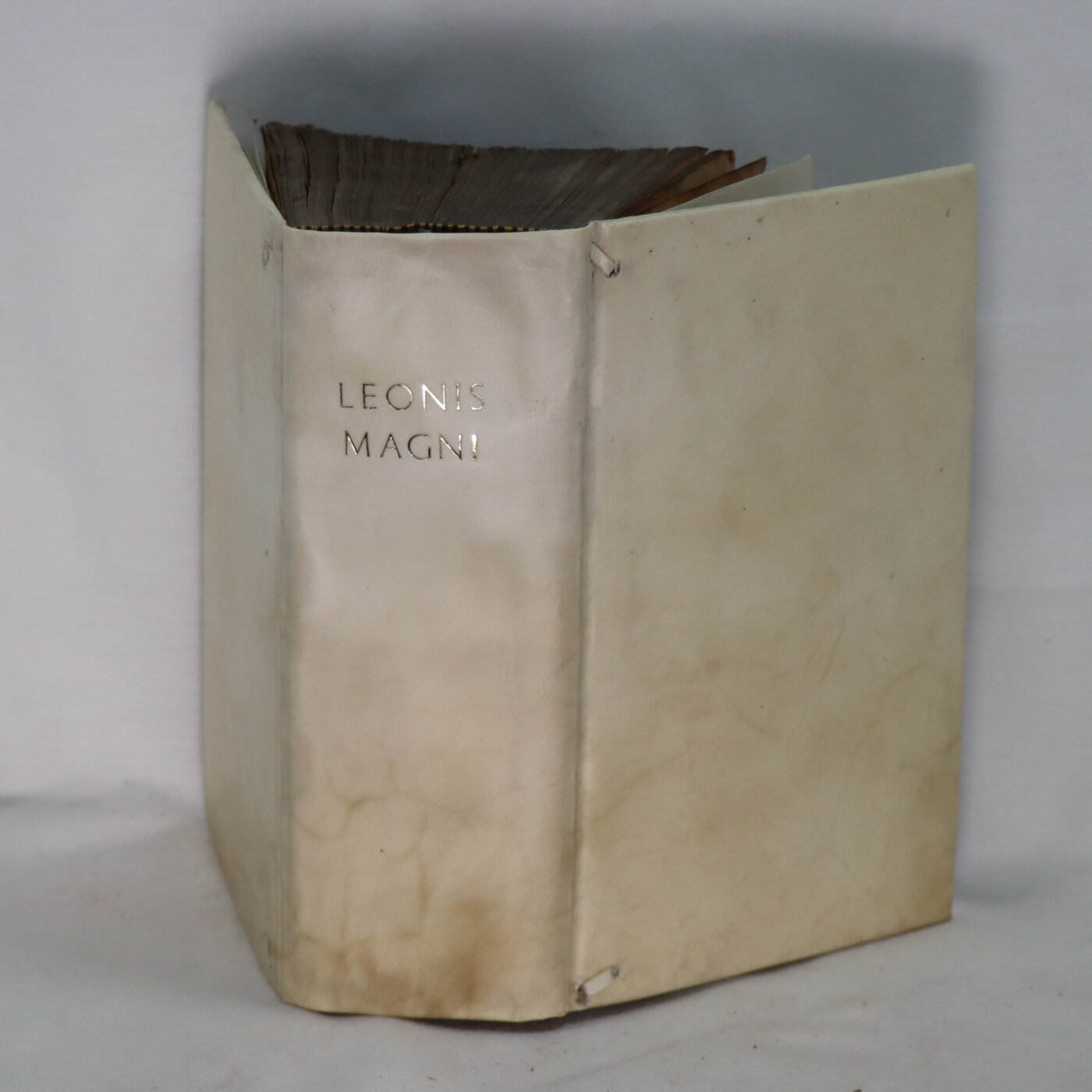

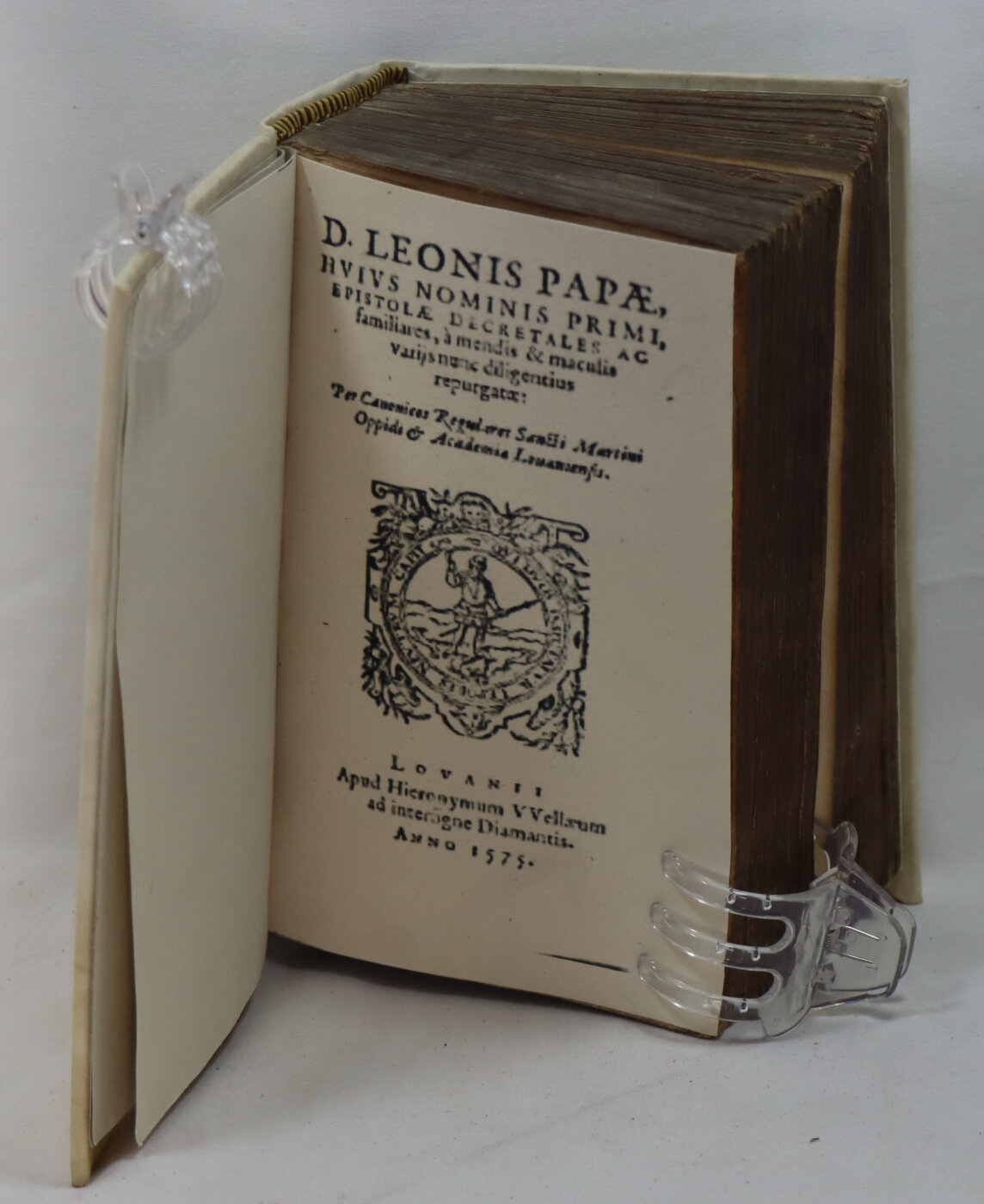

Leonis Magni.

By Leonis.

Printed: 1575

Publisher: V Vellxum. Lovanii

| Dimensions | 13 × 18 × 7 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: Latin

Size (cminches): 13 x 18 x 7

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

FREE shipping

Item information

Description

Newly rebound and restored in cream vellum binding with gilt title on the spine.

- We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.Note:

- These books carry the £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list.

This is an exceptional book printed in 1575 and published in vellum. F.B.A. has some concern about its very, early provenance in that the French appear to have once stolen this book. Hence, the massive price reduction. That said, in a historic perspective when holding this book you really do feel that you are touching history.

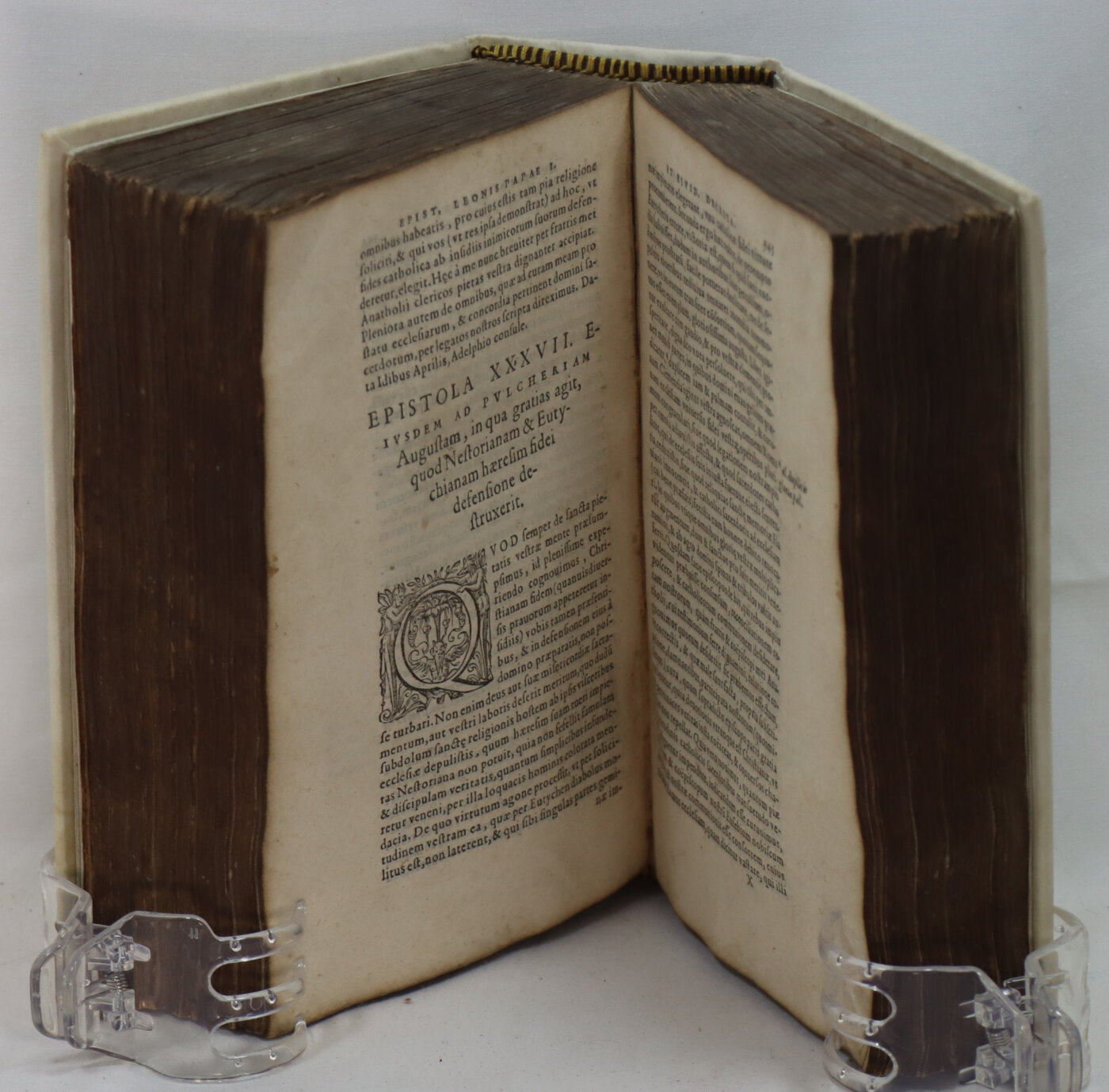

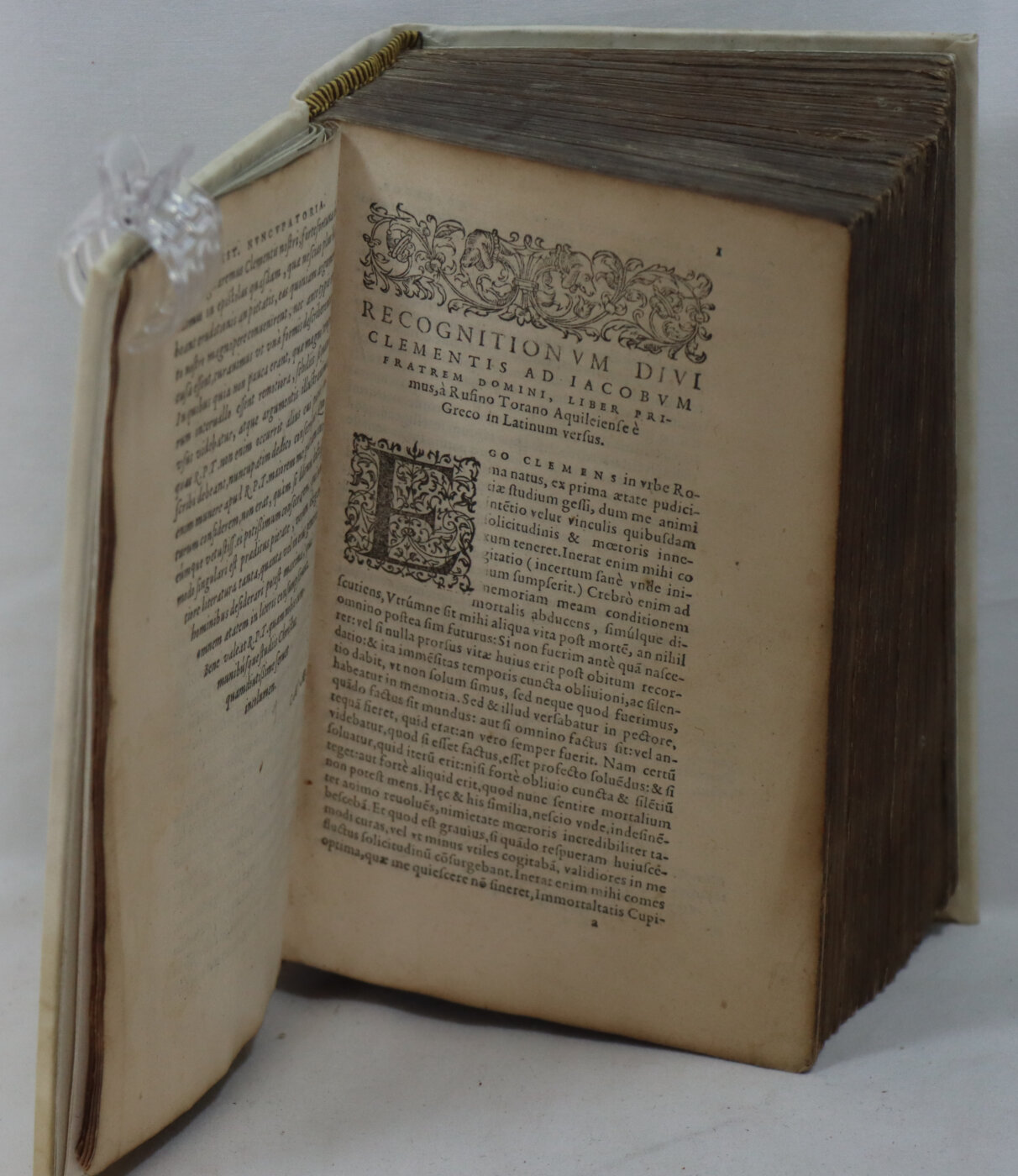

First Edition rebound in Vellum. Condition: Good. A scarce collection of sixteenth century religious texts Leonis Magnis Romani Pontificis Eius Nominis Primi, Maximi Tavrinensis Episcopi, Petri Chrysologi Ravennatis Episcopi, Fulgentii Episcopi Ruspensis & Valeriani Epsicopi Cemeliensis, Opera Omnia Qu In Latin. Three volumes bound in one. This volume is 99+% original with less than 1% being the insertion of facsimile pages to give 100% representation of the original print.

An edition, with authoritative additions of further observation and enlightenment on topics of scripture. With a scriptural index to front and further index to rear. Rebound in full vellum. Externally sound. Bright and generally clean. A Good book of the collected works of Sancti Leonis Magni (Saint Leo the Great or Saint Leo Magnus). Pope Leo I (ca. 400-461) was pope from September 29, 440 to his death in 461. He was an Italian aristocrat, and is the first pope of the Catholic Church to have been called “the Great”. He is perhaps best known for having met Attila the Hun in 452, persuading him to turn back from his invasion of Italy. The significance of Leo’s pontificate lies in his assertion of the universal jurisdiction of the Roman bishop, as expressed in his letters, and still more in his ninety-six extant orations. This assertion is commonly referred to as the doctrine of Petrine supremacy.

Pope Leo I (c. 400 – 10 November 461), also known as Leo the Great, was Bishop of Rome from 29 September 440 until his death. Leo was a Roman aristocrat, and was the first pope to have been called “the Great”. He is perhaps best known for having met Attila the Hun in 452 and persuading him to turn back from his invasion of Italy. He is also a Doctor of the Church, most remembered theologically for issuing the Tome of Leo, a document which was a major foundation to the debates of the Council of Chalcedon, the fourth ecumenical council. That meeting dealt primarily with Christology and elucidated the orthodox definition of Christ’s being as the hypostatic union of two natures, divine and human, united in one person, “with neither confusion nor division”. It was followed by a major schism associated with Monophysitism, Miaphysitism and Dyophysitism. He also contributed significantly to developing ideas of papal authority.

Early life Pope Leo I (c. 400 – 10 November 461), also known as Leo the Great,[1] was Bishop of Rome[2] from 29 September 440 until his death.

Leo was a Roman aristocrat, and was the first pope to have been called “the Great”. He is perhaps best known for having met Attila the Hun in 452 and persuading him to turn back from his invasion of Italy. He is also a Doctor of the Church, most remembered theologically for issuing the Tome of Leo, a document which was a major foundation to the debates of the Council of Chalcedon, the fourth ecumenical council. That meeting dealt primarily with Christology and elucidated the orthodox definition of Christ’s being as the hypostatic union of two natures, divine and human, united in one person, “with neither confusion nor division”. It was followed by a major schism associated with Monophysitism, Miaphysitism and Dyophysitism.He also contributed significantly to developing ideas of papal authority. According to the Liber Pontificalis, he was a native of Tuscany. By 431, as a deacon, he was sufficiently well known outside of Rome that John Cassian dedicated to him the treatise against Nestorius written at Leo’s suggestion. About this time Cyril of Alexandria appealed to Rome regarding a jurisdictional dispute with the Juvenal of Jerusalem, but it is not entirely clear whether the letter was intended for Leo in his capacity as archdeacon, or for Pope Celestine I directly. Near the end of the reign of Pope Sixtus III, Leo was dispatched at the request of Emperor Valentinian III to settle a dispute between Aëtius, one of Gaul’s chief military commanders, and the chief magistrate Albinus. Johann Peter Kirsch sees this commission as a proof of the confidence placed in the able deacon by the Imperial Court. During Leo’s absence in Gaul, Pope Sixtus III died on 11 August 440, and on 29 September Leo was unanimously elected by the people to succeed him. Soon after assuming the papal throne, Leo learned that in Aquileia, Pelagians were received into church communion without formal repudiation of their heresy; he censured this practice and directed that a provincial synod be held where such former Pelagians be required to make an unequivocal abjuration. Leo claimed that Manichaeans, possibly fleeing Vandal Africa, had come to Rome and secretly organized there. In late 443, Leo preached a series of sermons condemning the Manichaeans and calling for Romans to denounce suspected heretics to their priests. Eventually, suspected heretics were brought to court, and likely under torture, they confessed to various crimes. By early 444, Leo announced to the bishops of Italy that the Manichaeans had been eradicated from Rome. According to his contemporary Prosper of Aquitaine, Leo exposed the Manichaeans and burned their books. He was equally firm against the Priscillianist sect. Bishop Turibius of Astorga, astonished at the spread of the sect in Spain, had addressed the other Spanish bishops on the subject, sending a copy of his letter to Leo, who took the opportunity to write an extended treatise (21 July 447) against the sect, examining its false teaching in detail and calling for a Spanish general council to investigate whether it had any adherents in the episcopate. From a pastoral perspective, he energized charitable works in a Rome beset by famines, an influx of refugees, and poverty. He further associated the practice of fasting with charity and almsgiving, particularly on the occasion of the Quattro tempora, (the quarterly Ember days).It was during Leo’s papacy that the term “Pope”, which previously meant any bishop, came to exclusively mean the Bishop of Rome.

Papal authority: Leo drew many learned men about him and chose Prosper of Aquitaine to act in some secretarial or notarial capacity. Leo was a significant contributor to the centralisation of spiritual authority within the Church and in reaffirming papal authority. In 450, the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II, in a letter to Pope Leo I, was the first to call the Bishop of Rome the Patriarch of the West, a title that would continue to be used by the popes until the present days (only interrupted by a brief period between 2006 and 2024). By 447, he declared that heretics deserved the most severe punishments. The Pope justified the death penalty declaring that if the followers of a heresy were allowed to live, that would be the end of human and Divine law. According to the Liber Pontificalis, he was a native of Tuscany. By 431, as a deacon, he was sufficiently well known outside of Rome that John Cassian dedicated to him the treatise against Nestorius written at Leo’s suggestion. About this time Cyril of Alexandria appealed to Rome regarding a jurisdictional dispute with Juvenal of Jerusalem, but it is not entirely clear whether the letter was intended for Leo in his capacity as archdeacon, or for Pope Celestine I directly. Near the end of the reign of Pope Sixtus III, Leo was dispatched at the request of Emperor Valentinian III to settle a dispute between Aëtius, one of Gaul’s chief military commanders, and the chief magistrate Albinus. Johann Peter Kirsch sees this commission as a proof of the confidence placed in the able deacon by the Imperial Court.

Papacy: During Leo’s absence in Gaul, Pope Sixtus III died on 11 August 440, and on 29 September Leo was unanimously elected by the people to succeed him. Soon after assuming the papal throne, Leo learned that in Aquileia, Pelagians were received into church communion without formal repudiation of their heresy; he censured this practice and directed that a provincial synod be held where such former Pelagians be required to make an unequivocal abjuration.

Leo claimed that Manichaeans, possibly fleeing Vandal Africa, had come to Rome and secretly organized there. In late 443, Leo preached a series of sermons condemning the Manichaeans and calling for Romans to denounce suspected heretics to their priests. Eventually, suspected heretics were brought to court, and likely under torture, they confessed to various crimes. By early 444, Leo announced to the bishops of Italy that the Manichaeans had been eradicated from Rome. According to his contemporary Prosper of Aquitaine, Leo exposed the Manichaeans and burned their books. He was equally firm against the Priscillianist sect. Bishop Turibius of Astorga, astonished at the spread of the sect in Spain, had addressed the other Spanish bishops on the subject, sending a copy of his letter to Leo, who took the opportunity to write an extended treatise (21 July 447) against the sect, examining its false teaching in detail and calling for a Spanish general council to investigate whether it had any adherents in the episcopate.

From a pastoral perspective, he energized charitable works in a Rome beset by famines, an influx of refugees, and poverty. He further associated the practice of fasting with charity and almsgiving, particularly on the occasion of the Quattro tempora, (the quarterly Ember days).It was during Leo’s papacy that the term “Pope”, which previously meant any bishop, came to exclusively mean the Bishop of Rome.

Papal authority: Leo drew many learned men about him and chose Prosper of Aquitaine to act in some secretarial or notarial capacity. Leo was a significant contributor to the centralisation of spiritual authority within the Church and in reaffirming papal authority. In 450, the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II, in a letter to Pope Leo I, was the first to call the Bishop of Rome the Patriarch of the West, a title that would continue to be used by the popes until the present days (only interrupted by a brief period between 2006 and 2024).

By 447, he declared that heretics deserved the most severe punishments. The Pope justified the death penalty declaring that if the followers of a heresy were allowed to live, that would be the end of human and Divine law.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend