The search for your perfect item starts here ...

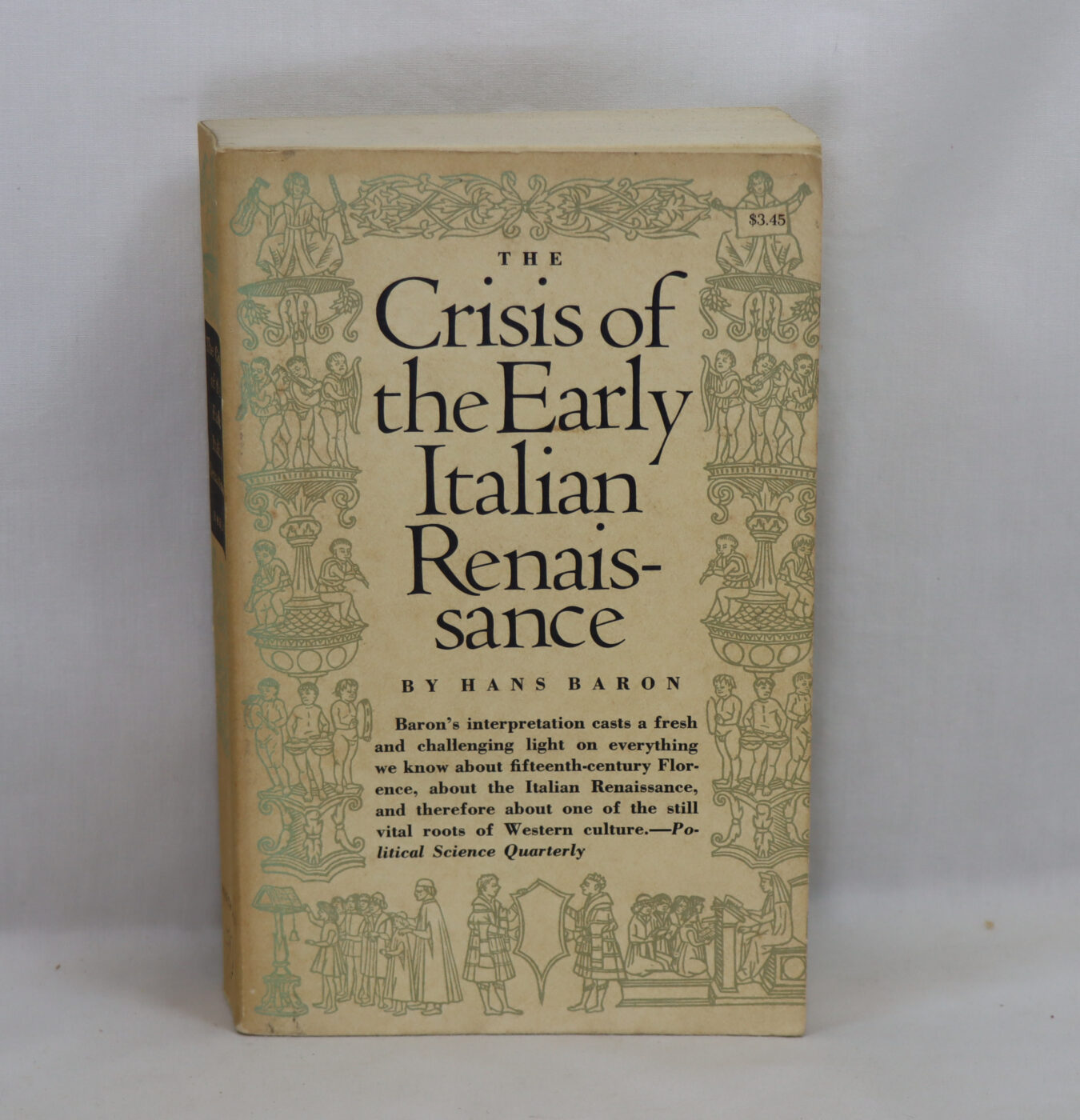

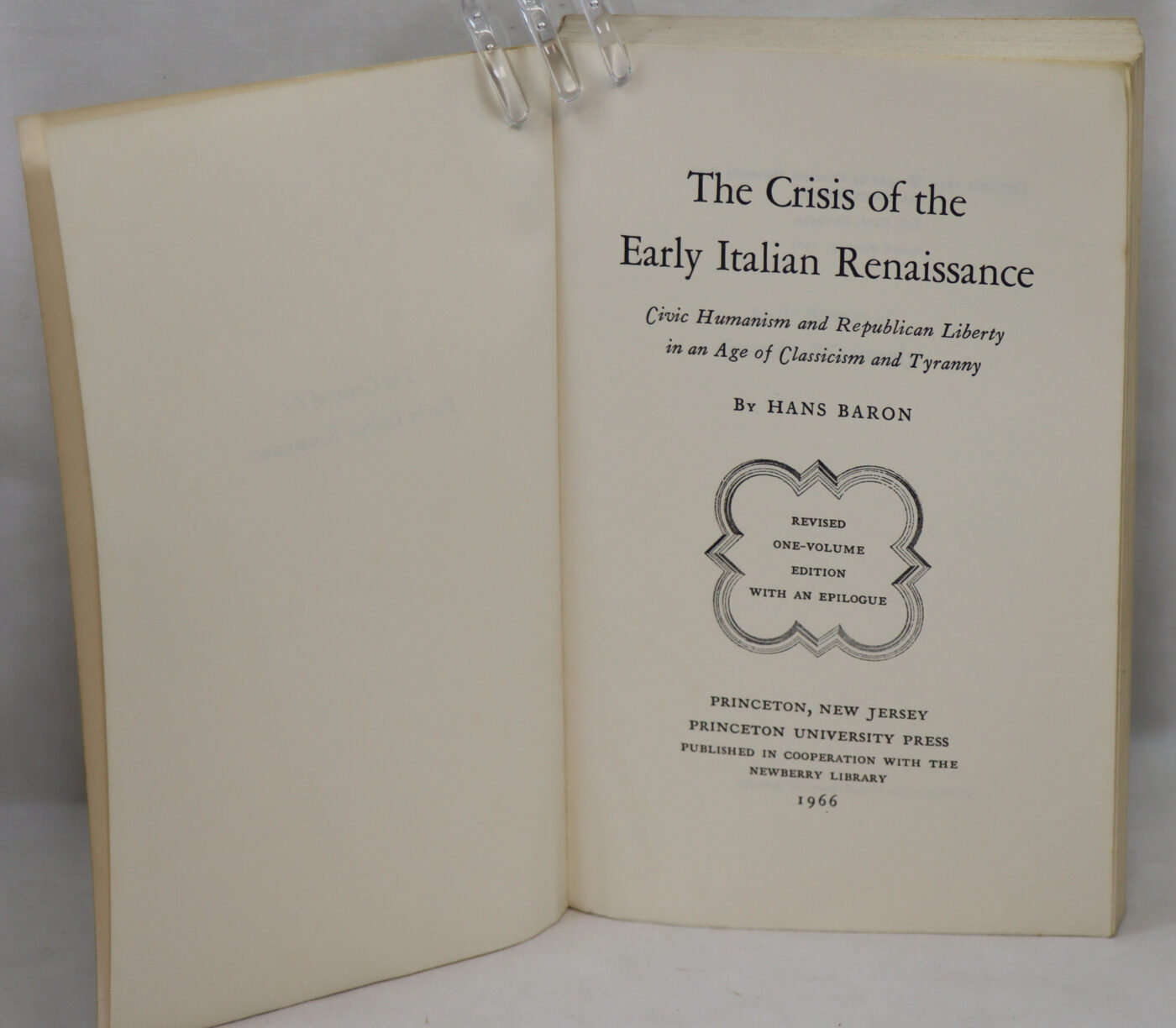

The Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance.

By Hans Baron

Printed: 1966

Publisher: Princeton University Press.

| Dimensions | 13 × 20 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 13 x 20 x 3

Condition: Good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Paperback. Cream cover with black title on the spine and on the front board.

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available

- This used book has a £3 discount when collected from our shop

For the conditions of this used book, please view our photographs.

Hans Baron was one of the many great German émigré scholars whose work Princeton brought into the Anglo-American world. His Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance has provoked more discussion and inspired more research than any other twentieth-century study of the Italian Renaissance. Baron’s book was the first historical synthesis of politics and humanism at that momentous critical juncture when Italy passed from medievalism to the thought of the Renaissance. Baron, unlike his peers, married culture and politics; he contended that to truly understand the Renaissance one must understand the rise of humanism within the political context of the day. This marked a significant departure for the field and one that changed the direction of Renaissance studies. Moreover, Baron’s book was one of the first major attempts of any sort to ground intellectual history in a fully realized historical context and thus stands at the very origins of the interdisciplinary approach that is now the core of Renaissance studies. Baron’s analysis of the forces that changed life and thought in fifteenth-century Italy was widely reviewed domestically and internationally, and scholars quickly noted that the book “will henceforth be the starting point for any general discussion of the early Renaissance” The Times Literary Supplement called it “a model of the kind of intensive study on which all understanding of cultural process must rest” First published in 1955 in two volumes, the work was reissued in a one-volume Princeton edition in 1966.

Review: Baron’s Crisis was an influential text in its day. It’s easy to understand why. The author’s impressive erudition and command of Florentine Renaissance texts of the humanists and their debates remain worthy of respect to this day. His methodology has drawn many disciples who garnered even more academic laurels than did their master. Skinner, Pocock, and even Wood owe much to Baron, I think. Baron describes the concrete “crisis” of Florence at the turn into the fifteenth century. Giangaleazzo of Milan is poised to conquer the world; or, well, most of Italy anyway. Cajoling, duplicity, threatening, and eventually military invasion have generally served his goal well, except as to Florence. She alone would stand against the all-encompassing tyranny of “Universal Monarchy”. The odds were against her. Logistics were against her. Her friends were secretly against her. And Fortune in battle sadly seemed against her. However, Giangaleazzo suddenly dies. Florence and its learned class are elated, to say the least. The eventual change of humanist political philosophy from one side of this historical event to the other constitutes the contents of this book. Baron traces the changes undergone in humanist philosophy from one deeply colored by a medieval attachment to political quietism, monarchy, and a studious withdrawal from worldly things over to an invigorated humanism steeped in the virtues of local political engagement, civic liberty, and the citizen militia. Ideas have consequences, it seems, but Baron appears to insist that we need the great man(or men) of history to illustrate this. Leonardo Bruni and Caluccio Salutati step onstage for this specific purpose. Much of this work concerns itself with close readings of their numerous texts. Baron digs deep. The details examined aren’t insignificant, but could put off the casual reader If you aren’t particularly interested whether Bruni wrote the second half of his Dialogues in 1402 but rather 1405 you may feel a drag affect. Other lesser humanists are trotted out, usually as foils to the above two. This is an interesting history of urbane gentlemen dealing with an age of political tumult and their intellectual turn toward an understanding of the importance of civic liberty. Their journey of debate rewards careful scrutiny, as Baron shows. Freedom of participation as well as the ability to serve in public office found roots in Florence in the fifteenth century for the first time according to Baron. Though concrete events may have pushed these political changes upon the republic, the Florentine humanists sold them to a much wider European public, who would in turn consume them and begin the process of making these core principles locally their own.

Hans Baron (June 22, 1900 – November 26, 1988) was a German-American historian of political thought and literature. His main contribution to the historiography of the period was to introduce in 1928 the term civic humanism (denoting most if not all of the content of classical republicanism). Born in Berlin to a Jewish family, Baron was a student of the liberal Protestant theologian Ernst Troeltsch. After Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, he left Germany, first for Italy and England, then in 1938 for the United States. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1945. He was employed as a librarian and served as Research Fellow and Bibliographer at the Newberry Library from 1949 to 1965 and was a Distinguished Research Fellow at Newberry until 1970, when he retired. He also held a teaching appointment at the University of Chicago for many years. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1964.

His most important work, The Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance (1955), theorized that a threatened invasion of the Florentine city-state by Giangaleazzo Visconti of Milan had a dramatic effect on their conception of the directionality of history. Previously believing that good necessarily prevailed, upon considering the thought-to-be impending doom of the Florentine republic at the hands of Milan, some Florentine thinkers began to think otherwise. Baron theorized that it was this shift in understanding that allowed later thinkers like Niccolò Machiavelli to construct his view that free states required a politically realistic outlook in order to survive.

Want to know more about this item?