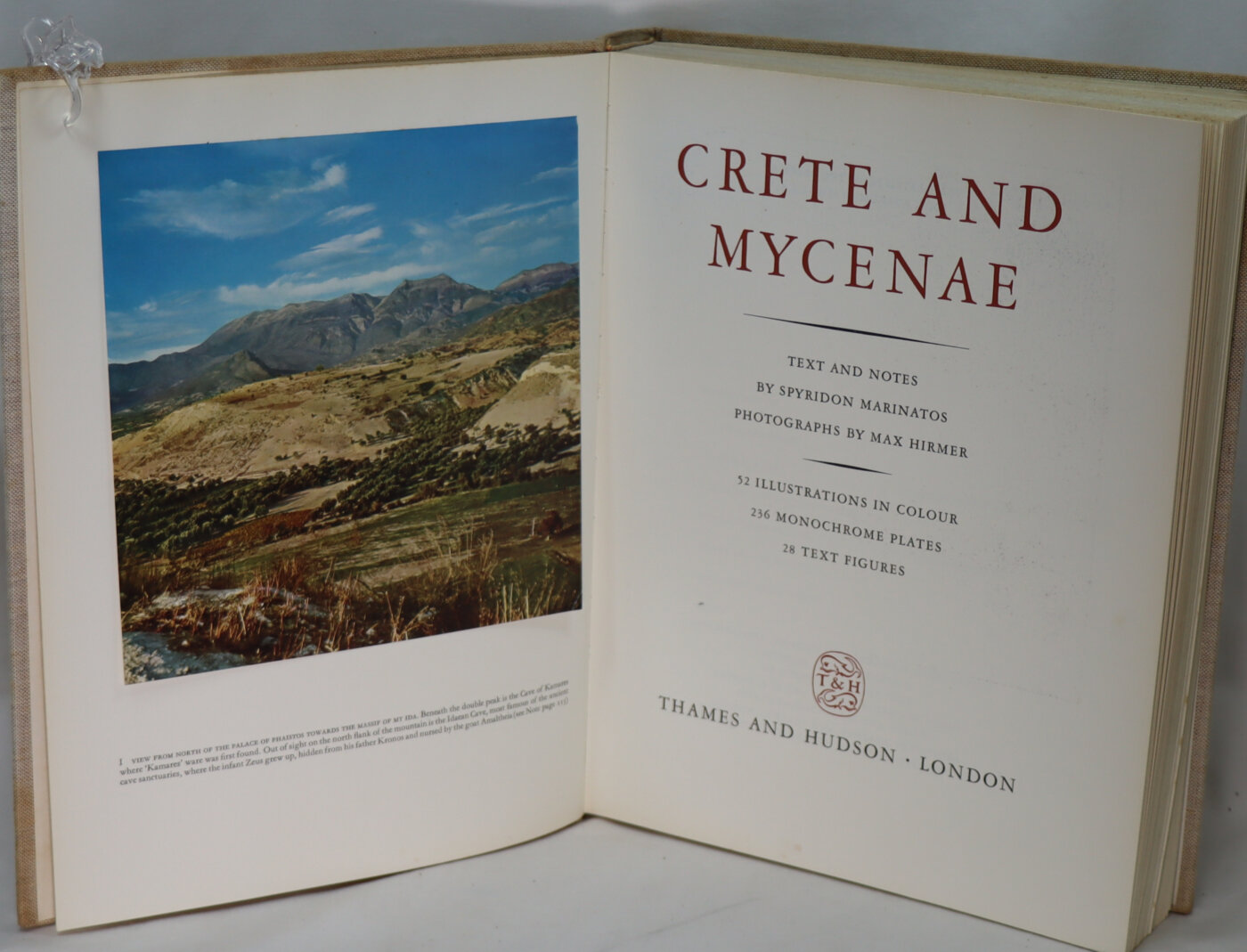

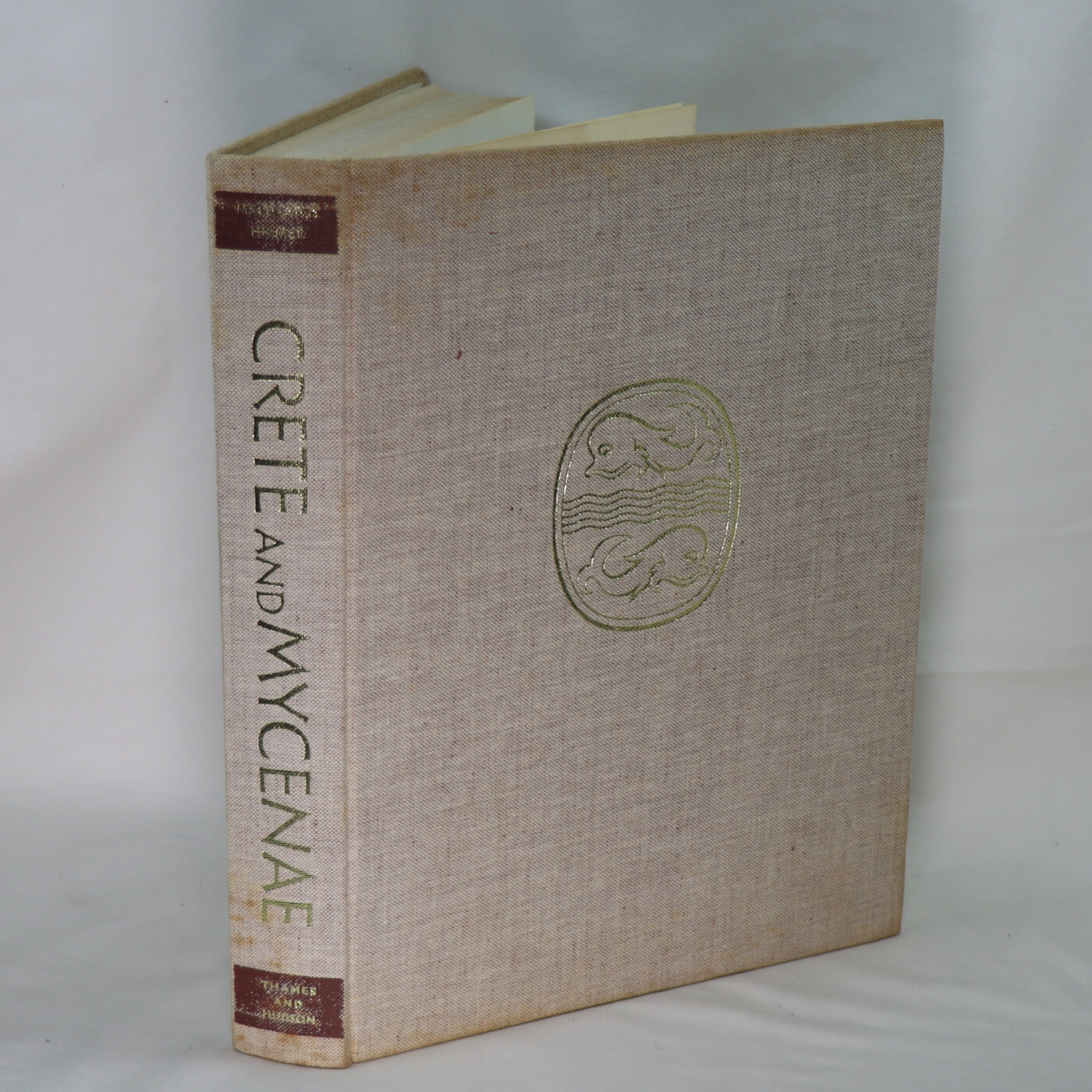

Crete and Mycenae.

Printed: 1960

Publisher: Thames & Hudson. London

| Dimensions | 25 × 31 × 4 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 25 x 31 x 4

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

Cream cloth binding with gilt title on the spine. and gilt dolphins on the front board.

-

We provide an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

-

Note: This book carries a £5.00 discount to those that subscribe to the F.B.A. mailing list.

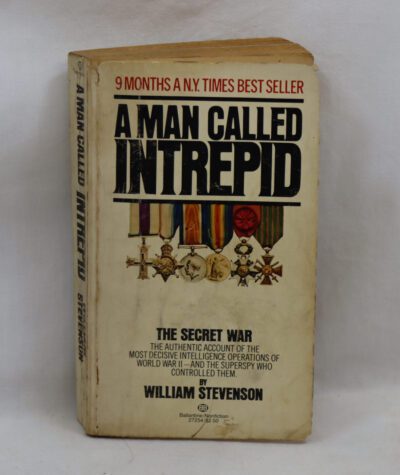

First Edition: Superbly produced art book with scholarly text and excellent illustrations. 176 paginated pages of text ; 52 colour plates, 236 monochrome plates, 28 text figures. Lacks Dust Jacket.

Review: This is an excellent review of the arts and history of Minoan and Mycenaean Crete. The full color art is pasted within the text.

Spyridon Marinatos (17 November [O.S. 4 November] 1901 – 1 October 1974) was a Greek archaeologist who specialised in the Bronze Age Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. He is best known for the excavation of the Minoan site of Akrotiri on Santorini, which he conducted between 1967 and 1974. A recipient of several honours in Greece and abroad, he was considered one of the most important Greek archaeologists of his day.

A native of Kefalonia, Marinatos was educated at the University of Athens, at the Humboldt University of Berlin and at the University of Halle. His early teachers included noted archaeologists such as Panagiotis Kavvadias, Christos Tsountas and Georg Karo. He joined the Greek Archaeological Service in 1919, and spent much of his early career on the island of Crete, where he excavated several Minoan sites, served as director of the Heraklion Museum, and formulated his theory that the collapse of Neopalatial Minoan society had been the result of the eruption of the volcanic island of Santorini around 1600 BCE.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Marinatos surveyed and excavated widely in the region of Messenia in southwest Greece, collaborating with Carl Blegen, who was engaged in the simultaneous excavation of the Palace of Nestor at Pylos. He also discovered and excavated the battlefield of Thermopylae and the Mycenaean cemeteries at Tsepi and Vranas [el] near Marathon in Attica.

Marinatos served three times as head of the Greek Archaeological Service, firstly between 1937 and 1939, secondly between 1955 and 1958, and finally under the military junta which ruled Greece between 1967 and 1974. In the late 1930s, he was close to the quasi-fascist dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas, under whom he initiated legislation to restrict the roles of women in Greek archaeology, and he was later an enthusiastic supporter of the junta. His leadership of the Archaeological Service has been criticised for its cronyism and for promoting the pursuit of grand discoveries at the expense of good scholarship. Marinatos died while excavating at Akrotiri in 1974, and is buried at the site.

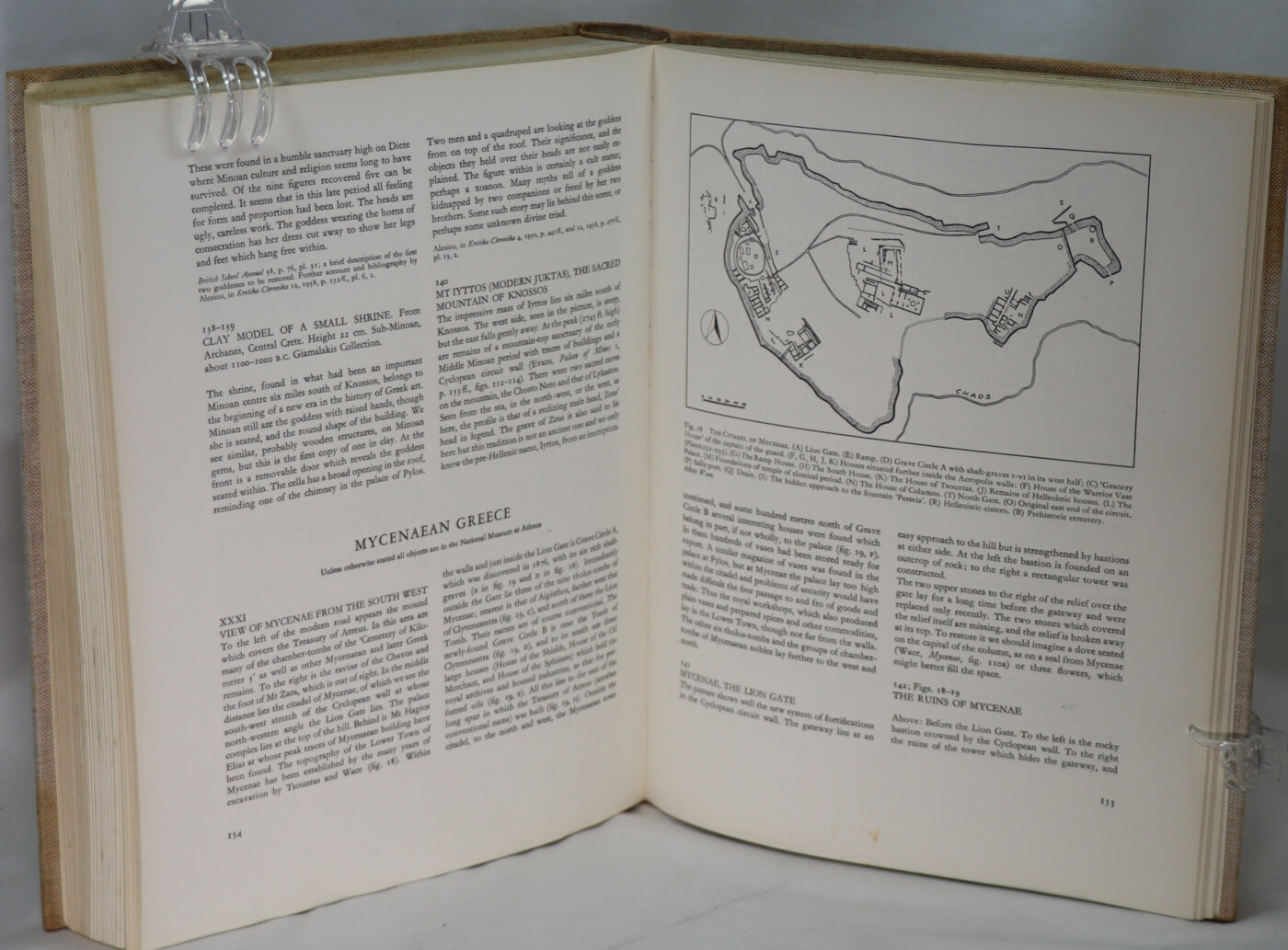

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland Greece with its palatial states, urban organization, works of art, and writing system.The Mycenaeans were mainland Greek peoples who were likely stimulated by their contact with insular Minoan Crete and other Mediterranean cultures to develop a more sophisticated socio political culture of their own.] The most prominent site was Mycenae, after which the culture of this era is named. Other centers of power that emerged included Pylos, Tiryns, and Midea in the Peloponnese, Orchomenos, Thebes, and Athens in Central Greece, and Iolcos in Thessaly. Mycenaean settlements also appeared in Epirus, Macedonia,on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, and on Cyprus, while Mycenaean-influenced settlements appeared in the Levant and Italy.

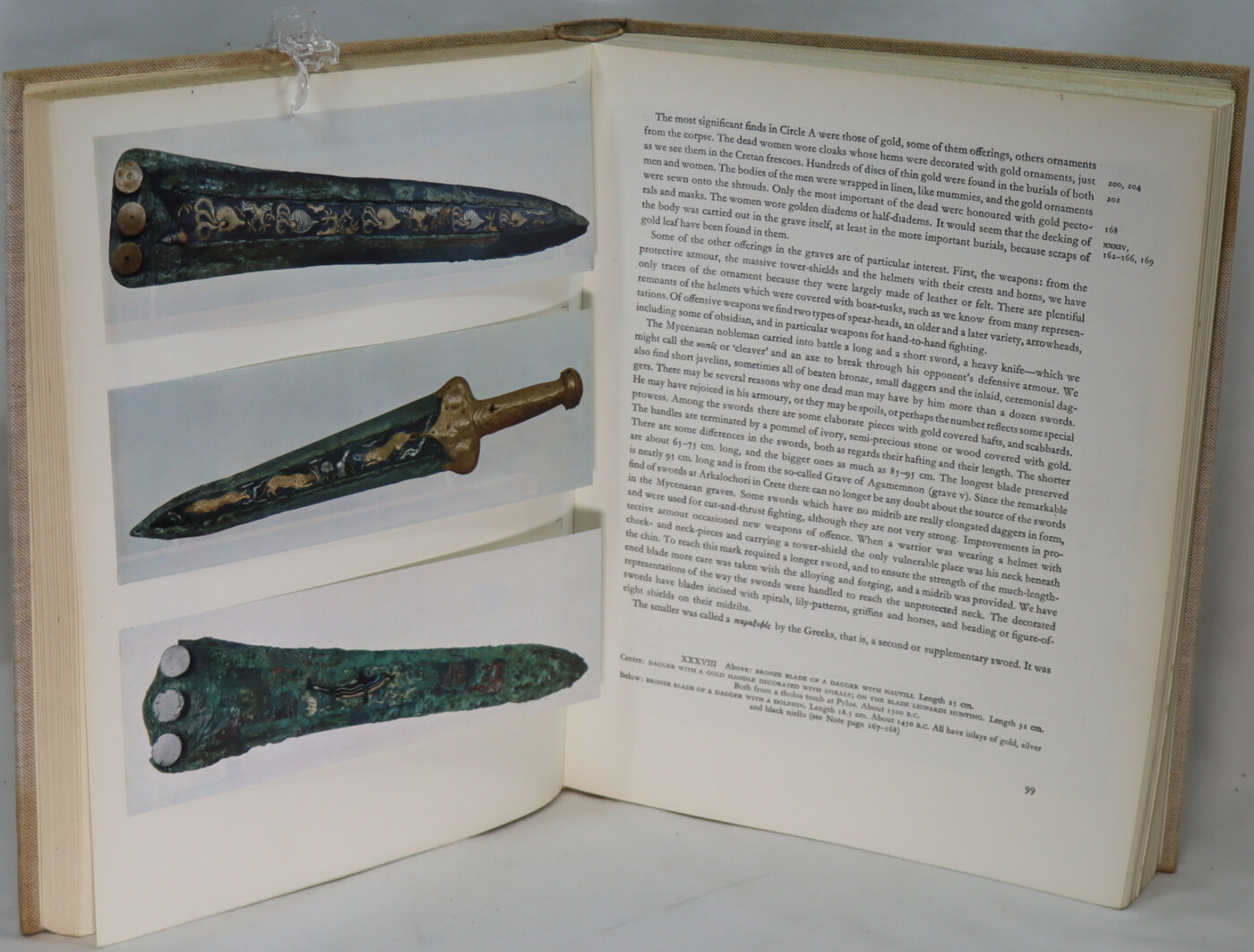

The Mycenaean Greeks introduced several innovations in the fields of engineering, architecture and military infrastructure, while trade over vast areas of the Mediterranean was essential for the Mycenaean economy. Their syllabic script, Linear B, offers the first written records of the Greek language, and their religion already included several deities that can also be found in the Olympic pantheon. Mycenaean Greece was dominated by a warrior elite society and consisted of a network of palace-centered states that developed rigid hierarchical, political, social, and economic systems. At the head of this society was the king, known as a wanax.

Mycenaean Greece perished with the collapse of Bronze Age culture in the eastern Mediterranean, to be followed by the Greek Dark Ages, a recordless transitional period leading to Archaic Greece where significant shifts occurred from palace-centralized to decentralized forms of socio-economic organization (including the extensive use of iron). Various theories have been proposed for the end of this civilization, among them the Dorian invasion or activities connected to the “Sea Peoples”. Additional theories such as natural disasters and climatic changes have also been suggested. The Mycenaean period became the historical setting of much ancient Greek literature and mythology, including the Trojan Epic Cycle.

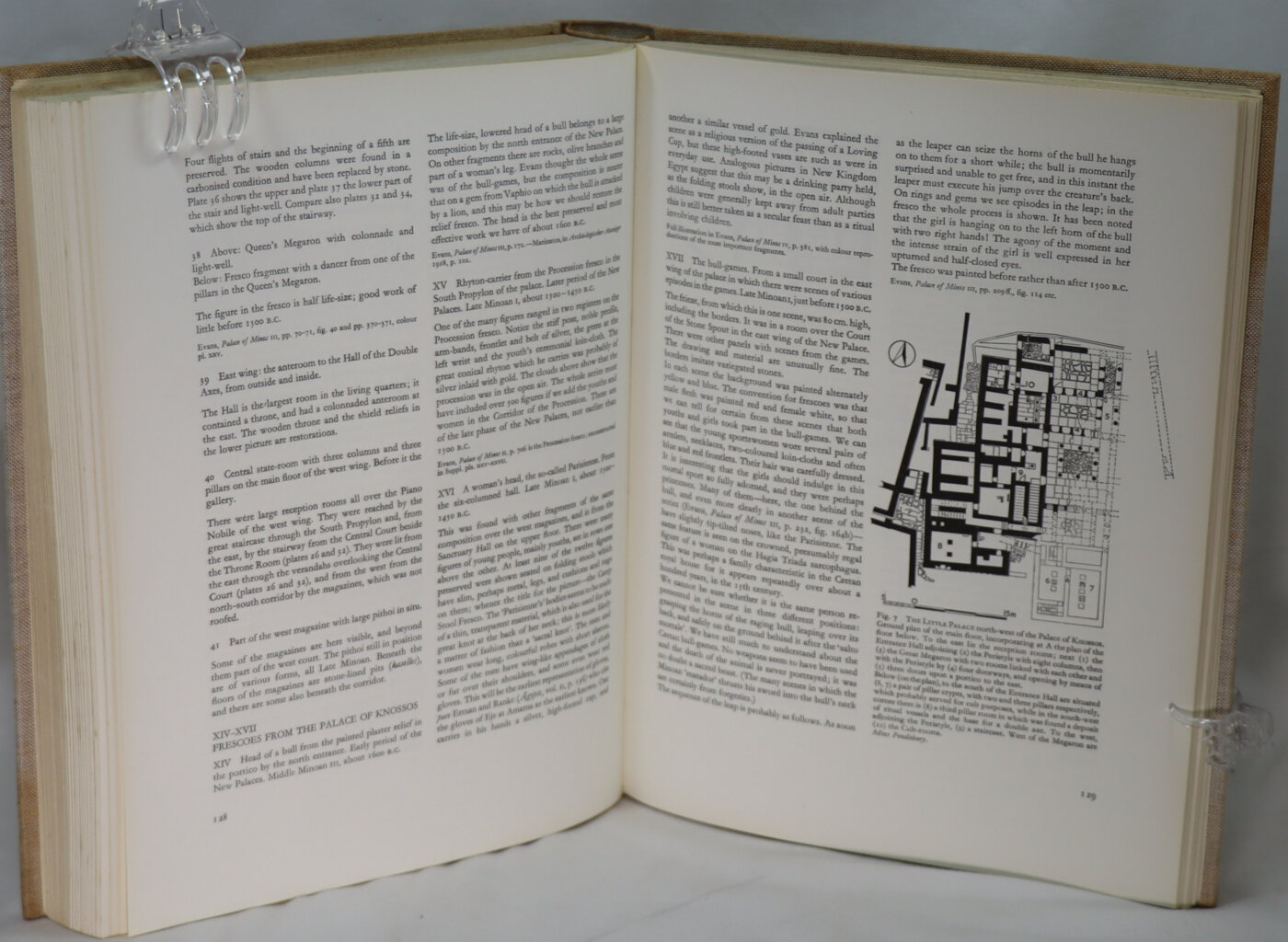

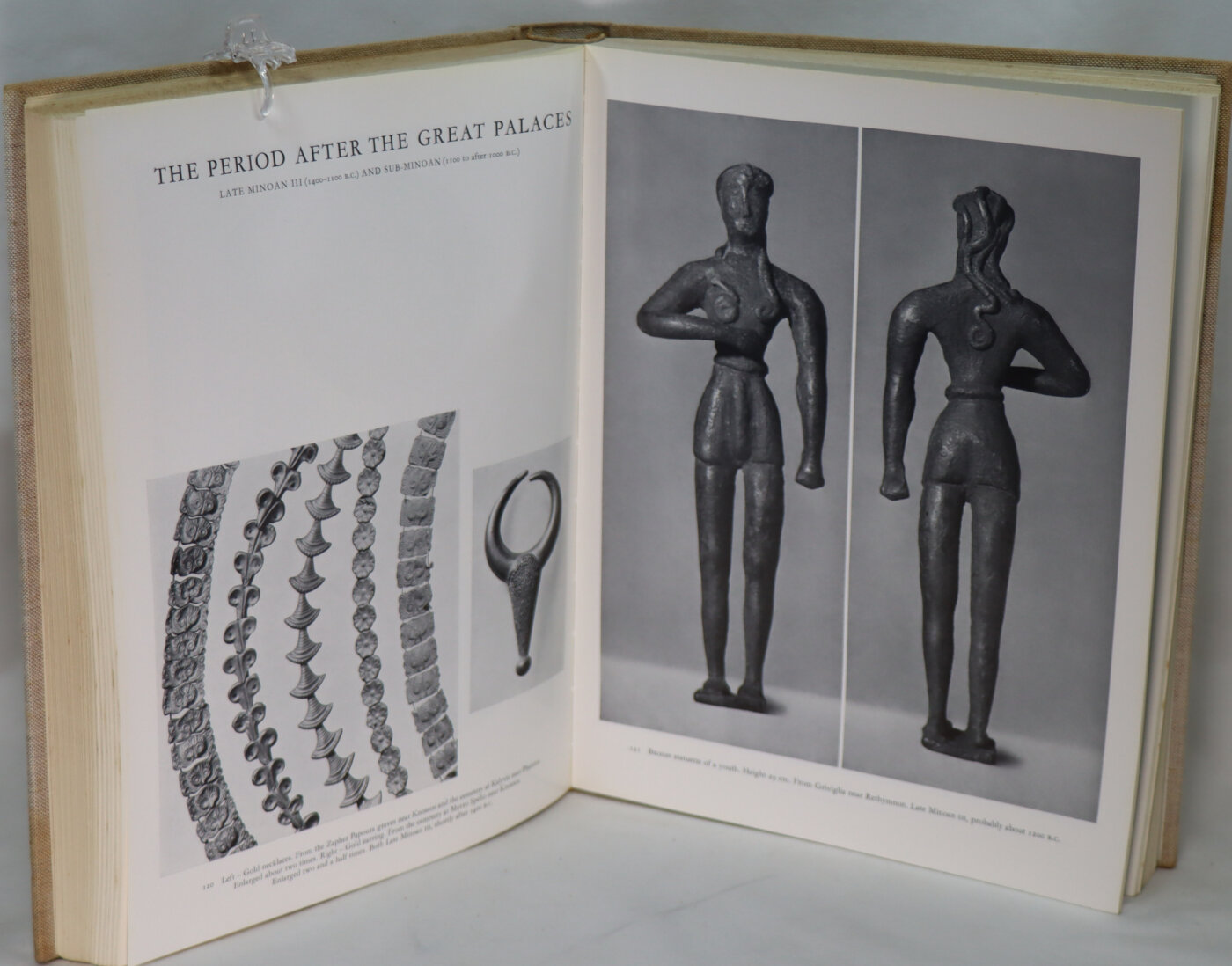

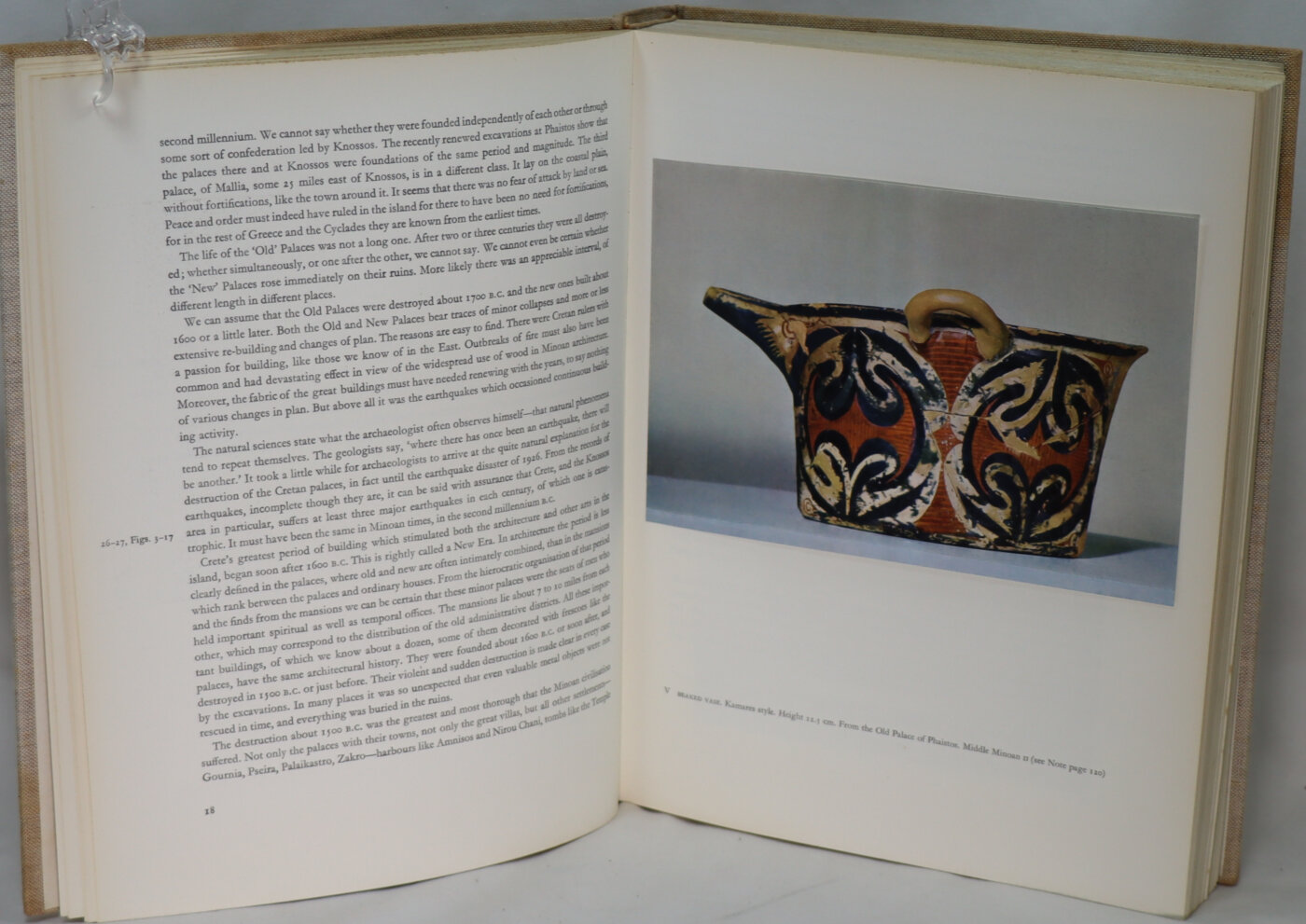

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan palaces at Knossos and Phaistos are popular tourist attractions.

The Minoan civilization developed from the local Neolithic culture around 3100 BC, with complex urban settlements beginning around 2000 BC. After c. 1450 BC, they came under the cultural and perhaps political domination of the mainland Mycenaean Greeks, forming a hybrid culture which lasted until around 1100 BC.

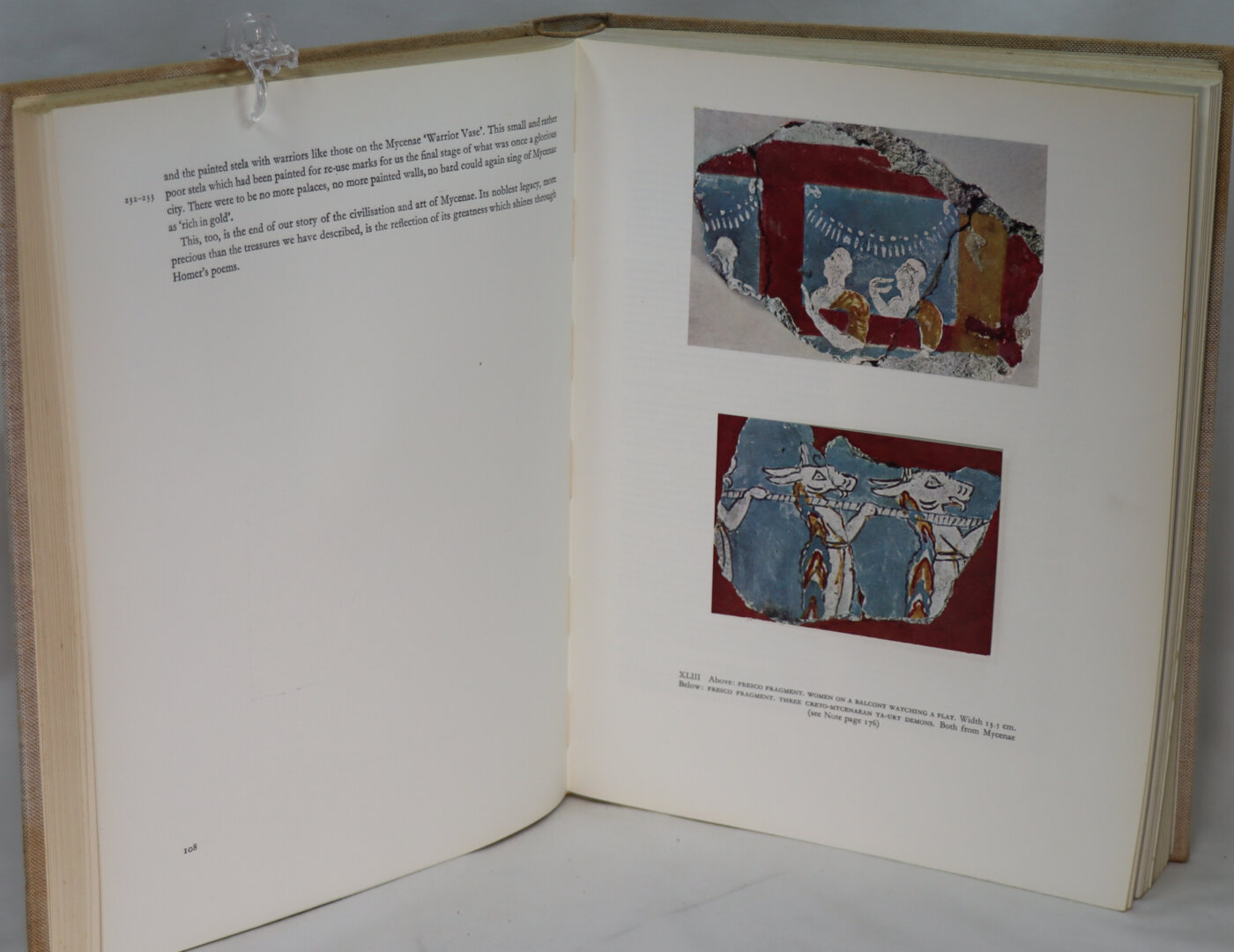

Minoan art included elaborately decorated pottery, seals, figurines, and colorful frescoes. Typical subjects include nature and ritual. Minoan art is often described as having a fantastical or ecstatic quality, with figures rendered in a manner suggesting motion.

Little is known about the structure of Minoan society. Minoan art contains no unambiguous depiction of a monarch, and textual evidence suggests they may have had some other form of governance. Likewise, it is unclear whether there was ever a unified Minoan state. Religious practices included worship at peak sanctuaries and sacred caves, but nothing is certain regarding their pantheon. The Minoans constructed enormous labyrinthine buildings which their initial excavators labeled Minoan palaces. Subsequent research has shown that they served a variety of religious and economic purposes rather than being royal residences, though their exact role in Minoan society is a matter of continuing debate.

The Minoans traded extensively, exporting agricultural products and luxury crafts in exchange for raw metals which were difficult to obtain on Crete. Through traders and artisans, their cultural influence reached beyond Crete to the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. Minoan craftsmen were employed by foreign elites, for instance to paint frescoes at Avaris in Egypt.

The Minoans developed two writing systems known as Cretan hieroglyphs and Linear A. Because neither script has been fully deciphered, the identity of the Minoan language is unknown. Based on what is known, the language is regarded as unlikely to belong to a well-attested language family such as Indo-European or Semitic. After 1450 BC, a modified version of Linear A known as Linear B was used to write Mycenaean Greek, which had become the language of administration on Crete. The Eteocretan language attested in a few post-Bronze Age inscriptions may be a descendant of the Minoan language.

Largely forgotten after the Late Bronze Age collapse, the Minoan civilization was rediscovered in the early twentieth century through archaeological excavation. The term “Minoan” was coined by Arthur Evans, who excavated at Knossos and recognized it as culturally distinct from the mainland Mycenaean culture. Soon after, Federico Halbherr and Luigi Pernier excavated the Palace of Phaistos and the nearby settlement of Hagia Triada. A major breakthrough occurred in 1952, when Michael Ventris deciphered Linear B, drawing on earlier work by Alice Kober. This decipherment unlocked a crucial source of information on the economics and social organization in the final year of the palace. Minoan sites continue to be excavated, recent discoveries including the necropolis at Armeni and the harbour town of Kommos.

Want to know more about this item?

Share this Page with a friend