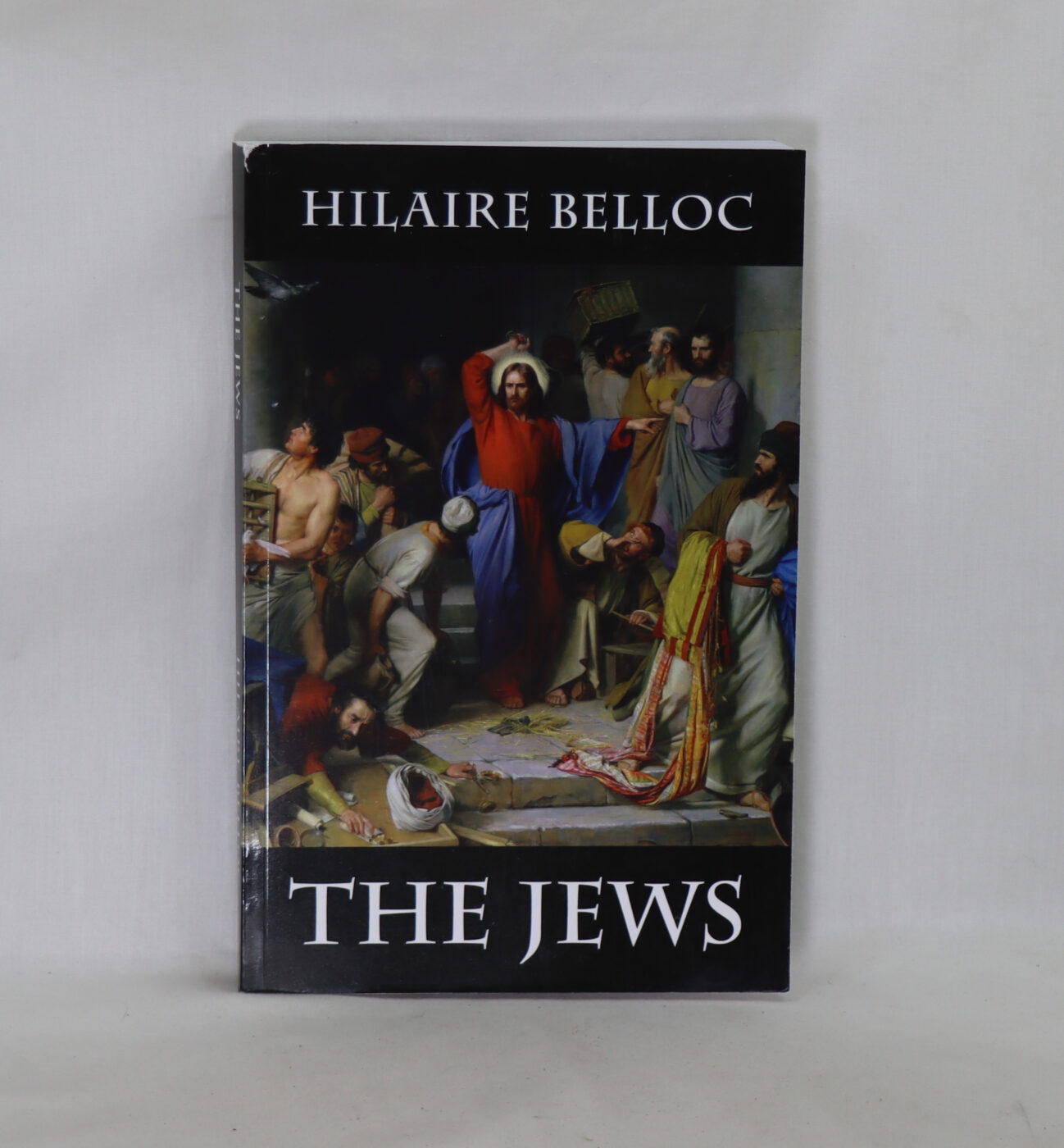

The Jews.

By Hillaire Belloc

Printed: 2018

Publisher: Cavelier Books. Milwaukee. Wisconsin

| Dimensions | 15 × 23 × 1 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 15 x 23 x 1

Condition: As new (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Paperback. Black cover with white title and biblical scene.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- This new book has a £3 discount when collected from our shop

The Jews (1922) by Hilaire Belloc, including the Introductory Chapter to the Third Edition (1937). “It has been a series of cycles invariably following the same steps. The Jew comes to an alien society, at first in small numbers. He thrives. His presence is not resented. He is rather treated as a friend. Whether from mere contrast in type—what I have called ‘friction’—or from some apparent divergence between his objects and those of his hosts, or through his increasing numbers, he creates (or discovers) a growing animosity. He resents it. He opposes his hosts. They call themselves masters in their own house. The Jew resists their claim. It comes to violence.” “It is always the same miserable sequence. First a welcome; then a growing, half-conscious ill-ease; next a culmination in acute ill-ease; lastly catastrophe and disaster; insult, persecution, even massacre, the exiles flying from the place of persecution into a new district where the Jew is hardly known, where the problem has never existed or has been forgotten. He meets again with the largest hospitality. There follows here also, after a period of amicable interfusion, a growing, half-conscious ill-ease, which next becomes acute and leads to new explosions, and so on, in a fatal round.” “If we are to stop that wheel from its perpetual and tragic turning, there seems to be no method save that for which I plead.” “For if the quarrel is allowed to rise unchecked and to proceed unappeased, we shall come, unexpectedly and soon, upon one of these tragedies which have marked for centuries the relations between this peculiar nation and ourselves.” —Hilaire Belloc, 1922.

Review: Belloc contends that in Europe and the United States, Jews and Christians are locked in a vicious circle. Jewish elites of great ability move into a particular country where they are welcomed and prosper; masses of Jews follow and friction develops; tensions rise and Jews are expelled, or undergo persecution, or worse; the guilty nation repents, Jewish elites return, and the cycle begins anew. Belloc believes the only way out of this is for both sides to admit their own weaknesses and become honest in their relationship. Belloc frankly evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of the Jews, and pulls no punches-neither does he do so when evaluating the serious flaws of the Christian host which so greatly frustrate the Jew.

Writing in 1922 (with a most interesting and ominous new preface he added in 1937), Belloc observes a contrast between the cosmopolitan Jew and his landed Christian host that was definitely more pronounced than today: in a limited sense at least, citizens of nations have become more “Jewish”, as advances in technology and transportation engender global connectivity and sympathies and fuzzier national identity. Furthermore, whereas the old idea of property used to mean primarily real estate, today it has come to include ownership of tangible and practically intangible things whose origins might be anywhere on the planet.

Regardless of such changes, there is much to be gained by reading this immensely thought-provoking book. It is quite valuable indeed for any Jewish person seeking to better understand his roots in Western culture, how Christians perceive him, and how the atrocities of the Holocaust occurred. Indeed, Belloc as much as predicted the Nazi extermination of Jews. He makes an important distinction between the anti-Semite, who seeks only to destroy the Jew, and the person who perceives a Jewish problem and seeks to address it to the advantage of all parties. Belloc in part blames the rise of anti-Semitism in the 1920’s to the Jewish tendencies to secrecy and their strategy of dismissing the anti-Semite as a stupid crank. The problem with this, Belloc contends, is that secrecy and derision undercut honest debate. As people with real grievances, or even real perceived grievances, can get no hearing, frustration builds and eventually boils over in a desire for any redress, reasonable or not: the perfect environment for the anti-Semitic fanatic. One can see this tendency in the USA today, mainly with respect to minorities other than Jews. When any criticism, valid or not, is denounced as racism or sexism or extremism, debate is stifled and people grow angry. On this point and many, many others, Belloc’s insights provide both historical instruction and suggest immediate, important application to issues that are vital today.

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (27 July 1870 – 16 July 1953) was a French-English writer, politician, and historian. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. Belloc was considered one of the most versatile authors of the 20th century. His Catholic faith had a strong effect on his works. Belloc became a naturalised British subject in 1902 while retaining his French citizenship. While attending Oxford University, he served as President of the Oxford Union. From 1906 to 1910, he served as one of the few Catholic members of the British Parliament.

Belloc was a noted disputant, with a number of long-running feuds. He was also a close friend and collaborator of G. K. Chesterton. George Bernard Shaw, a friend and frequent debate opponent of both Belloc and Chesterton, dubbed the pair the “Chesterbelloc“. Belloc’s writings encompassed religious poetry and comic verse for children. His widely sold Cautionary Tales for Children included “Jim, who ran away from his nurse, and was eaten by a lion” and “Matilda, who told lies and was burned to death”. He wrote historical biographies and numerous travel works, including The Path to Rome (1902). Belloc’s writings were at times supportive of anti-Semitism and other times condemnatory of it. Belloc took a leading role in denouncing the Marconi scandal of 1912. Belloc emphasized that key players in both the government and the Marconi corporation had been Jewish. American historian Todd Endelman identifies Catholic writers as central critics. In his opinion: ‘The most virulent attacks in the Marconi affair were launched by Hilaire Belloc and the brothers Cecil and G. K. Chesterton, whose hostility to Jews was linked to their opposition to liberalism, their backward-looking Catholicism, and the nostalgia for a medieval Catholic Europe that they imagined was ordered, harmonious, and homogeneous. The Jew baiting at the time of the Boer War and the Marconi scandal was linked to a broader protest, mounted in the main by the Radical wing of the Liberal Party, against the growing visibility of successful businessmen in national life and their challenges to what were seen as traditional English values.’ A. N. Wilson’s biography expresses the belief that Belloc tended to allude to Jews negatively in conversation, sometimes obsessively. Anthony Powell mentions in his review of that biography that in his view Belloc was thoroughly anti-Semitic, at all but a personal level. In The Cruise of the Nona, Belloc reflected equivocally on the Dreyfus Affair after thirty years. Norman Rose’s book The Cliveden Set (2000) asserts that Belloc ‘was moved by a deep vein of hysterical anti-semitism’. In his 1922 book, The Jews, Belloc argued that “the continued presence of the Jewish nation intermixed with other nations alien to it presents a permanent problem of the gravest character”, and that the “Catholic Church is the conservator of an age-long European tradition, and that tradition will never compromise with the fiction that a Jew can be other than a Jew. Wherever the Catholic Church has power, and in proportion to its power, the Jewish problem will be recognized to the full.” Robert Speaight cited a letter by Belloc in which he condemned Nesta Webster because of her accusations against “the Jews”. In February 1924, Belloc wrote to an American Jewish friend regarding an anti-Semitic book by Webster. Webster had rejected Christianity, studied Eastern religions, accepted the supposed Hindu concept of the equality of all religions and was fascinated by theories of reincarnation and ancestral memory. Speaight also points out that when faced with anti-Semitism in practice—as at elitist country clubs in the United States before World War II—he voiced his disapproval. Belloc also condemned Nazi anti-Semitism in The Catholic and the War (1940).

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend