Granada.

By Walter Jensen

ISBN: 1858217237

Printed: 1999

Publisher: The Pentland Press. Durham

| Dimensions | 16 × 24 × 2 cm |

|---|---|

| Language |

Language: English

Size (cminches): 16 x 24 x 2

Condition: Fine (See explanation of ratings)

Item information

Description

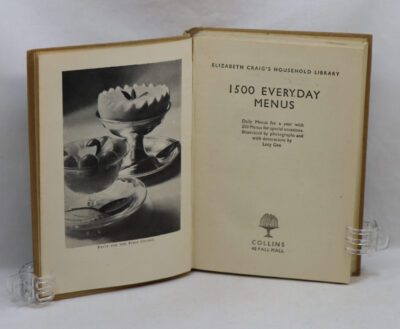

In the original dustsheet. Black cloth binding with gilt title on the spine.

-

F.B.A. provides an in-depth photographic presentation of this item to stimulate your feeling and touch. More traditional book descriptions are immediately available.

An interesting book on a topic little known to Anglos-Saxon audiences.

On 2 January 1492, the last Muslim ruler in Iberia, Emir Muhammad XII, known as “Boabdil” to the Spanish, surrendered complete control of the Emirate of Granada to the Catholic Monarchs (Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile), after the last episode of the Granada War.

The 1492 capitulation of the Kingdom of Granada to the Catholic Monarchs is one of the most significant events in Granada’s history. It brought the demise of the last Muslim-controlled polity in the Iberian Peninsula. The terms of the surrender, outlined in the Treaty of Granada at the end of 1491, explicitly allowed the Muslim inhabitants, known as mudéjares, to continue unmolested in the practice of their faith and customs. This had been a traditional practice during Castilian (and Aragonese) conquests of Muslim cities since the takeover of Toledo in the 11th century. The terms of the surrender pressured Jewish inhabitants to convert or leave within three years, but this provision was quickly superseded by the Alhambra Decree, issued only a few months later on March 31, which instead forced all Jews in Spain to convert or be expelled within four months. Those who converted became known as conversos (converts). This move, along with the progressive erosion of other guarantees provided by the surrender treaty, raised tensions and fears within the remaining Muslim community during the 1490s. Many of the city’s affluent Muslims and its traditional ruling classes emigrated to North Africa in the early years after the conquest, but these early emigrants numbered only a few thousand, with the rest of the population unable to afford leaving.

By 1499, Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros grew frustrated with the slow pace of the efforts of the first archbishop of Granada, Hernando de Talavera, to convert non-Christians and undertook a program of forced baptisms, creating the converso class for Muslims and Jews. Cisneros’s new strategy, which was a direct violation of the terms of the treaty, provoked the Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1499–1501) centered in the rural Alpujarras region southeast of the city. The rebellion lasted until 1500 in Granada and continued until 1501 in the Alpujarras. Responding to the rebellion of 1501, the Crown of Castile rescinded the Treaty of Granada, and mandated that Granada’s Muslims convert or emigrate. Many of the remaining Muslim elites subsequently emigrated to North Africa. The majority of the Granada’s mudéjares converted (becoming the so-called moriscos or Moorish) so that they could stay. Both populations of converts were subject to persecution, execution, or exile, and each had cells that practiced their original religion in secrecy (the so-called marranos in the case of the conversos accused of the charge of crypto-Judaism).

16th-century view of the city, as depicted in Georg Braun’s Civitates orbis terrarum

Over the course of the 16th century, Granada took on an ever more Catholic and Castilian character, as immigrants arrived from other regions of Castile, lured by the promise of economic opportunities in the newly conquered city. At the time of the city’s surrender in 1492 it had a population of 50,000 which included only a handful of Christians (mostly captives), but by 1561 (the year of the first royal census of the city) the population was composed of over 30,000 Christian immigrants and approximately 15,000 moriscos. After 1492 the city’s first churches had been installed in some converted mosques. The vast majority of the city’s remaining mosques were subsequently converted into churches during and after the mass conversions of 1500. In 1531, Charles V founded the University of Granada on the site of the former madrasa built by Yusuf I.

Granada’s Town Council did not fully establish until almost nine years after the Castilian conquest, upon the concession of the so-called ‘Constitutive Charter’ of the Ayuntamiento of Granada on 23 September 1500. From then on, the municipal institution became a crucible for the “Old Christian” and the converted morisco elites, resulting in strong factionalism, particularly after 1508. The new period also saw the creation of a number of other new institutions such as the Cathedral Cabildo, the Captaincy–General, the Royal Chapel and the Royal Chancellery. For the rest of the 16th century the Granadan ruling oligarchy featured roughly a 40% of (Jewish) conversos and about 31% of hidalgos. From the 1520s onward, the mosque structures themselves began to be replaced with new church buildings, a process which continued for most of the century. In December 1568, during a period of renewed persecution against moriscos, the Second Morisco Rebellion broke out in the Alpujarras. Although the city’s morisco population played little role in the rebellion, King Philip II ordered the expulsion of the vast majority of the morisco population from the Kingdom of Granada, with the exception of those artisans and professionals judged essential to the economy. The expelled population was redistributed to other cities throughout the Crown of Castile. The final expulsion of all moriscos from Castile and Aragon was carried out between 1609 and 1614.

Want to know more about this item?

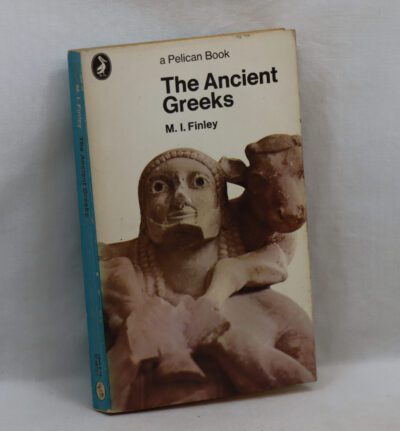

Related products

Share this Page with a friend