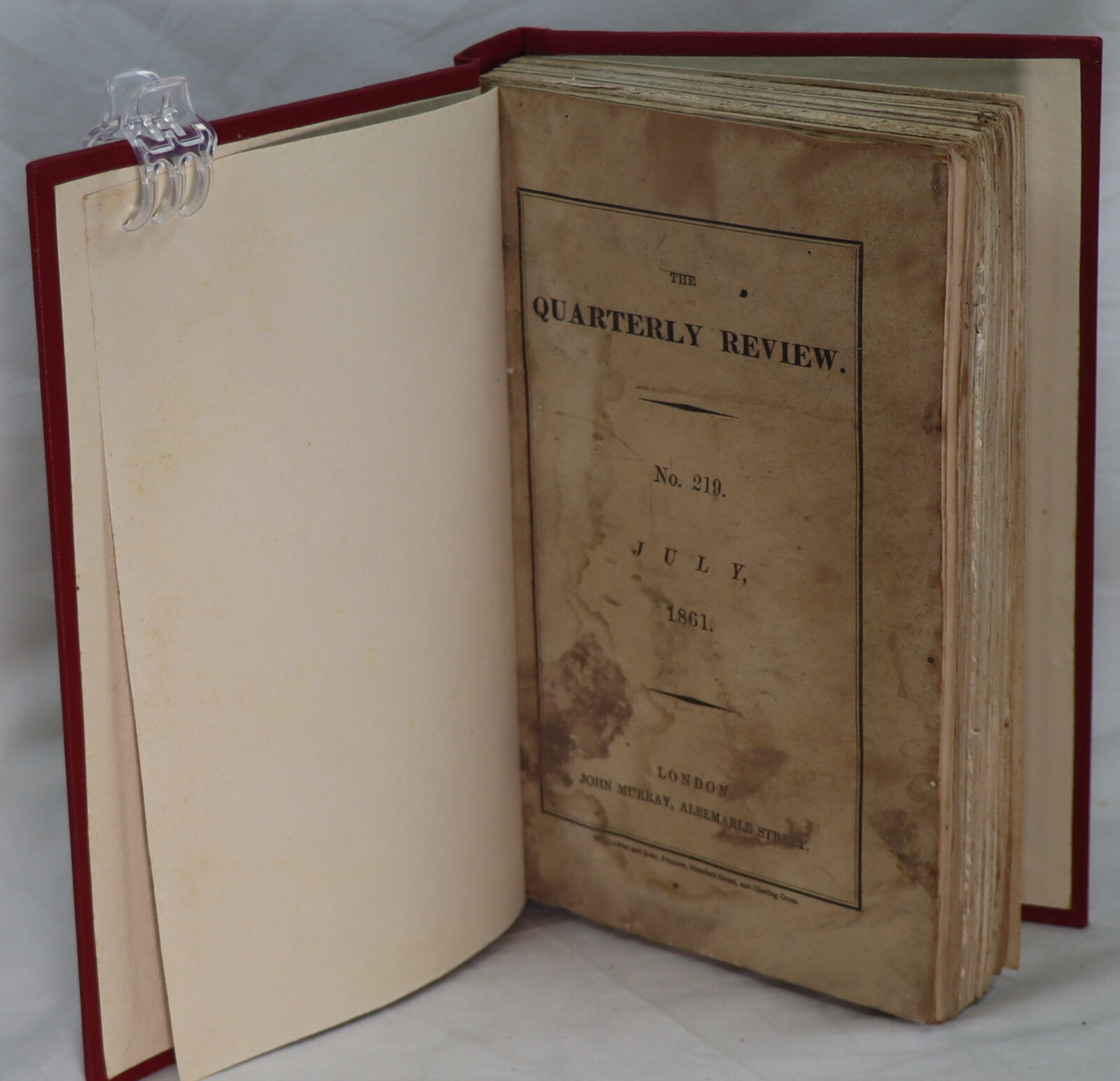

The Quarterly Review. July 1861.

Printed: 1861

Publisher: John Murray. London

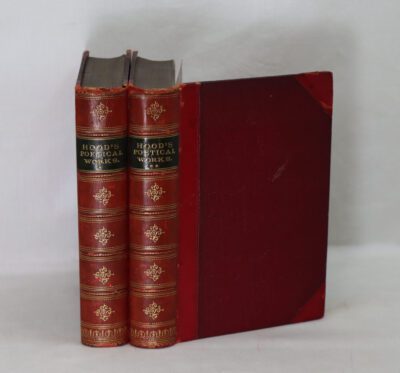

| Dimensions | 15 × 23 × 3 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 15 x 23 x 3

Condition: Very good (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

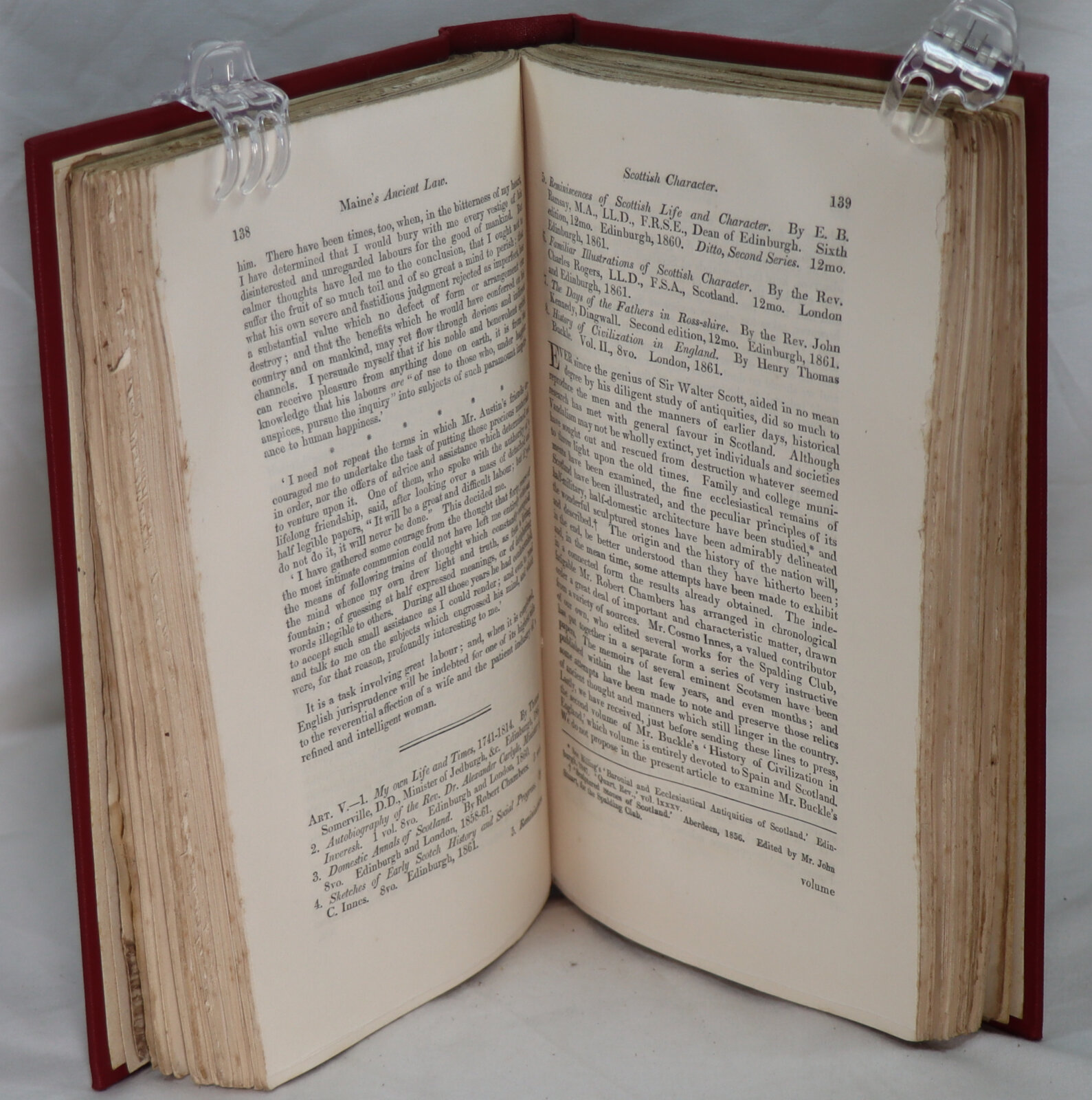

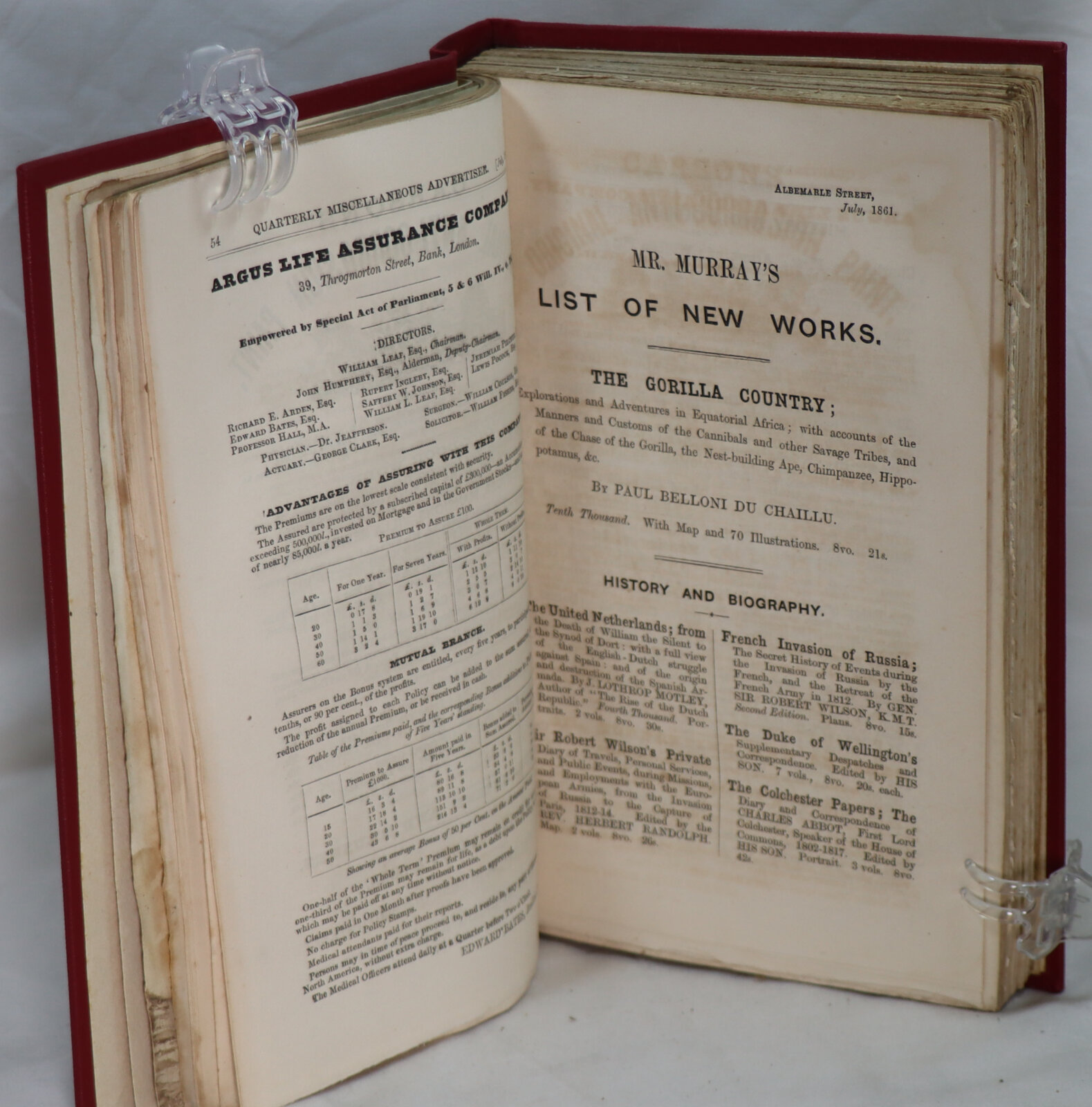

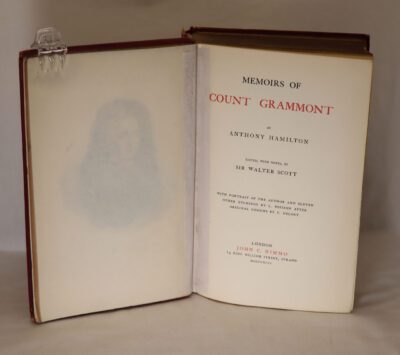

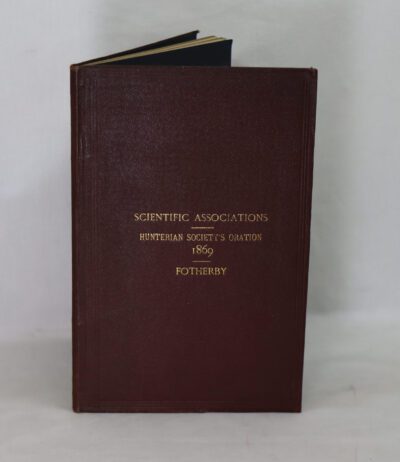

Rebound in red cloth binding with gilt title on the spine.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

This is a rare and well bound edition. The Quarterly Reviews of 1861 are stacked full of historic interest being a gripping and original account of how the US Civil began and a second American revolution unfolded, setting Abraham Lincoln on the path to greatness and millions of slaves on the road to freedom.

The Quarterly Review was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967. It was referred to as The London Quarterly Review, as reprinted by Leonard Scott, for an American edition.

Initially, the Quarterly was set up primarily to counter the influence on public opinion of the Edinburgh Review. Its first editor, William Gifford, was appointed by George Canning, at the time Foreign Secretary, later Prime Minister.

Early contributors included Secretaries of the Admiralty John Wilson Croker and Sir John Barrow, Poet Laureate Robert Southey, poet-novelist Sir Walter Scott, Italian exile Ugo Foscolo, Gothic novelist Charles Robert Maturin, and the essayist Charles Lamb.

Under Gifford, the journal took the Canningite liberal-conservative position on matters of domestic and foreign policy, if only inconsistently. It opposed major political reforms, but it supported the gradual abolition of slavery, moderate law reform, humanitarian treatment of criminals and the insane, and the liberalizing of trade. In a series of articles in its pages, Southey advocated a progressive philosophy of social reform. Because two of his key writers, Scott and Southey, were opposed to Catholic emancipation, Gifford did not permit the journal to take a clear position on that issue.

Reflecting divisions in the Conservative party itself, under its third editor, John Gibson Lockhart, the Quarterly became less consistent in its political philosophy. While Croker continued to represent the Canningites and Peelites, the party’s liberal wing, it also found a place for the more extremely conservative views of Lords Eldon and Wellington.

During its early years, reviews of new works were sometimes remarkably long. That of Henry Koster’s Travels in Brazil (1816) ran to forty-three pages.

Typical of early nineteenth-century journals, reviewing in the Quarterly was highly politicized and on occasion excessively dismissive. Writers and publishers known for their Unitarian or radical views were among the early journal’s main targets. Prominent victims of scathing reviews included Irish novelist Lady Morgan (Sydney Owenson), English poet and essayist Walter Savage Landor, as well as English novelist Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley.

In an 1817 article, John Wilson Croker attacked John Keats in a review of Endymion for his association with Leigh Hunt and the so-called Cockney School of poetry. Shelley blamed Croker’s article for bringing about the death of the seriously ill poet, ‘snuffed out’, in Byron’s ironic phrase, ‘by an article’.

In 1816, Sir Walter Scott reviewed his own, but anonymously published, Tales of My Landlord, partly to deflect suspicion that he was the author; he proved one of the book’s harshest critics. Scott was also the author of a favourable review of Jane Austen’s Emma.

John Murray is a Scottish publisher, known for the authors it has published in its long history including Jane Austen, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Lord Byron, Charles Lyell, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Herman Melville, Edward Whymper, Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo, and Charles Darwin. Since 2004, it has been owned by conglomerate Lagardère under the Hachette UK brand.

The business was founded in London in 1768 by John Murray (1737–1793), an Edinburgh-born Royal Marines officer, who built up a list of authors including Isaac D’Israeli and published the English Review.

John Murray the elder was one of the founding sponsors of the London evening newspaper The Star in 1788.

John Murray II

He was succeeded by his son John Murray II, who made the publishing house important and influential. He was a friend of many leading writers of the day and launched the Quarterly Review in 1809. He was the publisher of Jane Austen, Sir Walter Scott, Washington Irving, George Crabbe, Mary Somerville and many others. His home and office at 50 Albemarle Street in Mayfair was the centre of a literary circle, fostered by Murray’s tradition of “four o’clock friends”, afternoon tea with his writers.

Murray’s most notable author was Lord Byron, who became a close friend and correspondent of his. Murray published many of his major works, paying him over £20,000 in rights. On 10 March 1812 Murray published Byron’s second book, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, which sold out in five days, leading to Byron’s observation “I awoke one morning and found myself famous”.

On 17 May 1824 Murray participated in one of the most notorious acts in the annals of literature. Byron had given him the manuscript of his personal memoirs to publish later on. Together with five of Byron’s friends and executors, he decided to destroy Byron’s manuscripts because he thought the scandalous details would damage Byron’s reputation. With only Thomas Moore objecting, the two volumes of memoirs were dismembered and burnt in the fireplace at Murray’s office. It remains unknown what they contained.

John Murray III

John Murray III (1808–1892) continued the business and published Charles Eastlake’s first English translation of Goethe’s Theory of Colours (1840), David Livingstone’s Missionary Travels (1857), and Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859). Murray III contracted with Herman Melville to publish Melville’s first two books, Typee (1846) and Omoo (1847) in England; both books were presented as nonfiction travel narratives in Murray’s Home and Colonial Library series, alongside such works as the 1845 second edition of Darwin’s Journal of Researches from his travels on HMS Beagle. John Murray III also started the Murray Handbooks in 1836, a series of travel guides from which modern-day guides are directly descended. The rights to these guides were sold around 1900 and subsequently acquired in 1915 by the Blue Guides.

John Murray IV

His successor Sir John Murray IV (1851–1928) was publisher to Queen Victoria. Among other works, he published Murray’s Magazine from 1887 until 1891. From 1904 he published the Wisdom of the East book series. Competitor Smith, Elder & Co. was acquired in 1917.

His son Sir John Murray V (1884–1967), grandson John Murray VI (John Arnaud Robin Grey Murray, known as Jock Murray; 1909–1993) and great-grandson John Murray VII (John Richmond Grey Murray; 1941–) continued the business until it was taken over.

In 2002, John Murray was acquired by Hodder Headline, which was itself acquired in 2004 by the French conglomerate Lagardère Group. Since then, it has been an imprint under Lagardère brand Hachette UK.

In 2015, business publisher Nicholas Brealey became an imprint of John Murray.

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (“the North”) and the Confederacy (“the South”), which had been formed by states that had seceded from the Union. The central cause of the war was the dispute over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prevented from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

Decades of political controversy over slavery were brought to a head by the victory in the 1860 U.S. presidential election of Abraham Lincoln, who opposed slavery’s expansion into the western territories. Seven southern slave states responded to Lincoln’s victory by seceding from the United States and forming the Confederacy. The Confederacy seized U.S. forts and other federal assets within their borders. Four more southern states seceded after the war began and, led by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy asserted control over about a third of the U.S. population in eleven states. Four years of intense combat, mostly in the South, ensued.

During 1861–1862 in the Western Theater, the Union made significant permanent gains—though in the Eastern Theater the conflict was inconclusive. The abolition of slavery became a Union war goal on January 1, 1863, when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared all slaves in rebel states to be free, which applied to more than 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country. To the west, the Union first destroyed the Confederacy’s river navy by the summer of 1862, then much of its western armies, and later seized New Orleans. The successful 1863 Union siege of Vicksburg split the Confederacy in two at the Mississippi River. In 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s incursion north ended at the Battle of Gettysburg. Western successes led to General Ulysses S. Grant’s command of all Union armies in 1864. Inflicting an ever-tightening naval blockade of Confederate ports, the Union marshaled resources and manpower to attack the Confederacy from all directions. This led to the fall of Atlanta in 1864 to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, followed by his March to the Sea. The last significant battles raged around the ten-month Siege of Petersburg, gateway to the Confederate capital of Richmond. The Confederates abandoned Richmond, and on April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant following the Battle of Appomattox Court House, setting in motion the end of the war. Lincoln lived to see this victory but on April 14, he was assassinated.

While the conclusion of the American Civil War arguably has several different dates, Appomattox is often referred to symbolically. It set off a wave of Confederate surrenders. On May 26, the last military department of the Confederacy, the Department of the Trans-Mississippi disbanded. A few small confederate ground forces continued formal surrenders through June 23. By the end of the war, much of the South’s infrastructure was destroyed. The Confederacy collapsed, slavery was abolished, and four million enslaved black people were freed. The war-torn nation then entered the Reconstruction era in an attempt to rebuild the country, bring the former Confederate states back into the United States, and grant civil rights to freed slaves.

The Civil War is one of the most extensively studied and written about episodes in U.S. history. It remains the subject of cultural and historiographical debate. Of particular interest is the persisting myth of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. The American Civil War was among the first wars to use industrial warfare. Railroads, the telegraph, steamships, the ironclad warship, and mass-produced weapons were all widely used during the war. In total, the war left between 620,000 and 750,000 soldiers dead, along with an undetermined number of civilian casualties, making the Civil War the deadliest military conflict in American history. The technology and brutality of the Civil War foreshadowed the coming World Wars.

Condition notes

Want to know more about this item?

Related products

Share this Page with a friend